We accessioned a small book illustration last week that has an interesting, although slightly embarrassing story associated with it—at least for the inept pile of sailors that were involved in the incident!

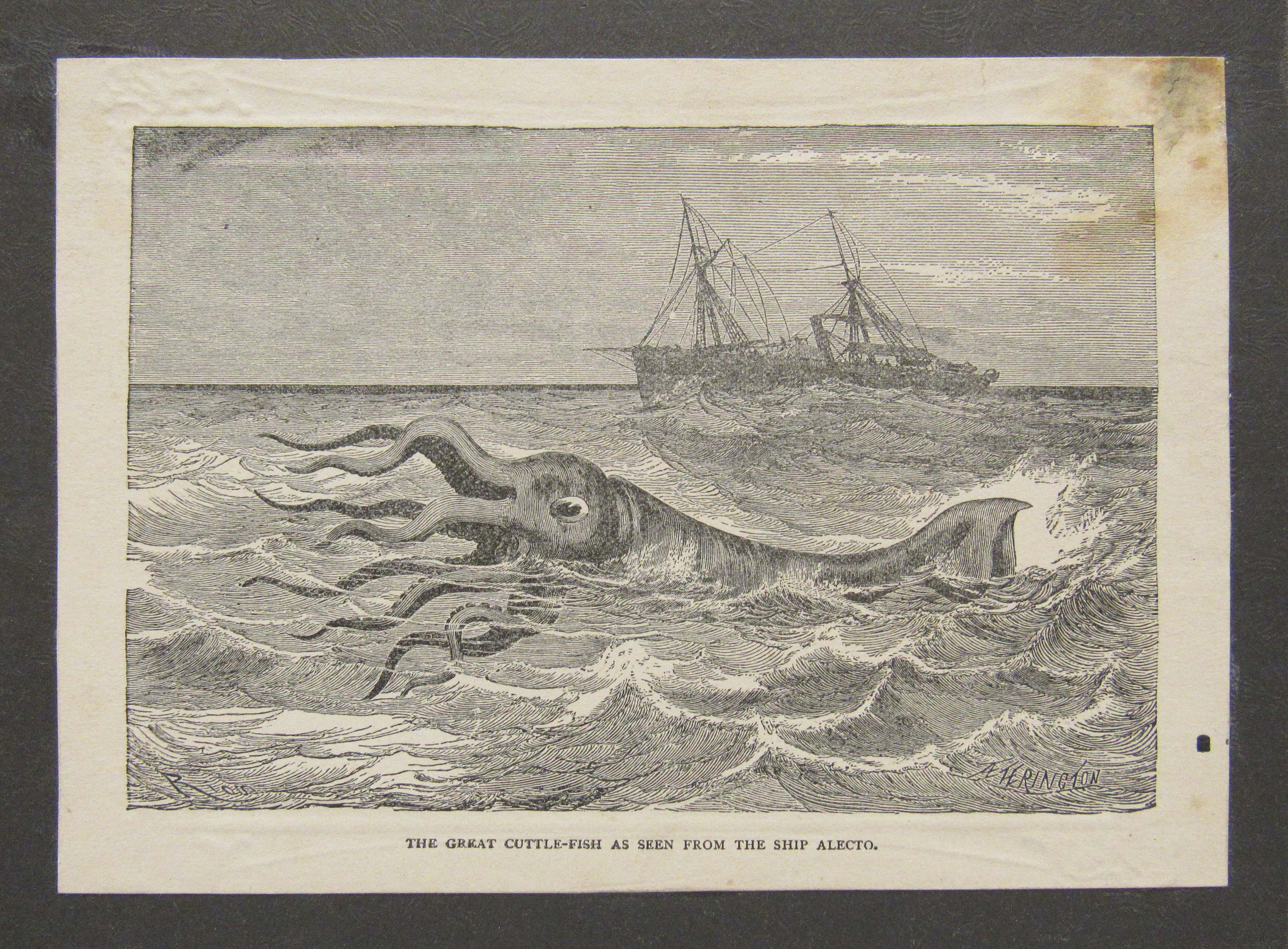

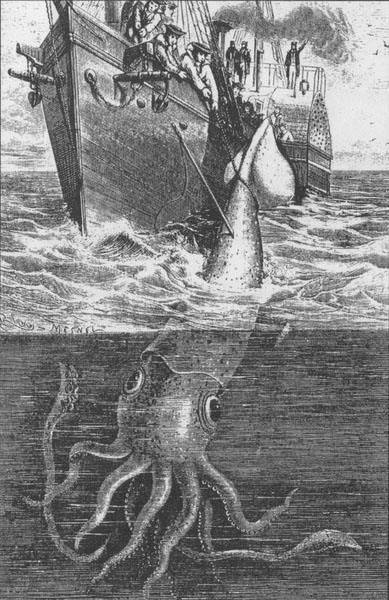

The print came from the 1887 book “Sea and Land: An Illustrated History of The Wonderful and Curious Things of Nature Existing before and since the Deluge…” by James W. Buel. It’s titled “The Great Cuttle-Fish as Seen from the Ship Alecto.” For those of you who don’t know what a cuttlefish is, it’s a cephalopod which is the family of marine animals that includes squids and octopi.

The ship involved in the incident was actually named Alecton. It was a corvette with sidewheels built for the French Navy (here’s your first clue that something isn’t going to go well—my apologies to France and all my French Facebook friends–I’m an unapologetic Horatio Nelson fan). At any rate, while navigating in the Canary Islands near Tenerife in November 1861, Alecton’s lookout reported seeing a large body floating on the surface of the ocean. Curious, the ship’s commander, Lieutenant Frédéric-Marie Bouyer, decided to investigate. What Alecton had stumbled across was a rarely seen giant squid (their normal hang out is about 3,000 feet deep). It was described as “brick red” in color and about 36 to 40 feet long with an estimated weight of two tons. Its eyes were “prodigiously developed” (read: BIG) “and glared with frightful fixity” (read: these big, giant eyeballs followed us everywhere we went and it freaked us out).

At the time of the sighting, the very existence of the giant squid was still disputed even though whalers were continually reporting finding the remains of very large squid in the stomachs of the sperm whales they captured. There were also numerous stories of their remains washing up on beaches worldwide. Bouyer, who, amazingly, was aware of this debate, saw this as an opportunity to finally settle the question of the giant squid’s existence once and for all by trying capture the creature.

SO, if you are on a warship and want to capture a huge squishy animal how would YOU do it? Try and scoop it up with something like a big fish net or an old sail? NO! You spend three or four hours firing cannonballs and harpoons at it! Now, and I know you will all be astounded by this, but even with all this metal being flung at it, the squid didn’t appear to suffer much injury and apparently wasn’t too worried about it because it casually submerged and resurfaced three or four times during the course of the “interaction.”

As you would expect, however, Alecton’s sailors eventually wounded or scared the poor thing. Buel says “at length it received a blow which seemed to wound it seriously, for it immediately vomited a great quantity of froth and blood mixed with glutinous matter, which diffused a strong odor of musk.” Some researchers think that this may have been the squid finally deciding “okay, this hurts, I need to get out of here” and releasing its ink in an effort to cover its escape.

Unwilling to give up their prize, the Alecton sailors decided to try and lasso the squid. Umm…really? And you know I am going to say it—but admit it, you’re thinking it too—what kind of freaking idiot thinks he can pick up a two-ton, squishy, slimy, animal by picking it up with a single rope??? And what was the result of this endeavor? When Alecton’s sailors tried to haul the squid on board the rope slid right through its body and cut the poor thing in half leaving them without any proof of their encounter.

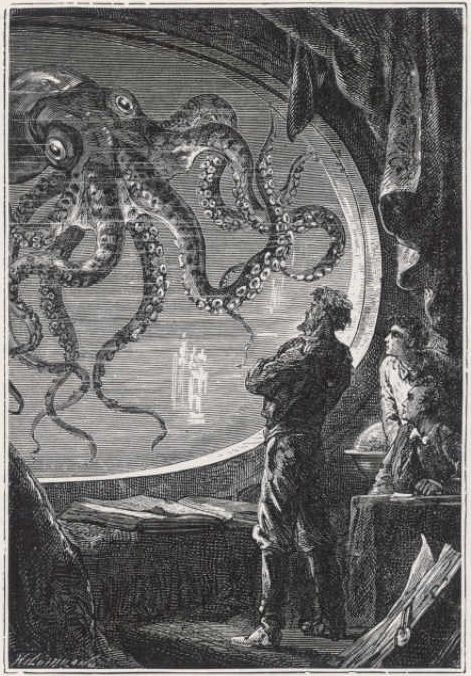

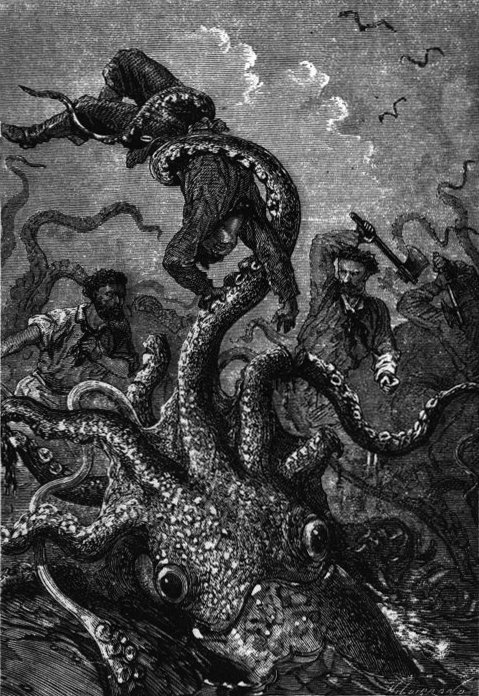

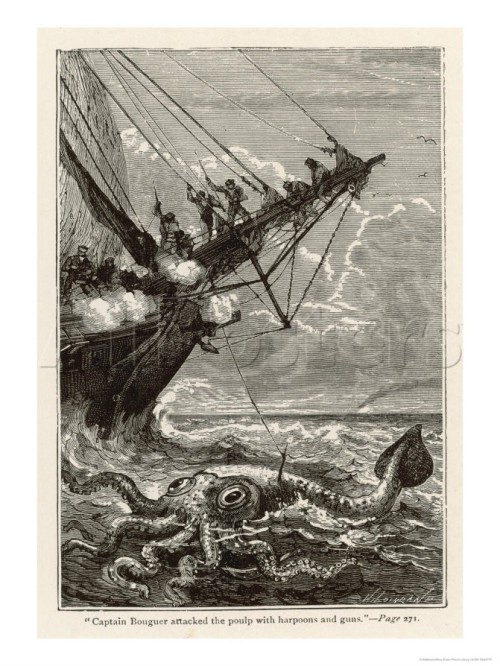

Despite their inability to capture the animal, the sailor’s exciting stories of the encounter inspired Jules Verne to include an attack of a giant octopi on Captain Nemo’s Nautilus in his novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.