Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Russell Mallory immediately recognized the need to construct ironclads to defend the South’s harbors and the Mississippi River watershed. By October 1861, there were five ironclads under construction in New Orleans, Cerro Gordo, Tennessee, and Memphis. It would be an extreme challenge to place these ironclads in the water as effective warships with limited industrial infrastructure. It was all about the questions of time, iron, workers, and engines!

CONTRACT SECURED

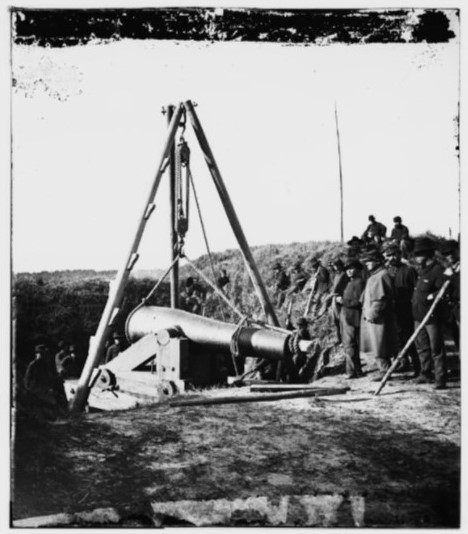

Mathew Brady, photographer. Courtesy of the National Archives Catalog # 528705.

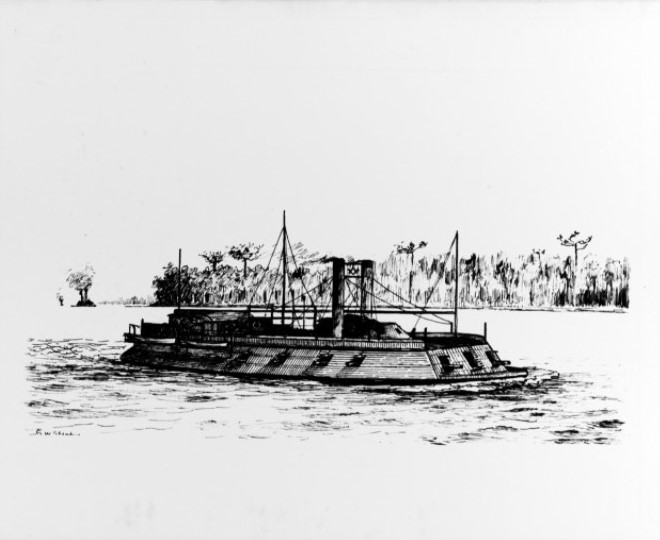

Mallory knew that it was imperative to block the Union gunboats’ ascent down the Mississippi River. As Mallory grappled with starting ironclad construction projects, prominent Memphis riverboat constructor and businessman John T. Shirley traveled to Richmond to meet with Mallory to obtain a contract to build two ironclads at Memphis. These boats were to support Confederate fortifications defending the river. Shirley’s contract entailed building the CSS Arkansas and Tennessee at the cost of $76,920 each. Before leaving Richmond, Shirley consulted with Chief Naval Constructor John Luke Porter to gain knowledge of casemate design. [1]

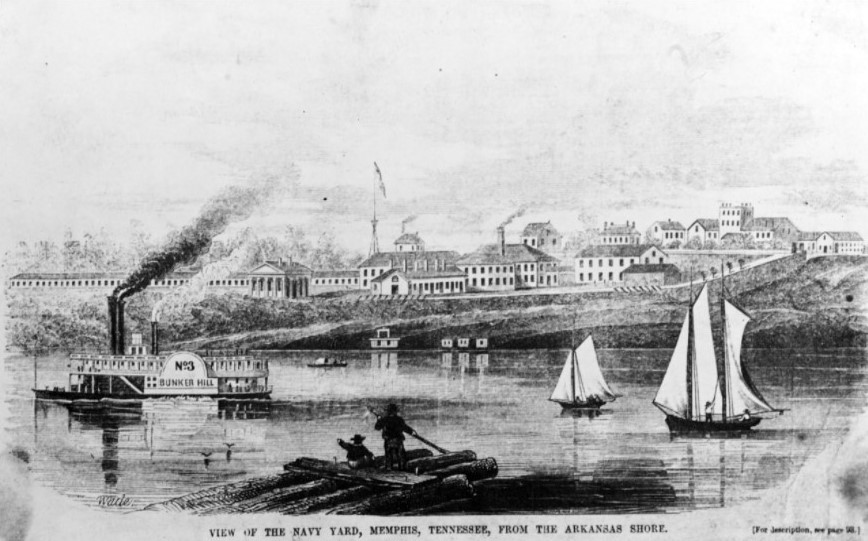

Upon returning to Memphis, Shirley and his master builder Primus Emerson had to find a proper site to build the ironclads. Memphis was once the site of the Memphis Navy Yard. Matthew Fontaine Maury had advocated for its establishment, and the yard was constructed in 1844, producing only one ship. The Memphis Navy Yard was deactivated and sold in 1854.[2]

NEW SHIPYARD

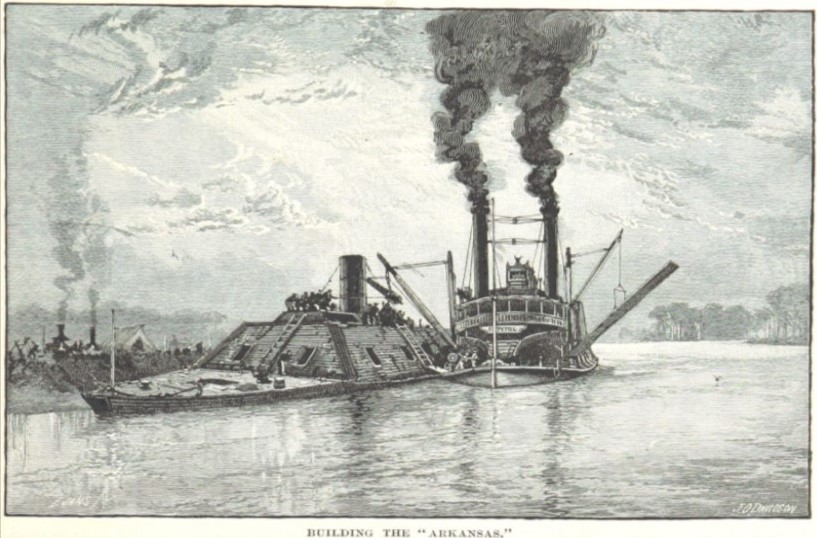

Shirley selected a site near Fort Pickering. This Civil War fort was built atop prior fortifications dating back to the 18th century. The fort was built atop and within Chickasaw burial grounds and mounted 55 guns.[3] The building site was below the bluff upon which the fort was situated. Since Shirley had to build sawmills, drill presses, etc., construction of the two ironclads did not begin until October 1861. Work was delayed by material and labor shortages. The iron plate intended for the Arkansas was delivered instead to Cerro Gordo, Tennessee, the construction site of CSS Eastport. Consequently, Shirley obtained T-rails to armor Arkansas from railroad rails in Memphis and across the river in Arkansas. Bolts were fabricated at the Cumberland Iron Works; yet, they were used by other ships. Shirley, therefore, had to search everywhere to find what he needed. One of his biggest problems was finding manpower to build his ironclads. It was reported that sometimes he had 120 workmen, other times, only 20. [4] The executive officer of Arkansas, Lieutenant Henry K. Stevens, wrote that the “work goes on very slowly, and it seems impossible to get it done any faster.’[5]

SLOW PATH FORWARD

Shirley was supposed to have the two ironclads completed by December 1861; however, Arkansas was half-finished, and Tennessee had just begun. Stevens noted, “she is such a humbug, and badly constructed.”[6] General P.G.T. Beauregard, commander of the Army of the Mississippi, was very concerned about progress on these warships. He knew that he needed ironclads to defend the Mississippi River against Union advances up and down the river. Beauregard was so worried about progress on the Memphis ironclad that he sent his naval aide, Lieutenant John J. Guthrie, to inspect these ironclads and to “remain and overlook their construction….” [7] A few days later Guthrie reported that “one has the keel laid, the ribs and framework in place, and with the present prospect, will not be ready to launch in less than six weeks. The other is further advanced, will soon float…”[8]

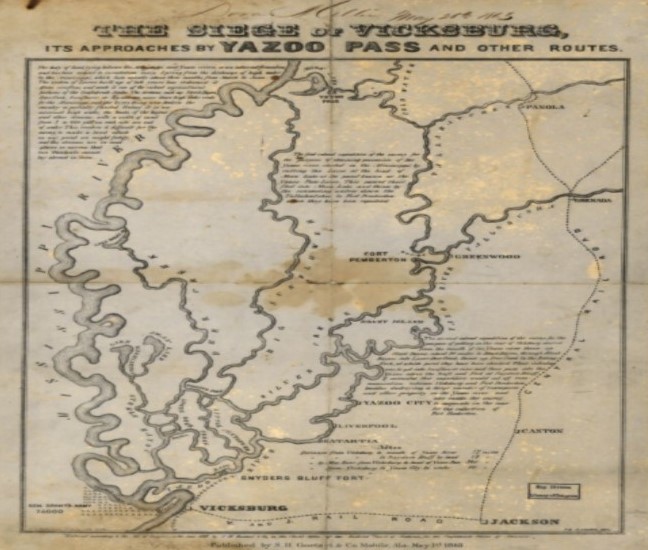

ON TO GREENWOOD

Time was quickly running out for Shirley’s yard. He advised Beauregard that “one of the boats will surely be ready in fifteen days and the other in thirty days…”[9]. The next day, April 26, New Orleans was captured, and Flag Officer David Glasgow Farragut headed his fleet upriver. Furthermore, Flag Officer Charles Henry Davis’s fleet of ironclads and rams were steaming toward Memphis after the capture of Island No. 10. Accordingly, Secretary Mallory named Commander Charles Henry McBlair as commander of the CSS Arkansas. The incomplete CSS Tennessee was burned on the stocks as McBlair commissioned the steamer Capitol to tow the ironclad and a barge filled with machinery, iron bars, guns, etc., up the Yazoo River to Yazoo City. Fears that the Federal fleet might enter that river prompted McBlair to move Arkansas upriver to Greenwood, Mississippi, on May 7, 1862, where the barge sank. Although a diving bell was used to rescue machinery and iron rail from the bottom of the Yazoo River, nothing else was done to finish the ironclad. [10]

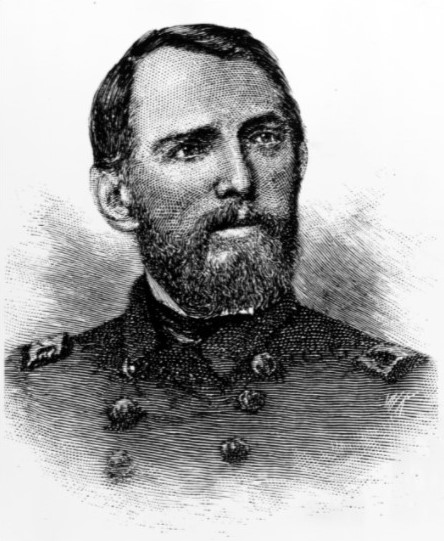

Charles Henry McBlair, a native of Baltimore, Maryland, joined the US Navy in 1823. He commanded the bomb-barge Stromboli during the Mexican War. McBlair also commanded the paddler USS Michigan on the Great Lakes prior to the war. He resigned his commission when he thought that Maryland was leaving the Union. His first assignment was commanding batteries at Fernandina, Florida, until he was detailed to command CSS Arkansas. [11] McBlair was noted for his lethargic leadership, and indeed, work languished on Arkansas while anchored off Greenwood. The town’s citizens telegraphed Mallory, as did General Beauregard complaining about McBlair and wished to have a more energetic officer assigned to the project.

GOODBYE, McBLAIR

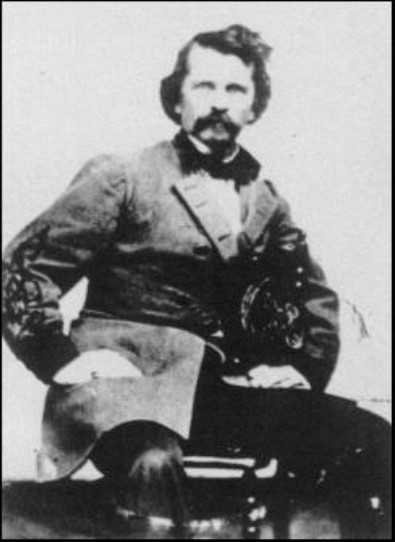

Mallory quickly compiled and detailed Lieutenant Issac Newton Brown to command Arkansas. Lt. Stevens was startled by Brown’s arrival on May 24, 1862, noting, “Today I was astonished to see Lieutenant I.N. Brown come on board and show an order from the Secretary to take command of the Arkansas.” [12] McBlair claimed to have been insulted by Brown, and the former commander returned to Richmond. Brown recounted the incident: “I have had to assume extraordinary powers, both with workmen and officers. The lukewarmness or inefficiency of the commander whom I relieved amounted to practical treason, though he meant nothing of the kind. I have got rid of him, but in doing so I have placed myself inside the mutiny act. I came near shooting him, and must have done so had he not consented and got out of my way.” [13]

NEW ENERGETIC LEADERSHIP

Isaac Newton Brown was from Kentucky and joined the US Navy as a midshipman in March 1834. He fought during the Mexican War. Brown resigned his commission in April 1861. Lieutenant Brown was immediately sent to the Mississippi region. He was given command of CSS Arkansas as he was known to be full of energy and drive. Lieutenant John Grimbell noted in a letter to his father that Brown is “the right man in the right place. He is not afraid of responsibility and there is nothing of the Red Tape about him. [14] He was determined to get the ironclad ready “to strike at the enemies of my country and of mankind. That I will hit them hard when ready…”[15]

When Brown assumed command of Arkansas, the ironclad was a mess. Guns, machinery, supplies, and railroad iron were haphazardly strewn about the ship. Brown quickly moved the warship to Yazoo City as the river was falling. The town was a pre-war cotton port and had steam boat repair facilities available for Brown’s use. There were several insubordinate workers, and Brown had them all arrested and thrown into jail. The lieutenant recruited workers, and 200 soldiers were detached for the project from the local army unit. Plantation owners volunteered their enslaved workmen. Brown also borrowed blacksmith tools and forges from the same plantations to fabricate fittings, bolts, and machinery parts. The men worked 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Lanterns and pine knots were used to light up the night sky. The steamer Capitol was moved alongside Arkansas, and the ship’s hoisting machines were adjusted to power drills for fitting the T-rails. These rails were laid alternatively with crowns up and down. Each rail had six drill holes which were then spiked to the wooden backing. Unfortunately, the rails could not be placed close enough to make a solid surface. [16]

OFFICER CADRE

While Brown would have continuous problems recruiting workers and crew members, Arkansas’s commander secured some of the finest officers in the Confederate navy.

Lieutenant Henry Kennedy Stevens, Executive Officer

Lieutenant George Gift, commander of the bow port 64-pounder Columbiad

Supported by Master’s Mate John Wilson

Lieutenant John Grimball commander bow starboard 64-pounder Columbiad

Supported by Midshipman Dabney Scales

Lieutenant A.D. Warton, commander of starboard broadside guns,

supported by Midshipman R. H. Bacot

Lieutenant Charles W. Read commanded stern 32-pounder rifles

Lieutenant Alphonso Barbot commanded the port broadside guns

Masters John L. Phillips and Samuel Milliken handled the two powder divisions

Surgeon H.W.M. Washington and Assistant Surgeon Charles M. Morfit

Assistant Paymaster Richard Taylor

First Assistant Engineer George Washington City

Second Assistant Engineer E. Covert

Third Assistant Engineers William Jackson, E.H. Brown, James T. Doland, John S. Dupuy, and James S. Gettis

All of these men had difficult duties: the engine system was erratic, gun crews were soldiers in need of training to work heavy naval cannon, and the men willing to be coal heavers and firemen worked in extremely dangerous (red hot!) conditions.

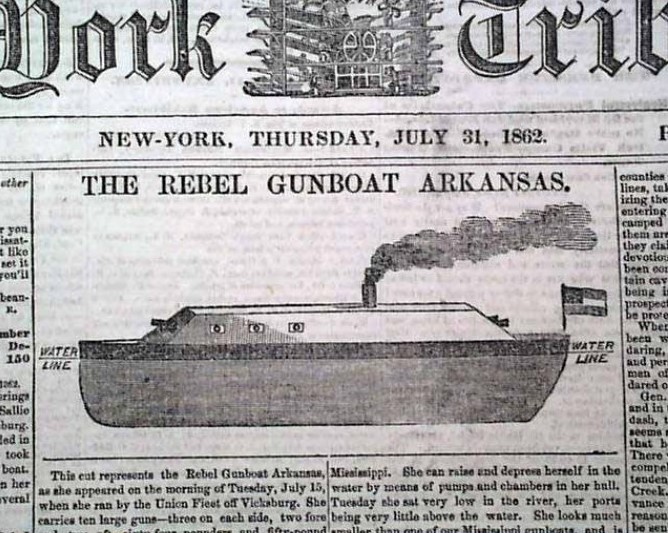

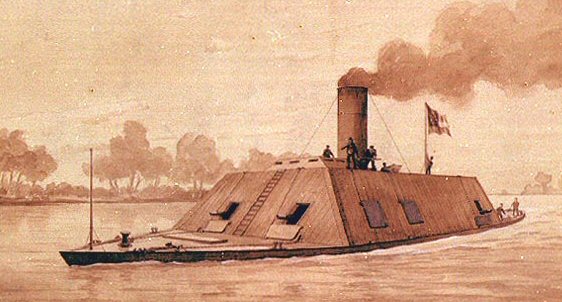

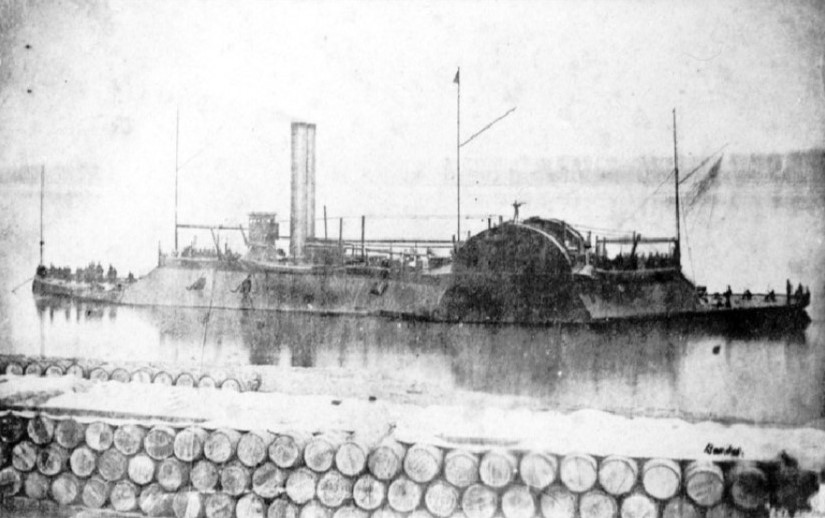

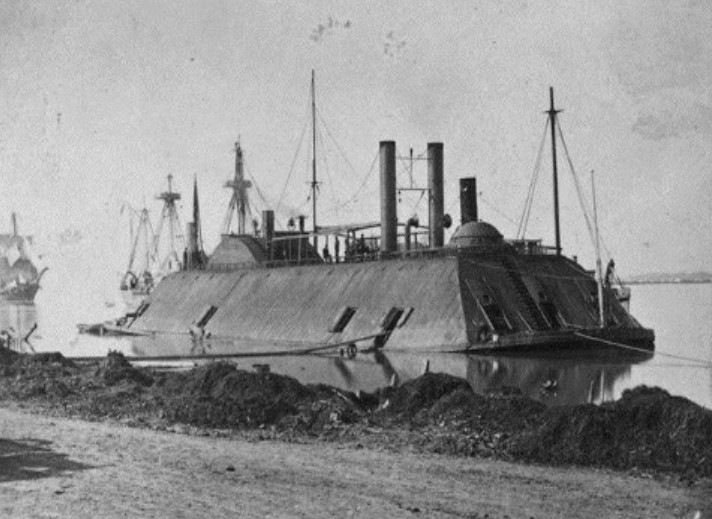

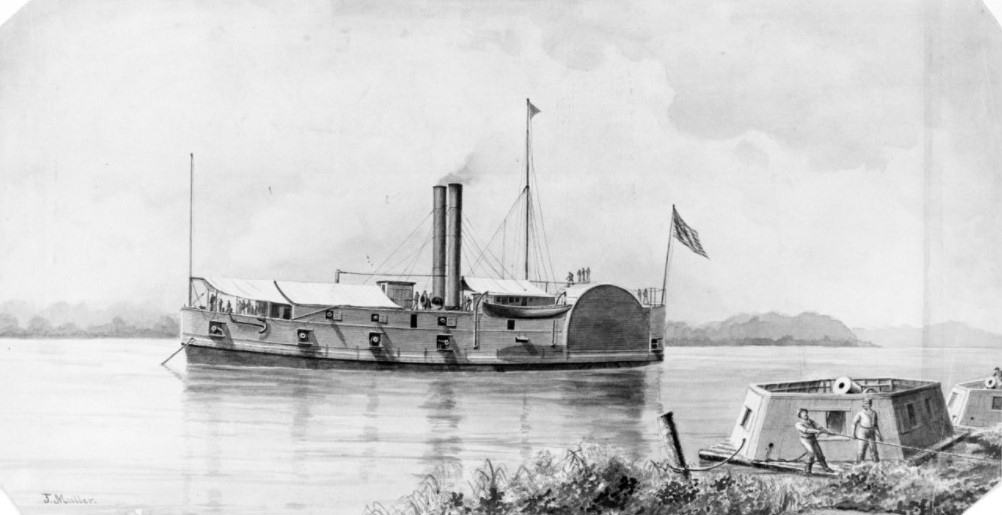

CONSTRUCTING THE IRONCLAD

The Arkansas had a cast-iron ram and carried a battery of ten guns, a modification from the original design. The ironclad was designed with a traditional keeled hull. The casemate had vertical sides with the fore and aft faces sloped at a 35-degree angle. This design feature was to enable Arkansas to steam out into the Gulf of Mexico. The vertical sides of the casemate were built of two feet of oak logs. The shield’s fronts were fabricated of 12-inch oak squares topped by nailed oak planks. The casemate was further backed by a 20-inch-thick pressed cotton backing held in place by wooden planking. Between the gunports, there was a wooden bulkhead. The lack of rolled iron plate made Brown use iron T-rails. These were laid alternately with the crowns up and down. Six drill holes were made to bolt the iron and casemate backing together. The T-rails were not positioned close enough to give them a solid surface.

Furthermore, there was an acute lack of iron to clad Arkansas entirely. The casemate’s stern was covered with one-inch boiler plate for “appearance sake.” The pilot house was built of two layers of one-inch iron bars with small slits that made it difficult for the pilots to see the channel and shoals. The fore and aft decks were unarmored. The broadside gun ports were cut to allow the guns to traverse and were protected by hinged iron shutter. The fore and aft gunports gave the guns little visibility and traverse as they were cut oval. These ports were protected by iron collars from which the guns could protrude.[17]

Just about everything was needed to ready the ship for battle. Only four iron gun carriages came from Memphis. Consequently, Lt. Stevens had to supervise workers in Jackson, Mississippi, to construct carriages for six guns properly. Brown had powder also produced in Jackson, as well as 100 cannonballs forged there. Arkansas’s commander also secured ordnance stores from Lt. David McCorkle’s naval ordnance laboratory in Atlanta.

The engines were installed; however, they were still not operating correctly. The pistons would often hang up and had to be pried into position to start the engines. Workmen toiled rapidly to correct numerous issues. One major problem that was discovered and could not be resolved was that ventilation into the casemate and engine rooms was totally inadequate. To make conditions worse, the boilers were uninsulated. [18]

CSS ARKANSAS CHARACTERISTICS

Displacement: 1,200 tons

Length: 165 ft.

Bean: 35 ft.

Draft: 11 ft, 6 in.

Machinery: 2 screws, 2-low pressure horizontal direct-acting engines, 6 boilers

Speed: 7 knots

Armament: 2 x IX-inch shell guns, 2 x VIII- inch (64-pounder) shell guns, 2 x 32-pounder shell guns, 4 x 32-pounder rifles. [19 ]

FALLING WATERS

Somehow, Brown had achieved the unachievable! After five weeks, the Yazoo River was beginning to fall. Lt. Brown had much arduous work to finish the ironclad; but, the ship had to be moved. Brown descended the Yazoo down to Liverpool Landing. Workmen continued to labor intensively on the gunboat en route to the landing. When Brown reached the landing on June 26, 1862, he witnessed the burning hulks of the ram CSS General Polk and gunboat CSS Livingston. Then news arrived at the landing of Union ships entering the Yazoo River earlier that day. Commander Robert Pinckney panicked and ordered the ships burned. Brown’s men strove to put out the flames; but, it was too late to save the vessels. Fortunately, the warships had already been stripped of their guns, small arms, and materials for Arkansas. Some other supplies had been removed and left along the landing before they were burned. Nevertheless, work continued on the ironclad during its stay at Liverpool Landing to get the ironclad ready for its highly anticipated strike at the Federal fleet. [20]

GENERAL EARL VAN DORN TAKES COMMAND

Major General Earl Van Dorn had recently taken command at Vicksburg. He was an 1841 graduate of West Point. Van Dorn had fought during the Mexican War and fought Comanches in Texas, for which he gained great fame before the Civil War. He joined the Confederate army and was promoted to major general. Nevertheless, his poor logistics and staff work resulted in his defeats at Pea Ridge, Arkansas, and Corinth, Mississippi. Rash and impetuous, he was ill-suited for any command other than that of a cavalry unit.[21]

Nevertheless, Van Dorn was extremely worried about the two Union fleets converging on Vicksburg, commanded by Flag Officer (soon to be promoted rear admiral) David Glasgow Farragut and the other by Flag Officer Charles Henry Davis. So, he wrote President Jefferson Davis requesting operational command of Arkansas, which was quickly given to Van Dorn. He thought Vicksburg so threatened that Van Dorn wrote Brigadier General Daniel Ruggles: ”Can you send a message to the commander of the ram and suggest he come out, run the fleet, and behind them and sink transports…he could clear the river below. It is better to die game and do so execution than to lie by and be burned up the Yazoo.” [22]

Brown was doing everything possible to get Arkansas ready; however, he still needed more men to operate the ironclad. All Van Dorn cared about was how quickly the ironclad could get to Vicksburg and beyond. The general sent orders that Brown’s first objective was to pass the Federal fleet in a daylight passage to reach Vicksburg. There Arkansas would be re-coaled and to clear the river below Vicksburg. Once Brown had accomplished all of this, he was to take his ironclad to Mobile Bay, Alabama.

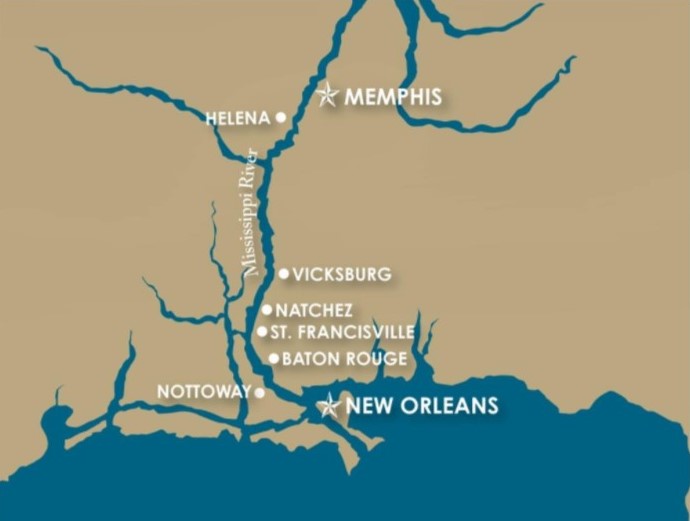

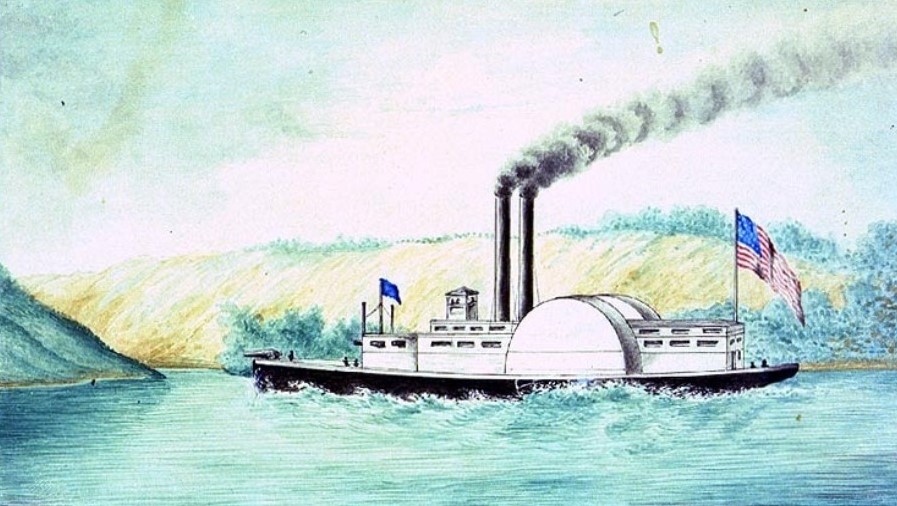

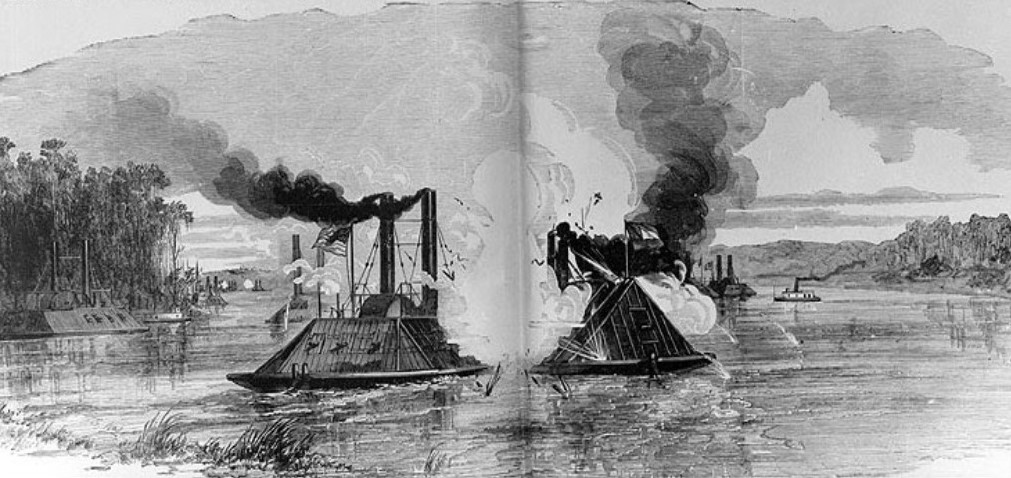

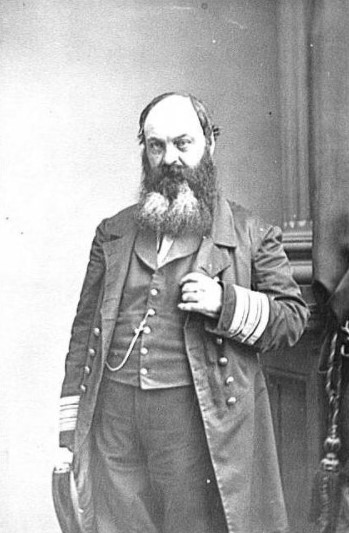

UNION JUGGERNAUT

By June 26, Flag Officer (soon to be promoted to rear admiral on July 16, 1863) David Glasgow Farragut passed the Vicksburg batteries. He joined the Western Gunboat Flotilla commanded by Flag Officer Charles Henry Davis. Farragut had a long naval career, as did Davis. The unified force had overwhelming superiority and controlled most of the river. Davis had the ironclads Benton, Carondelet, Louisville, St. Louis, Essex, Cairo, and rams like Queen of the West and timberclads such as the USS Tyler. Farragut had brought with him from New Orleans ships from the Western Coast Blockading Squadron – the sloops of war Richmond, Hartford, Brooklyn, and the gunboats Itasca, Oneida, Wissahickon, Winona, Sciota, Kennebec, and Katahdin. This was a formidable fleet that Arkansas had to pass before reaching Vicksburg.

Brown remained at Liverpool Landing for two weeks, where he trained recent recruits and crew members of the steamers, finishing outfitting the ironclads and fixing Arkansas’s engines. Once a passage was cut through the raft barrier on July 12, 1862, Brown took his ironclad downriver to Satartia, Mississippi. There he trained his gun crews. Two days later, it was discovered that a steam leak wet the gunpowder in the forward magazine. So, the crew had to take all the gunpowder out of the magazine and lay it on tarps to dry in the sun. Once Arkansas was reloaded with dry powder, Brown steamed his vessel to Hayne’s Bluff, arriving by midnight. The Arkansas’s commander planned to strike the Federals at dawn, anchored in the Mississippi River. [23]

As Arkansas began its strike against the Federal fleet, Brown called his officers together and said: “Gentlemen, in seeking the combat as we must win or perish. Should I fall, whoever succeeds to the command will do so with the resolution to go through the enemy’s fleet, or go to the bottom. Should they carry us by boarding, the Arkansas must be blown up; on no account must she fall into the hands of the enemy. Go to your guns!”[24]

FIRST BLOOD

Both Farragut and Davis had heard rumors of Arkansas being in the Yazoo River. Farragut did not think that the Confederate ironclad would ever be finished. Nevertheless, they agreed that a reconnaissance should be made of the Yazoo by the ram Queen of the West (Lt. Col. Charles R. Ellet), the timberclad Tyler (Lt. Commander William Gwin), and the ironclad Carondelet (Capt. Henry Walke).

The three Union warships were quickly surprised to see the rebel ram approaching at 6:00 a.m. Tyler led the Union ships and was the first to fire, backing down the Yazoo River. The Queen of the West and Carondelet came about. Walke, who had served with Brown before the war, was criticized for this action instead of heading bow first toward Arkansas. He rebutted the complaints about his actions: “Being a stern-wheel boat, the Carondelet required room and time to turn around. To avoid being sunk immediately, she turned and retreated. I was not such a simpleton as to ‘take the bull by the horn,’ to be fatally rammed….If I had continued fighting, bows on, in that narrow river, a collision, which the enemy desired, would have been inevitable, and would have sunk the Carondelet.”[25]

Brown headed his ironclad directly at Carondelet and hoped to ram that ironclad. The Tyler and Queen of the West turned about to support the Union ironclad, and the timberclad drew the first blood of the engagement when a Confederate soldier foolishly poked his head out of a gunport and was decapitated by a shell from Tyler. The Arkansas retaliated by sending a shell into the timberclad’s engine room, killing nine men and wounding 16. The Arkansas’s 64-pounder Columbiad recoiled off its carriage, taking 10 arduous minutes to remount.

Meanwhile, Brown was closing in on Walke’s ironclad and neared to within 50 yards of Carondelet. Shells and shot from Arkansas were penetrating the Union ironclad’s poorly armored stern. Walke ordered his ship to reverse course so that Arkansas could not ram Carondelet. Eight 64-pounder shells had pierced Carondelet’s casemate, and one of the shots had cut the vessel’s steering ropes, forcing the Union ironclad aground. As Arkansas passed Carondelet, a broadside was fired into the stranded Union ship. Brown decided not to continue to bombard Carondelet instead of heading for the Mississippi River. [26]

USS TYLER’S MARKSMANSHIP

The Arkansas was now fighting a running battle with Tyler. The timberclad’s commander, Lt. Commander Gwin, knew his ship was no match for the Confederate ironclad and was in danger of being rammed. The vessel’s stern 30-pounder rifle was executing serious damage despite keeping 200 to 300 yards ahead. One shot hit the casemate knocking Brown unconscious. Another shell smashed through the poorly armored pilothouse, broke off the forward rim of the wheel, and mortally wounded the Yazoo River pilot. Brown, who spent much of the action atop the casemate, had his head grazed by a sharpshooter’s minie ball.

Tyler continued to pump shells onto Arkansas. The smokestack was punctured several times, and shells severed the breechings (the connection between the stack and furnaces). The damaged stack weakened the ironclad’s draft for its boilers. This slowed the ship to about 4 knots which lost Arkansas’s effectiveness as a ram. Temperatures in the engine room rose to 130 degrees, and men working there had to be shifted in and out because of the extreme heat. By this time, Arkansas had suffered 25 casualties. Repairs were made to the breechings as the Confederates entered the sluggish waters of the Mississippi, generating steam by burning oily material. [[27]

TO THE FEDERAL FLEET’S SURPRISE

The fleets of Farragut and Davis were anchored halfway between the mouth of the Yazoo River and Vicksburg. Forty-some warships had their fires banked as they were short on coal, and it lessened the heat that was weakening many of the Union soldiers and sailors. The Union warships were lined up on the Vicksburg side of the river, and all the transports were on the Louisiana side. The warship line began with the ram fleet commanded by Lt. Col. Alfred Ellet, followed by eight gunboats and sloops of war from Flag Officer David Glasgow Farragut’s West Gulf Blockading Squadron, and lastly by Charles Henry Davis’s four ironclads. While this fleet heard cannon firing up the Yazoo River and Davis thought that “most of us came to the conclusion that the firing was upon guerilla parties.”[28] Some ships thought that a fight might be imminent as USS Benton got upstream and Hartfold’s crew began preparing the guns for action – all without orders. [29]

At 7:15 a.m., the Union lookouts saw Queen of the West and Tyler rapidly steaming toward the anchored fleet, followed by Arkansas. Brown, worried about his ship’s speed, decided to keep his ship as close to the anchored Federal men of war as he could. The Arkansas passed the rams without incident; however, when Brown’s ironclad came abreast of Farragut’s wooden warships, they opened fire as they did not wish to miss and then carefully struck the Union transports and hospital ships. The USS Kineo was the first to fire at Arkansas. The cannonade awakened Farragut. He appeared on deck in his nightshirt and “seemed much surprised.” He watched as Arkansas slowly steamed down the Union line. Numerous broadsides were fired at the Confederate ram. While most of them glanced off, three did not. A shell from Hartford broke through the T-rails, a bale of cotton, and 20 inches of wood before exploding inside the casemate. Shell fragments killed four men and wounded several others. Midshipman Dabney Scales vividly reported: “The Captain of the gun standing at my right was knocked down by the concussion and so great was the shock that he lost his mind and never recovered.” [30]

Another shell from USS Iroquois penetrated through the shield that killed or wounded the entire 16-man gun crew of one of the forward Columbiads. Either Winona or Wissahickon sent a solid shot through the casemate near the starboard Dahlgren gun, then it screamed through the boiler exhaust to strike the other side. Through all of the fuselage, Brown was atop the casemate or in the damaged pilothouse.[31]

The Federals also suffered badly from Arkansas’s guns. The USS Lancaster attempted to ram the ironclad. It was stopped dead in the water when a shell from Arkansas pierced Lancaster’s boilers.”Steam poured through the ship as the scalded men jumped overboard, and some of them never came to the surface.” [32].The Arkansas received shot and shell for 30 minutes as the ironclad passed the Union ships. The engagement was fought at a range of 70 to 75 yards, and Arkansas sent shells to every Union ship it went by, seriously damaging USS Pinola.

Many other Union ships also received some type of damage as Arkansas went by them. The USS Benton moved against the Confederate ironclad. Arkansas tried to ram Benton, and the Union vessel was able to navigate out of the way. Nevertheless, Arkansas sent a broadside into Benton, which dissuaded that vessel from following too closely. The USS Cincinnati joined with Benton to follow Arkansas; however, by now, the Confederate ram had reached the protection of the Vicksburg batteries and moored safely at a wharf near the courthouse. [33]

JUBILATION

More than 20,000 Vicksburg citizens and soldiers watched Arkansas steam through the entire Union fleet. People cheered and yelled during the battle; however, the smoke was so thick that all they could see were the gun flashes until Arkansas emerged from the haze. Generals Earl Van Dorn and John Cabell Breckinridge watched the entire engagement from the dome of the courthouse. This was the first victorious Confederate naval duel since the October 17, 1801 Battle of the Passes. The mood turned to an overwhelming stream of accolades. The crowd thronged the wharf, excitedly cheering laudatory cries when they saw the battle’s hero, Lt. Isaac Newton Brown, blood still trickling down his head. The Confederate leadership made much of Arkansas’s heroic achievements.

General Van Dorn said that Brown had “Immortalized his single vessel, himself, and the heroes under his command, by an achievement the most brilliant ever recorded in Naval annals. [34]

The Confederate Congress issued Brown and his men a vote of thanks: “For their single exhibition of skill and gallantry … in a brilliant and successful engagement of the sloop of war Arkansas with the enemy’s fleet.” [35]

Secretary of the Navy Stephen Russell Mallory wrote on August 18, 1862: “I am requested by the President to express, on behalf of the country, whose cause you have nobly sustained, his thanks to yourself, your officers, and crew, for gallant and meritorious conduct you are promoted, and made a commander for the war. [36]

Adjutant and Inspector General Samuel Cooper wrote: “Lieutenant Brown, the officers, and crew of the Confederate steamer Arkansas, the third heroic attack upon the Federal fleet before Vicksburg, equaled the highest recorded examples of courage and skill. They prove that the Navy, when it regains its proper element, will be one of the chief bulwarks of national defense and that it is entitled to a high place in the confidence and erection of the country.” [37]

COST OF VICTORY

All of the accolades did not reflect upon the damage wrought upon Arkansas and its crew. When General Van Dorn rushed to congratulate Brown and his crew, one of the general’s staff officers, Clement L. Sulivane, commented in horror that the “smoke was still rolling around…the survivors of the crew, stripped to the waist and blackened with gunpowder, were just beginning to clean decks, and altogether the most frightful scene of war that was ever presented to my eyes.”[38]

Lieutenant George W, Gift recalled that on the inside of the casemate, “a giant heap of mangled and ghastly slain lay on the gun deck, with rivulets of blood running away from them. There was a poor fellow torn asunder, another mashed flat, whilst in the ‘slaughter-house’ brain, hair, and blood were all about. Down below fifty or sixty wounded were groaning and complaining, or courageously bearing these ills with a murmur.” [39]

The Arkansas was severely damaged. Port side iron rails were loose in some places and completely blown off in others. Gift wrote, “We got through hammered and battered through. Our smoke stack resembled an immense nutmeg-grater, so often it had been struck, and the sides of the ship were spotted as if it had been peppered. A shot had broken our cast-iron ram. Another had demolished a hawse pipe. Our boats were shot away and dragging. [40]

S. Flatau was in charge of a company of artillerymen and saw the terrifying carnage and destruction within the casement and noted: “The embrasures or portholes, were splintered, and some were nearly twice original size; her broadside walls were shivered, and great slabs and splinters were strewn over the decks of her entire gunroom; her stairways were so bloody and slippery that we had to sift cinders from the ash cans to keep from slipping.” [41]

MORTIFICATION AND REVENGE

The morning’s events mortified Farragut. He wrote to Davis: “We were all caught unprepared for him, but will go down and destroy him.” Davis was more cautious and wrote, “my friend the admiral says we are to act ‘regardless of consequences…This is the language of a Hotspur.” [42] Farragut told everyone in his orders to attack: “No one will do wrong who lays his vessel alongside of the enemy or tackles the ram. The ram must be destroyed.” [43]

Davis agreed to bombard the Vicksburg batteries with his ironclads to cover for Farragut’s fleet movement downriver. Unfortunately, Farragut’s fleet did not get underway, in two columns, until after dark due to the storm. So as they passed Arkansas, the port column steamed to within 30 yards of the Mississippi’s eastern back. They could not see Arkansas as it was rust-colored and docked against the red soil river bank. So Union ships fired at the Confederate ironclad’s muzzle flashes. The USS Oneida sent a shot that hit Arkansas and pierced the port side, a few inches below the waterline. The shot passed through the sickbay and into the engine room, where it damaged machinery. Three crewmen were killed and three others wounded. The Federals were, nevertheless, unable to destroy Arkansas. In turn, the remaining exhausted crew members were able to return fire. Supposedly, one shot from the Confederate ironclad disabled USS Winona’s engines and waited for events to follow. [44] This was the most humiliating day of Farragut’s career. [45]

UNDER PRESSURE

Flag Officer Davis thought it best to destroy the ram with mortar fire beginning July 16, 1862. The Arkansas had to be continuously moved so the mortars could not find the range. This tactic failed to strike Arkansas.

Meanwhile, Brown was desperate to repair his ship and to recruit more men as his crew had been badly depleted. Van Dorn gave Commander Brown permission to recruit soldiers under his command. It was a difficult task as stories of the carnage found on the ironclad’s casemate were disturbing, and few volunteered for service on the ironclad.

By July 19, Arkansas’s engine had been somewhat repaired, and the ironclad attempted to attack the mortar fleet. Unfortunately, one of the ironclad’s engines broke down, and the ship had to be moved back to its moorings.[46]

THE RAM MUST BE DESTROYED

Farragut, whose fleet was now below Vicksburg, continued to call upon Davis to sink the troublesome rebel ram. Lt. Col. Charles Rivers Ellet advised Davis and Farragut of his scheme to destroy Arkansas. The concept for the ironclad USS Essex, commanded by the brother of David Dixon Porter and foster brother to Farragut, Captain ‘Wild Bill’ Porter, was to attack Arkansas at night.

The Essex was built from the steamer New Era. The Essex’s battery had been upgraded in early-to- mid-1862 to include one X-inch shell gun, three IX-inch Dahlgrens, one 32-pounder, one 12-pounder, and two 50-pounder rifles. Ellet’s idea was for Essex “to grapple the Arkansas and drag her into the steam and fight her broadside to the broadside.” While this maneuver occurred, Ellet was then to dash in with Queen of the West to ram the Confederate ironclad. Despite this planning, the attack was poorly coordinated between Davis, Ellet, and Porter.[47]

Meantime, all was not well on Arkansas; the ironclad was certainly not prepared for any type of engagement. One engine was disabled. Brown had only enough men on board to man three guns. The ironclad’s bow was facing upstream, and it was moored to the riverbank. They did not expect that their ship would soon be attacked.[48]

RAMMING SPEED

Just before dawn on July 22, 1862, the ironclads Benton, Louisville, and Cincinnati positioned themselves. They opened fire on the Confederate upper batteries to cover the movement of the Union ram and ironclad. The Essex got underway at 4:14 a.m., and Queen of the West soon followed. However, it was delayed by miscommunication between Ellet and Davis. The Essex steamed toward Arkansas at cross-current, intent on ramming; however, as Essex approached, the Confederates threw off their bowlines and swung the bow out toward the Essex. The Arkansas then fired its forward 64-pounders; yet, the shot had no effect upon the Union ironclad. The Essex then fired into the Confederate ironclad with great success.

The first shot struck near the forward porthole breaking the rails and sending fragments into the casemate, wounding several men. Another shot broke through the casemate, crossed to the starboard side, and hit a broadside gun, injuring several crew members. George Gift later commented that the shots were fired at such close quarters that “our men were burnt by powder from the enemy’s gun.” [49] The Essex then grazed along Arkansas’s side, ran up onto the river bank, and was hit 42 times. After 10 minutes of this pounding, Essex was able to slip off the back and head downriver to join Farragut’s fleet. The Union ironclad suffered only one killed and three wounded; whereas, during this part of the action, Arkansas lost six killed and six wounded. [50]

Now it was time for Queen of the West to strike. The Confederates could barely defend their vessels with only enough men to man two guns. Ellet misjudged his speed, and his ram passed by Arkansas. The Queen of the West turned about and attempted to ram against the current. This did no damage to Arkansas. The ram was hit by several shells by the Vicksburg batteries and Arkansas. Arkansas’s final shot skipped across the water several times before striking the Union ram. While riddled with shot, Queen of the West suffered no casualties.[51]

NEW DEPOSITIONS

The Federals’ failure to destroy CSS Arkansas under the Vicksburg bluff on July 22, 1862, was debilitating to Union leadership. The river was dropping, and Farragut requested and received permission to return to New Orleans. Sickness prevailed in the Union ships. Davis knew that there was nothing he could do to bombard Vicksburg or Arkansas into submission. So, he moved the Western Gunboat Flotilla to Helena, Arkansas. [52]

THE FOOLISH EARL VAN DORN

With the Union fleets steaming away from Vicksburg, Commander Isaac Newton Brown was granted sick leave and went to Grenada, Mississippi, to recover from his wounds. Before he left, he informed Van Dorn that Arkansas’s engines could not be used without extensive repairs. Brown also ordered Stevens not to move the ironclad anywhere…damages had not been thoroughly repaired, Arkansas still did not have an adequately trained crew, and the engines were unreliable.

As soon as Brown left, Van Dorn became determined to recapture Baton Rouge with Major General J. C. Breckenridge’s division. This movement required Arkansas to support Confederate assaults and counter Union gunboats there. Accordingly, he ordered Arkansas to go down the river to Baton Rouge. Lt. Stevens cited Commander Brown’s orders and noted that the ironclad was still under repair for damages sustained during the July 15 and 22 fights. Furthermore, the engines were so defective that George Washington City, the chief engineer, stated that the machinery could break down at any moment. City became ill and was replaced by an army officer with no marine engine experience. Stevens pleaded with Van Dorn to call off the action. When Van Dorn referred that matter to the CS Navy’s senior officer on Mississippi, Flag Officer William Lynch, refused to get involved. Van Dorn then stated, “…her deemed [Arkansas] to be as formidable in attack of defense as when she defied a fleet of forty vessels-of-war, many of them ironclads,” and overrode all objections to the ironclad’s immediate use.[53] Brown rose out of his sick bed in Grenada and rushed to Vicksburg to try to stop the operation. He arrived too late!

LAST VOYAGE OF CSS ARKANSAS

Lieutenant Henry K. Stevens, the ironclad’s executive officer, now in command of Arkansas, wrote on August 2, 1862: “We are ordered off tomorrow and expect a pretty tough time of it… Our destination is Baton Rouge. It is not just to send us in our condition; but, I am ready to do what I can.” [54] Stevens was correct about Arkansas not being ready for any offensive movement. This was critical as the engines had not been properly repaired after Arkansas’s July battle. Furthermore, the ironclad’s crew was comprised of mostly untrained soldiers from the Vicksburg garrison. Stevens feared for the worst; yet, he was well-prepared for the future battle. He wrote his wife: “We have been shown that we need not trust iron sides nor cotton protection, but the uplifted arm of God.” [55]

BOUND FOR BATON ROUGE

During the early morning hours of August 3, 1862, Arkansas steamed away from the dock at Vicksburg, destination Baton Rouge. Stevens was forced to steam at full speed to reach Baton Rouge in time to support Major General John C. Breckenridge’s attack on the city. The next day the engines became so troublesome that the ship was stopped and anchored along the shore for repairs during the night. The Arkansas got underway; however, it suffered mechanical issues when the starboard engine broke down. The port engine continued to race, causing Arkansas to spin until it grounded on some cypress stumps. The working engine would overpower the turning force provided by the rudder. As the machinery was repaired, crew members worked Arkansas off the stumps. In doing so, they jettisoned some of the deck iron. [56]

Once the engine was repaired, Stevens and the pilot planned to attack USS Essex at Baton Rouge by ramming. The engineer protested, stating, “It will be impossible for me to put them (engines) in fit condition to render efficient aid to propel the ship into action…The steam drum has now the entire weight of the gun deck. If it should be possible to use the ram, in my judgement the weak condition of the ship would carry (the steam drum) away…”[57]

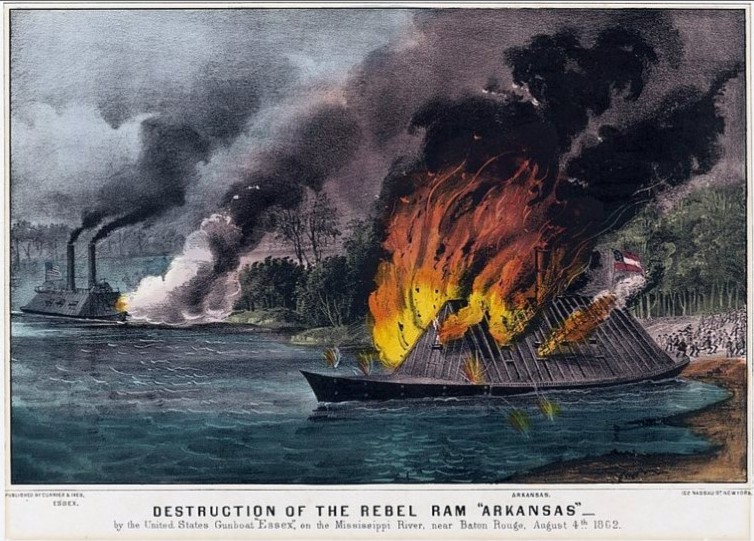

ENGINE FAILURE

Once Arkansas’s engines were repaired, Stevens steamed the ironclad to a landing to coal. On August 6, 1862, Stevens took his ship within sight of Baton Rouge. The USS Essex steamed toward Arkansas. As the Confederates prepared to ram Essex, one engine broke down, and moments later, the other stopped. Stevens had no choice but to scuttle his ship. The crew abandoned ship after strewing powder on the deck and setting the cotton backing on fire. The ironclad floated downriver, ablaze, blowing up about midday.

Stevens and his men watched the ironclad float downriver. When the fire reached Arkansas’s guns, they discharged. “It was beautiful, Lieutenant Stevens wrote, “To see her, when abandoned by commander and crew, and dedicated to sacrifice fighting the battle on her own hook..” [59] The Arkansas was the last ironclad of those they had begun in 1861 to defend the Mississippi River. The Union Anaconda had begun to squeeze its victim toward defeat.

ENDNOTES

- Myron J. Smith, The CSS Arkansas: A Confederate Ironclad On Western Waters, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, pp. 33-36.

- William N. Still Jr., Confederate Shipbuilding. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 1969,p. 29.

- J.E. Kaufmann and H.W. Kaufmann, Fortress America: The Forts That Defended America From 1600 To The Present. Da Capo Press, Cambridge, MA, p. 147.

- William N. Still Jr., ed., The Confederate Navy. The Ships, Men And Organization 1861-65. Annapolis, MD., Naval Institute Press, 1997, p. 53.

- Cynthia E. Moseley, “The Naval Career of Henry Kennedy Stevens as Revealed in His Letters, 1839-1863,” (M.A. thesis, University of North Carolina, 1951), pp. 305-306.

- IBID, p. 306.

- Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, (Hereinafter, referred to as ORN), ser. II, vol 1, p. 763.

- ORN, ser.1, vol.22, p. 838.

- Still, Iron Afloat, p. 63.

- Raimondo Luraghi, A History Of The Confederate Navy, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1996, p. 131.

- Maryland Adjutant General Office, November 2019. en.wikipedia.org/Wiki/Adjutant_Gereral_of_Maryland.

- Moseley, pp. 307-308.

- ORN, ser. 1, vol. 18,p. 647

- Still, Iron Afloat, p. 64.

- ORN, ser.1, vol.18, p. 647.

- Still, Iron Afloat, p. 71.

- Smith, pp. 52, 54, 97, 101-120.

- Smith, pp.122-123.

- Paul H. Silverstone, Civil War Navies, 1855-1883, Annapolis, MD: 2001, p. 152.

- Smith, pp. 127-129.

- Faust, pp. 777-778.

- ORN, ser. 1, vol.18, p. 650.

- Smith, pp. 137-145.

- J. Thomas Scharf, History of the Confederate Navy From Its Organization to the Surrender of Its Last Vessel. New York: Gramercy Books, 1996, pp. 310-311.

- Henry Walke, Naval Services and Reminiscences of the Civil War in the United States in the Southern and Western Waters During the Years 1861, 1862, and 1863, With a History of the Period Compared and Corrected from Authentic Sources. New York: F. R. Reed and Company, 1877, p. 307.

- Smith, pp. 155-160.

- Still, Iron Afloat, pp. 68-69.

- Charles Henry Davis Jr., Life of Charles Henry Davis, Rear Admiral, 1807-1877. New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1899, pp. 262-263.

- Still, Iron Afloat, p. 69.

- IBID, p. 70.

- Smith, pp. 190-195.

- ORN, Ser I, vol. XIX, p. 747.

- IBID, pp.195-200.

- Civil War Naval Chronology, Washington, D.C., Naval History Division, Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, part 2, p. 81.

- IBID, p. 83.

- Scharf, p. 322.

- Scharf, pp. 322-323.

- Clement L. Sulivane, “The Arkansas in Vicksburg in 1862,” Confederate Veteran XXV, 1917, pp. 313-314.

- Scharf, p. 320.

- IBID.

- L.S. Flatau, “A Great Naval Battle,” Confederate Veteran XXV, 1917, p. 459.

- Davis, Charles Henry Davis, pp. 262-26.

- Charles L. Lewis, David Glasgow Farragut, Annapolis, MD., United States Naval Institute Press, 1943, p. 287.

- Smith, pp. 222-227.

- Still, Iron Afloat, pp. 72-73.

- Donald L. Miller, Vicksburg: Grant’s Campaign that Broke the Confederacy. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2019, 160-161.

- John D. Milligan, Gunboats Down The Mississippi, Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute Press, 1965, pp. 87-90.

- George W. Gift, “The Story of the Arkansas,” Southern Historical Society Papers, January-May 1884, pp. 168-169.

- IBID, p.169.

- Still, Iron Afloat, pp. 73-74; and Howard P. Nash Jr., A Naval History Of The Civil War, New York: A.S. Barnes and Company, 1972, pp. 148-149.

- H. Allen Gosnell, Guns on the Western Waters, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1949, p. 130.

- Miller, pp. 163-164.

- Scharf, p. 332.

- Moseley, p. 312.

- IBID.

- Smith, pp. 122-123.

- Still, p. 77.

- Gosnell, p. 133.

- Still, Iron Afloat, p. 78; and ORN, ser. 1, vol., 19, p. 138.