Twenty. One to do the actual screwing and nineteen to write articles providing conflicting details on exactly how the installation of the light bulb was accomplished. In the instance of the story I’m going to tell, the question is “how many newspaper articles did it take to get the story right?” The answer is about 125 articles in ten newspapers from nine different cities in four different countries.

Researching the story was prompted by a painting in the collection that contained the inscription “Ship H.R. COOPER, Capt. I. Lapham, rescuing the crew from the wrecked ship, BOOMERANG, Capt. G. B. Crow. March 27th 1856. Lat. 40.35n Long. 49.40w.” Two additional details were provided by an object acquired with the painting—a gold medal awarded by the British government to the Helen R. Cooper’s captain: his first name, “Isaac,” and the full name of the vessel: Helen R. Cooper. Beyond this I didn’t know anything about the incident and there wasn’t any historical information in the object file.

As usual, I started my research by hitting the Internet and within a short time found a newspaper article in the Sydney Morning Herald in Australia dated July 7, 1856. The article was about ten sentences long. My first thought was “well this is cool, I’ve got enough to provide a description of the incident.” But you guys know me, the story just didn’t seem complete and it was driving me nuts so I continued to search. After three hours on Newspapers.com I had accumulated more than 30 articles about the incident—and NONE of them told the whole story and all of them seemed to contain mistakes of one kind or another.

Some of the mistakes seemed reasonable—like assuming that when a ship known to be sinking can no longer be found that it must have capsized and taken everyone aboard with it. Other mistakes just made me laugh—like the complete inability to get the name of the rescuing vessel correct. Remember, the name of the ship is Helen R. Cooper. I found it variously identified as the: 1) Helen Cooper, 2) Helen K. Cooper, 3) Ellen R. Cooper, 4) John R. Cooper, and 5) Allan R. Cooper. One newspaper even used two different names in the same article!

SO! Here’s the full story. I apologize for the length of it, but after all of the work I did to separate fact from the fiction I didn’t want to leave anything out!

The ship Boomerang (1823 tons) was built in Quebec in 1853 by Theopilus St. Jean. The ship was purchased by James Baines and Co.’s Black Ball Line in 1855 for use in transporting emigrants from Liverpool to Australia. A temporary depression in the trade led the ship’s owners to send Boomerang to Mobile, Alabama to bring home a shipment of 4300 bales of cotton. The vessel, captained by G. B. Crow, sailed for Mobile on November 2, 1855 reaching the port sometime before January 8th, 1856.

Boomerang left Mobile on March 3rd, 1856 with 47 crew and two passengers. On March 23rd the vessel ran into a “terrific gale from the WSW.” The ship suffered through the storm for more than 48 hours before the vessel’s “patent steering apparatus” gave way and the ship “broached to” (i.e. the ship’s bow suddenly turned into the wind because of the force of the sea striking the stern).

As the crew worked to repair the steering gear they discovered the rudder was severely damaged. Soon afterwards, the ship sprang a leak and began rapidly filling with water. As the storm continued and the water rose, the crew threw everything unnecessary off the ship. It was also reported that the ferocity of the wind blew the furled sails right off the yards.

On the 25th the gale moderated for a time giving the crew an opportunity to attempt the repair of the rudder but they were unsuccessful. As the water level inside Boomerang increased, the cargo became saturated on the lee side of the ship (the side protected from the wind) which caused Boomerang to begin settling on her “beam ends” (in other words the ship was laying on its side). On the 26th, the gale re-intensified and forced the crew to wear the ship onto the opposite tack and set as much sail as possible to try and push the ship back into an upright position. Unfortunately, the maneuver was unsuccessful and the ship continued to lay on its port side. Even worse, Boomerang’s change in direction now exposed the ship’s deck to a heavy weather sea and waves were frequently breaking over or on board the vessel.

Around 4:00 PM on the 26th, while it was still “blowing a very heavy gale,” the crew of Boomerang spotted the American ship Helen R. Cooper and hoisted a distress signal. Upon seeing the signal, the Cooper’s captain, Isaac Lapham, immediately changed direction and came to their aid. At Captain Crow’s request, Lapham kept the Helen R. Cooper near Boomerang throughout the night. Luckily, the intensity of the storm lessened during the overnight hours.

The following morning showed Boomerang settling further and further to port and the decision was made to cut away the foremast to try and forestall or prevent a capsize. Soon afterwards, the mainmast fell and as it went it crushed the bow of Boomerang’s longboat as it was being lowered into the water. Around noon, the weather had moderated enough to commence the abandonment of the vessel using Boomerang’s last remaining boat—a little pinnace. With great difficulty, they managed to transfer 43 persons and most of their belongings to the Helen R. Cooper. One newspaper reported that an American seaman drowned during the effort.

Unfortunately, Boomerang’s first mate, Adam Thompson, the carpenter and three seamen were prevented from leaving the stricken vessel by rising waves and the approach of nightfall. Intending to rescue the five men who remained on board when daylight returned Captain Lapham attempted to keep the Helen R. Cooper close to the floundering Boomerang throughout the night, but the squally weather soon separated the ships. When dawn arrived on March 28th Boomerang was nowhere to be seen. Captain Lapham searched the area for several hours hoping to spot the missing ship, but when nothing turned up he turned his ship for England.

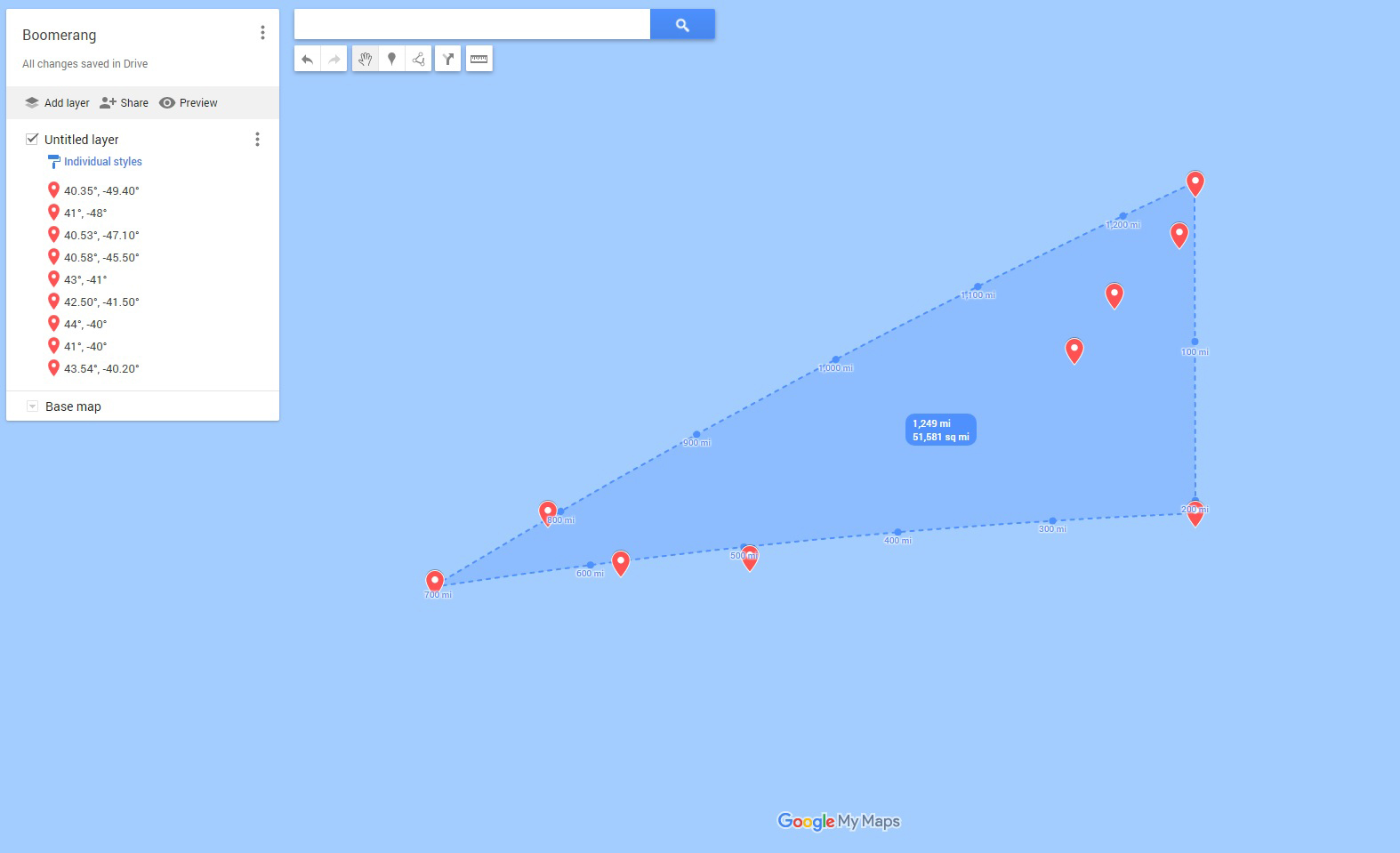

Although the newspapers originally reported that Boomerang had capsized and the men trapped on board had drowned, Captain Crow believed the ship had remained upright and was hopeful the men would be rescued by another vessel. Crow’s belief was justified just three days later when the ship American Congress, heading from New York to London, stumbled upon the wreck (in 41° latitude, 48° longitude) and rescued the five stranded sailors.

American Congress wasn’t the only ship to spot the abandoned Boomerang:

On March 30th, the ship J. P. Morse reported seeing the dismasted and abandoned Boomerang still flying a distress signal. The Morse’s captain said another vessel was nearby and had apparently sent a boat over to survey the wreck and recover any survivors. The boat returned to the unidentified vessel without anyone else on board so it probably wasn’t the American Congress.

On March 31st, the crew of the bark John Gardner indicated they had seen Boomerang nearly on her beam ends and with her fore mast and main mast gone floating in latitude 40°53’ north, longitude 47°10’ west.

Boomerang was spotted again on April 5th by the ship Muscongus in latitude 40°58’ north and longitude 45°50’ west. Since the abandoned Boomerang was still flying distress signals Muscongus ran down on the vessel and boarded it. A check showed it was abandoned with six feet of water in the hold, a strong list to port, with its bowsprit, jibboom, mizenmast and topmast standing but missing its rudder, fore and main masts. The boarding sailors hauled down the distress signal and Muscongus continued its voyage to Greenock, Scotland.

On April 14th the ship Saranak spotted Boomerang at 43° latitude, 41° longitude and reported the vessel upright and rolling pretty equally from side to side in the trough of the sea.

While sailing from Le Havre to New York, the ship Fairfield spotted Boomerang on April 17th in latitude 42°50’, longitude 41°50’. The sea was rough so they did not board the vessel but the captain, named Hathaway, reported the fore and main masts gone, the mizenmast standing, the rudder gone, cotton in the poop, her decks dry and hatches on with apparently little or no water in her (I’m not sure how he would know this without getting on board! Which begs the question…once a vessel is so full of water to be on its beam ends how the heck does the water get back out when no one is on board forcing it out???).

Boomerang was spotted again on April 18th by the ship Endymion who reported the vessel dismasted and waterlogged. At this point I thought “so much for Captain Hathaway’s interpretation of the situation!” but the ship Ward Chapman arrived in Liverpool in May and reported seeing the Boomerang on April 20th “perfectly upright, and floating light.”

The ship Royal Arch spotted Boomerang with the ship Chanticleer close by in latitude 41° longitude 40° on April 26th. The captain reported that Chanticleer’s master had been on board and found the vessel perfectly tight. This was slightly contradicted when Chanticleer arrived back in London in July and reported seeing Boomerang in latitude 43°54 north, longitude 40°20’ west in a waterlogged condition on April 21st.

With so many vessels spotting the derelict ship so frequently it was determined to try and salvage the vessel and its cargo. It was reported on May 22nd that the sum of £5,000 had been accumulated between the cities of Liverpool and London in order to undertake the salvage of the vessel (valued at £22,000) and her freight (valued between £35,000 and £60,000). As you would expect, the vessel was never seen again after Chanticleer’s sighting on April 21st.

One of the vessels sent to find Boomerang was British Flag. The ship was spoken to on June 11th in latitude 48° north, longitude 29° west and it was reported all was well and they were continuing to search for the ship. The ship was spoken to again in latitude 11° north, longitude 26° west on the 5th of July as it headed for Bombay following an unsuccessful search for Boomerang.

The United States also participated in the search for the vessel sending out the schooner Stetson, but the vessel arrived in Queenstown on July 10th without seeing any sign of the missing ship.

While all of these vessels were busily spotting Boomerang, the two ships carrying the rescued crew and passengers were making their way to England. On April 8th, Helen R. Cooper met a fishing boat off Land’s End and transferred Boomerang’s captain, his wife, the second mate and sixteen crew on board for transport to Falmouth. The vessel then headed for its original destination, Le Havre, and arrived on April 13th discharging the remaining crew and two passengers.

The American Congress landed the five crewmen it rescued in London on April 21st and they immediately headed for Liverpool. The men reported 7 feet of water in the Boomerang’s hold when they left the ship. On a weird side note, when Boomerang’s first mate, Adam Thompson, arrived in Liverpool he discovered that his sextant and a large quantity of clothes had been stolen from his sea chest. It was later discovered that Boomerang’s boatswain, John Dickenson and sailmaker David Blucker (whose first name might have been Howard–gotta love the press’s determination to get the details of their stories right) had taken the materials and sold them, probably assuming Thompson was dead. Boomerang’s captain saw the men go into an optician’s shop in Falmouth and upon hearing the sextant had been in the mate’s bag and was missing reported the incident to police. The shop was checked and the sextant was recovered for a payment of £2. The theft set off a huge legal rigmarole and I was never able to determine how the case was resolved.