While troubleshooting the rehousing of some objects we ran across an odd flag and discovered that it was related to an interesting historical event, the anniversary of which occurs in the month of August. I know it’s unusual to say that a whole month plays host to an anniversary but it’s only because that’s pretty much how long it took for the event to occur.

The event was the first submarine transit of the Northwest Passage, one of only two times that has occurred in history. It was accomplished by USS Seadragon (SSN-584), the US Navy’s fourth Skate-class nuclear powered submarine. While making the historic transit, Seadragon conducted the first hydrographic survey of the Northwest Passage; became the first vessel to navigate UNDER an iceberg; and the third US Navy submarine to surface at the North Pole (the first two were her sister ships USS Skate and USS Sargo). [There was also one more crazy “first” that happened on this voyage that I’ll discuss later.]

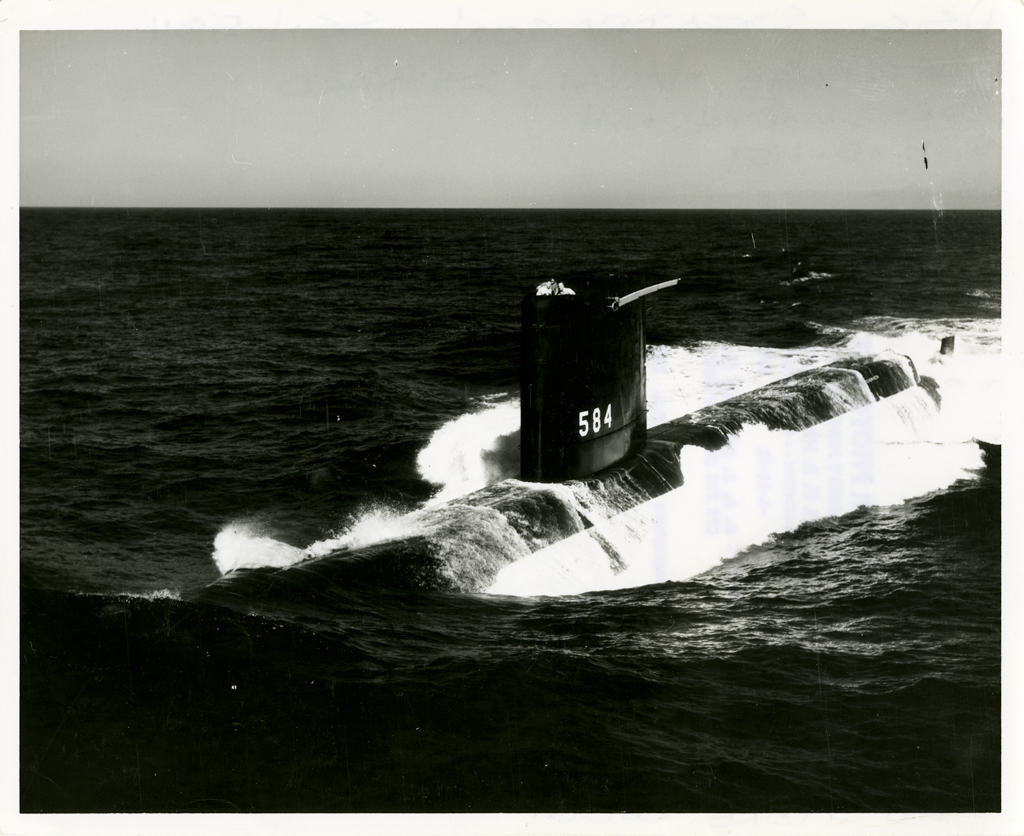

The 2,907 ton, when submerged, USS Seadragon was built at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine and commissioned on December 5, 1959. The ship was commanded by George Peabody Steele II. Destined for the Pacific Fleet, the US Navy decided to have the submarine try and sail to the Pacific through the Northwest Passage.

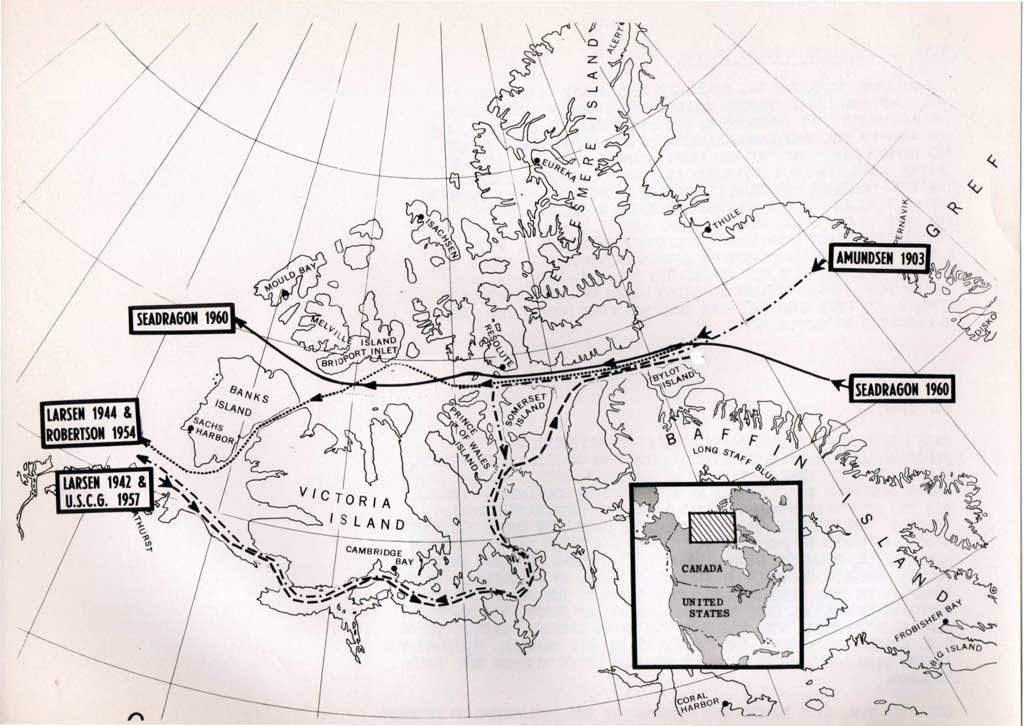

The proposed route would take Seadragon up through the Davis Strait and Baffin Bay and then enter the Parry Channel at Lancaster Sound. Transiting the Northwest Passage through the Parry Channel had never been accomplished by any ship because heavy ice typically blocked the channel’s western end. This obviously wasn’t a problem for Seadragon because she intended to transit the channel under the ice. Sailing through the Parry Channel to reach the Beaufort Sea involved passing through the Barrow Strait, Viscount Melville Sound and finally the McClure Strait.

Since no sailing vessel had ever done it, the only one way to find out whether a submarine could make the passage was to try. As you would expect, charts of the area were useless and the sparse soundings available only showed shallow water. There weren’t even enough soundings available to know whether passages deep enough and wide enough for a submarine to pass through even existed!

So what the heck did Captain Steele use as a guide? Why the best thing he had available, of course! Steele used a copy of the journal compiled by Sir William Edward Parry during his 1819 over-the-ice transit of the channel that now bears his name. Although Parry’s journal was nothing more than a rough guide and didn’t provide any soundings whatsoever, Steele and the Navy believed (um, I think “hoped” might be a better word) that the ship’s navigation equipment would provide adequate warning of any high peaks, deep plunging ice or shallows along Seadragon’s course.

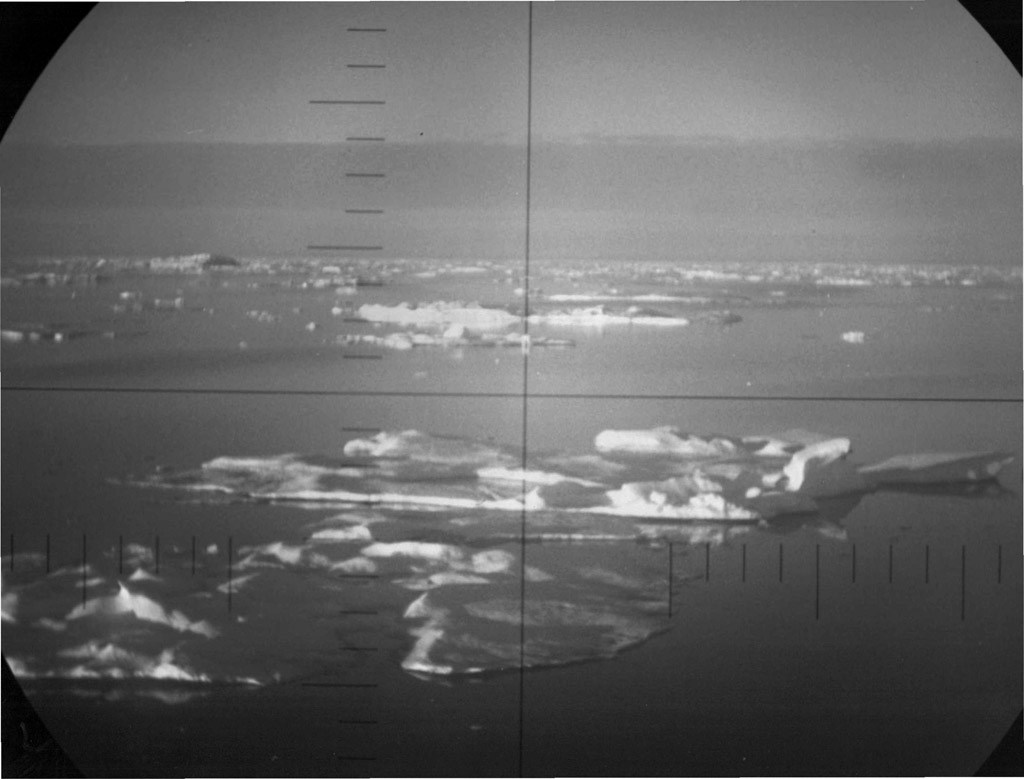

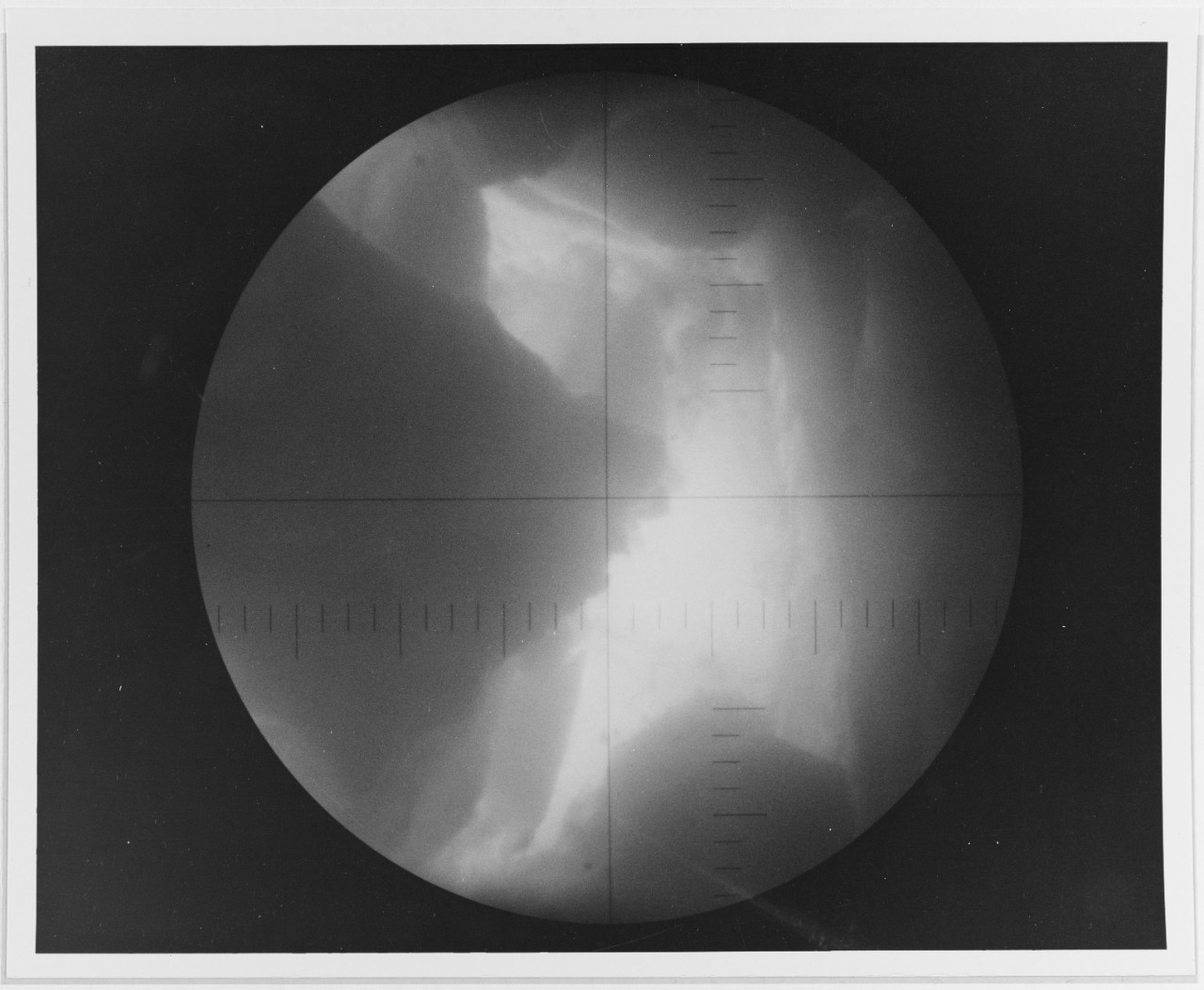

Of course, sonar had never been put to a test like this one. When the ship was in shallower water with an ice canopy overhead how would the crew know if the returning sonar echoes were coming from the ice above or from obstacles reaching up from the bottom? To try and answer these questions Seadragon was equipped with several unique pieces of equipment: an upward-beamed echo sounder; several types of fathometer, one of which measured the thickness of the ice overhead; a rate-of-rise meter; a precision depth recorder; an ambient light meter (which helped determine ice thickness); and a totally new piece of equipment–an iceberg detector.

Seadragon also carried the prototype of a new piece of a sonar equipment called a “polynya delineator” (a polynya is a stretch of open water surrounded by ice) as well as a new shipboard team: the plotting party. The job of the crew members on this team was to plot the polynyas and icebergs so they could be “fingerprinted” and used as guideposts while the submarine was traveling submerged.

In order to calibrate Seadragon’s detection and navigation equipment and help the crew understand the complexities of operating under the ice, Steele did several training runs under icebergs as they neared the ice pack in the Arctic Circle. The first test was done with a small 26-foot high, 200-foot long iceberg fragment that Steele called a “bergy bit.” It was 82-feet deep and had a mass of about 3300 tons (more than Seadragon itself). Something the crew had to be constantly aware of (and I know you’ve all seen it happen if you’ve watched any television show that involved icebergs) was the stability of the icebergs they were cruising under. Maintaining good clearance was vital in case the iceberg suddenly calved off a large piece or readjusted its equilibrium.

During the first test, the crew learned that the slow drift of the ice caused their sonar bearing to always be a degree or more off. They solved this problem by relying on the bearing provided by the new iceberg detector. They used the depth reading provided by the upward-beamed fathometer to reset the iceberg detector to indicate the depth of the iceberg they were training with. The submarine then made repeated sweeps under the “bergy bit” until they were confident their equipment was well calibrated.

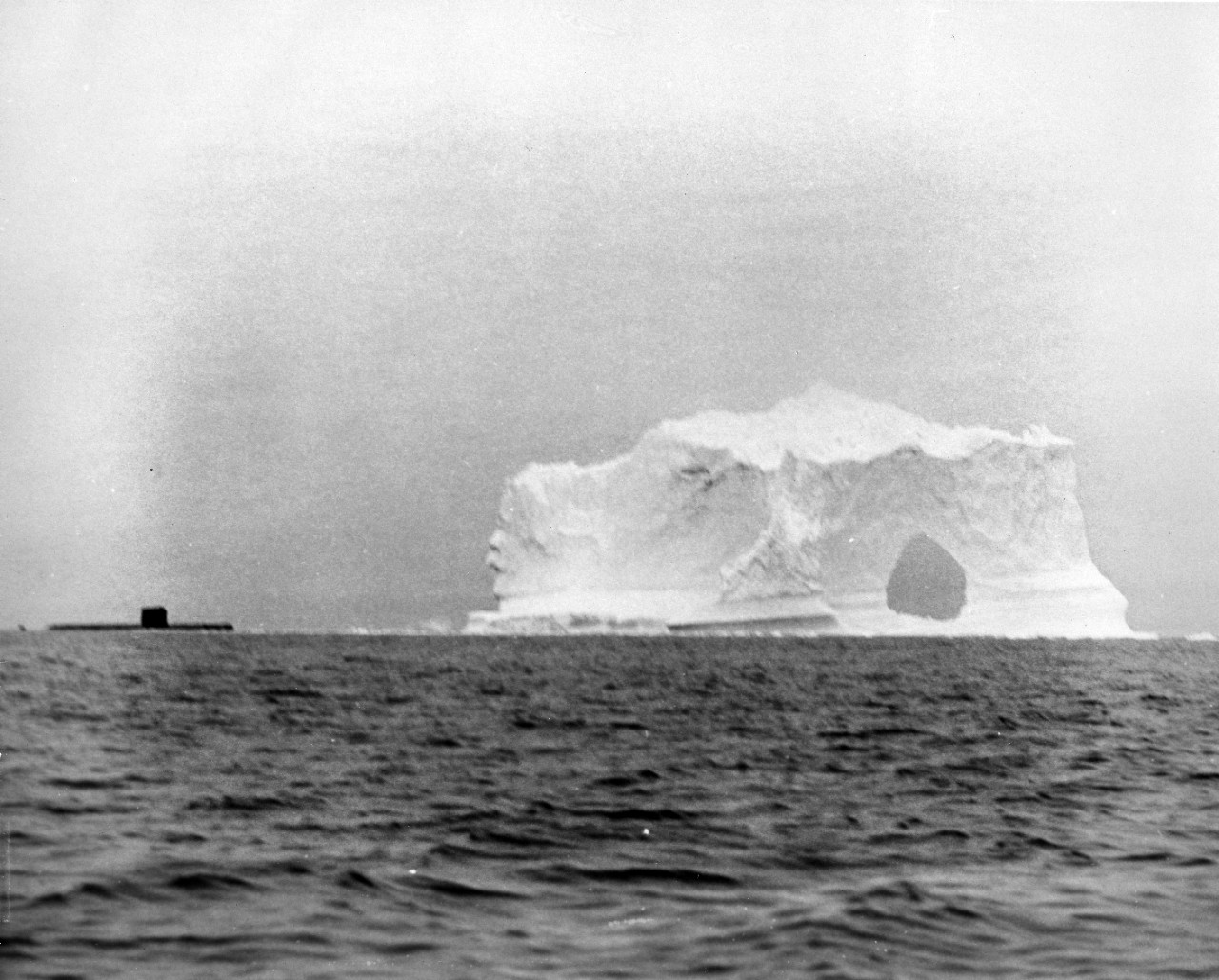

To test the effectiveness of their equipment and what they had learned, Steele had the crew perform a second test with the largest iceberg they could find–a 74-foot tall iceberg located one mile north of the Arctic Circle. On this test they planned to make repeated charges at the iceberg increasing Seadragon’s speed each time to see how well the ship’s sonar could detect it. This test would give the crew confidence that the equipment always gave fair warning in time to avoid a collision with an iceberg.

When they reached top speed, Steele put Seadragon within 700 yards of the iceberg and then made a sharp skidding turn and headed away. The resulting pressure wave put so much stress on the iceberg that it emitted what sounded like a loud underwater explosion. The crew thought the iceberg might have calved off a large section but its dimensions remained unchanged. Despite the continuous noise coming from the iceberg Steele decided to finish the exercise and make the first ever run under the iceberg.

Seadragon made a clover-leaf pattern of passes under the iceberg’s center to determine its width, length and underbody shape. Knowing the underwater dimensions and shapes of icebergs would contribute to the understanding of their drift rates which would enable the International Ice Patrol to forecast iceberg positions more accurately between actual sightings. There had never been way of determining an iceberg’s draft or underwater shape until now. After the test, they had determined that the iceberg’s longest axis at the surface was 313-feet but its longest axis below the surface was a whopping 822-feet! It had an underwater draft of 108-feet and a mass of 600,000 tons.

Once the testing was complete, Steele headed for Baffin Bay knowing Seadragon could safely operate at any speed with no doubt that the equipment would warn them about what lay ahead.

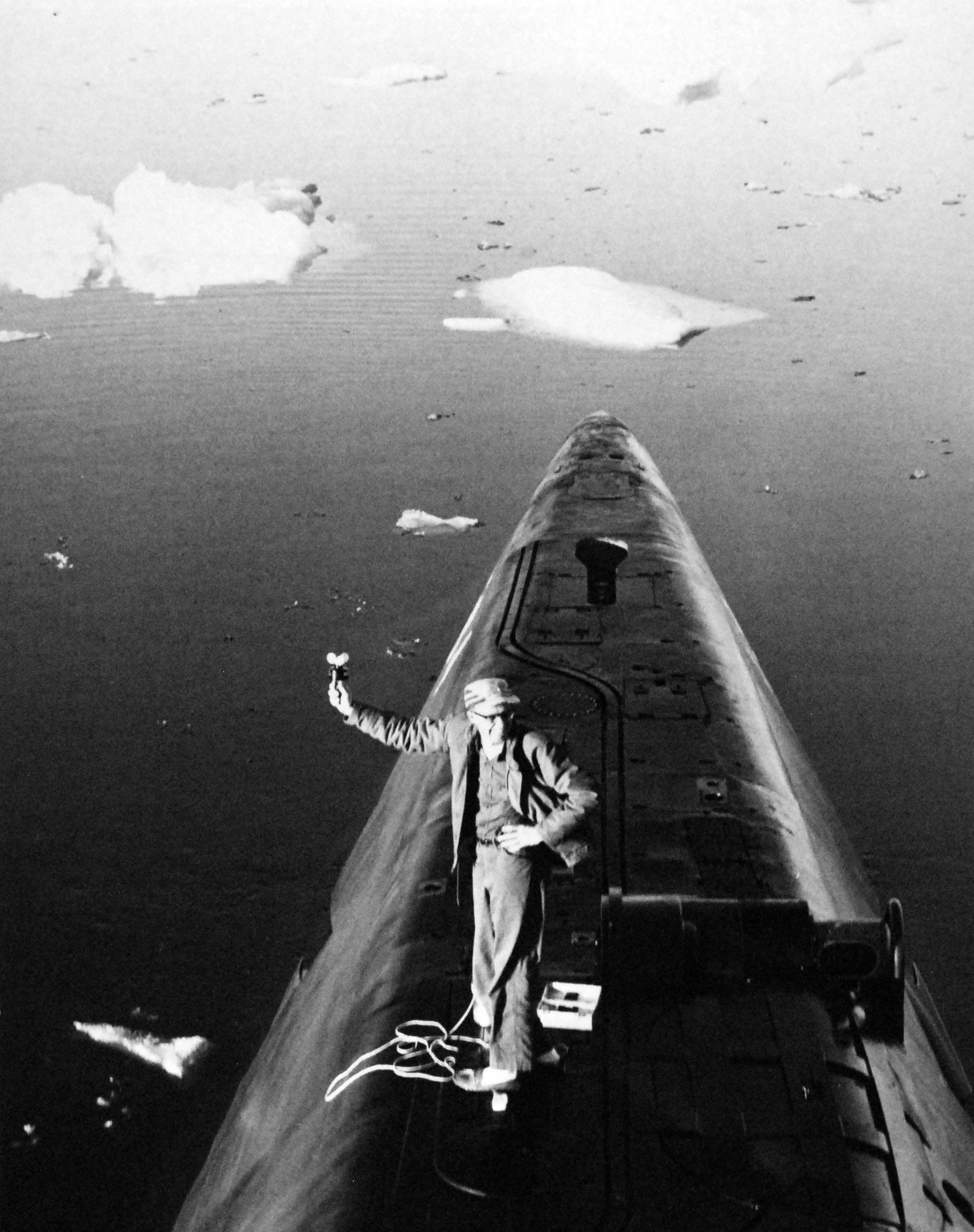

Once inside Baffin Bay they tested their equipment again with an even larger iceberg and discovered it’s draft was a remarkable 440-feet. Walt Wittman, a civilian ice forecaster with the Hydrographic Office and the sub’s resident ice expert, later calculated the iceberg had a mass of some 3 million tons! All-in-all Seadragon became the first and only submarine to examine the underneath of 22 icebergs in Baffin Bay and Lancaster Sound.

Transiting the Northwest Passage required the crew to slowly pick their way through myriad underwater channels, which at times shoaled so quickly they had to take evasive maneuvers. Seadragon completed the voyage through the Parry Channel on August 21, 1960 and headed for the North Pole; reaching it on August 25th.

It’s at this point that our flag finally makes its appearance! Before the voyage started, Captain Steele tasked the ship’s doctor, Lieutenant Lewis Seaton, with organizing a plan for survival on the ice. If something went wrong and Seadragon’s crew was forced to abandon ship, Steele figured they might have to survive a week on the ice before help could arrive. To accomplish this task Seaton took a nine-man survival team camping on the ice when they reached the North Pole. When Captain Steele decided to check on them, he was able to spot the location of the campsite by the presence of a lone rifleman stationed atop an upended ice floe with a flag fluttering beside him–the flag that’s in our collection!

And now we reach Seadragon’s final first! After surfacing and getting the submarine settled, one of the first tasks they undertook was the organization of the very first baseball game at the North Pole. But this was no ordinary game! The field was aligned with the pitcher’s mound as close to the North Pole as possible which set up some really crazy situations:

if a batter hit a “homerun,” he would circumnavigate the world as he rounded the bases;

if the ball was hit into right field, it flew into “tomorrow;” a ball hit to left field remained in the same day, but if it was then thrown to first base it entered “tomorrow”;

if the right fielder caught a fly ball, he caught it the next day which meant the batter could not be considered out for another twenty-four hours, but if the ball was caught as a line drive and thrown back towards second or third base, it was being thrown back into yesterday;

Double or triple plays could take several days to complete and, as you would expect with a field of ice, sliding into the bases took on a whole new, a somewhat dangerous meaning! During the game so many disputes broke out over what day and time an event had occurred that the umpires remained in a constant state of confusion. In the end no one remembered the final score or even the day game ended–the only thing they were sure about was that it had started on August 25, 1960.