Too many acronyms? There’s no such thing!

Over the past three years, our archival staff, with the support of several catalogers and the Digital Services department, have been working diligently on the Hidden Collections Grant sponsored by The Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR). This grant allowed us to catalog and digitize items that have been sitting in storage for years. Through the process, we discovered many exciting images we never knew we possessed. One of my favorite collections was a series from the Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation (HRPE) during World War II.

The Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation

The HRPE activated in 1942 under the jurisdiction of the Chief of Transportation. From 1942 to 1945, the port handled 725,880 passengers and 12,521,868 tons of cargo bound for the war front. It was the third busiest port in the United States. Several smaller installations including Camp Patrick Henry, Camp Hill, and the Norfolk Army Base comprised the collective Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation.

Women’s Army Corps

The Women’s Army Corps (WAC) began as an auxiliary unit on May 15, 1942. About a year later, on July 1, 1943, they received active duty status in the United States Army. One of three positions were open to women recruited to the WAC initially. The quickest recruits served as switchboard operators. The most technically savvy became mechanics. Meanwhile, the lowest scoring recruits were sent to work in bakeries. Career paths quickly opened up to include jobs such as postal clerks, drivers, stenographers, armorers, and typists. Approximately 150,000 women served during WWII both at home and abroad.

The speed with which women signed up began to stall in 1943 with a massive slander campaign aimed at the organization. Public opinion painted the WACs as sexually immoral. Potential recruits often heard that women who joined would be considered lesbians or prostitutes. Men were angry about losing non-combatant jobs. Women were upset by the uptick in competition and outsiders “taking over” their hometowns. Charitable organizations opposed the WACs receiving “special treatment.” In response, the army launched investigations but found no reason to disband the corps. They did discover, however, that the slander originated within the ranks of the U.S. military and by disgruntled or discharged WACs rather than foreign entities.

Despite the slander, the women serving during WWII did so with great enthusiasm and pride. General Douglas MacArthur said that the women of the corps were, “my best soldiers,” and that they worked harder, complained less and showed more discipline than the men. General Dwight D. Eisenhower echoed the sentiment saying, “their contributions in efficiency, skill, spirit, and determination are immeasurable.”

The Women’s Army Corps continued service until disbanding in 1978 and integrating with male service members.

WACs at The Mariners’ Museum

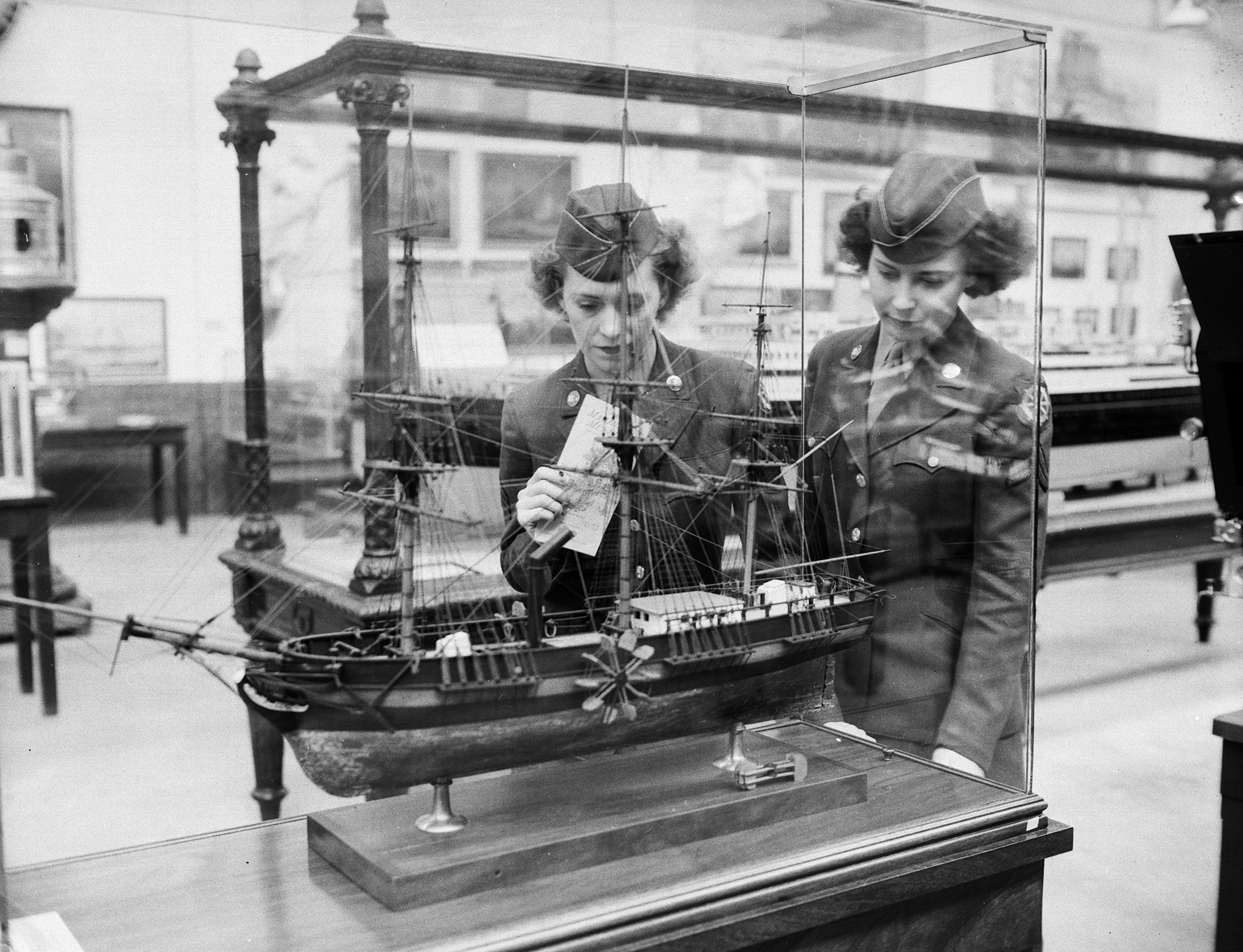

As a means of combating the slander against them, the Women’s Army Corps launched a fairly aggressive publicity campaign. The images focused on recruits participating in wholesome and cultural outings and activities. What better place for that than a museum? And what better museum in Hampton Roads than The Mariners’ Museum?

Trigger Warning: Museum professionals may want to look away. Inappropriate artifact handling ahead. You are warned!