This lengthy blog post began rather innocently when Bonham’s most recent Art of Time auction catalog arrived. One of the many varied aspects of my job is placing insurance values on objects so I regularly peruse catalogs for objects similar to those in our collection. In the catalog I noticed a Japanese pillar clock, called a shaku dokei, up for auction. While updating the value I noticed a name on the clock’s storage box—’C. E. Thorburn, USN’. Whenever I run across a name, especially one this unique, I immediately try to see if I can uncover the history of the original owner.

My first stop was Fold3, a genealogical research site specifically used to document military service. It’s a great site—but sadly super tricky to use as its search feature makes you want to rip your hair out. I immediately had a number of hits for the name Thorburn. I spotted a Thorburn on the USS Susquehanna in 1851-1852 which was really exciting because that’s when the ship was in the Pacific getting ready to head into Japan with Matthew C. Perry to negotiate the treaty that would open trade with America—unfortunately the name was “E. C. Thorburn” (a midshipman) so I wasn’t 100% sure it was the same person.

My next stop was the “Register of the Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy and Marine Corps.” The problem with this source is that you have to take it with a grain of salt because it almost never provides a correct or complete record of an officer’s movements within the Navy. This time however, it helped narrow down my subject to Charles Edmondston Thorburn. After several more weeks of painstaking research on Fold3 I had enough correspondence to reconstruct Thorburn’s movements from ship to ship. The topper, however, was a court martial document dated 1856 which carried Thorburn’s signature and it was a perfect match for the handwriting on our box.

While this was one of the most difficult and time consuming genealogical projects I’ve ever undertaken it was totally worth it!

Charles Edmondston Thorburn (1831-1909) was born in Virginia and entered the Naval Academy September 9, 1847 (16 years old) as a citizen of Ohio. His first cruise was on board the frigate USS Cumberland in July 1848 while the ship was stationed with the Home Squadron. In November 1850 he was briefly attached to the frigate St. Lawrence which was stationed with the Mediterranean Squadron.

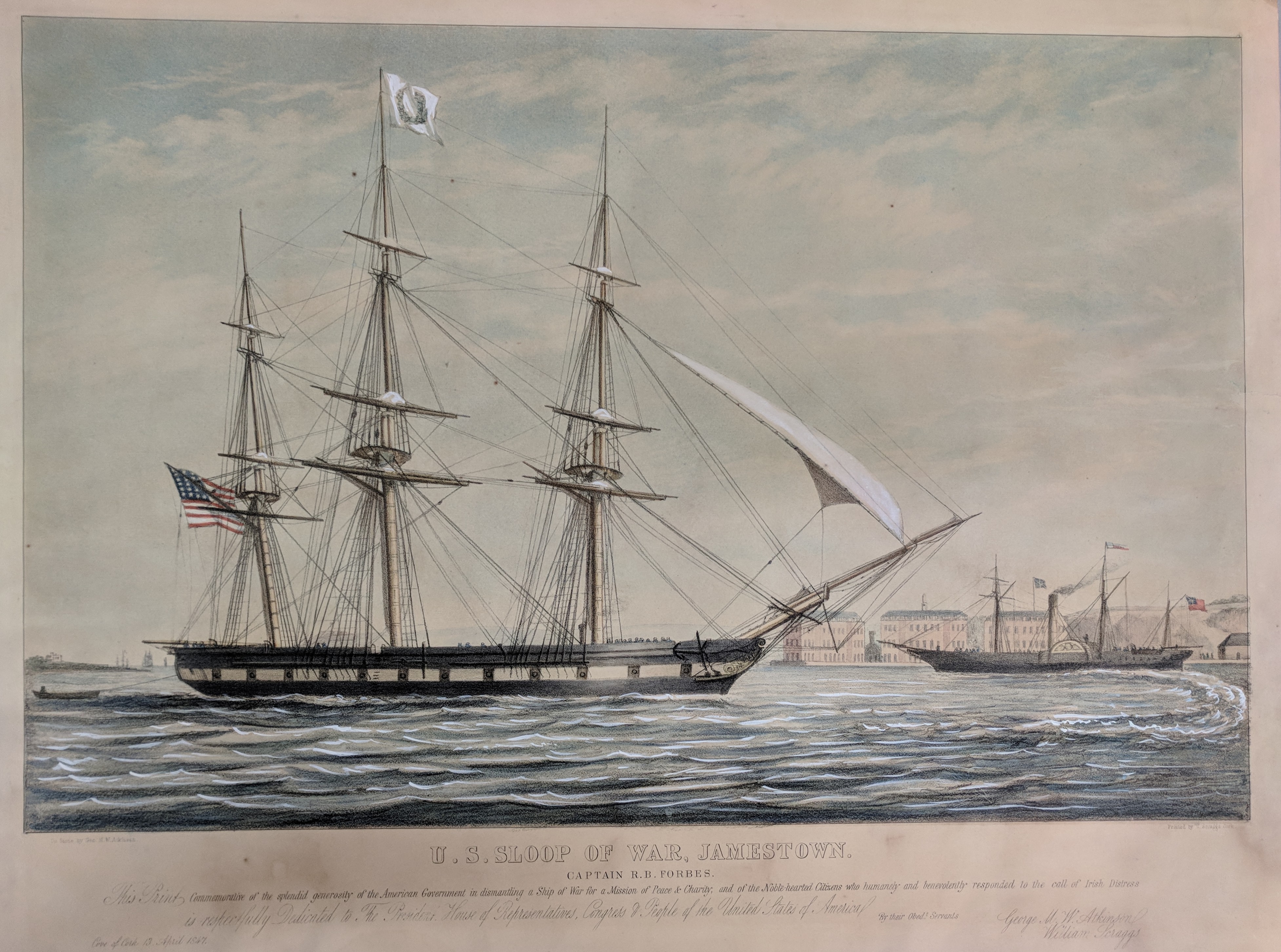

He spent a few months at the Naval Academy and by March 1851 was stationed aboard the sloop USS Jamestown. In May, Thorburn requested to be attached to the USS Susquehanna in order to study steam propulsion. Apparently this request was granted because I found him listed in the ship’s muster rolls from September 1851 through February 21st, 1852 when he transferred to the USS Marion. He was back at the Naval Academy in October of 1852, possibly to take his exams, because in 1854 he is noted as being a “passed midshipman” on the steam frigate USS Saranac in the Mediterranean.

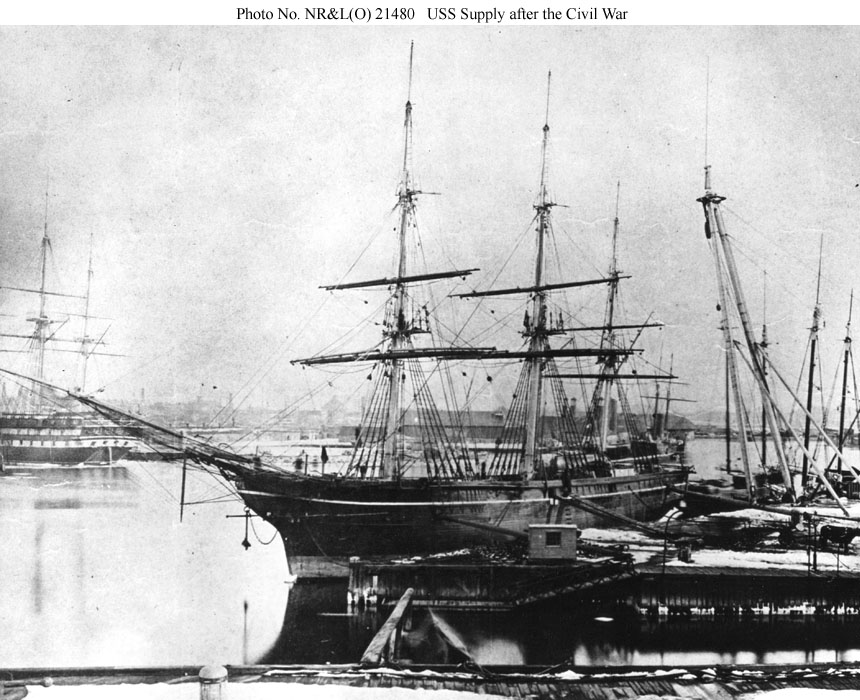

On September 15, 1855, while still stationed on board Saranac, Thorburn was promoted to lieutenant. Although the US Navy Register doesn’t place him on board until 1857, Thorburn transferred to the US Navy store ship Supply, possibly in late 1855 or early 1856 as Thorburn’s name appears in court martial documents of the USS Susquehanna and USS Supply dated September 9th, 1856 and October 17th, 1856.

During this time period, Supply was carrying out a fascinating mission. In July/August of 1855 Supply’s commander, Lt. David Dixon Porter and Major Henry C. Wayne of the Quartermaster’s Department were dispatched by the Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis, to travel the Levant and acquire camels for the War Department. The camels were required for an experiment to determine whether the animals might be useful in exploring the arid western frontier which was inaccessible by water and other transportation methods. With little or poor-quality water and food available most animals wouldn’t survive. The camel’s ability to carry heavy loads under the most arduous conditions was considered to be a possible solution to the problem.

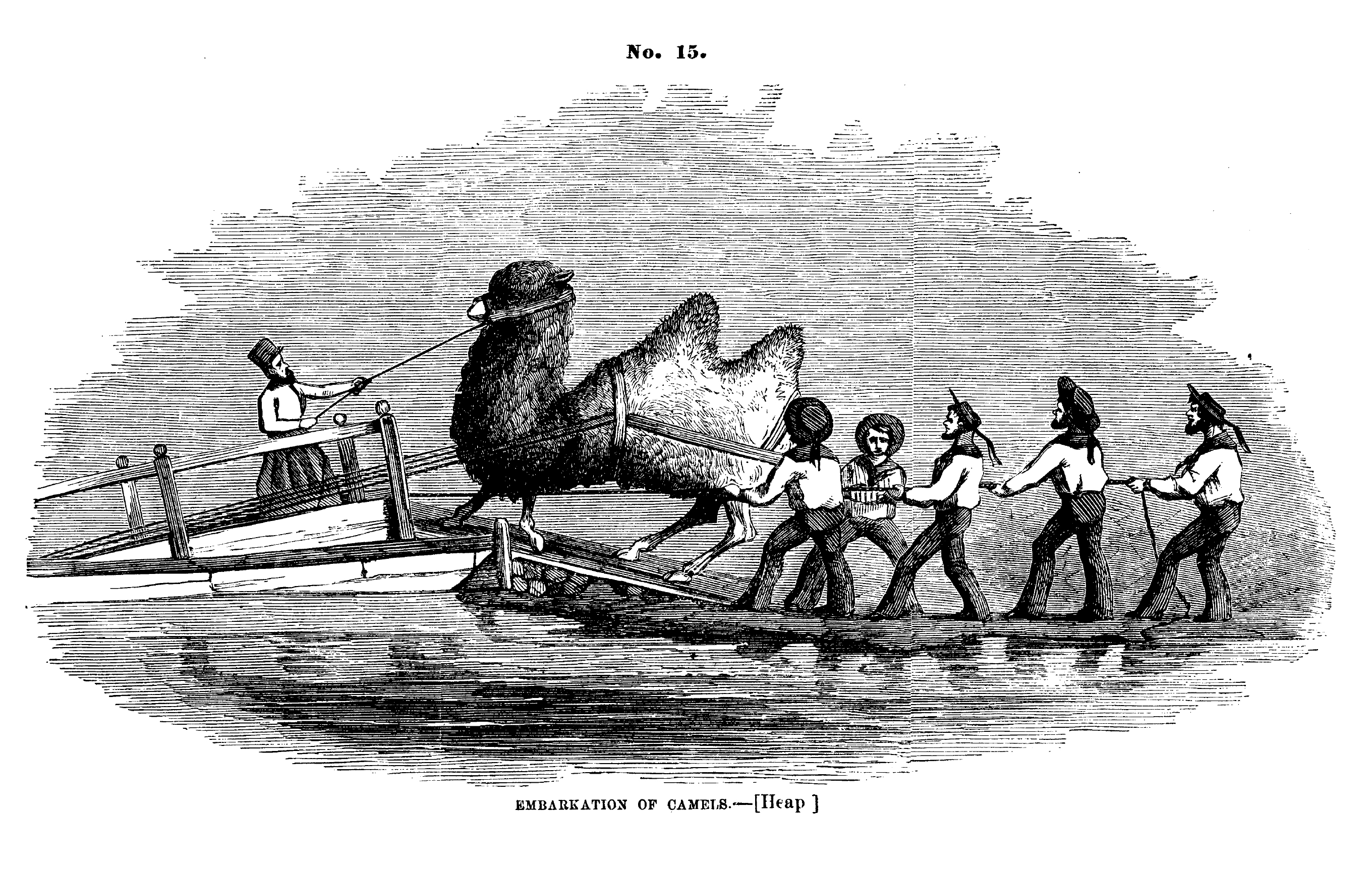

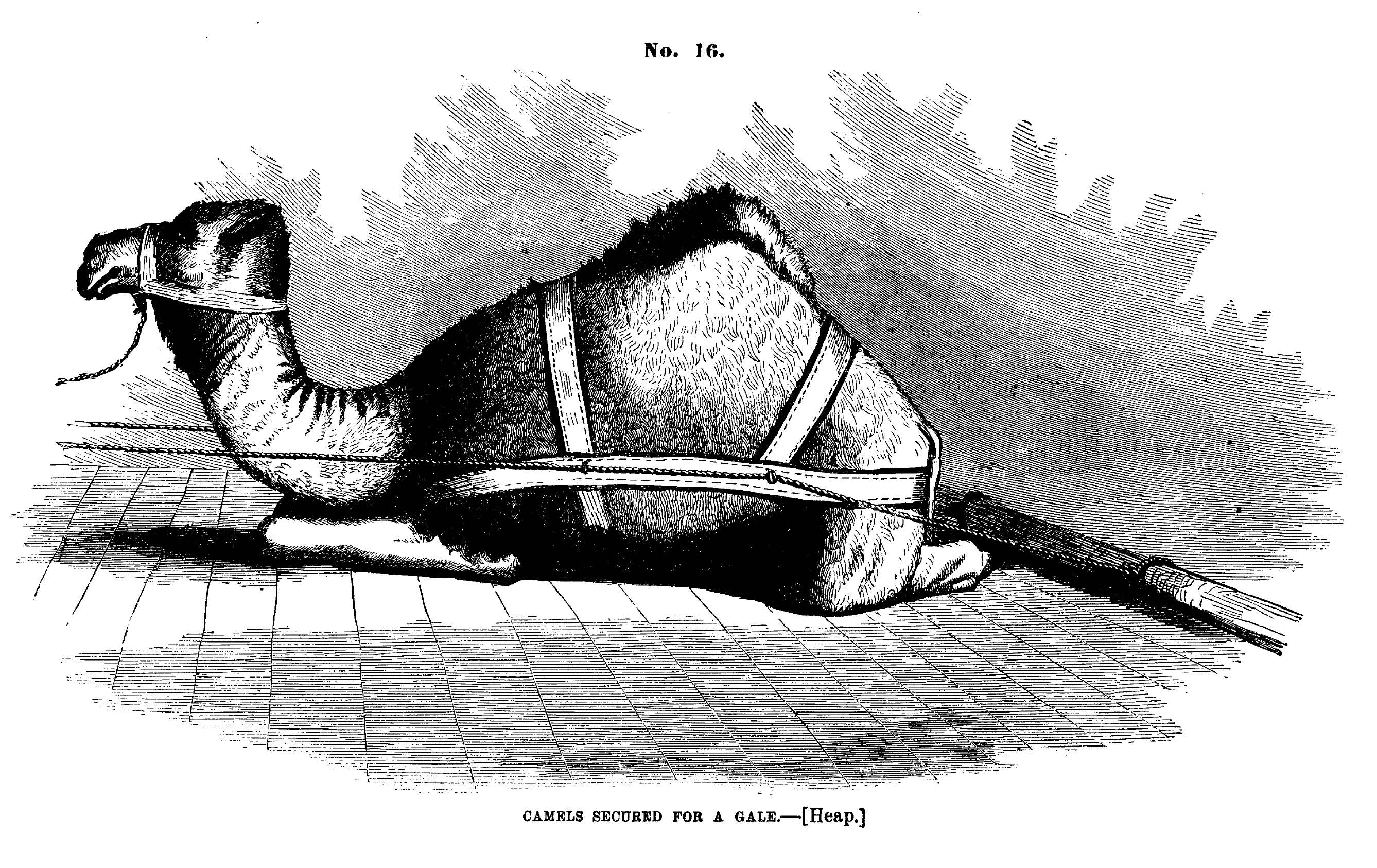

Supply arrived in Tunis on August 4, 1855 and within a few days Porter and Wayne had acquired their first camel. When the Bey of Tunis learned of the experiment, he sent two more camels from his private herd. Porter and Wayne spent the next few months learning everything they could about the animals and how to care for them. In December they acquired nine more camels in Egypt and twenty-one more in Smyrna including four “wrestling” camels and one “Tulu,” a female camel weighing more than 2,000 lbs and standing 7’4” high. The camel was so big Porter was forced to cut away part of his main deck overhead to accommodate the camel’s hump!

On February 15, 1856 Supply left Smyrna loaded with thirty-three camels and headed for the Texas coast. They did make some stops along the way including one in Jamaica and during their stay 4,000 people visited the ship to see the camels. Supply reached Indianola, Texas on May 14, 1856 and landed the camels while a crowd of several hundred spectators watched. The camels were later moved to corrals about 60 miles from San Antonio (Camp Verde was established by the US Army to house its camels on July 8, 1856). While they were still unloading, Porter was directed by Davis to head back to the Mediterranean to acquire more camels. In February 1857 Porter and the Supply were back in Texas with forty-one more camels.

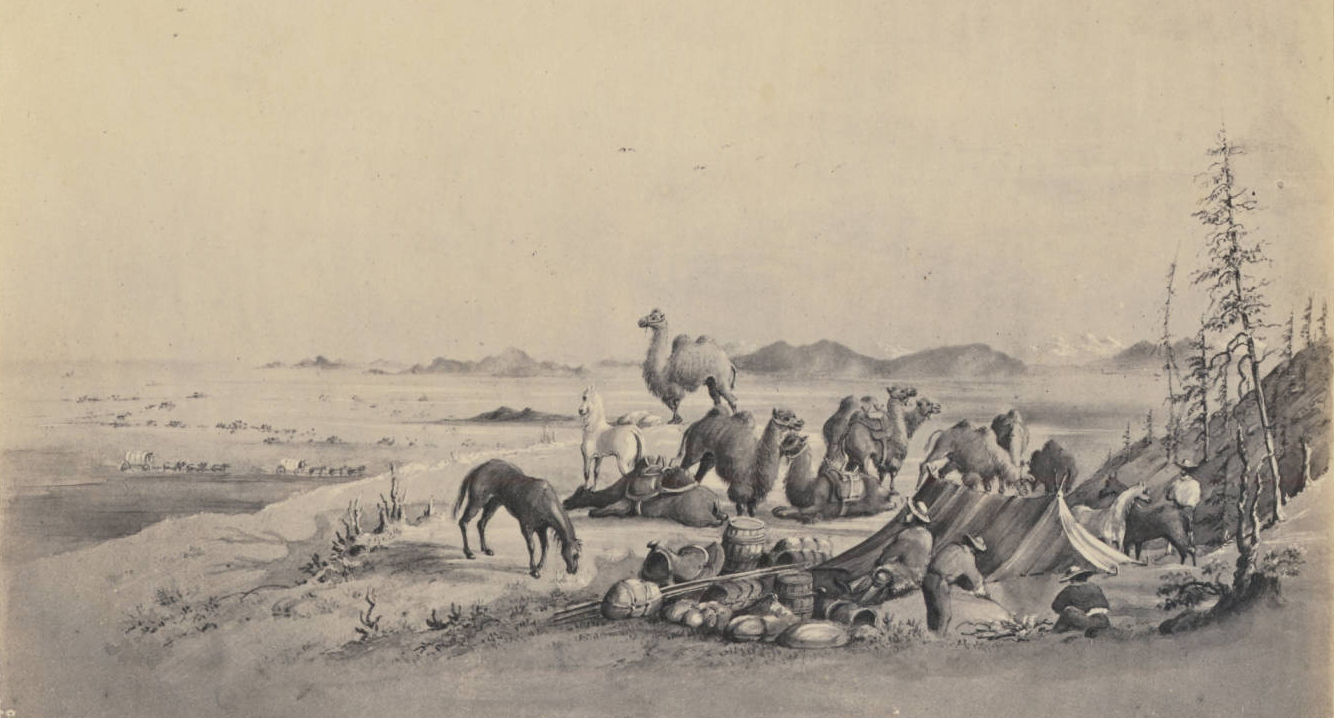

Around the same time, President James Buchanan appointed former US Navy lieutenant Edward Fitzgerald Beale as superintendent of a government survey to establish a military road from the New Mexico Territory to California. Along with his equipment and men, Beale was told to take twenty-five camels to determine their usefulness as pack animals. He was accompanied on this venture by his cousin and an old naval friend, Lt. Charles E. Thorburn (and possibly a relative as Thorburn’s half sister was married to a man named Beale). This is corroborated by the 1858 US Navy Register which states that Thorburn was on “Special Duty under the War Department.”

On June 6, 1857 the three men arrived in Indianola, Texas and organized their wagon train. They then headed to San Antonio so Beale could acquire their complement of camels from nearby Camp Verde. The expedition left San Antonio on June 25th and headed west for the New Mexico territory. By July 17th they had reached Fort Davis and ten days later they had reached Fort Bliss. Beale was impressed by the camel’s endurance and noted that they “could travel continuously in a country where no other barefooted beast could last a week.”

The expedition made its way north up the Rio Grande to Albuquerque. After a brief stay, they headed to Fort Defiance (today that’s near Window Rock, Arizona) arriving on August 15th. Leaving again on August 27th the replenished their supplies at Zuni and continued their trek across the Arizona territory. The expedition reached the Colorado River on October 17th. They crossed the Colorado, losing two horses and ten mules in the process, but the camels easily swam across the broad river. The expedition wrapped up in Los Angeles on November 9, 1857.

At that point Beale sent Thorburn to Washington with the expedition’s notes and astronomical observations so that he could prepare a map of the expedition’s route. He also sent correspondence for the Secretary of War, the Hon. John B. Floyd, in which he commends Thorburn with the following words:

“In closing this report, I desire to say a word, in conclusion, of the officer who bears it. His reputation in his own service would render unnecessary any commendations of mine, but the department of which you are the head, being unacquainted with his merits, I desire to make them known to you. He has evinced on this journey an activity, zeal, intelligence, and courage, rarely to be found combined in any one man, and has been to me, not only a most able assistant, but an agreeable companion throughout the entire exploration…”

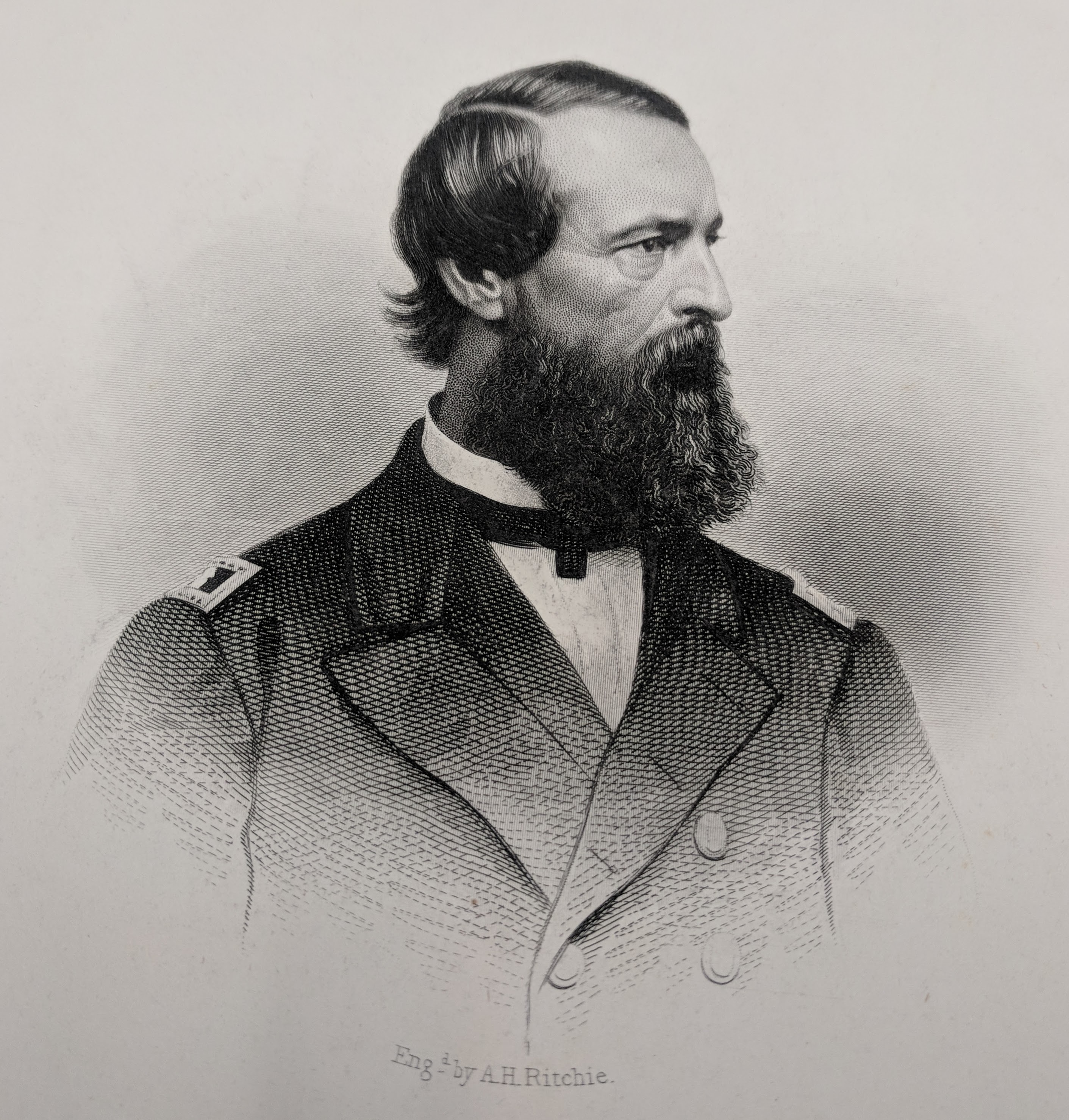

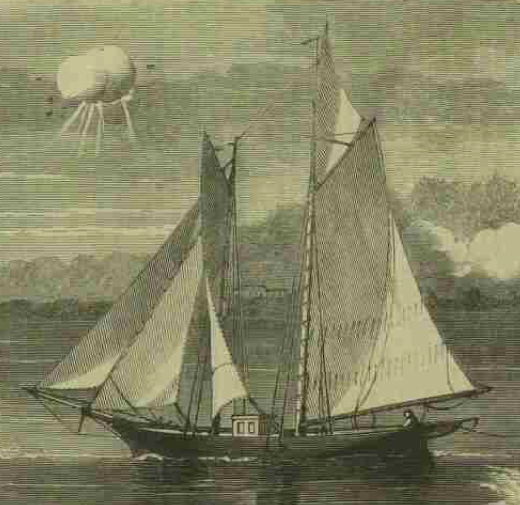

Lt. Thorburn was detached from the War Department in May 1858 and within days had accepted an assignment aboard the US Navy schooner Fenimore Cooper under the command of Lt. John Mercer Brooke. Brooke had been commissioned to survey a steamship route between San Francisco and Hong Kong and map the topography of the sea floor of the north Pacific Ocean (to determine if reefs, shoals or islands identified as dangers to navigation on many charts existed or not). Brooke was also told identify any islands that might provide a rich source of guano.

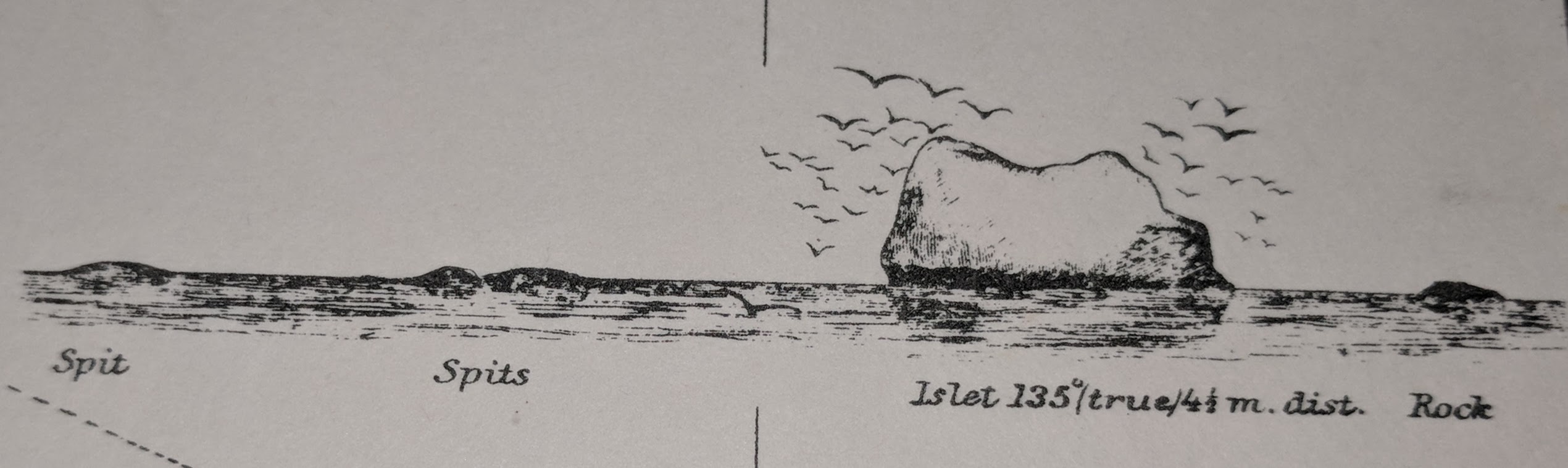

The expedition left San Francisco on September 26, 1858 and surveyed the route to the Hawaiian Islands. Brooke spent several months surveying the islands including the Leeward Islands from Nihoa to Lisianski. On January 3, 1859, Brooke sent Lt. Thorburn and Edward M. Kern (the expedition’s artist) ashore to study La Perouse Pinnacle at French Frigate Shoal. They acquired guano specimens, turtles, albatross, echinus, shells, eggs, and seeds and nuts to help “afford a clue of the general course of the winds and currents.” Noting that the island held a rich guano deposit Brooke sent Thorburn back to the island the following day to formally claim it as a possession of the United States. Thorburn accomplished this task by climbing to the top of La Perouse Pinnacle (which was covered by more than four FEET of bird poop so I bet he smelled FANTASTIC when he got back!) and mounting a board documenting US claim to the island.

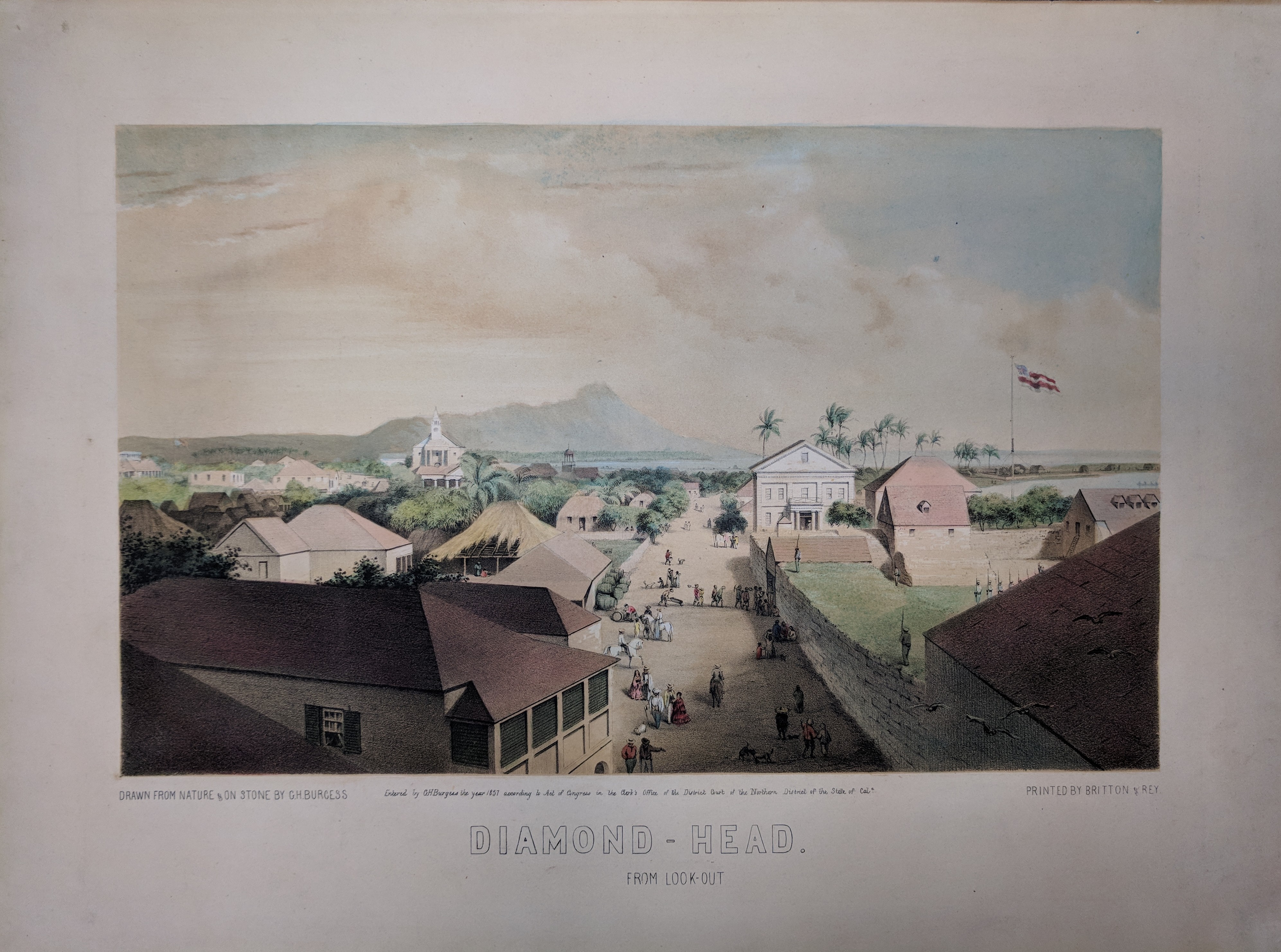

Spending so much time in and around Hawaii interacting officially and socially with the civilian population increased the voyage’s diplomatic importance. Not having much experience in diplomacy Brooke relied heavily on Thorburn, who could speak French, Spanish and Italian and had served as an “aide” in the Mediterranean. Their diplomatic mission reached its high point in February 1859 when Brooke, Thorburn and Kern had an audience with King Kamehameha IV.

On March 5th the voyage continued westward. While anchored in Guam a tropical cyclone caused the ship to drag its anchors repeatedly and it was only the quick action of Thorburn (Brooke was ashore at the time) that prevented the Fenimore Cooper from being grounded on a nearby reef. Unfortunately this wouldn’t be the ship’s last brush with bad weather. They spent several weeks in Hong Kong and explored many of the islands south of Japan before anchoring in Kanagawa Bay on August 13, 1859.

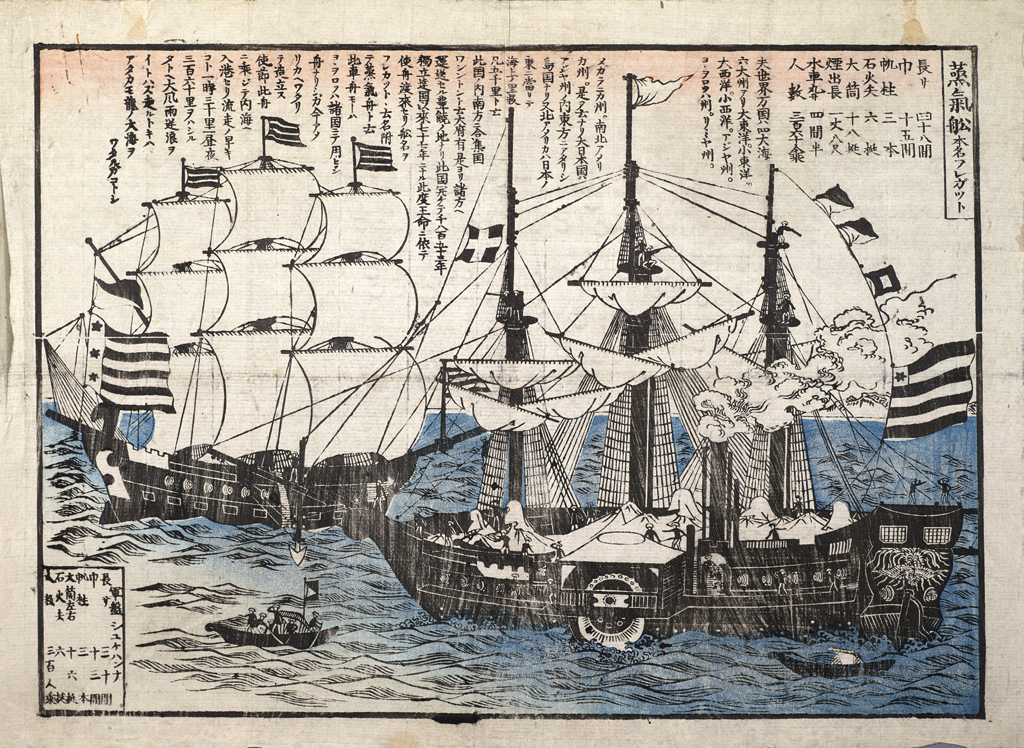

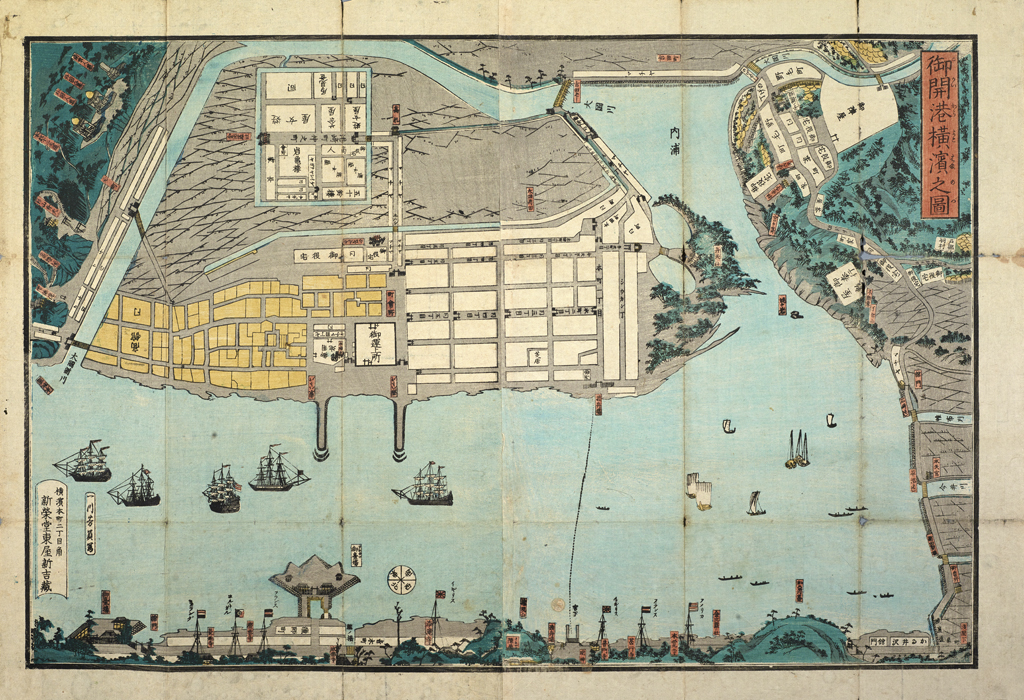

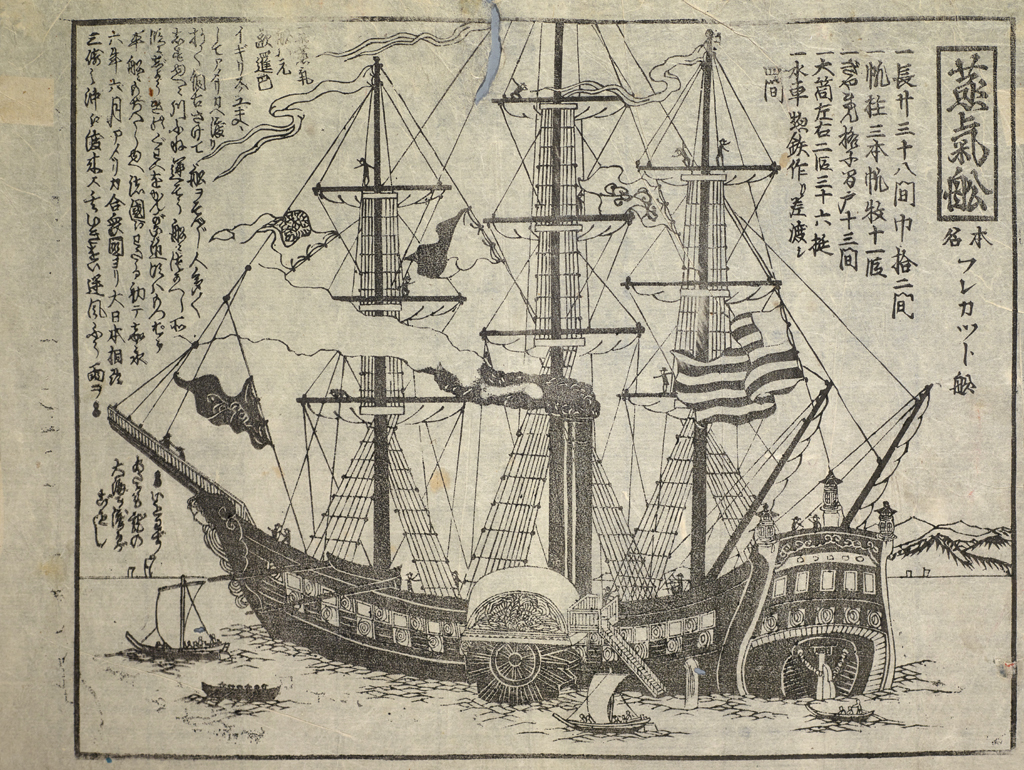

A few days later Brooke and Kern left Thorburn in charge of the ship and traveled to Tokyo to meet with the US consul general Townsend Harris. On the 23rd a typhoon forced Thorburn run the ship aground in order to save the men who remained on board and all of the instruments and records produced during the expedition. With the help of the Japanese and Russians (who respected Brooke because of his attempts to save the life of an officer who had been attacked by angry samurai) they were able to salvage everything from the vessel. Unfortunately, a survey showed the ship to be so rotten it was sold out of US Navy service leaving her twenty-one crew stranded in Yokohama. They were given temporary lodgings originally built for foreign merchants by the Bakufu (Japan’s military government) until a US Navy ship arrived to carry them home. Just one month later marked the start of a most interesting time in Japan’s history–the gold rush of 1859.

After Townsend Harris’ Treaty of Amity and Commerce (the treaty that formally opened the Japanese Empire to trade with the United States) went into effect on July 4th, 1859 it sparked a problem with currency exchange in Japan. At the time, silver was seriously overvalued by the Japanese government (they owned the most productive silver mines and made a lot of money through currency debasement). Foreign merchants who could obtain Japanese silver coins (ichibu) could exchange them for Japanese gold coins (cobangs) at a five-to-one ratio. Everywhere else, the ratio of silver to gold was 15 to 1 which meant the Japanese gold could be shipped out the country and exchanged for a quick profit of anywhere from 40% to 150%.

The article “Yokohama Boomtown, Foreigners in Treaty-Port Japan (1859-1872)” by John W. Dower on MIT’s Visualizing Cultures website offers a great description of this print. “Complete Picture of the Newly Opened Port of Yokohama,” pieced together from eight oversize sheets of paper—is one of the largest composite prints ever issued in Japan. Published shortly after the port opened, it literally served as a map of the entire area. One sees here not merely the foreign settlement and two piers that the Bakufu had built, but also the adjoining Japanese district, the open fields beyond, and—an entirely separate enclave—the entertainment quarters that catered to foreigners as well as Japanese. The entire new city was surrounded by water—harbor in front and canals at the side and back—thus enabling the Bakufu to monitor the movement of people in and out. The artist’s vantage-point was a village near Kanagawa on the opposite shore. The Tōkaidō highway that the Bakufu worried about runs along the bottom of the print.

Sitting on the sidelines as the rush began was a penniless and in debt Lt. Charles Thorburn. When the USS Powhatan arrived in Yokohama on October 3 Lt. Thorburn lost no time in approaching Commodore Josiah Tattnall with a plan intended to take advantage of the situation. Thorburn suggested that Tattnall take the Powhatan to Shanghai and acquire Mexican silver dollars (legal tender throughout most of the world in 1859), return to Yokohama where as many of the silver dollars as possible would be exchanged for Japan’s devalued gold, and then sail to Hong Kong where the gold could be sold at its higher world market value.

Interestingly, Commodore Tattnall seems to have approved of Thorburn’s plan because he quickly reorganized Powhatan’s voyage back home in order to do as Thorburn suggested. Powhatan returned from Shanghai on October 31 with about 500,000 Mexican silver dollars and Thorburn immediately went to work. First, he convinced the governors of foreign affairs to exchange the Mexican dollars for 150,000 Japanese silver coins in one lump sum (normally there were strict limits placed on the number of coins that could be exchanged daily) and then he frantically worked to exchange the silver coins for gold ones (cobangs). When the supply of cobangs dried up he used the remaining 60,000 ichibu to buy Japanese goods (which were actually turning over an even higher profit than the gold). It may have been at this point that Thorburn acquired our beautiful little clock. Thorburn then chartered the schooner Colneria L. Behan to transport the cargo to the United States.

I don’t know how any of the other officers aboard Powhatan fared, but John M. Brooke stated that Thorburn told him he had made a profit of $9,000 in the month or so the trade was going on–not too shabby for someone who started out in debt!

When one of Powhatan’s lieutenants (Alexander W. Habersham) resigned his commission in order to expand his commercial business in Japan, Tattnall appointed Thorburn to fill the post. On February 13 Powhatan, with a now “wealthy” Thorburn on board, began its historic voyage to bring the Tokugawa government’s first diplomatic mission to the United States to ratify the Treaty of Amity and Commerce. This would be Thorburn’s last voyage as he resigned his commission on June 24, 1860.

USS Powhatan, which carried the first Japanese embassy to San Francisco and Panama in 1860. (Accession# 1963.0040.000006/LE 2888)

If you’re interested in learning more about some of the events Lt. Charles Thorburn played a role in check out these resources:

- Uncle Sam’s camels; the journal of May Humphreys Stacey supplemented by the report of Edward Fitzgerald Beale (1857-1858) edited by Lewis Burt Lesley.

- John M. Brooke’s Pacific Cruise and Japanese Adventure, 1858-1860, by George M. Brooke

- “The Japanese Gold Rush of 1859”, by John McMaster, The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 19, No. 3 (May, 1960), pages 273-287.

- The Shogun’s Gold: A Novel of 19th Century Intrigue, by Masayoshi Satō

- Lieutenant David Dixon Porter and His Camels, by Commander Malcolm W. Cagle, USN, Proceedings Magazine, December 1957, Vol 83/12/658