Tensions were rising throughout the South during the first week of April 1861. While the Upper South had yet to join the Confederacy, the Lincoln administration was alert to the threatening war clouds and the possibility of states, like Virginia, leaving the Union. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles recognized that Gosport Navy Yard and the steam screw frigate USS Merrimack were tempting targets for pro-secessionist Virginians. Accordingly, on April 10,1861, Welles advised Gosport Navy Yard commandant Flag Officer Charles Stewart McCauley that he must show great vigilance in protecting the yard. He stated that it was important that one of the US Navy’s most modern warships, Merrimack, be repaired and moved to another navy yard. Welles added that McCauley was to do nothing to upset the Virginians and to use his best judgment in discharging his duties to protect Gosport. Welles concluded, it is “desirable that there should be no steps taken to give needless alarm.”

Merrimack Readies for Sea

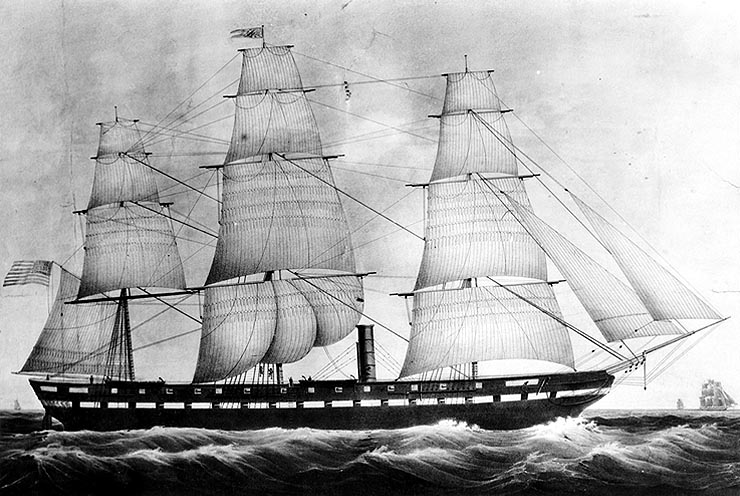

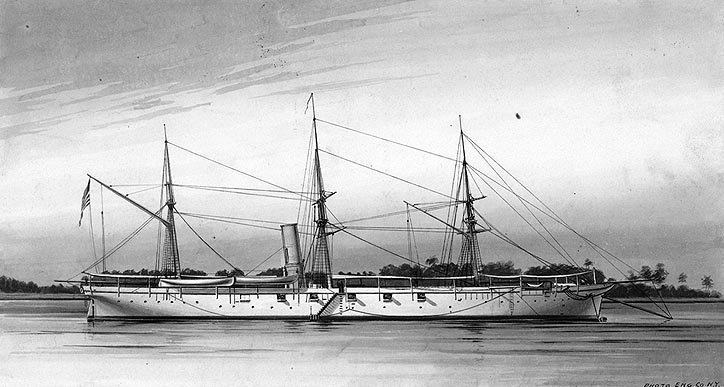

Gosport’s commandant responded by telegram on April 11, stating that it would take a month to revitalize Merrimack’s dismantled engines. Welles was shocked by McCauley’s reply, calling the yard commandant “feeble and incompetent for the crisis.” He sent US Navy’s chief engineer, Benjamin Franklin Isherwood, to Gosport to prepare Merrimack for sea. Isherwood estimated that it would take him a week to rework the ship’s engines. Commander James Alden was ordered to accompany Isherwood and assume command of the frigate. They arrived at Gosport Navy Yard on April 14, 1861. Isherwood immediately set to work restoring Merrimack’s machinery.

Welles continued to pressure McCauley from afar to preserve Navy property at Gosport. On April 16, Welles ordered McCauley: “no time should be wasted in getting her (Merrimack’s) armament on board.” Welles concluded his letter with the admonition that the”vessels and stores under your charge you will defend at any hazard, repelling by force, if necessary, any and all attempts to seize them, whether by mob violence, organized effort, or any assumed authority,”

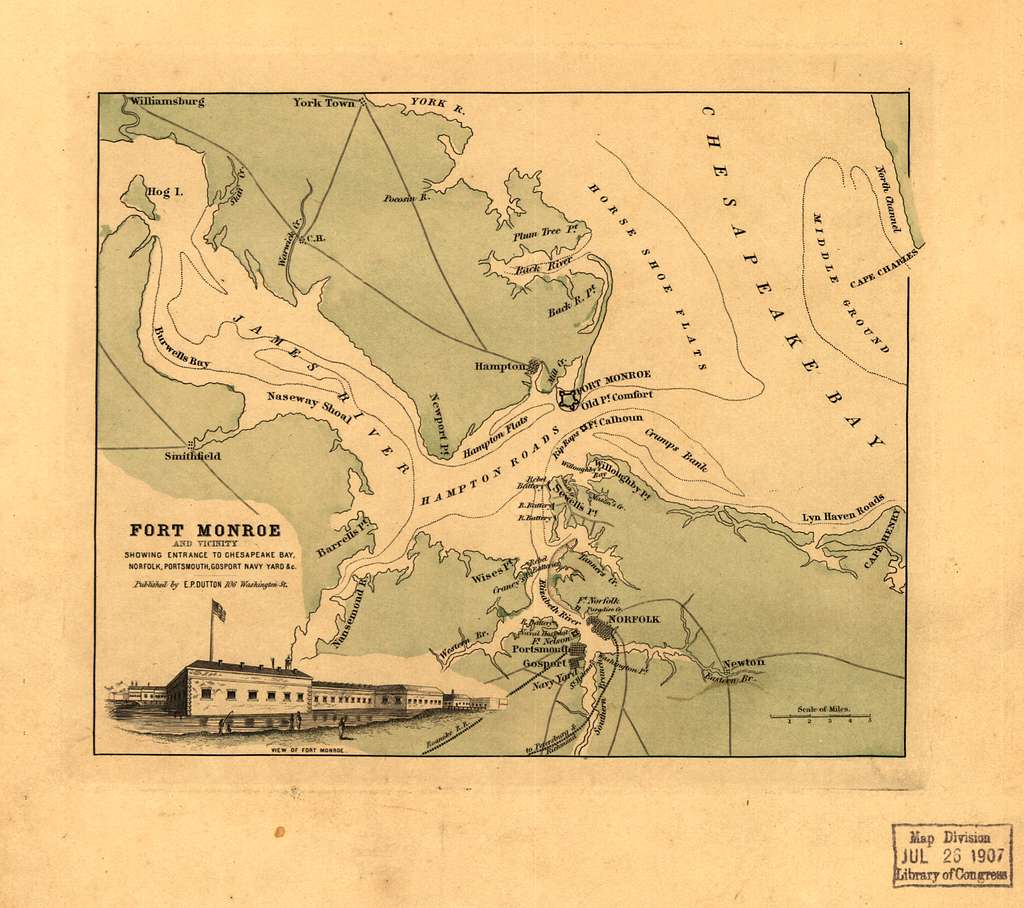

Map of Fort Monroe and vicinity showing entrance to Chesapeake Bay, Norfolk, and Portsmouth, VA, ca. 1861. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

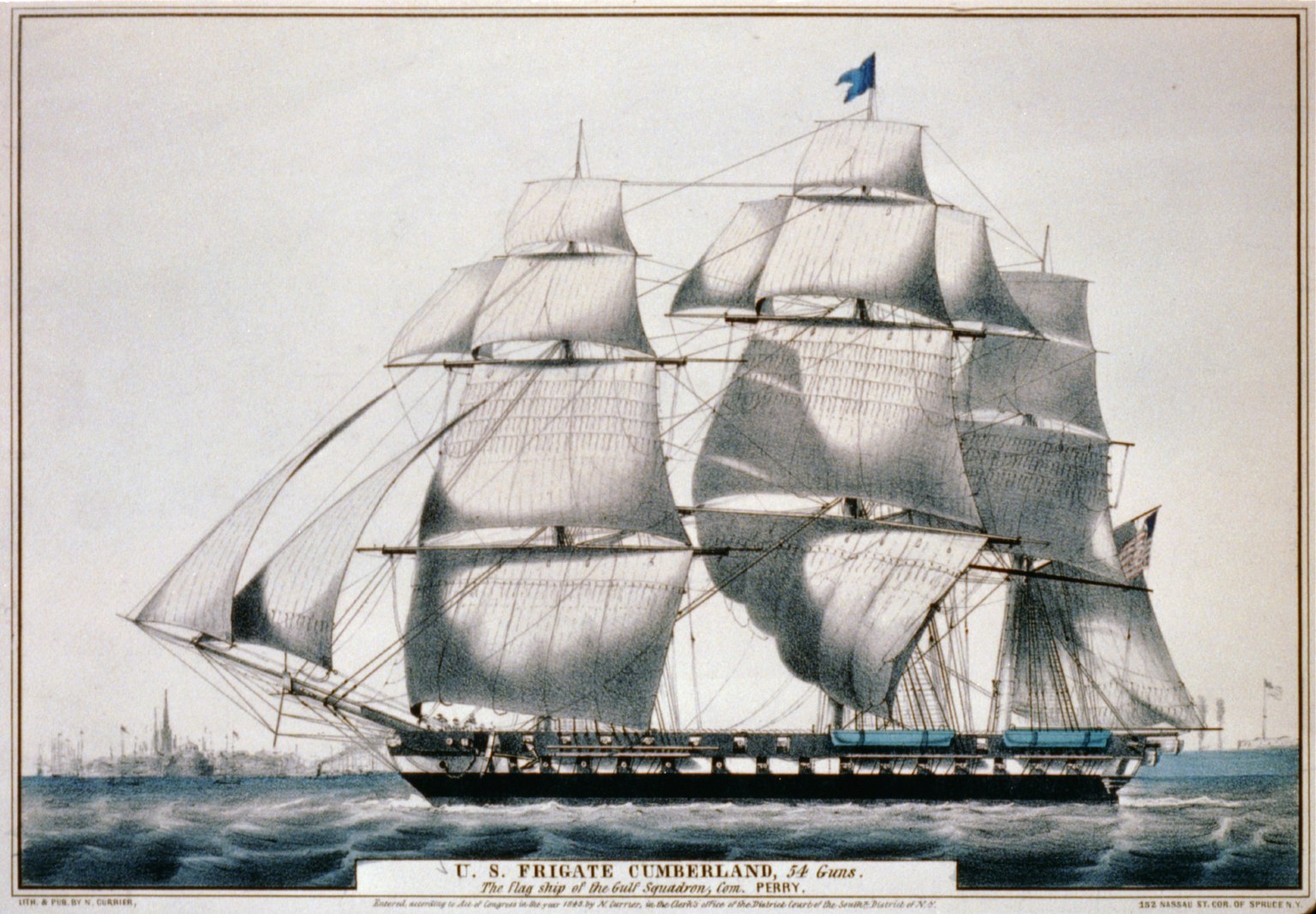

With war already at hand following the fall of Fort Sumter, Welles was very concerned about the US Navy’s impending need to enforce a blockade of the Southern coastline. Welles recognized that he required every available vessel to interrupt the flow of commerce into Southern harbors. Since Merrimack was one of only five first-class steam frigates in the US Navy, the secretary of the navy demanded that the warship be taken “beyond the reach of seizure.”

Reinforcements Arrive

Simultaneous with his missive to McCauley, Welles reiterated in a letter to Cumberland’s commander Garrett Pendergrast that the sloop must stay at Gosport because “events of recent occurrence and the threatening attitude of affairs in some parts of our country, call for the exercise of great vigilance and energy at Norfolk.”

Pendergrast positioned Cumberland just off Gosport. This meant that the sloop’s firepower could now be used to either effectively defend the yard or to cover the release of ships so they could be transferred to safer havens. Besides Merrimack, the only other warships considered in good enough condition to warrant removal were: Dolphin, Germantown, and Plymouth.

Pendergrast, however, left the yard’s defense in McCauley’s hands. Other than Cumberland, the commandant had considerable resources available to organize some type of defense. Even though the 120-gun Pennsylvania was stuck in the mud, and serving as a receiving ship, it was still armed with a full complement of cannons. So Pennsylvania could be used as a stationary battery, adding the weight of its broadside to that of Cumberland.

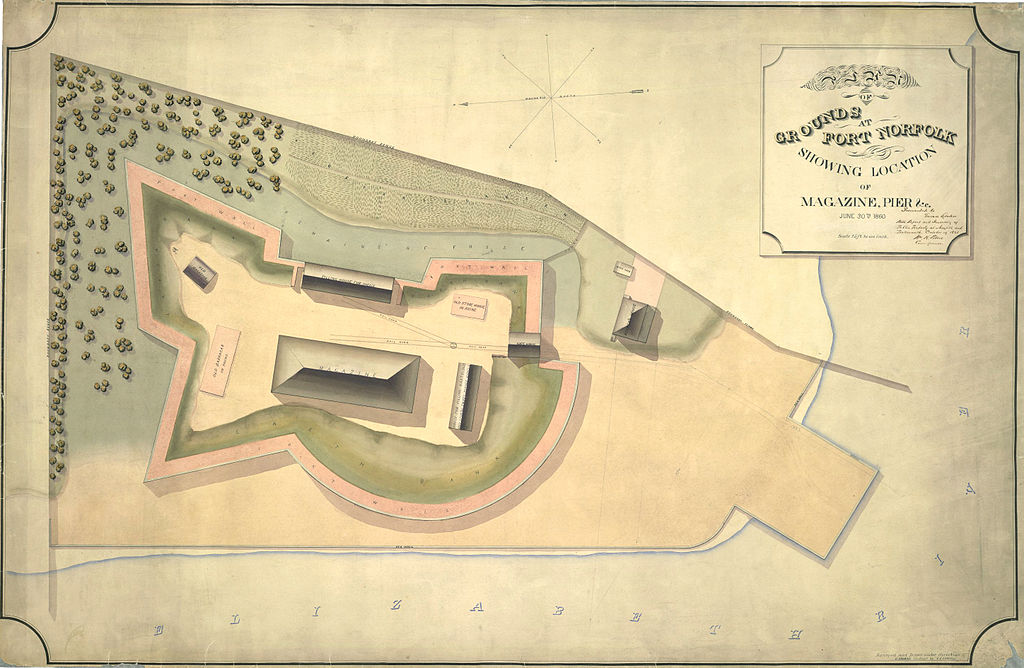

Despite the suspected loyalties of many of McCauley’s officers, approximately 600 marines and sailors were apparently ready to follow McCauley’s commands. The yard contained an abundant supply of ammunition and weapons to arm these men. Gosport also featured a considerable defensive perimeter consisting of an eight-foot-high land face brick wall and the Elizabeth River. Instead of organizing these resources or supporting the removal of vessels, McCauley believed he was sitting on a powder keg that could force Virginia into war. He remained passive as events headed toward an explosive conclusion.

Virginia Leaves the Union

President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers following the fall of Fort Sumter on April 15, prompted Virginia to secede from the Union on April 17, 1861. Hampton Roads immediately became a major flashpoint. Virginians clamored to secure Federal property, which they believed to rightly belong to the commonwealth. Gosport appeared ripe for conquest.

Merrimack Retained in Port

Meanwhile, Benjamin Isherwood completed the emergency repairs to Merrimack on April 17, and reported to the yard commandant that the frigate would be ready to leave port the next day. On the morning of April 18, Isherwood had steam in the ship’s boilers, and the jury-rigged engines seemed capable of taking the vessel at least as far as Fort Monroe. McCauley, however, advised Isherwood and the ship’s commander, James Alden, that he had decided to retain the frigate in port. McCauley was the ranking officer so they had little choice but to concede to the commandant’s command. Merrimack’s fires were banked, and the two men immediately left for Washington to explain to Secretary Welles why the frigate had not left port.

McCauley’s indecision was caused by several factors. The commandant’s actions were tempered by his initial interpretation of Welles’s April 10 command: “there should be no steps to give needless alarm.” Welles’s order of April 16, instructing McCauley to remove all property from Gosport only added to the commandant’s confusion. His decisions, or lack thereof, were further influenced by the many pro-Southern officers on his staff. McCauley’s leadership during the hour of crisis at Gosport was questioned by many pro-Union officers. They believed that the yard commandant was drinking heavily, which made him suspect and an impediment to the US Navy’s goals.

Virginians Demand Control of Gosport

As the Federals struggled with McCauley’s procrastinations, local Southern firebrands were rapidly organizing their own effort to secure the yard. Virginia’s secession galvanized nearby communities into action. A Vigilant Committee was established, while militia troops mustered in Portsmouth and Norfolk. The committee sank several merchant ships in the channel off Sewell’s Point to block Federal access to the navy yard. It was rumored to be building “masked batteries” from which to shell the yard.

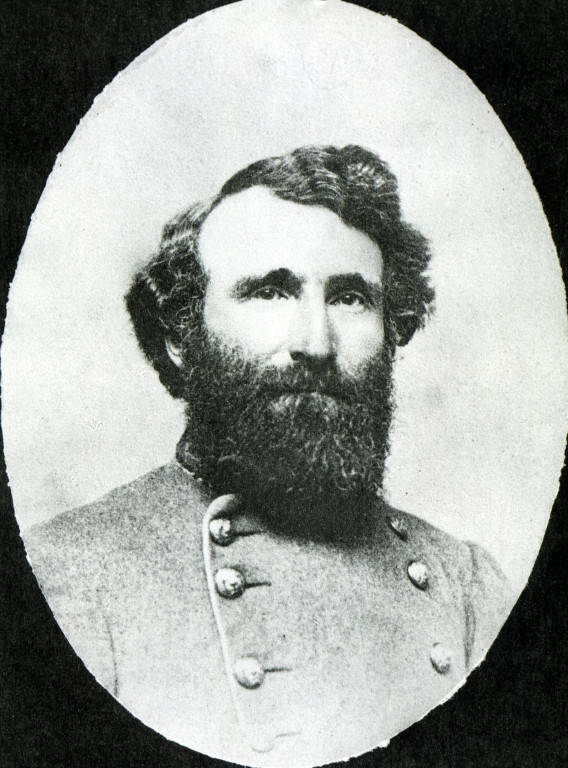

On April 18, 1861, Governor John Letcher ordered Major General William Booth Taliaferro of the Virginia Militia to assume command of troops assembling in the Norfolk area. Letcher also appointed Robert B. Pegram as a captain, and was instructed to “assume command of the naval station, with authority to organize naval defenses, enroll and enlist seamen and marines, and temporarily appoint warrant officers, and to do and perform whatever may be necessary to preserve and protect the property of the commonwealth and the citizens of Virginia.”

Taliaferro arrived in Norfolk on the evening of April 18. The next morning, he began organizing his meager resources of local militia units. Two artillery batteries ﹘Norfolk Light Artillery Blues and Portsmouth Light Artillery ﹘ were available. However, these companies could only muster a combined firepower of eight cannons; the largest was a 12-pounder. Although his command only numbered about 850 men, Taliaferro immediately opened aggressive negotiations with Flag Officer McCauley.

Taliaferro, a Mexican War veteran and former member of the Virginia House of Delegates, advised McCauley that he planned to assume possession of the Gosport Navy Yard on behalf of the sovereign state of Virginia. When McCauley refused to concede, Taliaferro requested more troops be sent to Portsmouth from South Carolina so Gosport could be taken by assault. Rumors prevailed throughout the yard about the impending arrival of more Southern soldiers. To further intimidate McCauley, William Mahone, a Virginia Military Institute graduate and president of the North & Petersburg Railroad, began running trains in and out of Norfolk and Portsmouth. When the trains came into town, they were filled with yelling citizens to create an illusion of massive troop arrivals.

A Relief Expedition is Organized

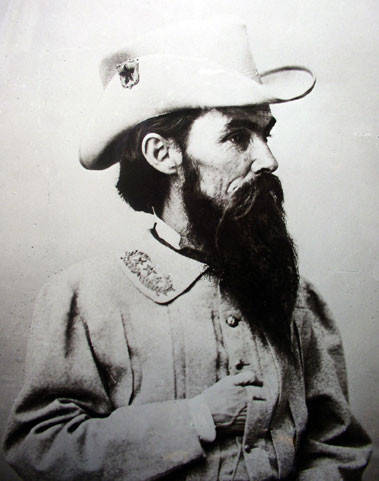

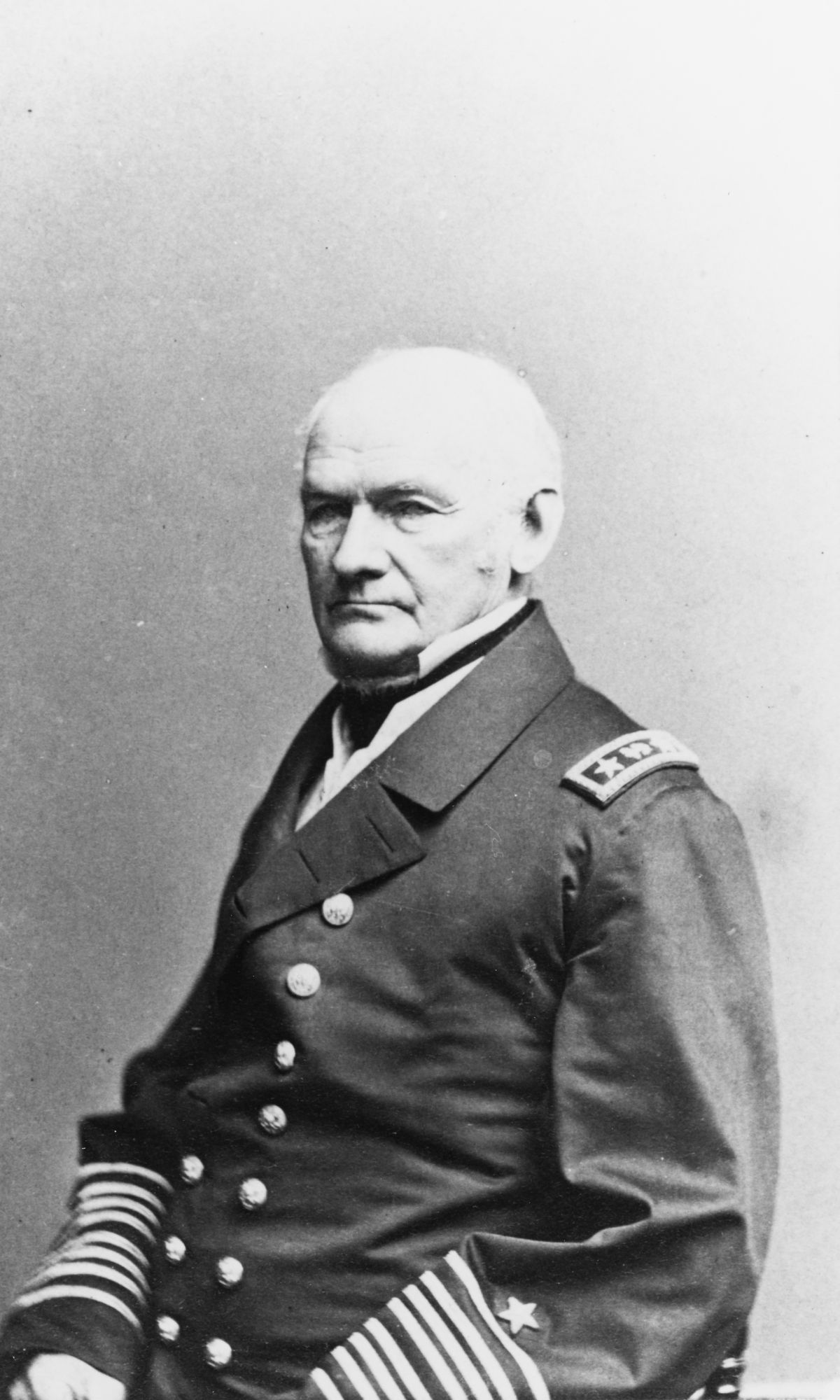

When Merrimack failed to leave Gosport on April 18, Gideon Welles realized that a more resolute action was required. Welles dispatched Flag Officer Hiram Paulding, a 50-year Navy veteran, and the most senior officer in the US Navy, on board the eight-gun steamer USS Pawnee. Filled with explosives, Pawnee had 100 marines, ready to take command at Gosport. Unfortunately, Welles did not advise McCauley about Paulding’s relief force.

As Paulding prepared his command to leave Washington for Gosport, McCauley became increasingly unnerved by the events unfolding around him. The pro-Southern citizenry was in a bellicose mood and gathered outside the yard’s gates demanding access. The Virginia Militia continued its game of nerves, hoping to hoodwink McCauley into handing over an intact facility to the commonwealth. Even though the yard’s commandant rejected the demands, he feared that the newly constructed batteries and obstructions at the mouth of the Elizabeth River limited his options. Indecision racked McCauley’s brain as to what course to take.

This is part two of a four-part series by John Quarstein about Gosport Navy Yard.

Excerpted from CSS Virginia: Sink Before Surrender, John V. Quarstein. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2012. Available in the Museum’s Web Shop: https://www.google.com/url?q=https://shop.marinersmuseum.org/sink-before-surrender-pb.html&sa=D&source=hangouts&ust=1587055613966000&usg=AFQjCNGlDlDHoLEWTXRLO71bPBmtARqV5A