Earlier this year, Collections Manager Jeanne Willoz-Egnor posted about the Museum’s newly acquired gut skin parka.

In addition to establishing provenance and the cultural significance of this incredible object and the people who made it, the Museum was interested in learning more about the specific materials used to create the parka. This information adds to our understanding of how the parka was made and used and the unique story of its life. And as Jeanne pointed out, identifying the materials present had pretty important legal implications in the process of its acquisition!

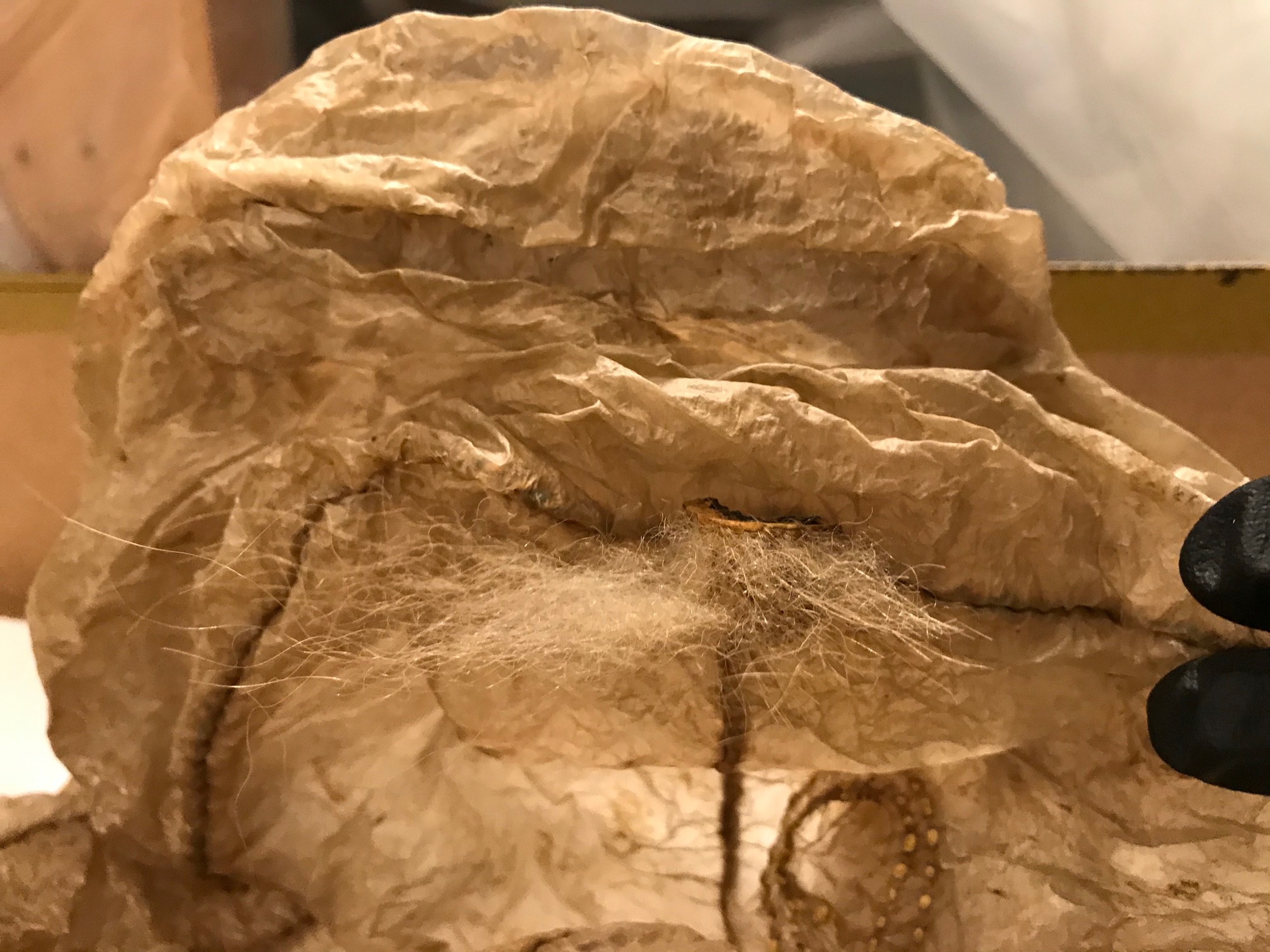

Once the parka was at the Museum, I was able to begin a thorough investigation of the materials. This included analysis of the various fibers used for the stitching, the gut itself, and a feature that was particularly hard to notice before the parka was at the museum: a patch of skin and fur at the top of the hood. Decorative patches of fur are typical of Iñupiaq parka ornamentation, and could be from a wide range of mammals. While there was some speculation about the type of fur on this parka based on macroscopic features, we wanted a more conclusive identification if possible.

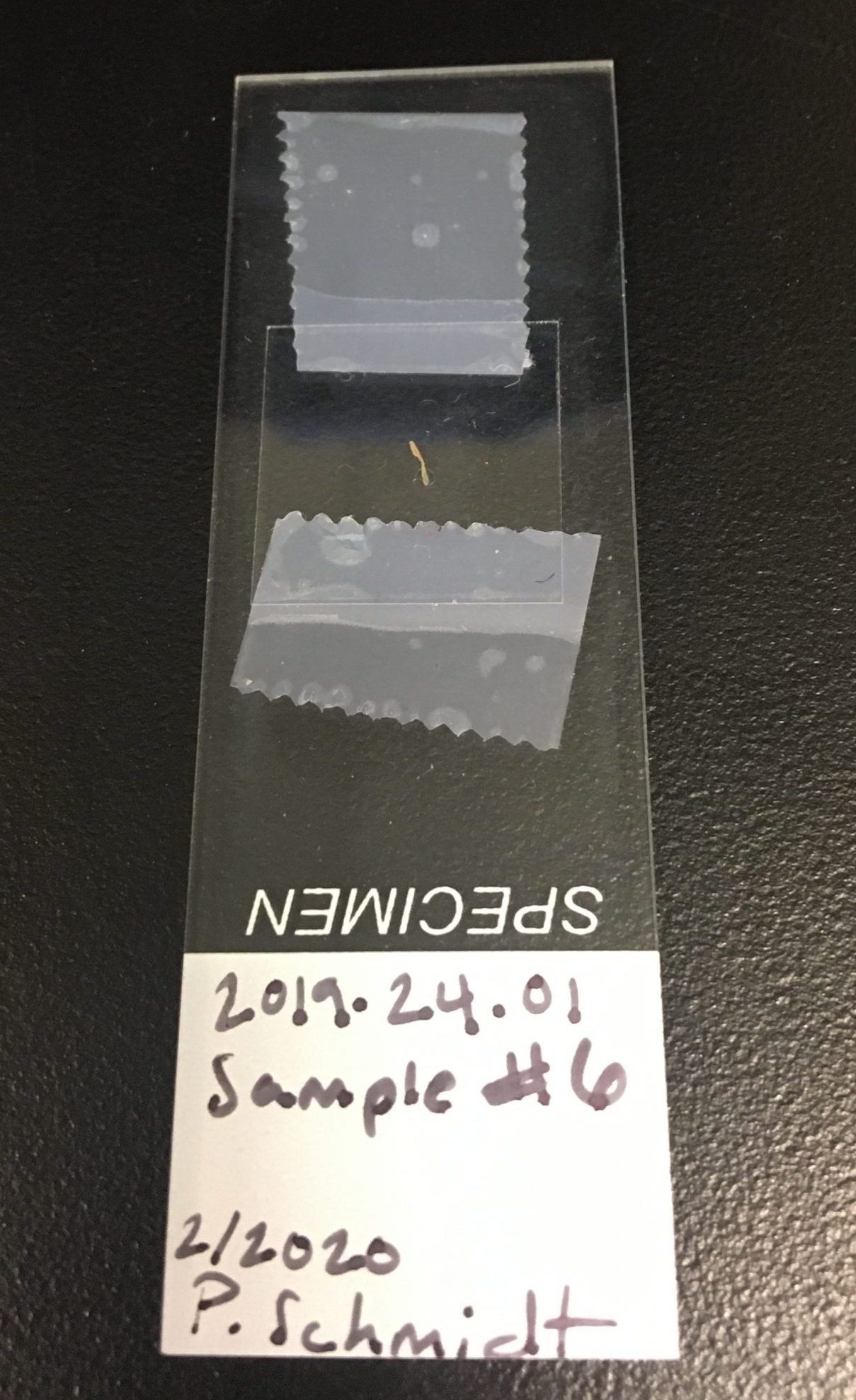

I began the analysis by taking very small samples of the sewing fibers and fur for microscopic analysis. Whenever possible, conservators try to use methods of non-destructive analysis; however, sampling is sometimes deemed appropriate for the information gained, and the sample size necessary for microscopy is barely visible to the naked eye. Furthermore, the samples taken for microscopy are not destroyed by this analytical process, and can be saved for future reference or other forms of analysis. I obtained samples of five different threads or fibers used for the stitching, in addition to a short length of fur.

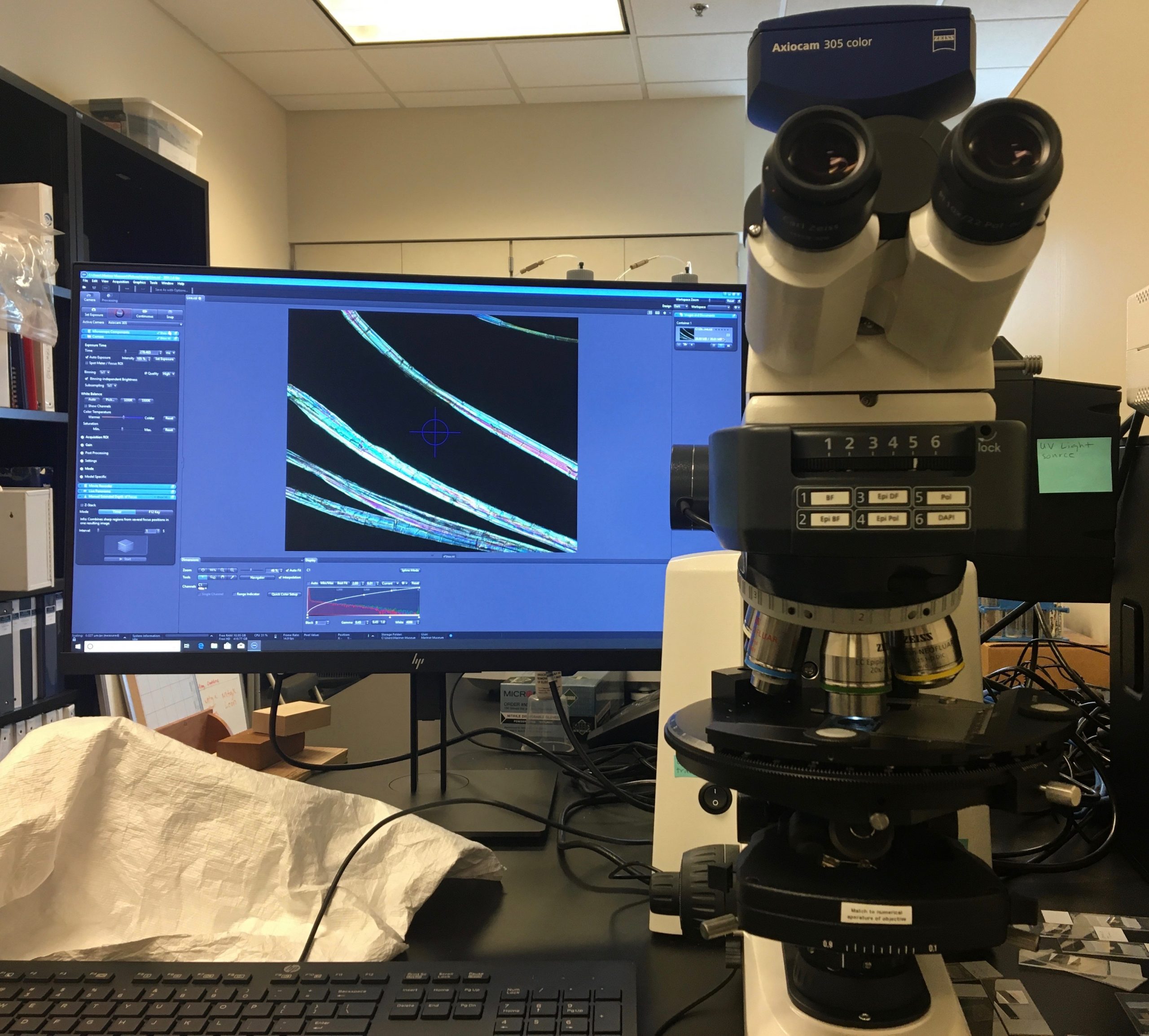

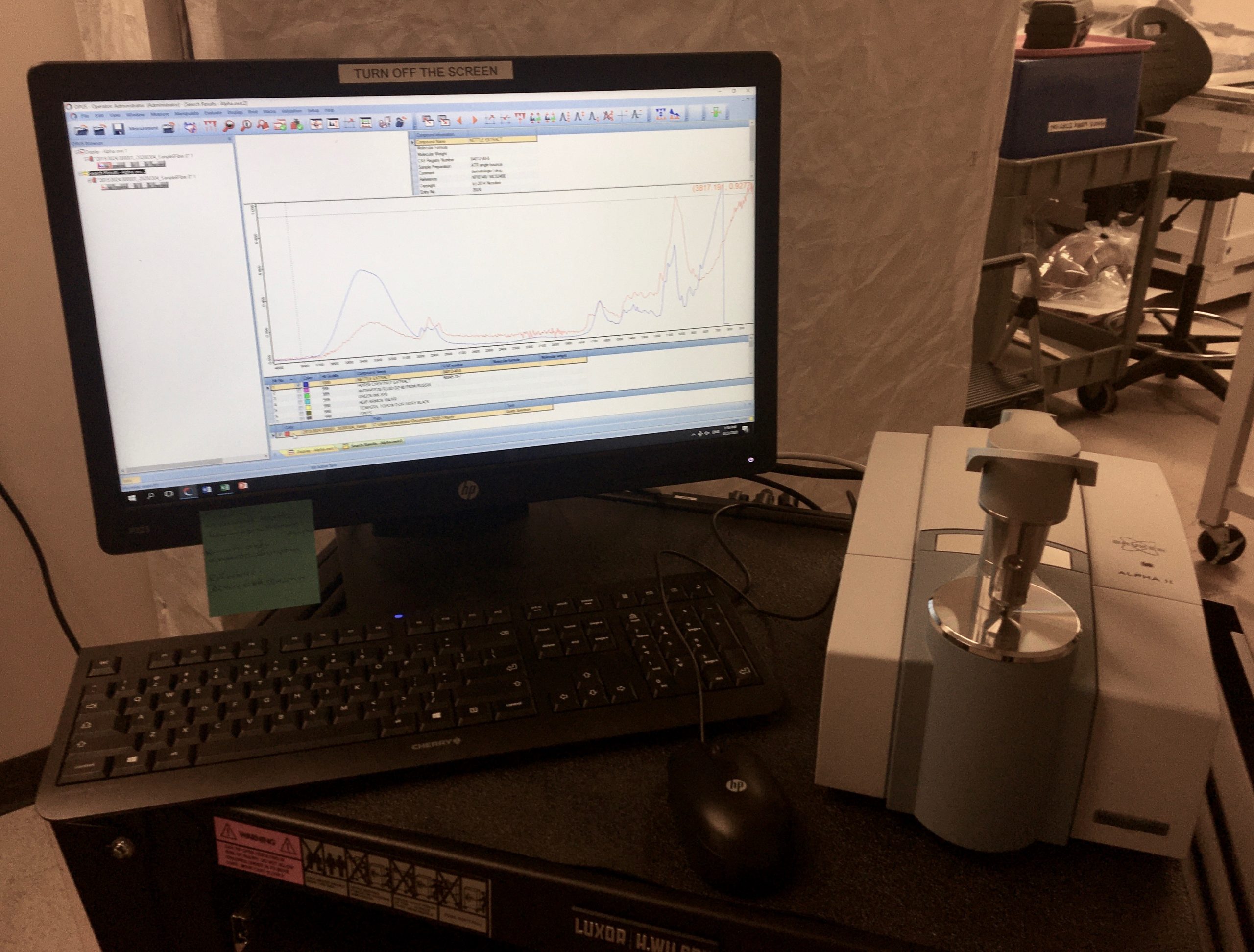

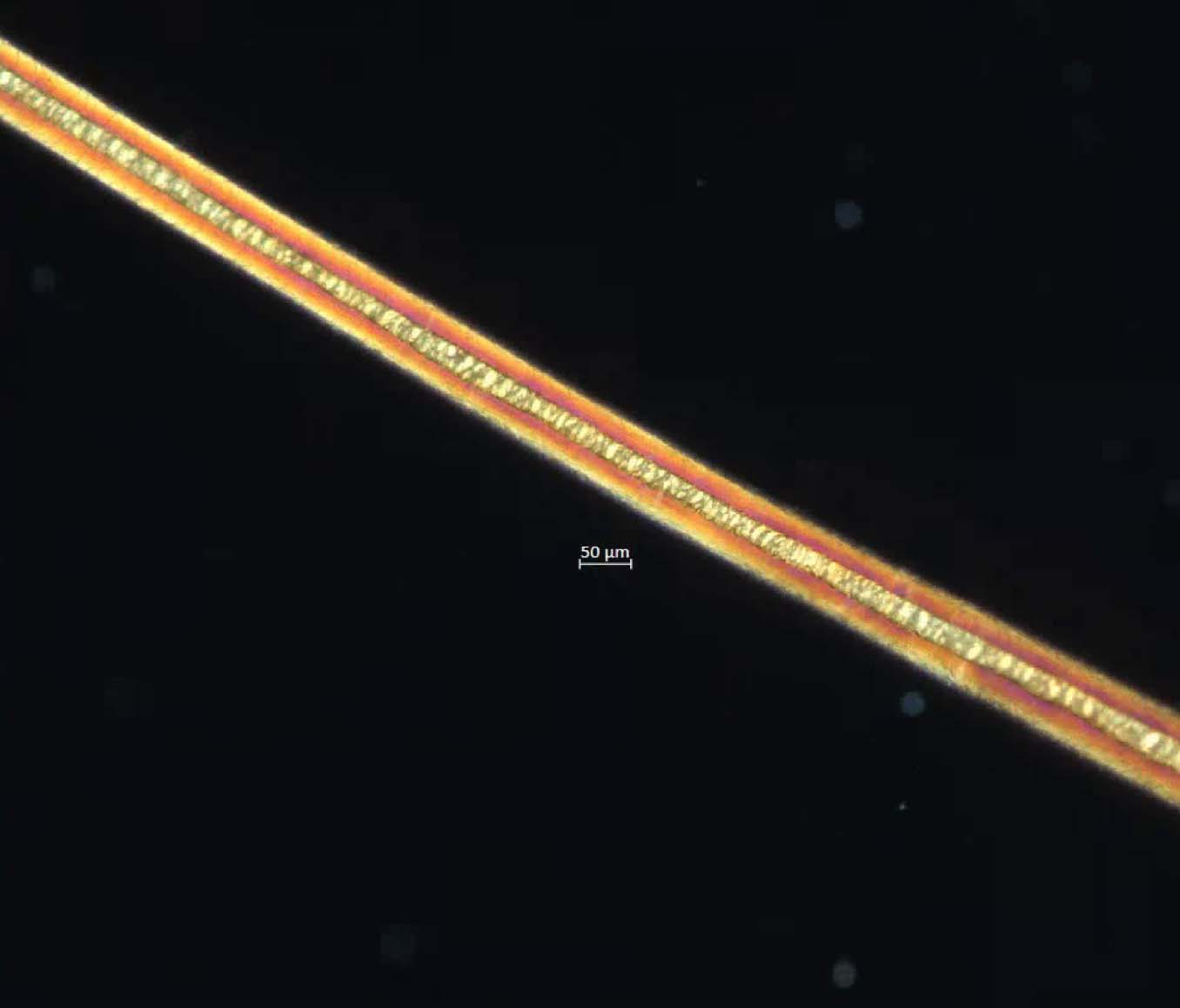

Microscopy revealed that most of the colorful dyed threads used for the stitching were cotton and/or linen (flax). Along with these colorful threads, most of the seams of the parka were also stitched with what was identified as a bast fiber under the microscope, and most closely matched with nettle fibers when analyzed with infrared spectroscopy.

Nettle fibers have been processed and used for cordage and thread for centuries by indigenous communities across the world, and is likely the fiber we are seeing here. While sinew was commonly used for sewing these types of garments, plant based fibers were often used to supplement the stitching, since they swell when wet and can aid in creating water tight seams. No evidence of sinew has been found on this particular parka, but anecdotal information from conversations with colleagues at other institutions suggests that much of the colorful stitching material may be embroidery thread, which in conjunction with the grass and stitching technique would still create water tight seams.

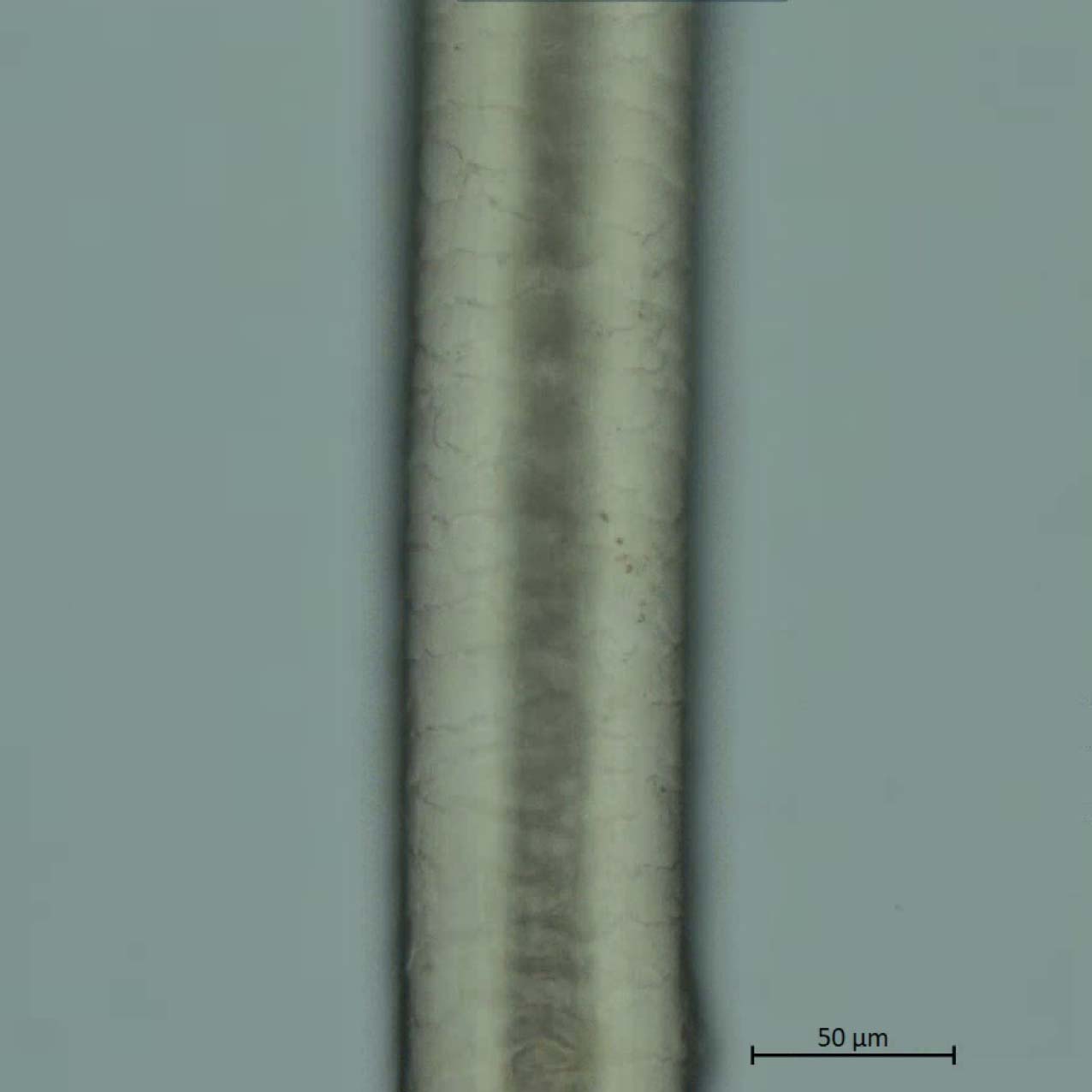

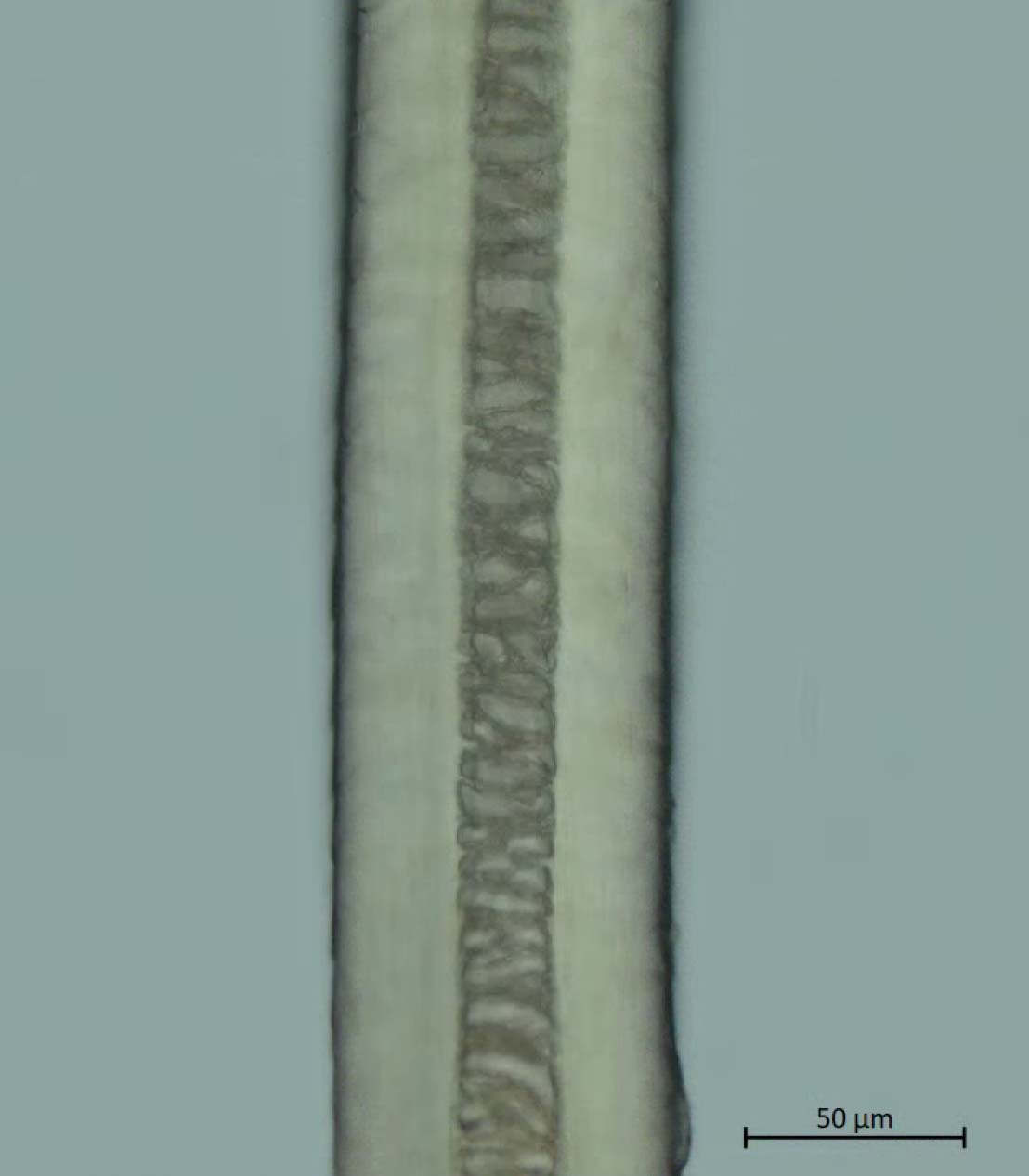

I next looked at the fur under the microscope, and was pleasantly surprised by what I found.

Based on the comparison of the features of the fur I was seeing with references provided by the Alaska Fur ID Project, I was fairly certain the fur I was looking at was polar bear! This assessment is based on features of the fur’s medulla, scales, cortex, and how light interacts with the fibers when viewed under different settings on the microscope. Although I felt pretty good about the characterization of the fur, I wanted some extra analytical input to confirm my identification. Fortunately, there is an analytical technique called Peptide Mass Fingerprinting (PMF), that can be useful for the identification of mammals based on the amino acid sequence of certain proteins (i.e. collagen). While this technique cannot be applied to the fur itself (which is mostly keratin), the skin to which it is attached is the perfect test subject.

I sent a sample of the skin to Conservation Scientist Daniel Kirby, who completed this testing for the Museum. And lo and behold, the skin’s marker ion’s matched with bear! The markers for bear cannot distinguish between species, but this information in conjunction with the macro and microscopic features of the fur provided me with enough information to feel confident about the identification.

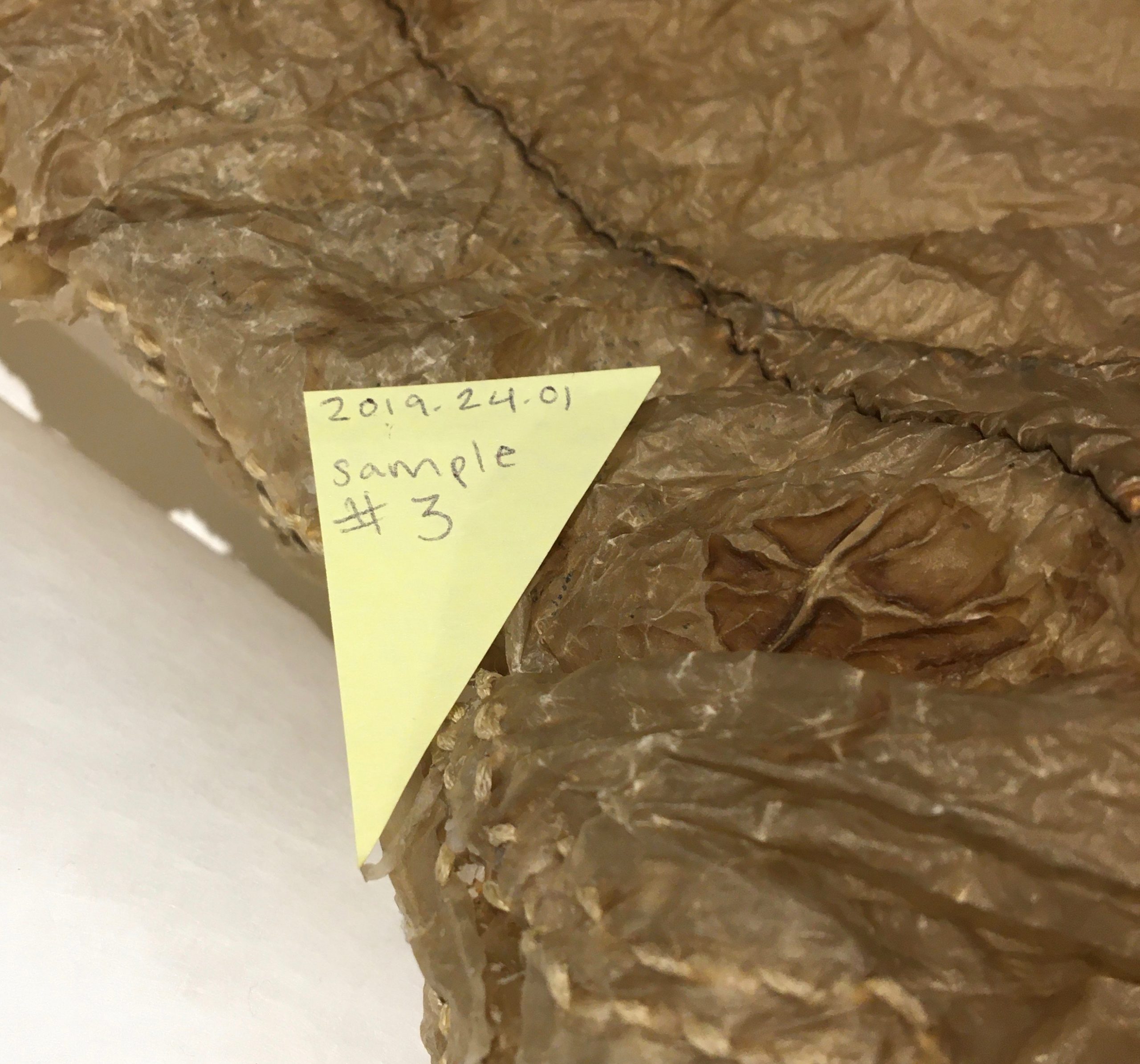

In addition to the skin, I also sent several small samples of the gut to Dr. Kirby for analysis. These samples were even smaller than the fibers I used for microscopy (<1mm), and were sampled from damaged exterior edges of the gut. Whenever this type of destructive analysis is performed, conservators take the utmost care when selecting sample sites, so that new areas of damage are not incurred.

As Jeanne mentioned in her post, we had received advice from Conservator Ellen Carrlee of the Alaska State Museum regarding the likelihood of the source of the gut. Carrlee, an expert on the characteristics of gut and its uses, posited that the gut was likely from bearded seal, given the location of its manufacture and practicality of the available materials. With the aid of Dr. Kirby and PMF, we were able to once and for all confirm a species identification… (drumroll please)…

… all sampled sections of the gut matched with bearded seal! Unlike bear, the peptide mass fingerprint of seals can be species specific, so our months long investigation was finally at a conclusive end.

The objects in our collection are so much more than static things we look at from behind glass. Their significance lies not in just how old they are (though some are a testament to the lasting nature of man made creations), or how beautiful they appear (though many are remarkable achievements of human artistry). The value of an object lies deeper than just the surfaces we see; artifacts also serve as primary documents that inform our understanding of the people that created and used them. Equipped with the information about the materials used to create this parka, we will be able to move forward with inquiries to native communities, institutions, and other experts in order to learn more about this parka’s significance and history. By sharing our finds with others, we hope to contribute to the conversation, as well.

This remarkable addition to the collection will certainly be the focus of research to come, and we will keep you abreast of our findings!