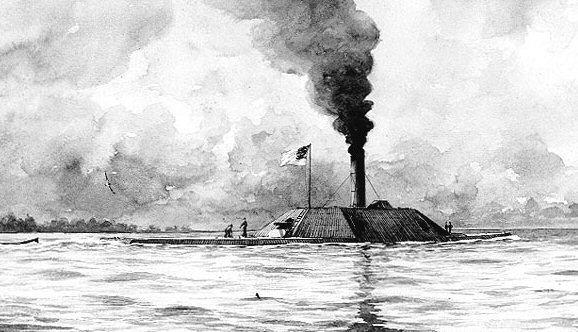

The ironclad CSS Albemarle’s stunning victory at Plymouth gave the Confederacy tremendous hope to expand their control of eastern North Carolina. Major General Robert Hoke was given permission to march against New Bern. However, the Confederate plans became disrupted when the Kinston-based ironclad, CSS Neuse, ran hard aground in its attempt to steam down the Neuse River to attack New Bern.

General P.G.T. Beauregard, head of the Confederate district of North Carolina, believed that Albemarle could be used to support the New Bern assault. “With its assistance,” he wrote, “I consider capture of New Bern easy.”

Utilizing an ironclad seemed the only way the Confederates could achieve victory. So, Commander James Cooke agreed to launch an attack. He knew that his ironclad, with a range of 150 miles, had to cross the Albemarle, Croatan, and Pamlico sounds to support the assault. Cooke also realized that the entire Confederacy was watching, their dreams of victory pinned on Albemarle. He had no choice but to carry out the effort to reach New Bern.

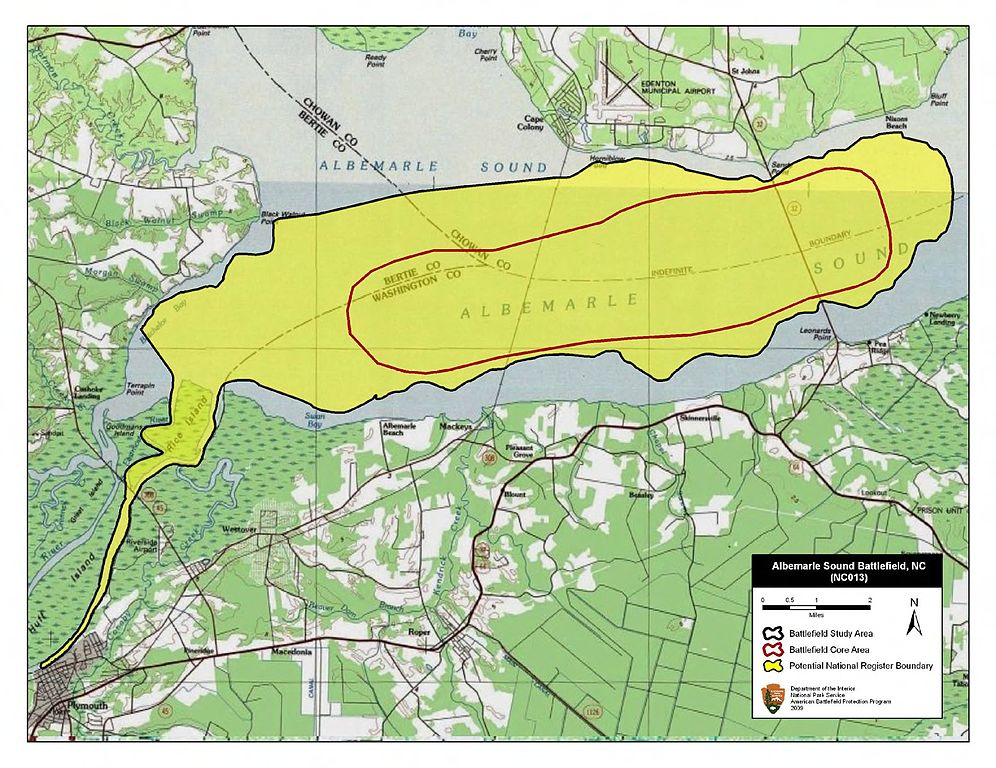

Albemarle Sound Battlefield, North Carolina. American Battlefield Protection Program. Courtesy National Park Service.

The Federals’ Response

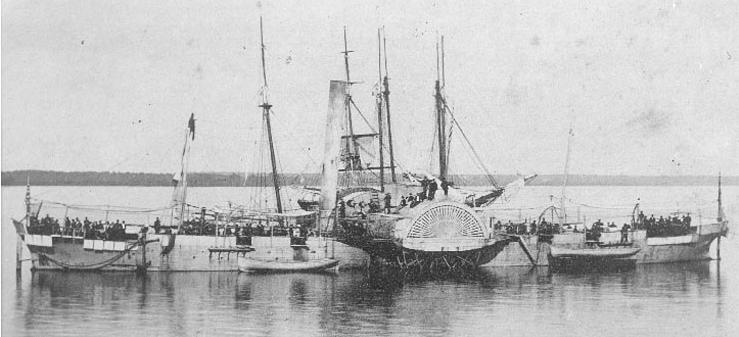

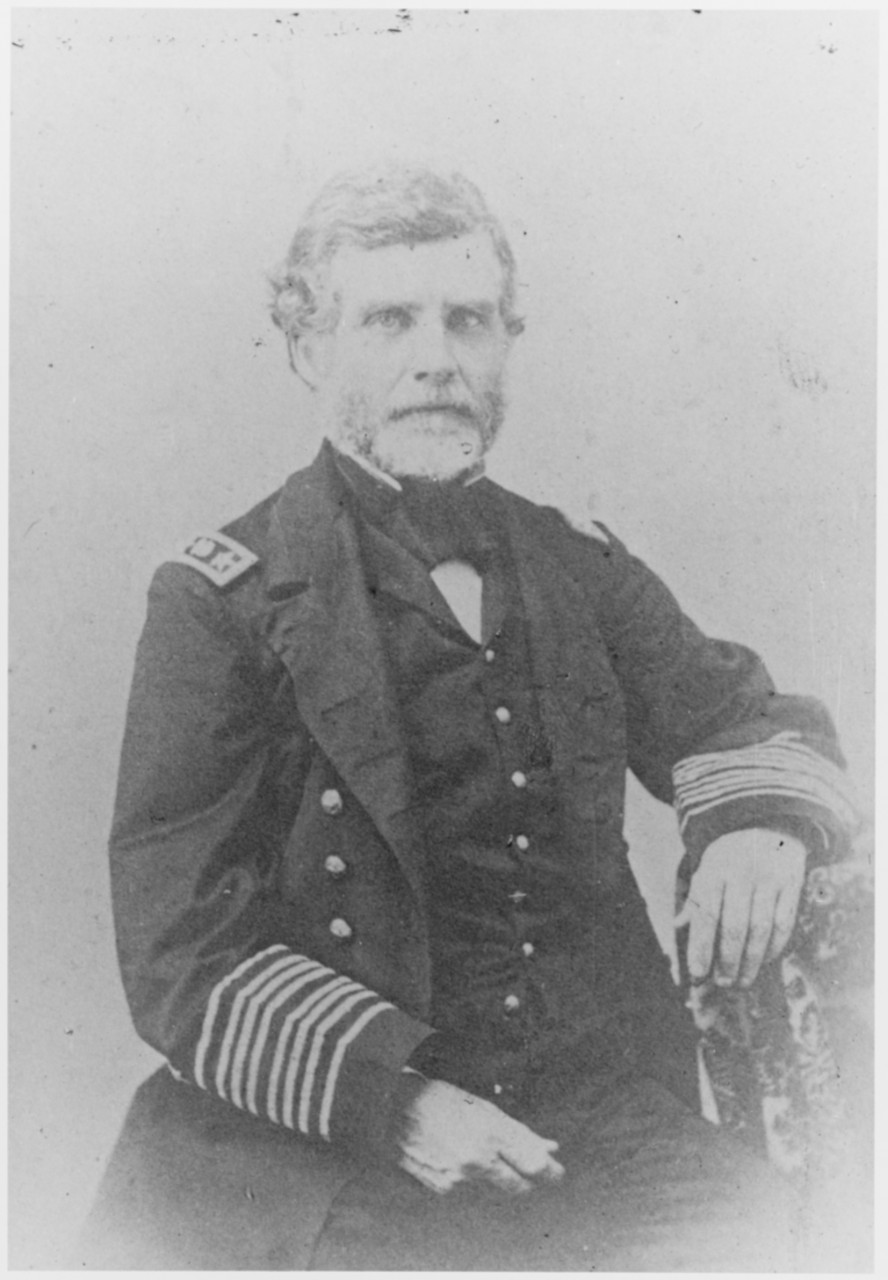

Admiral Samuel P. Lee, commander of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, had assembled a powerful flotilla of wooden gunboats to block any movement of Albemarle down the sounds. Commander Melanchton Smith was the squadron’s commander with his flag in USS Mattabesset. Smith decided to send his double-enders in a line ahead as they passed the ram.

Vessels like USS Wyalusing, USS Miami, and USS Sassacus each had a heavy battery of two 100-pounder Parrott rifles and four IX-inch Dahlgren, along with other smaller cannons. These sidewheelers awaited the ironclad that they knew would surely come.

The Battle Begins

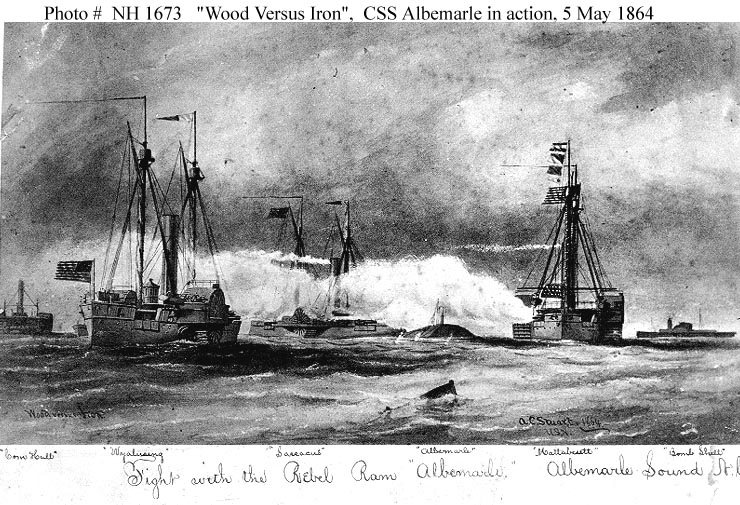

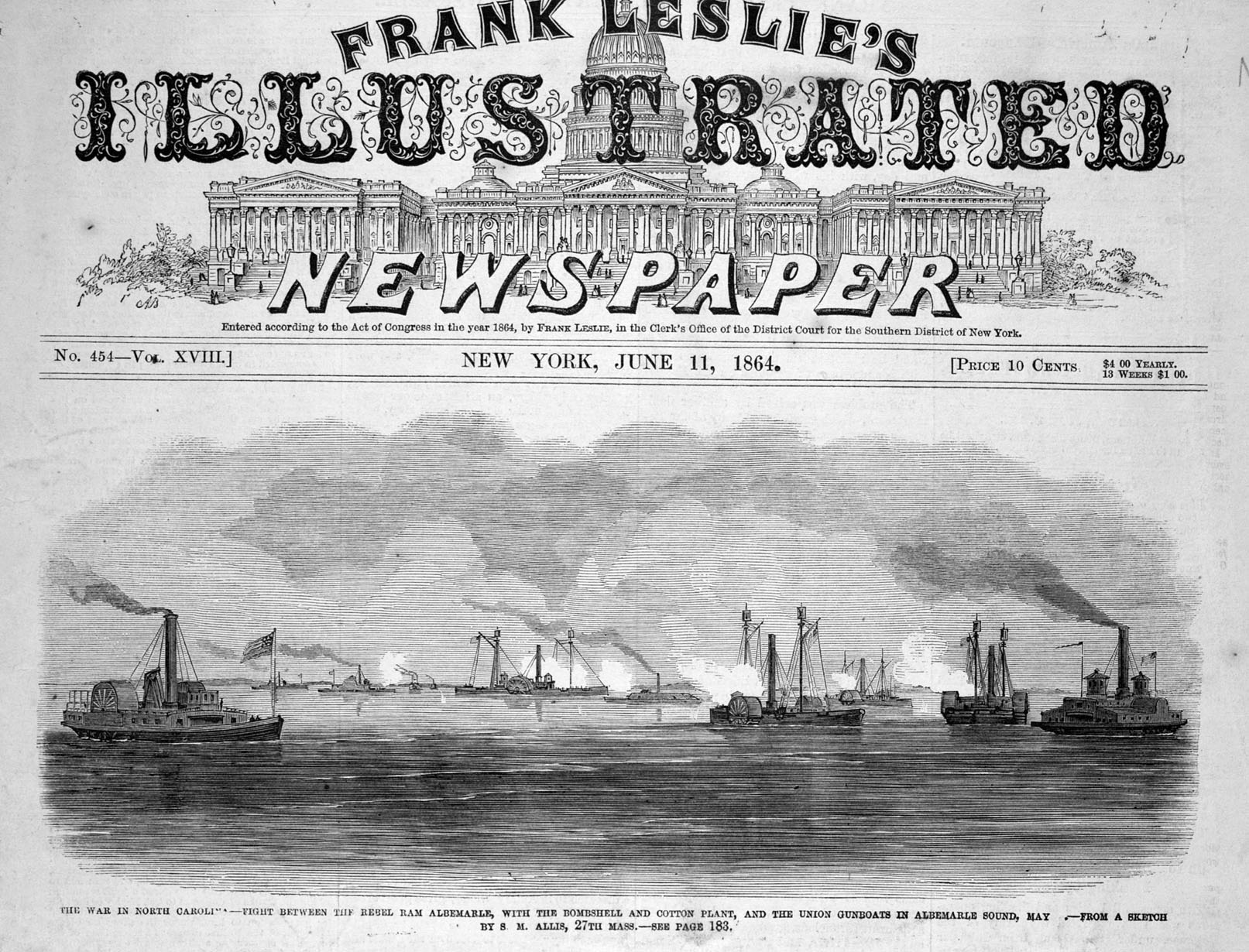

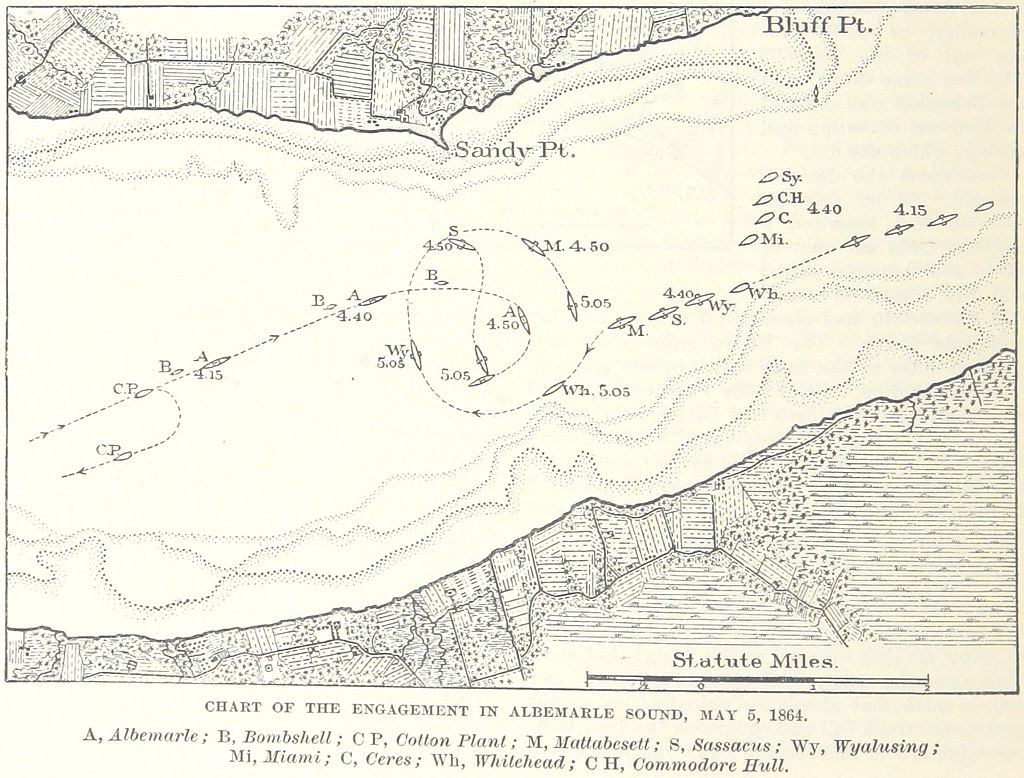

On May 5,1864, CSS Albemarle stood out from the Roanoke River and steamed south into its namesake sound. The ironclad was accompanied by two wooden gunboats, CSS Cotton Plant and CSS Bombshell. Cooke sighted the Union squadron in the Albemarle Sound off Sandy Point, and steamed toward them.

Cooke tried to ram the lead Union ship; however, he fired his forward Brooke gun into the advancing Union vessel. That first shot destroyed Mattabesett’s launch and wounded several men. Albemarle then attempted to ram Mattabesett; yet, the Federal sidewheeler had greater speed and was able to round the ironclad’s bow, escaping the deadly ram.

Try, Try Again

Commander Smith ordered his three heavy double-enders to steam past Albemarle and Bombshell. Mattabesett was the first to engage the ram. The broadside punished Albemarle. “One shot,” according to crew member John Patrick, “knocked in us, but not all the way through, splinters of wood flew about.” It was the third or fourth shot that struck Albemarle’s stern 6.4- inch Brooke rifle, blowing off 23 inches of the gun’s muzzle.

The Confederates continued firing the Brooke gun when Mattabesett passed. The sidewheeler was severely struck by shells from the ram. One shell dismounted one of Mattabesett’s guns with “every man at the gun either killed or wounded.” Then the flagship passed the ironclad and engaged CSS Bombshell.

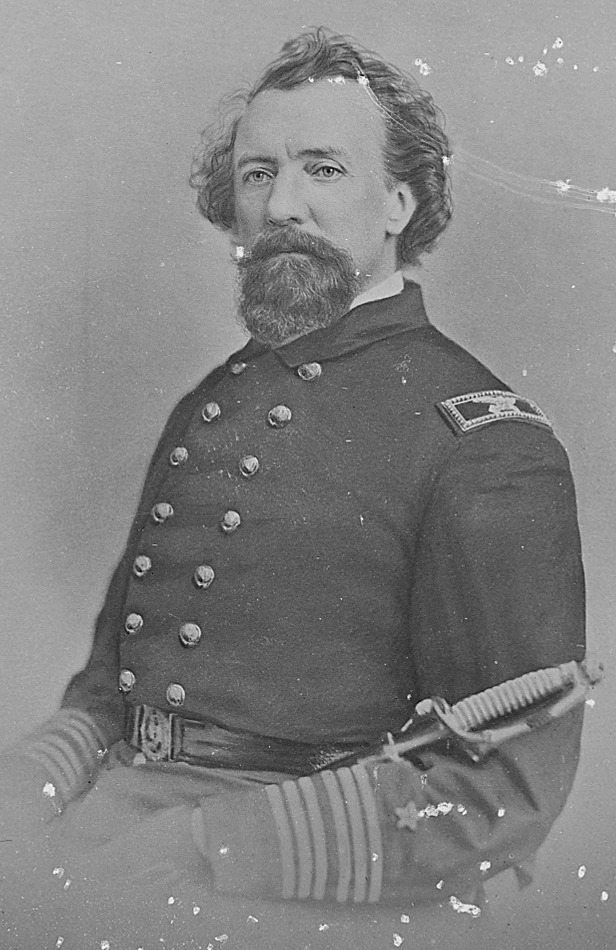

Sassacus and Wyalusing passed Albemarle, sending broadsides against the sloped sides of the Confederate ram to no effect. Sassacus then encountered Bombshell and forced the gunboat to haul down its colors. USS Cotton Plant retreated to the Roanoke River. Sassacus’s brief engagement with Bombshell placed the gunboat more than 300 yards away from the ironclad. Sassacus’s commander, Lieutenant Commander Francis A. Roe, decided to ram Albemarle. Saccacus had been specially fitted with a brass ram at its bow, so Roe thought his ship could do some damage to the Confederate ironclad.

Ramming Speed

Sassacus rammed Albemarle just abaft its starboard beam, right where the ironclad’s casemate joined the vessel’s stern. The Union gunboat kept up full power which drove Albemarle’s starboard down. Water then rushed into the gun port. “Stand to your guns,” Commander Cooke shouted, “if we must sink let us go down like brave men.” Albemarle sent a shell through Sassacus’s hull, which had already been damaged by the ram’s iron-plated knuckle, cutting into, and severely damaging the gunboat’s bow as the ships passed each other.

Cooke ordered Albemarle to turn “hard aport.” The ironclad’s stern swung wide to port and the vessel broke away from the Union gunboat. The bow Brooke rifle was pivoted to the starboard forward port and fired at Sassacus at point blank range. The muzzle blast scorched the Union vessel’s paint. Albemarle’s second shot tumbled through Sassacus, piercing the gunboat’s boilers. Steam and boiling water blew through Sassacus. The vessel broke off action and drifted out of range.

How Many Ways Does It Take to Destroy an Ironclad?

The repaired USS Miami, fitted with a spar torpedo and a seine net, attempted to torpedo Albemarle, but could not get into position. The seine net failed to foul the ironclad’s screws. Miami was struck by a shot from the Confederate ram. The gun boat’s rudder was damaged, a shot destroyed the captain’s cabin, another shell smashed the pilot house, and the sidewheeler had its funnel peppered with shot. Miami fell back from its second close encounter with Albemarle. Wyalusing and USS Commodore Hull engaged the ram. However, neither ship could stop Albemarle.

Return to the Roanoke

As nightfall came, Albemarle, running low on fuel, broke off action and returned to the Roanoke River. The Confederate ironclad was seriously injured during this three-hour engagement. The ironclad only had one man killed; nevertheless, the ram suffered other damage. Its stern Brooke gun’s muzzle was shot off, several iron plates had been knocked away from the wood backing, the steering mechanism was partially broken, and its smokestack had been so damaged that the men in the engine room had to throw bacon, lard, and butter onto the boiler fires to keep the engines running on the ram’s return to Plymouth.

‘A Force in Being’

The engagement had been a tactical draw. However, Albemarle was unable to participate in the attack on New Bern, leaving the town under Union control. Lieutenant Commander Francis Roe of USS Sassacus called Albemarle “more formidable than Merrimack or Atlanta, for our solid 100-pounder rifle shot flew into splinters upon her ironplates.”

While Albemarle existed, the ram was a “force in being,” Roe continued. This enabled the Confederates to retain part of eastern North Carolina until a solution was found that would result in this defiant ironclad’s destruction.

Excerpted from A History of Ironclads: The Power of Iron Over Wood, John V. Quarstein. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2006. Available in the Museum’s Web Shop: https://shop.marinersmuseum.org/a-history-of-ironclads.html