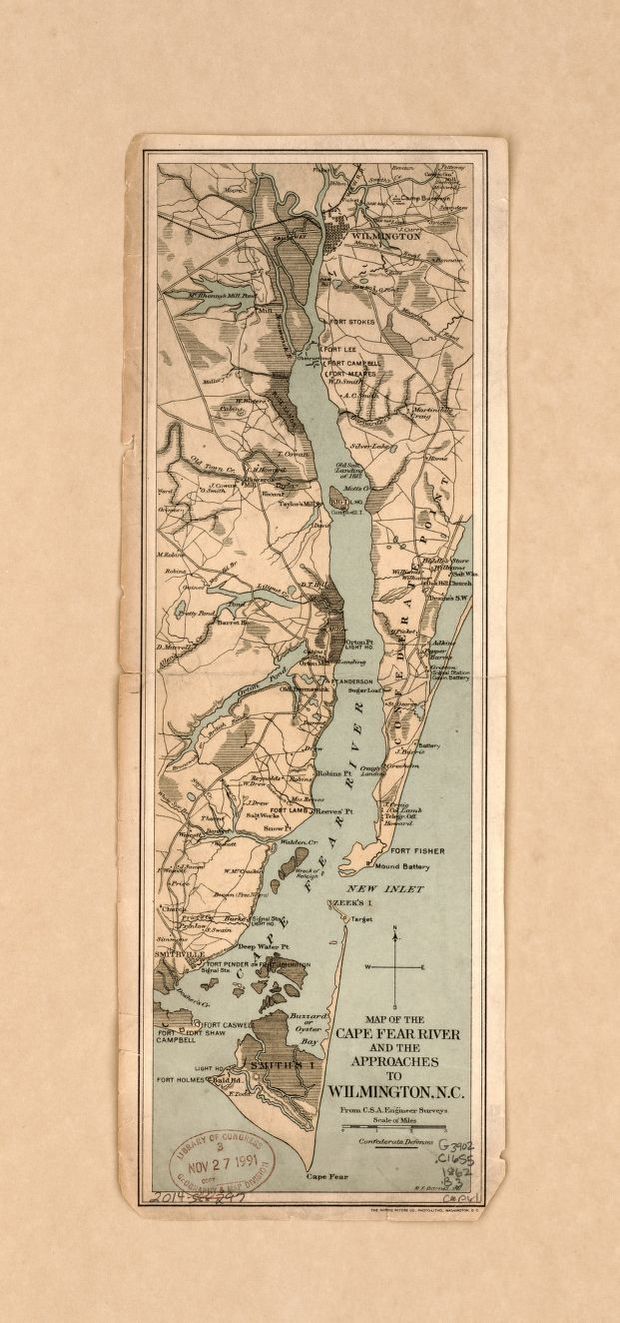

As the Union warships sailed away from Cape Fear on December 27, 1864, Colonel William Lamb, Fort Fisher’s commander, wired Richmond, “This morning … the foiled and frightened enemy left our shore.”Richmond rejoiced as Wilmington, North Carolina, remained the Confederacy’s only outlet to the world.

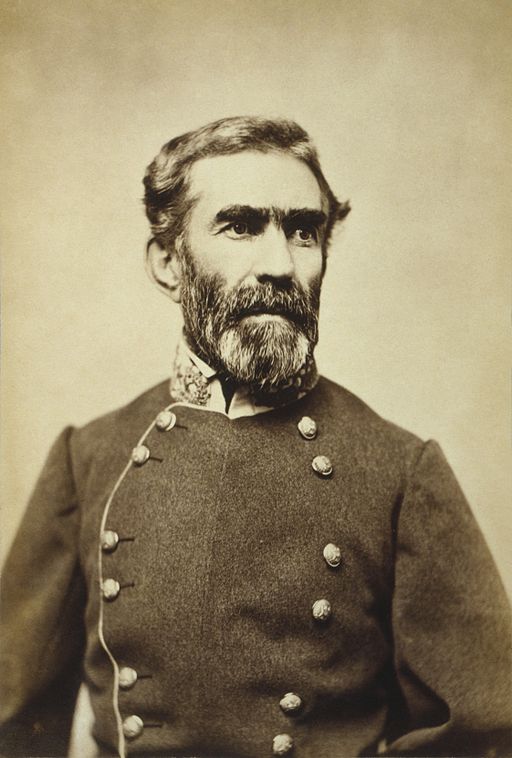

Bragg Takes Command

Lamb quickly organized repairs to the minor damage the fort suffered during the bombardment. Both he and Major General W.H.C. Whiting knew the Federals would soon return. General Braxton Bragg had recently assumed command of the District of North Carolina. He rebuffed every request for reinforcements to the fort’s garrison. Bragg did not believe that the Federals would return and thought it more prudent to defend Wilmington.

Bragg failed to recognize that Fort Fisher was the main fort guarding the Cape Fear River and without it, Wilmington would be worthless. Major General Robert Hoke, positioned further up the peninsula from Fort Fisher, was ordered by Bragg to stay on the defensive.

Federal Task Force Revitalized

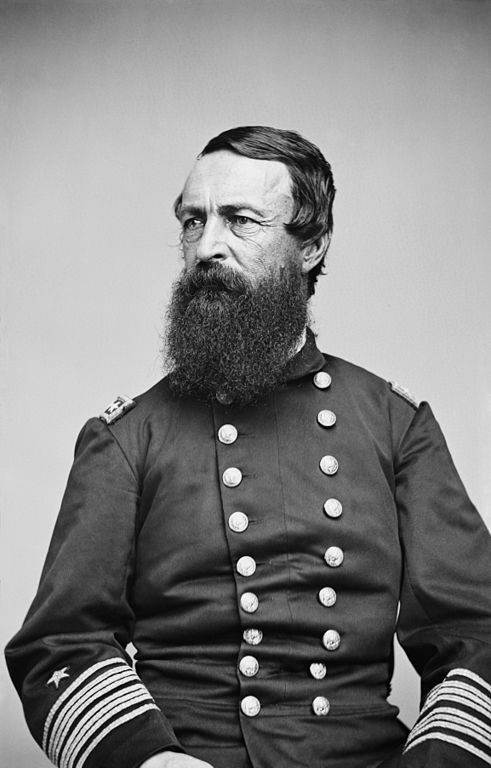

General U.S. Grant knew that the capture of Wilmington would force the Confederates to abandon Richmond and Petersburg. Grant replaced the inept B. F. Butler with a more dynamic officer: Major General Alfred Howe Terry. A Yale-educated lawyer, Terry was clerk of the Superior Court of New Haven County, Connecticut. When the war erupted, he raised a regiment and fought with distinction in South Carolina and Virginia. Terry was given command of a 9,000-man expeditionary force to capture Fort Fisher. The task force commander knew that he needed to have close coordination with the US Navy, so he forged a great working relationship with Rear Admiral D. D. Porter.

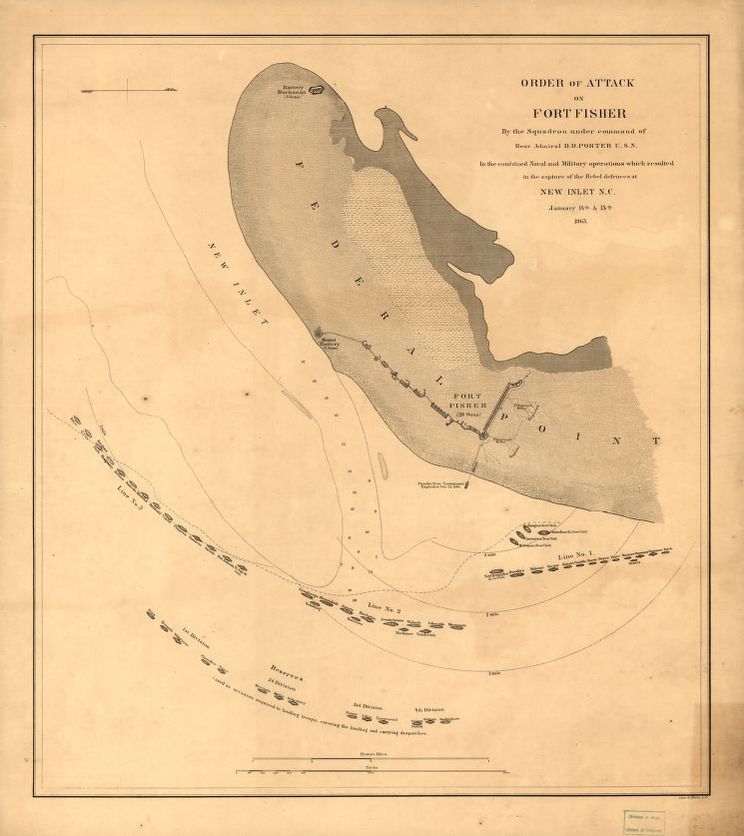

Porter, as commander of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, was able to support land operations with his ship’s heavy artillery. Porter knew the bombardment had to be better managed than the previous shelling of Fort Fisher. The two officers planned a joint land attack. Terry would send one of his two divisions along with three US Colored Troops brigades to block Hoke from any offensive action. Terry’s other division, commanded by Brigadier General Adelbert Ames, would attack the fort’s land face. The navy would add punch to the attack as Porter had assembled a force of 2,000 naval personnel and Marines to make a land assault to capture the Northwest Bastion.

The Bombardment

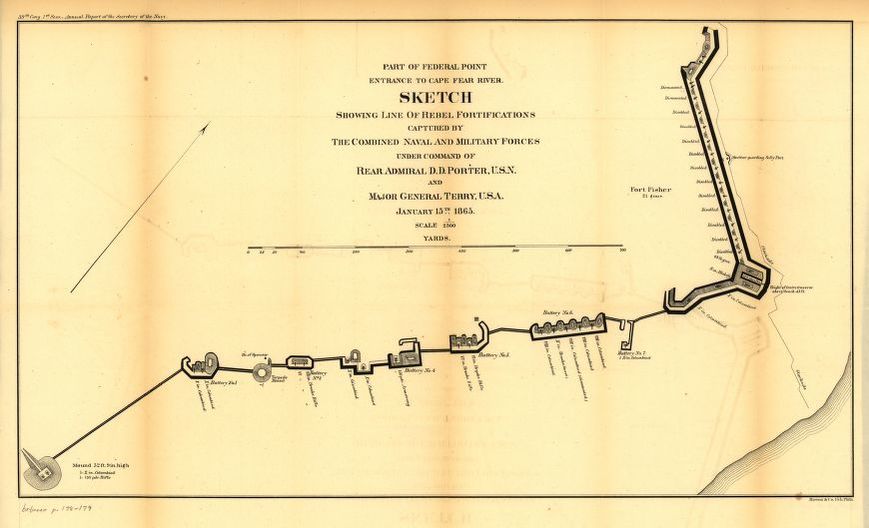

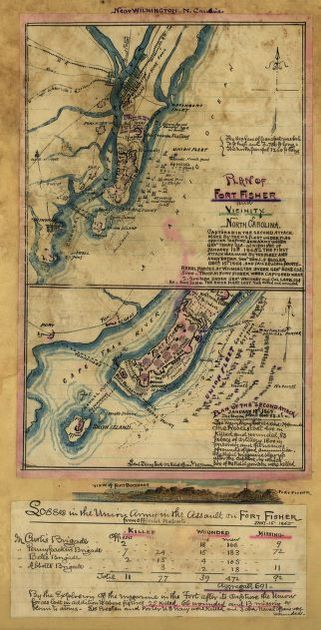

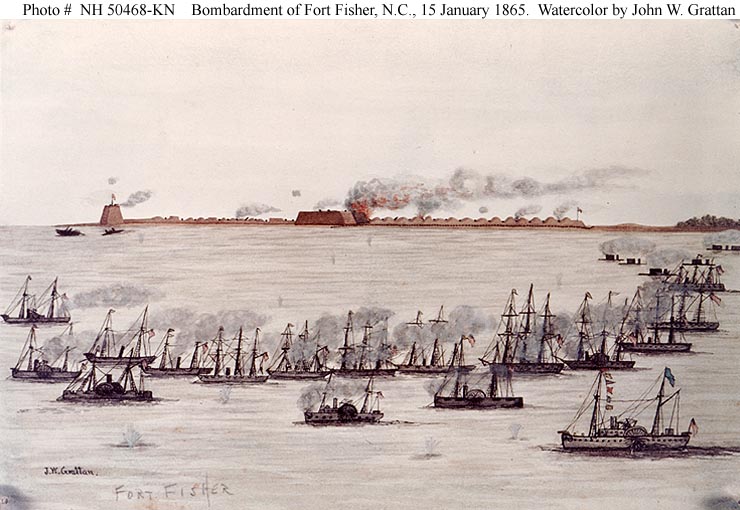

Admiral Porter deployed his vessels in three crescent-like lines off Fort Fisher. The monitors Canonicus, Monadnock, Mahopac, and Saugus came within one-half mile of the fort, and their gunnery was focused on the Northeast Bastion. The next line of 14 ships situated about one mile off the shoreline, included USS Brooklyn and New Ironsides. These ships aimed their guns on the land face.

The third line of heavy ships featured USS Minnesota, Wabash, Powhatan, Maratanza, and Rhode Island. These frigates and gunboats sent shot and shell directly into the fort’s sea face. Lighter ships in reserve were used to bring ammunition and coal to the forward warships. Porter had 57 ships mounted with more than 600 cannons to pound Fort Fisher virtually into submission. Each ship had a specific target and knew that the major gun positions needed to be demolished by direct and enfiladed fire.

The Federal fleet arrived off Confederate Point on January 12, 1865. Just after dawn the next day, Porter began his squadron’s well-orchestrated bombardment. The same day, Gen. Terry surveyed the fort and on January 14, decided that he would launch his attack the next day.

‘You and Your Garrison Are to Be Sacrificed’

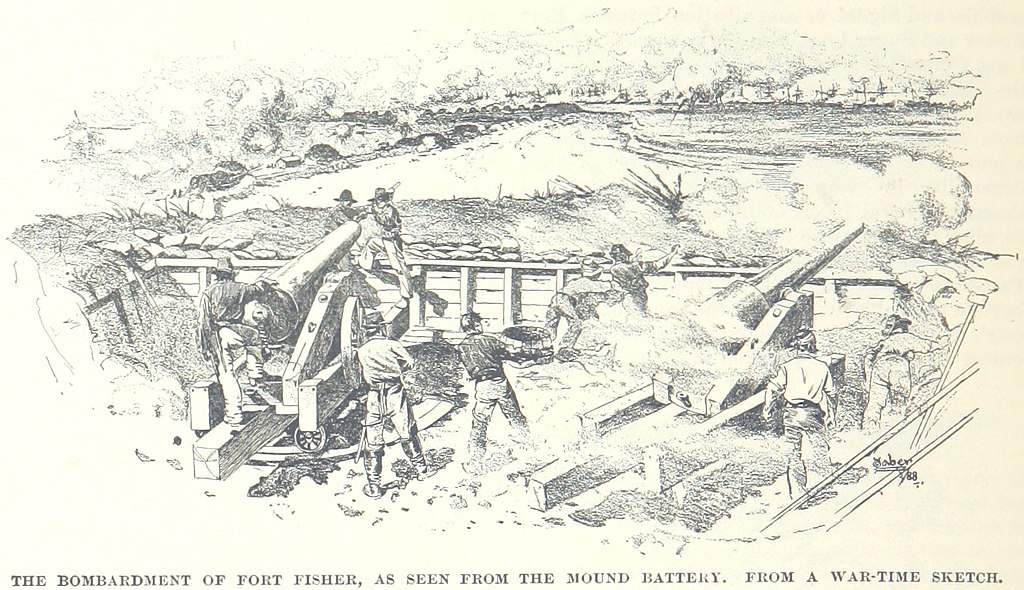

The bombardment created havoc and destruction within the fort. Colonel Lamb remembered that “the navy continued its ceaseless torment; it was impossible to repair damages at night on the land face. The New Ironsides and monitors bowled their 11 and 15 inch shells along the parapet, scattering shrapnel in the darkness.” Fortunately, many Confederates stayed in the bomb proofs; however, Lamb counted more than 200 casualties. He desperately worked to defend against the infantry onslaught he knew would eventually come.

Whiting pleaded with Bragg for reinforcements. Bragg did send some; but, surely not enough. By the time of the ground attack, the garrison could only muster 1,900 men. Only four of the land face artillery were still usable. Likewise, the sea face had most of its guns dismounted or damaged.

General Whiting, disgusted with Bragg’s inaction, went to join Lamb in Fort Fisher. When they met atop a parapet, Whiting said, “Lamb, my boy, I have come to share your fate. You and your garrison are to be sacrificed.”

“Don’t say so, General,” Lamb replied, “we shall surely whip them again.”

Boarding the Fort

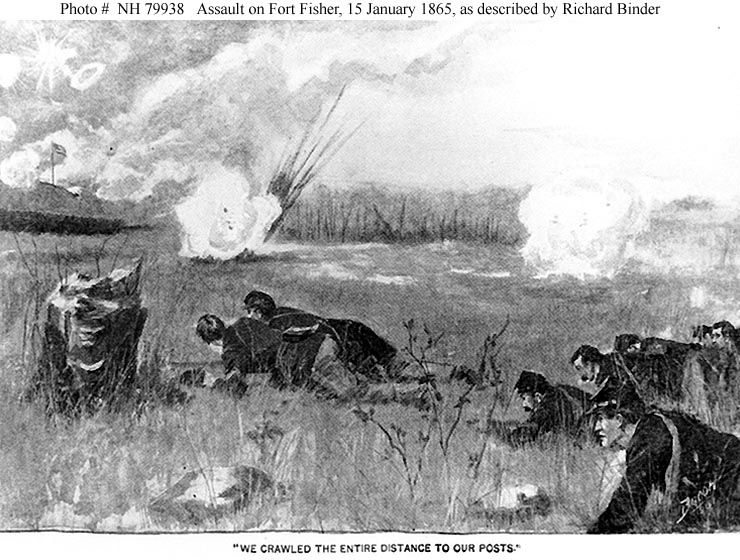

Terry had previously agreed to Porter’s plan to launch a naval assault on the Northeast Bastion’s Crescent Battery where the sea and land faces met. Porter, always seeking to gain greater glory for himself and the US Navy, believed that 1,600 bluejackets and 400 Marine volunteers could “board the fort on the run in a seaman-like way.”

The plan entailed the sailors be armed with revolvers and cutlasses. They were supposed to break down what was left of the palisade wall and then scale the fort to attain victory. The Marines were stationed to project covering fire as the bluejackets ‘boarded the fort.’

Lieutenant Commander Kidder Breese commanded the movement. The attack was supposed to have started at 2 p.m. when the naval bombardment ended. That time passed and the sailors as well as the Marines, became confused and crowded together. The naval fire stopped at 2:30 p.m., and Breese ordered his men to charge. The men gave a great cheer and attempted to climb the bastion. The Confederate soldiers were waiting for them. General Whiting personally led the Confederates as they poured canister, grapeshot, and musket balls into the mass of naval personnel.

Lieutenant Commander Thomas O. Selfridge Jr. remembered how the “men were packed like sheep in a pen.” The naval boarding party was repulsed as the men fell back to their boats. The naval attack resulted in almost 400 casualties.

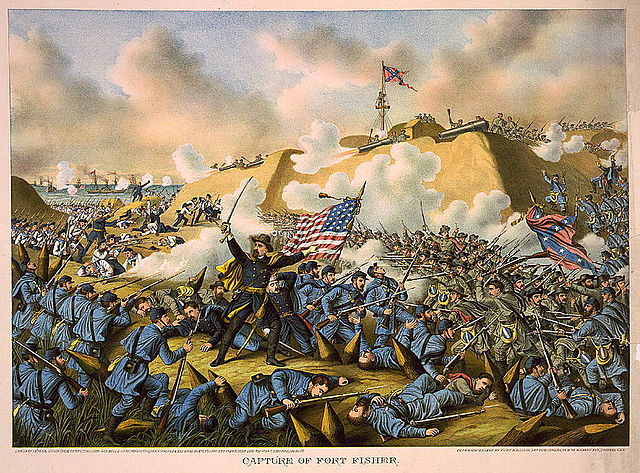

Gibraltar is Overwhelmed

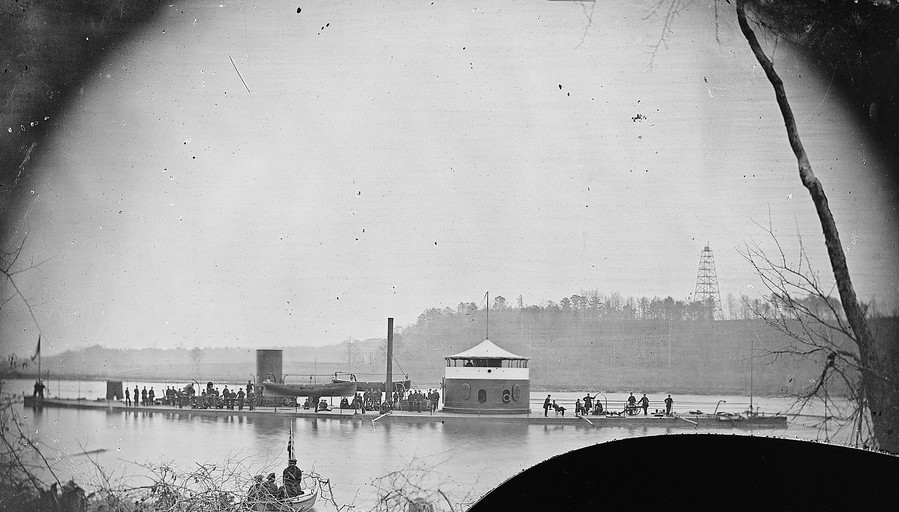

The Confederates were jubilant as they pushed the Federals back into the sea. Lamb, however, quickly glimpsed United States flags at the western end of the land face. General Ames’s division had rushed down the River Road which led to the fort’s entrance. As the Federals began to advance along the Cape Fear River, the Confederate gunboat, CSS Chickamauga, sent shells into the advancing troops; but Ames pushed his men forward. They were able to break through the gate. Then they had to fight hand-to-hand with the Confederate defenders.

General Whiting rushed to organize the defense of the western salient. En route, Whiting was shot down and critically wounded. As the Union soldiers battled through each traverse, Admiral Porter organized pin-point fire from New Ironsides to clear out the Confederate defenders ahead of the Federal advance. Fighting was extremely fierce and caused many casualties. Two of Ames’s brigade commanders, Col. Newton Curtis and Col. Galusha Pennybacker, were severely wounded; the other brigade’s commander, Louis Bell, was mortally wounded.

Colonel Lamb rallied his men and gathered everyone who could walk to mount a counter-attack. Lamb was critically wounded and turned the command over to Major James Reilly of the 10th North Carolina. Reilly had hoped to organize a final stand at Battery Buchanan. Once he arrived there, the defenders had spiked all the artillery and fled. Just at that moment, Brigadier General Andrew Colquitt arrived to take command of the fort. Bragg had become very tired of the constant calls for reinforcements and now, it was too late. Colquitt did a turnabout and left Battery Buchanan. Major Reilly had no choice but to surrender the fort with a white flag. Terry then met with Whiting to conduct the official surrender of Fort Fisher.

Final Act

Near dawn on January 16, 1865, two drunken sailors with torches entered Fort Fisher’s main magazine looking for souvenirs. The resulting explosion killed the sailors as well as injured 105 New York soldiers asleep atop the magazine. While it was such a sad finish to a tremendous and resounding victory, the battle that captured Fort Fisher hammered the last nail into the Confederacy’s coffin.

Excerpted from A History of Ironclads: The Power of Iron Over Wood, John V. Quarstein. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2006. Available in the Museum’s Web Shop: https://shop.marinersmuseum.org/a-history-of-ironclads.html and Confederate Goliath: The Battle of Fort Fisher, Rod Gragg. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1991.