Some of my most interesting research projects begin with something very minor, which leads me down a path that I never expected. This one began with a beautiful watercolor showing Camogli, Italy with a church and part of a castle behind it. That was a quick research project: get the history of the structures that are featured and the name of the body of water. Then I looked up the history of the artist, which is where it all unraveled into several days of research.

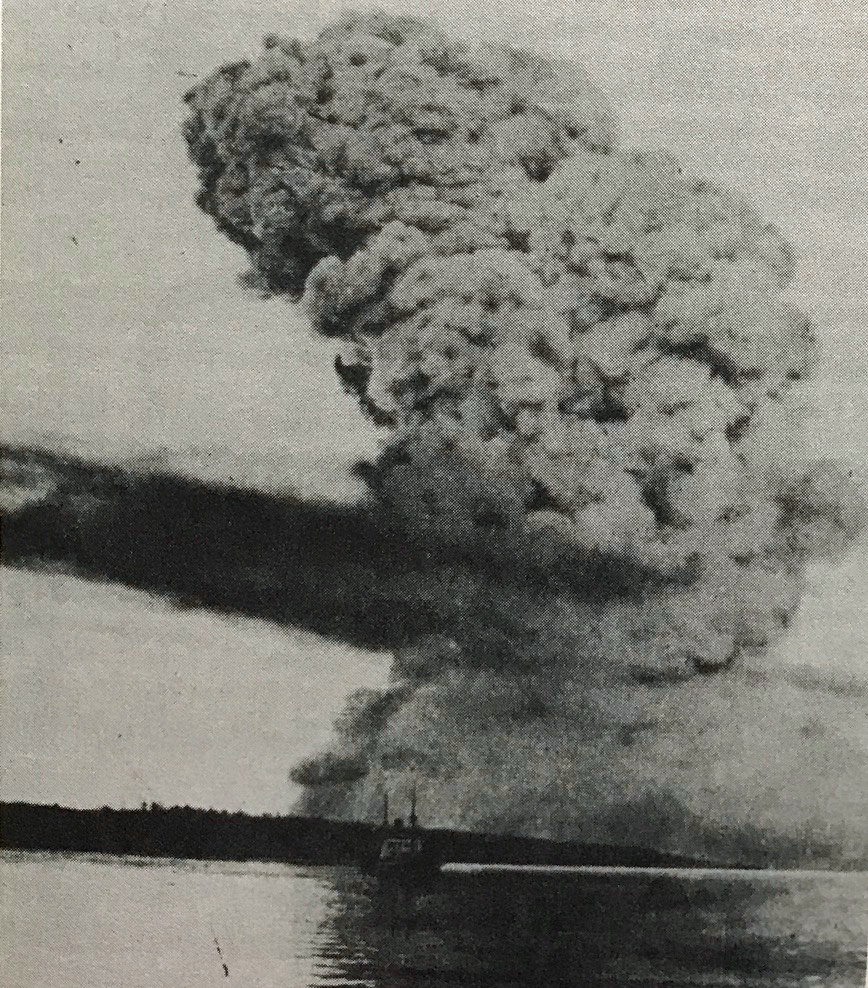

The artist is Admiral Bertram Mordaunt Chambers, a British naval official who was the principal port convoy officer of Halifax harbor during the December 6, 1917 explosion. His official reports state that he ate breakfast overlooking the harbor through his large glass windows, and then five minutes after he left the room the glass shattered into tiny shards that tore up the woodwork that had been behind his seat. He is one lucky guy!

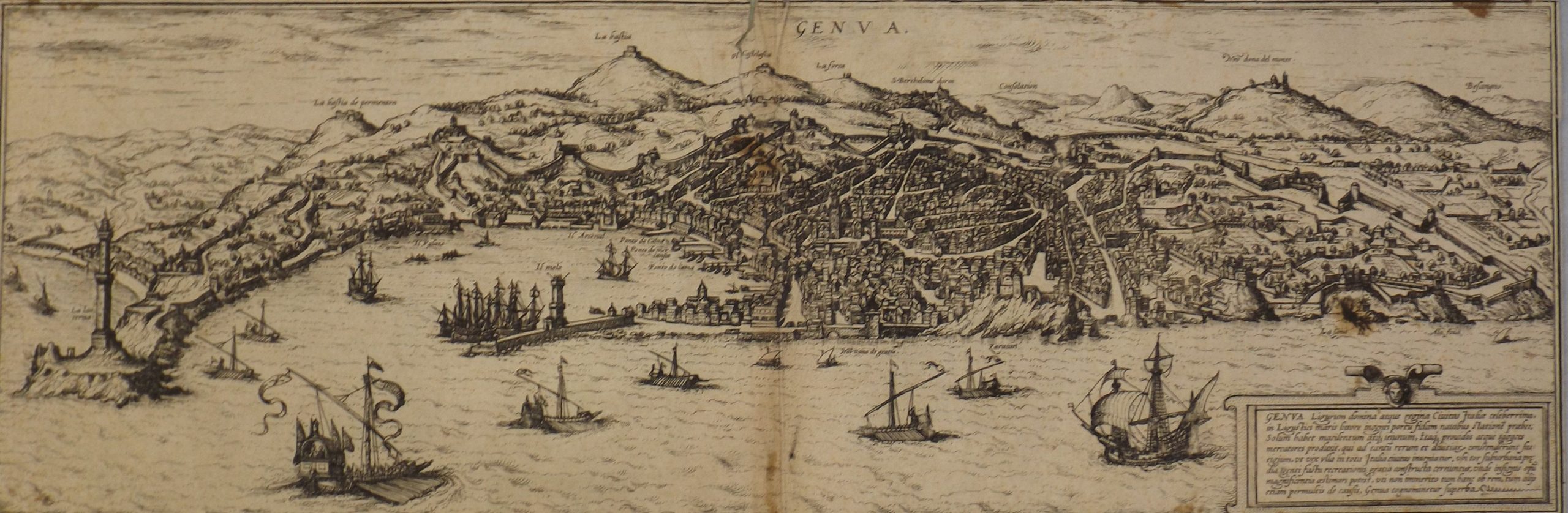

After his retirement from the British Navy, Admiral Chambers became an agent for The Mariners’ Museum and Park, purchasing many different objects for our collection, including the two large white figureheads in the lobby. In 1937 Admiral Chambers wound up in Italy on a buying trip, and his letters state that he was unable to find objects at an agreeable price, so he painted his own. How lucky are we to have had such talented agents?! We have six watercolor paintings from him, three of Camogli and three of Genoa.

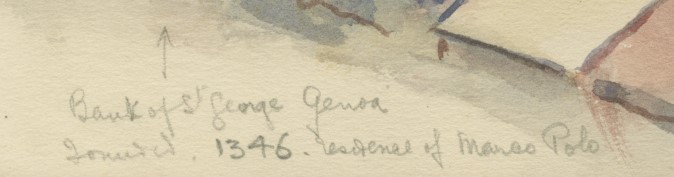

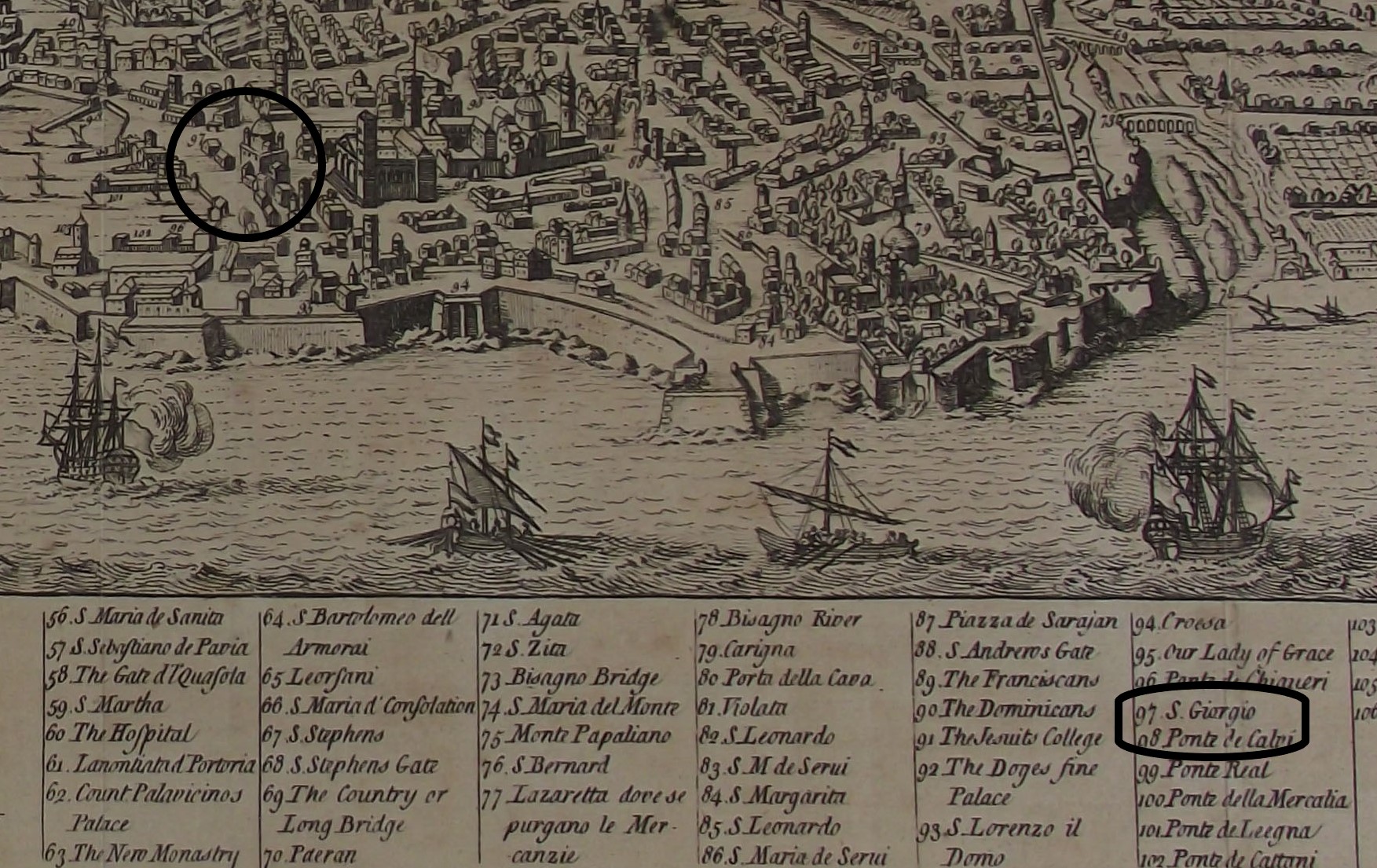

One painting in particular was very intriguing. On the painting Admiral Chambers wrote, “Bank of St. George, Genoa, founded 1346. Residence of Marco Polo.” I love going to historic sites, so my first thought was how cool would it be to visit Marco Polo’s house. An old bank though? Surely Genoa has all kinds of other significant sites that are much more fascinating. Turns out, I was wrong.

I did a quick search and could not find the house in Genoa. I found an 18th century reconstruction of Christopher Columbus’ house, but nothing for Marco Polo. My first big mystery: what in the world was Admiral Chambers writing about? I decided I should look up Polo’s history: when was he in Genoa? Polo adventured to China with his father and uncle starting in 1271 when they went to visit Kublai Khan. Polo became an ambassador for Khan, and spent 17 years traveling to various Asian countries and reporting back about their cultures. He returned to his home in Venice (not Genoa) around 1295 after being gone for 24 years.

In 1298 Polo participated in the battle of Curzola between bitter rivals Venice and Genoa, where the Genoese captured him and reportedly held Polo prisoner in the public palace-turned-prison, built between 1257 and 1260. It is there that he reportedly told his adventurous stories to another prisoner, Rustichello da Pisa, who published them in a book titled Il Milione. Thus Polo became famous.

Fun fact: the palace-turned-prison eventually became the judicial offices for the port, then it became the home of the Bank of St. George! Admiral Chambers wasn’t talking about two different buildings, he was talking about one! It was pretty obvious once I realized that. But then, what in the world was the “founded in 1346″ date? My second big mystery.

According to Giuseppe Felloni, who has spent several decades cataloging and studying the archives of the Bank of St. George and published Genoa and the History of Finance: A Series of FIRSTS? in 2004 (you can read the book here), the bank was officially founded in 1407 and opened on March 2, 1408. The documents from the first meeting are widely published. However, the 1346 date that Chambers references has a history of its own.

The 1822 book A General View of the History and Objects of the Bank of England by John McKay refers to the Bank of St. George being founded in 1346 on page 90. By the 1840s and into the 1860s many books reprinted Joseph Addison’s 1701 description of the Bank of St. George, but then add the 1346 date as a footnote.

This date most likely refers to one of several mergers of the compere, or a type of state debt. Comperas were loans to the state of Genoa, which provided the loaners certain rights to control the city’s revenue sources to create a return on their investment. In his book, Equity Capital: From Ancient Partnerships to Modern Exchange Traded Funds, Geoffrey Poitras describes comperas as a “type of early Italian capital association of a corporate character.”

Henry Harrisse’s 1888 book, Christopher Columbus and the Bank of St. George, describes several of these compere mergers on pages 53-54, specifically a merger of 27 comperas in 1346. These mergers eventually led to the creation of the Bank of St. George in 1407. However, Felloni’s research in chapter three of his book states that the mergers took place in 1303, 1332, 1340, 1368, 1381, and 1395.

My best guess is that someone in the early 1800s tried to find the history of the bank, found some information about the mergers, and ran with the 1346 date from when a compere was formed that eventually formed into the Bank of St. George in 1407. Over time, that date was published so many times that it stuck.

But why might someone in the early 1800s want to research the history of an old bank? Because that’s when the bank closed, nearly 400 years after it opened! Napoleon invaded Italy in 1805 and put an end to the Bank of St. George.

Felloni details the legacy of the bank in his book, writing that from 1408 the Genoese began considering new methods of banking. They were the first innovators of public debt, government bonds, sinking funds, double entry and public accountancy, and eight other economic practices that are common today. You can read the updated 2017 edition of Felloni’s book here. Felloni has made it his mission to update the economic histories that give the credit for these innovations to the Bank of England, or discuss Genoa’s role in the economic history but either mention the bank in passing or not at all.

The Bank of St. George was the first modern bank, the brief residence of Marco Polo where his international fame began, and today the 760 year old building still stands as the offices of the port authorities that have occupied the building since 1903. And now I want to go tour the bank!

To search the archives of the Bank of St. George and learn more, visit here http://www.lacasadisangiorgio.eu/main.php?do=home