Earlier this year we conducted a survey of all the small metal objects waiting to be conserved. We assessed the condition of each, took a photo, and changed solutions. We also slated some objects for x-radiography.

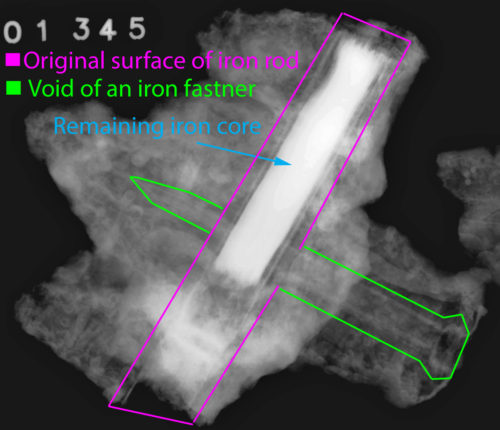

There are three reasons these particular objects were singled out. First is to determine the condition of the object. When artifacts are submerged in seawater they are covered in a cement-like aggregate called concretion. This is a mixture of metal corrosion products, sediment, and sea life, including mollusk and corals. Concretions can be a thin hard shell scattered across a surface or entirely encase a group of objects in an amorphous lump. By x-raying these concretions we can:

- Identify the objects inside. Due to their different densities, we can distinguish between metals and organics, or even cast and wrought iron.

- Use the x-ray as a road map to excavate the concretion and avoid accidentally hitting an object.

- Determine the condition of the objects inside. Sometimes an object completely deteriorates, leaving a void in place of the artifact. We can drill a hole in the concretion, fill it with resin, and deconcrete around this replica of the object. The original may be lost, but now have a 3D copy of the artifact.

The second reason is safety. The USS Monitor was outfitted with weapons and mercury-filled engine instruments. All of these were potentially dangerous during their life aboard the ship, however they still can be hazardous even today. With this in mind, we x-rayed a glass tube in order to determine if it contained mercury. The tube may have been from a pressure gauge and is entirely coated in corrosion and concretion. If it contained the heavy metal, it would look like a glow stick on the x-ray due to the metal’s density. We did not detect mercury, but will still handle it with care.

The third use for x-rays is to gain more information about the object. By looking at an x-ray we can better understand its manufacturing and assembly without taking it apart. We can use this information in several ways:

- To determine if an object can be taken apart. An x-ray not only gives a how-to guide for disassembling an object, but also shows us the object’s internal condition. If it is too fragile, we may decide to treat the object as it is.

- To provide archaeological information about the wrecking of the ship. Documentation is vital when excavating a site or disassembling an artifact. As the state of the wreck and objects change we may lose critical information. These images create a permanent record of how the objects were set at the point of sinking. For example, the valve below is open. We can add that information into the greater picture of how the engine room equipment was staged at the time of the sinking.

- To provide technological and manufacturing information of ship components. X-rays can reveal things like difficult to read maker’s marks and internal fittings. We can use these insights to research where these parts came from and how they were constructed.

X-radiography is a great tool for us in the lab. It provides unique information about artifacts that we would not know otherwise. Not only does it answer questions about technology and the archaeology of the ship, but it has stopped a number of headaches over the years when looking at a concretion and wondering just where to start.