Hello everyone! As promised, this week’s post is all about the metals survey. This was a great opportunity for me, having joined the conservation team in December, to have an in-depth look at our collection.

For the last month and a half, Will, Mike, and I have opened over 300 containers as we examine all the small inorganic artifacts awaiting conservation. The majority are iron and copper alloys, but there are other metals and glass as well. The purpose of the survey is to assess individual artifacts’ conditions and create a record of the current state of the collection. This allows us to prioritize. If something is very fragile and actively corroding, we want to focus on it, before it declines further. Inversely, if something is in great condition we want to treat it before we lose any more information. All of our organic material underwent a similar survey in 2015. As we check-in periodically, it establishes a timeline for the object throughout its life in storage. Conservation takes time. It is important to keep an eye on the whole collection, especially those which aren’t in active treatment.

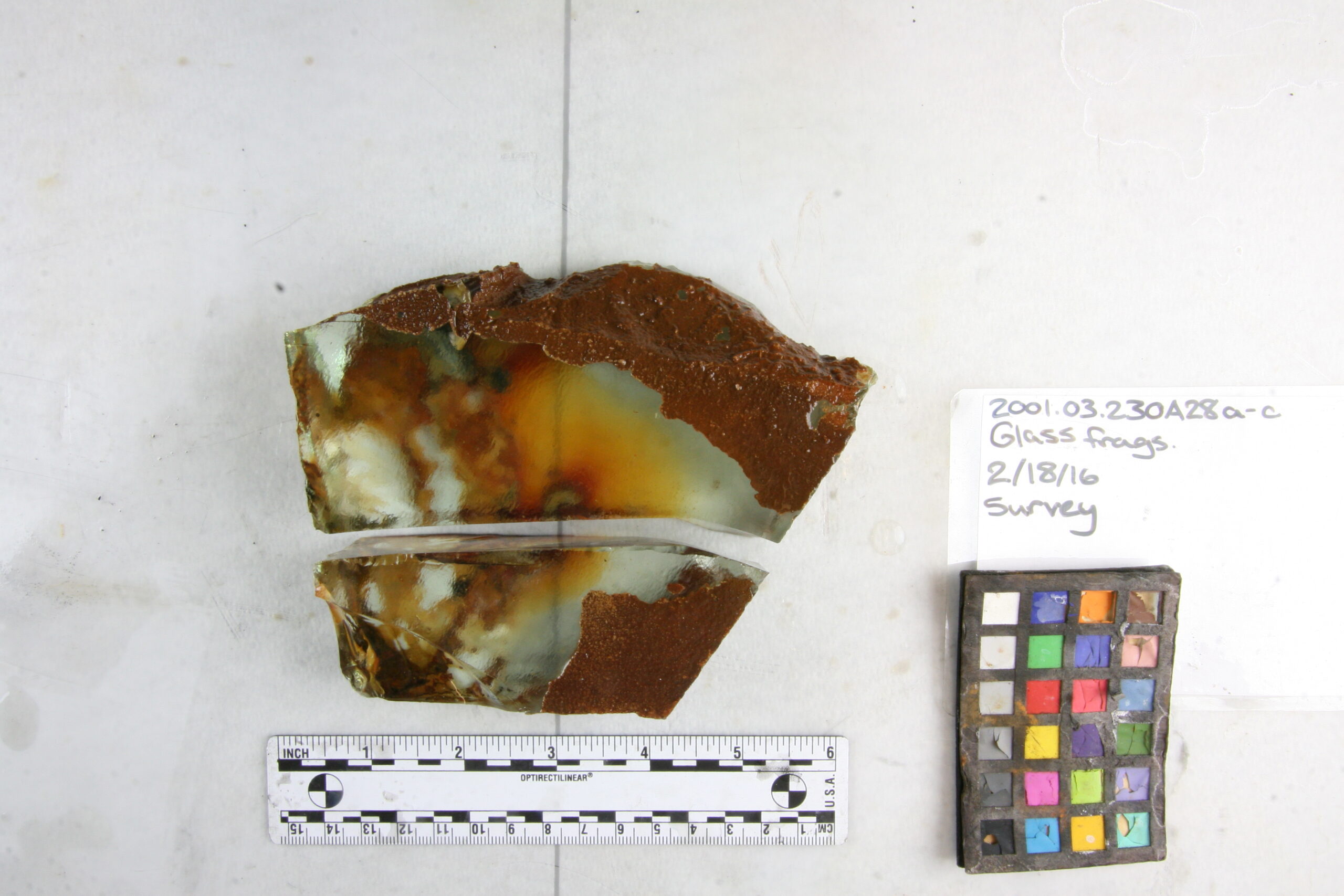

The survey consists of two parts; documentation and cleaning. Each artifact is photographed and condition reported. Some are slated for x-rays. Then we gently rinse it and put it in fresh solution. I have had the joy of playing with the Ion Chromatography (IC) machine which Elsa introduced in the last post. It’s a wonderful piece of equipment which helps measure how many chlorides (the bane of a conservator’s existence!) are in the old solution. By keeping a record of chloride levels as we change solutions, we know where an object is in its desalination process. One of the most important treatments in conservation of marine artifacts is the removal of salts. If chlorides remain in the artifact after it is dry, the corrosion process could continue and the object will need to be retreated.

The survey has been very helpful for me to learn more about the project. As we pulled out the more intricate engine components, Will explained their purpose and placement within the system. The engine room machinery is daunting at first, but I am wrapping my head around 1800’s steam technology.

Mike walked me through another important part of the project; the recording system. Paperwork may seem boring but proper documentation is the foundation upon which collections stand. Every single component has its own number and can be traced exactly back to where it came off the engine or turret. This is vastly important for a project which is disassembling large artifacts only to reconstruct them years later. As conservators, we strive to be ethical in our care of artifacts. Recording all treatments and keeping up-to-date records on the condition and location of objects is standard procedure.

Overall, the survey was a success. One of the thing that caught my attention was the varied state of preservation among the artifacts. It’s a testament to Ericsson’s design and the craftsmanship of the builders that fastenings have remained water-tight for 150 years under the ocean and look brand-new in places. But best of all was when I photographed a tiny, twisted lump of resin. After a few seconds out of solution it started to smell like pine. How incredible, after all this time, just how much these artifacts can still tell us.

Look out for the survey’s next phase in the coming months: Fun with X-radiography!