Hello! As this my first blog at The Mariners’ Museum and Park I will introduce myself. My name is Molly McGath and I’m the new Analytical Chemist here at the museum. I imagine some of you might be a bit surprised at the idea of a chemist working in a museum. I do many different kinds of chemical analysis of museum objects, including chemical identification and characterization, exploring deterioration mechanisms of objects, and studying the short-term and long-term behavior of conservation treatments. To give you a better idea of what my job is like, I’ll share a project I worked on right after starting.

First the Tale. . .

Conservator Paige Schmidt brought me a question about an object she was treating. She wanted to know whether the handle of this knife (see image below) was made from baleen. So I started the process of chemical analysis.

In a time before plastic. . . can anyone imagine that?. . . objects, that today are made out of plastic, were made from other materials. Handles, combs, boxes and many other objects were commonly made from animal-products. These include horns, turtle shells, and baleen among other materials.

Time for Chemical Analysis

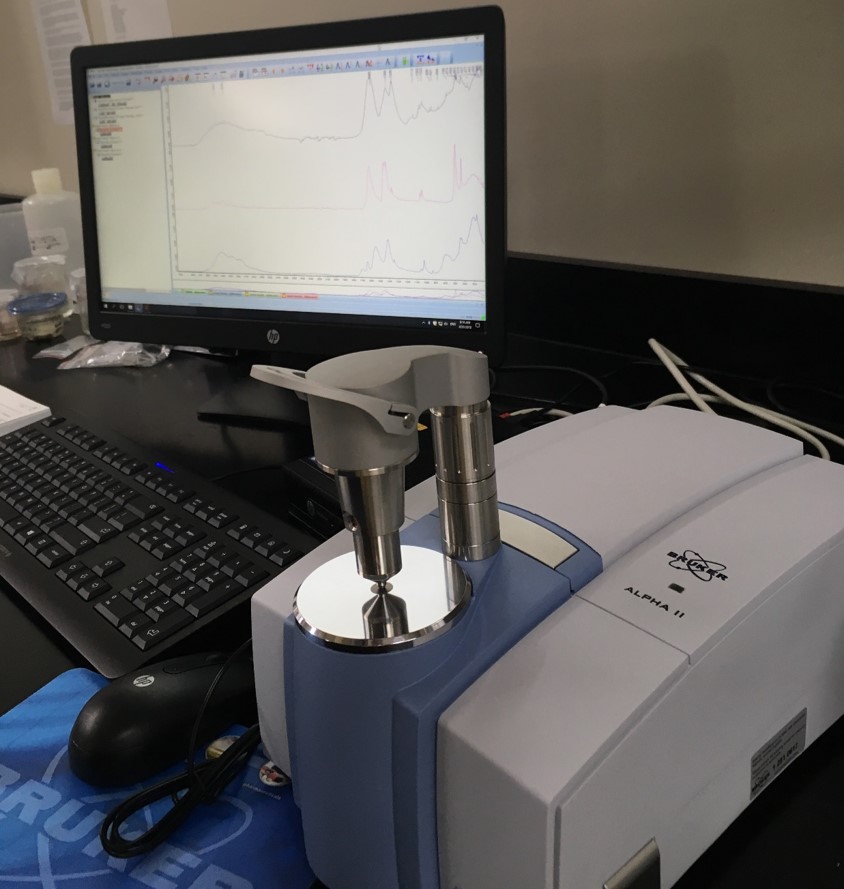

To answer Paige’s question, I fired up the brand new infrared spectrometer. (For technobabble fans it is an attenuated total reflectance-Fourier transform infrared spectrometer or ATR-FTIR).

This awesome instrument was purchased with partial funding from the National Maritime Heritage Grant Program which is administered nationally by the U.S. Department of the Interior along with the Maritime Administration of the U.S. Department of Transportation, and in Virginia, by the Department of Historic Resources (which is also partially funding my position with matching dollars from The Mariners’ Museum and Park). It allows us to do non-invasive chemical analysis on many different types of museum objects.

I was able to test the knife’s handle using this equipment. It provided a spectrum that I tried to match to references. And I found that we had no reference for baleen.

Enter the Whale. . .

Or rather, enter a large bristle (tooth) from a whale.

Credit: The Mariners’ Museum and Park

Whale bristles, or whalebone, are the “teeth” of the whale. At lengths of 6-10 feet, these bristles were used in many different ways by many different industries.

An aside:

Not being biologists of any kind, Paige and I had questions regarding how to talk about baleen. Baleen acts as the “teeth” of a whale. But baleen is chemically more similar to hair than to mammalian teeth. So, we were in a quandary. We found many references calling baleen “whalebone”, which we thought may be confusing as chemically this material doesn’t resemble bone. We also found references that called individual baleen pieces “bristles”. So instead of “whalebone” or a baleen “tooth”, we decided to refer to it as a baleen “bristle”.

As the bristle in the collection has not been made into an object, I can say for certain that it is baleen. I used our handy ATR-FTIR to analyze the spectrum from the baleen bristle. And I compared it to the knife handle’s spectrum.

And it matched! Well. . . Sort of? The baleen matched the knife handle with about an 84% spectral match. This means that the spectrum is “consistent with” baleen.

However, the material that the knife handle was made from had been processed from its original state!

Baleen, when heated, becomes plastic or mold-able. In the science game there are a whole category of these materials that we call thermoplastics. These thermoplastics were heated with steam, or boiled, and then pressed/manipulated into a variety of shapes. Think back to the beautiful tortoise shell comb for an example of this. However, processing materials in this way can alter the chemistry of the material. I expect that the spectrum of a processed material to differ from an unprocessed one.

Another aside:

Baleen and hair consist of the same type of protein: keratin. I decided to run a sample of hair to compare against both the knife handle and the baleen sample. The hair had about a 60% match with the knife handle, and an 88% match with the baleen. This pointed me back to the idea that the processing of the handle really changed its spectrum.

At the End of the Day. . .

We still have questions. This is the beauty of science, and of working in a museum. Every answer brings more questions. What does processing do to baleen’s IR spectrum? How does processed baleen age in comparison to unprocessed baleen? What do the spectra of other baleen objects look like?

There are many more questions, from many more objects that I am pursuing. And I will be sharing some of these stories here.