The mysterious continent of Antarctica has fascinated explorers and dreamers for centuries. Through the possibilities of scientific discovery or just the challenges that come with the hardship of survival there, the siren call of the ice has beckoned many. But there were four intrepid explorers who never asked, or even wanted, to go there. From January 1934 to February 1935 they braved the cold, storms and whims of their fellow explorers while doing their part to support the expedition.

In 1928 when Admiral Richard Evelyn Byrd, Jr. announced his intention to go to Antarctica and explore the continent by airplane, he quickly found financial backing for his quest from wealthy Americans and private citizens. Among his many accomplishments, Byrd was famous as the navigator on a 1926 trip that he and pilot Floyd Bennett claimed was the first airplane flight over the North Pole. This trip to Antarctica would now make him the first American explorer there since Charles Wilkes’ U.S. Exploring Expedition in 1840. The successful 1928-1930 expedition launched a public revival of interest in Antarctica and more interest on Byrd. Along with the scientific research, the team established Little America base on the Ross Ice Shelf and Byrd made the first airplane flight over the South Pole.

But when Byrd began looking for funding for a second trip planned in 1933-1935, he discovered that it was very difficult trying to convince potential investors that additional geographical exploration and scientific research was necessary. Especially when the country was still hampered by the Depression era climate. Byrd’s solution was to raise the money through partnerships that would not only pay for and market the expedition, but also make money through products and publicity. Paramount Films, CBS Radio, General Foods and other companies signed on. Their investments in money and supplies gave them the opportunity to film the expedition, sponsor radio programs with interviews and updates from the team, and produce souvenirs. Byrd got his second trip to Antarctica and everyone involved got worldwide publicity.

Another idea Byrd had was to ‘make dairy history’ by working with the American Guernsey Cattle Club to take three cows with him to Antarctica. It wasn’t entirely a publicity stunt since Byrd reportedly drank two or more quarts of milk a day and disliked the more easily transported powdered variety. The dairy industry had an active advertising campaign to convince the public that milk was a healthy and necessary food for adults as well as children. Byrd’s actions would further reinforce that belief.

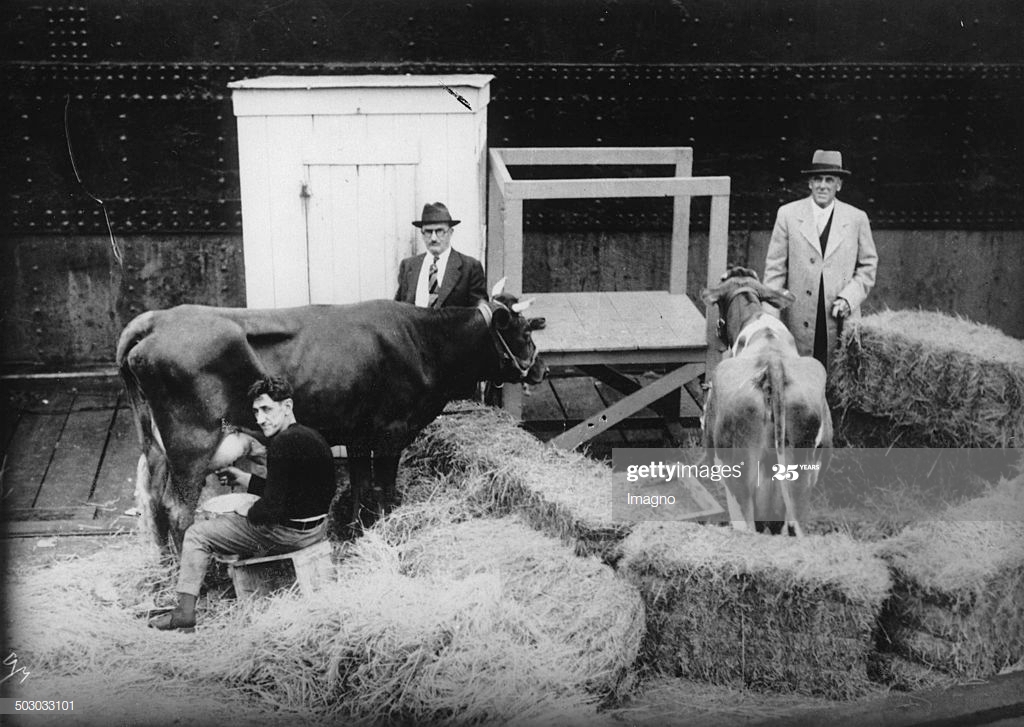

The three cows came from prominent dairy farms and were loaned to Byrd for two years. The plan was that a cameraman from Paramount would travel with them to film their experiences for a movie titled “Guernseys Discover Antarctica” and upon their return, the cows would be exhibited around the country at fairs and exhibitions with all the expected media fanfare. At the end of the two years, they would return home to their pastures.

Foremost Southern Girl from New York, Deerfoot Guernsey Maid from Massachusetts and Klondike Gay Nira from North Carolina were the chosen bovines. Klondike was the last one chosen because Byrd wanted a pregnant cow who would give birth to the first cow born in Antarctica. Their supplies were donated by investors and their care was entrusted to ship’s carpenter, Edgar F. Cox, who also owned a small dairy farm.

The cows traveled on the RUPPERT JACOB in a special shelter built on the deck and then moved inside as the ship approached colder climates. They seemed to have no problems adapting to the voyage, but their more than 15,000 mile journey couldn’t have been very pleasant, especially when their trip was delayed due to severe weather. The delay would also end up thwarting some of Byrd’s plans because Klondike gave birth to her bull calf about 250 miles before they reached the Northern Antarctic Circle. Edgar Cox had spotted icebergs just a couple days before the birth, so he named the calf Iceberg.

When they arrived in Antarctica on February 3, 1934, Deerfoot was the first cow to step foot, or hoof, on the continent of Antarctica. Not sure how impressed she was with her achievement, but Southern Girl was definitely not a fan of the ice and snow. As soon as her hooves touched it, she spun around and headed up the ship’s gangway, making it to the top before the crew managed to coax her back down. The cows and the explorers had to travel 2.5 miles to their temporary home at Little America base and all the cows made their way on foot, except for Iceberg who traveled by vehicle and was then carried by Edgar.

A large tent served as their temporary home on the ice but it didn’t stop the cows from suffering frostbite. At night they froze to the ground and each morning they had to be pried off the ice so they could stand up. As soon as a heavily insulated barn was made from thick bales of hay with a raised platform for them to stand on, they were moved and their frostbite began to heal. But for Klondike, the move came too late. The frostbite damage caused large wounds on her skin that never fully healed. On December 16, 1934 Edgar had to make the difficult decision to euthanize and bury her. Because the explorers had grown so fond of their little herd, the other cows were moved elsewhere and the men held their hands over their ears so they wouldn’t hear the gun. Klondike was buried not too far from Little America.

The cows produced about three times as much milk as the expedition could possibly drink even though their milk production gradually decreased as time passed. Iceberg grew from a calf to a strong bull. And then it was time to head back north. In February of 1935, the two cows and bull were loaded back onto the JACOB RUPPERT, all in good health. Although public interest in the expedition had waned as their time in Antarctica lengthened, their return to Virginia in 1935 was met with much excitement. As planned, the cows traveled across the country, ‘meeting’ dignitaries, state and local officials. They went to Washington DC, Chicago and even attended a luncheon at the Hotel Commodore in New York where Iceberg “grunted vociferously” throughout the speeches. Byrd described their reactions, saying their expressions were the same melancholy look “with which they contemplated the whole expedition.”

And afterwards? The cows returned to their farms. Iceberg was sent to the home of his mother, Klondike Farm in Elkin, North Carolina where he was said to have arrived with ricketts, a Vitamin D deficiency so severe that he wasn’t ‘considered of much use as a cow’. He was gradually nursed back to health and he was still a tourist attraction there in 1947. Iceberg also became an American folk hero, complete with a medallion made in his honor. Deerfoot never lost the thick winter coat that she had grown in Antarctica. She went back to Deerfoot Farms in Massachusetts where she lived until 1942. Foremost Southern Girl returned to Emmadine Farm in Hopewell Junction, New York where she lived in pampered comfort among a herd of 350 Guernsey cows who were provided for under an endowment set up by famous merchant J. C. Penny, the owner of the farm.

Thanks for reading!