…but I thought I would volunteer an annotated list of some of the maritime history books that I have found myself pulling off the shelf (again and again) for reference during my twenty-year tenure at The Mariners’ Museum and Park.

The Story of Sail by Veres László and Richard Woodman (Chatham Publishing: 1999) is a dense volume of over 1000 scale drawings of (you guessed it) sailing vessels. A wealth of details about sails and rigging are complemented with great drawings of the vessels themselves all backed by a thorough bibliography.

Dictionary of Wars by George Childs Kohns (revised edition Facts on File, Inc.: 1999) is a bit of a throwback in the Age of Wikipedia. Concise synopses provide starting points and a quick reference for the wars, conflicts, and major campaigns in history as well as providing a standardized means of identifying iterations of multi-generational conflicts (I’m looking at you Anglo-French Wars). The most useful part of the book is a geographical index of conflicts organized chronologically (the Netherlands goes on for pages).

Speaking as a Francophile, it pains me to admit the best book for its time period is Nelson’s Navy: The Ships, Men, and Organization: 1793-1815 by Brian Lavery (revised edition Naval Institute Press: 2012). Details, details, and details pack this large and heavy tome. What were the worldwide squadrons of the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars? Listed! Who were idlers? Of all types! How much room was a common seaman given to sling his hammock on a ship-of-the-line? Not much! Author Brian Lavery is Curator Emeritus of the National Maritime Museum in the United Kingdom, so it shouldn’t come as a surprise that another of his works bear mentioning. I used Ship Models: Their Purpose and Development from 1650 to the Present (Press of Sail Publications: 1995) to shape the organizational structure of the Ship Model Gallery at The Mariners’ Museum.

In contrast to the decidedly adult-reading level of Lavery’s works, my go-to reference for the European Age of Contact is a book intended for a school-age audience. The First Ships Around the World by Walter D. Brownlee (Cambridge University Press: 1974) is a MERE fifty pages managing to pack a wealth of information about the ships sailing from Portugal and Spain during the 16th Century. This slim book is part of the formidable Cambridge Introduction to the History of Mankind series.

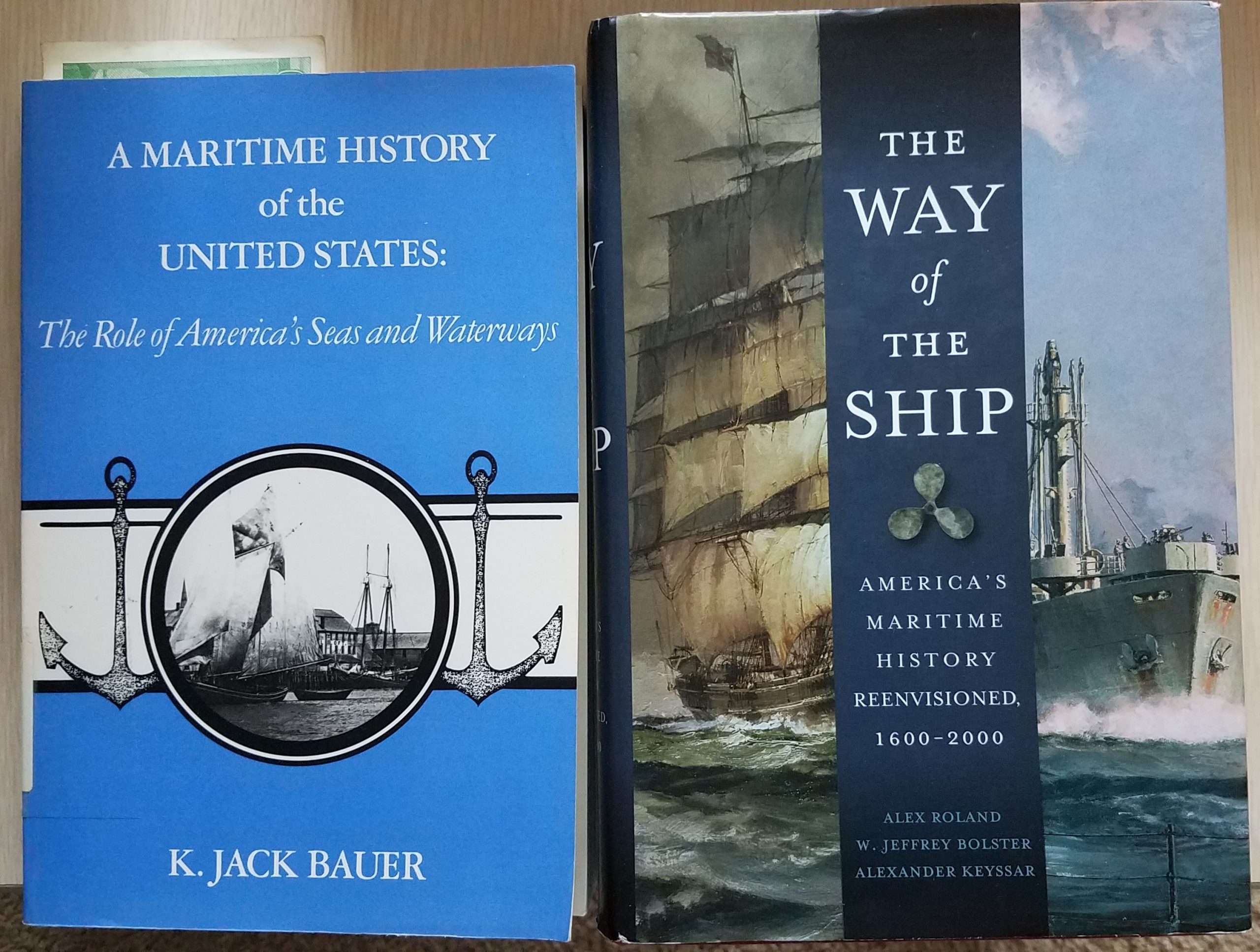

Four works comprise my American history ready reference. A Maritime History of the United States: The Role of America’s Seas and Waterways is the posthumous work of K. Jack Bauer (University of South Carolina Press: 1988) and serves as a good counterpoint to the newer The Way of the Ship: America’s Maritime History Reenvisioned, 1600-2000 by Alex Roland, W. Jeffrey Bolter, and Alexander Keyssar (John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2008). Named individuals dominate the former while labor relations informs the latter.

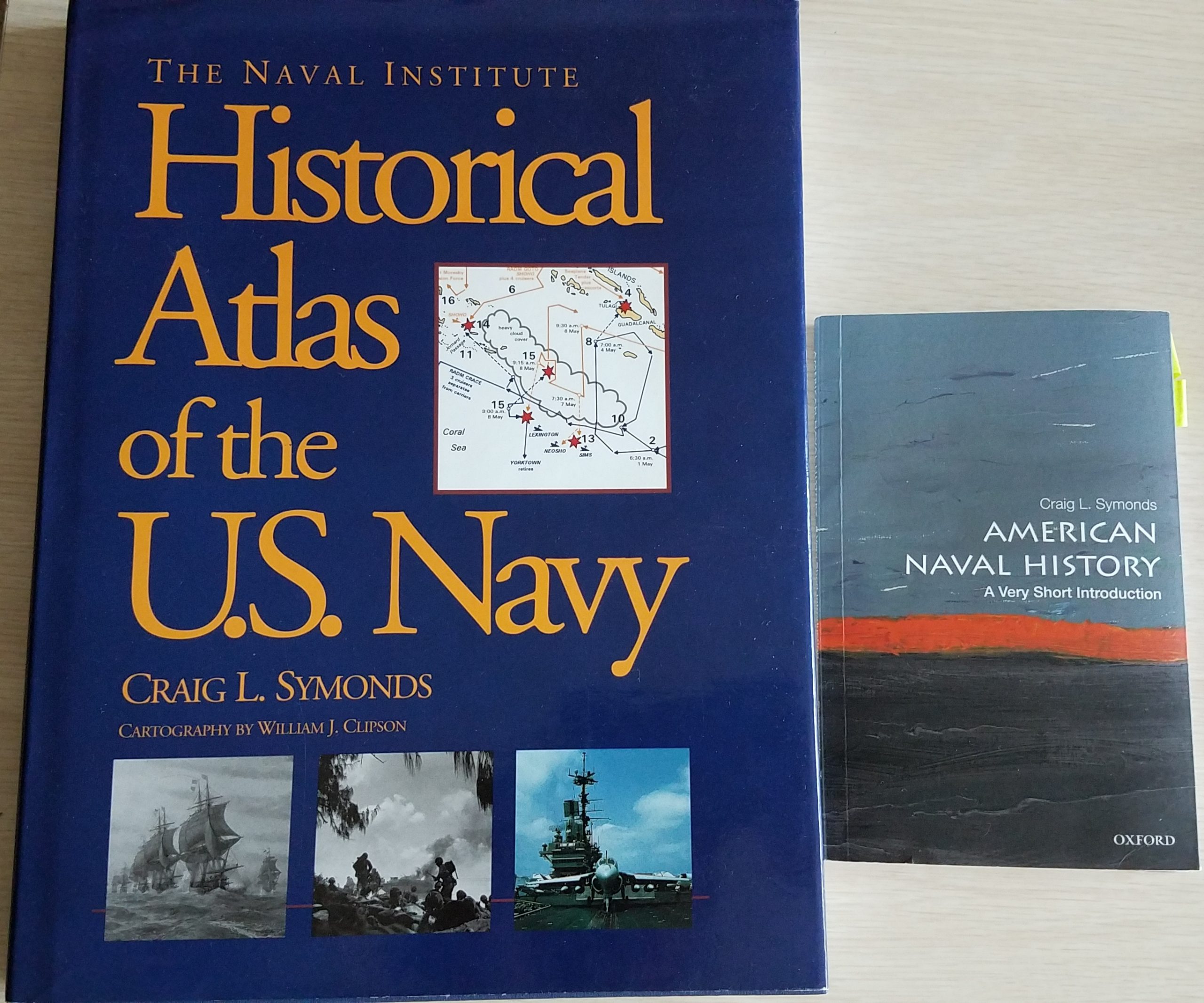

My US Navy history go-tos are both by Craig L. Symonds. The Naval Institute Historical Atlas of the U.S. Navy (Naval Institute Press: 1995) is a great complement to the pocket-sized American Naval History: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press: 2016). Symonds’ thesis of alternating contraction and expansion of the Navy is a persuasive one.

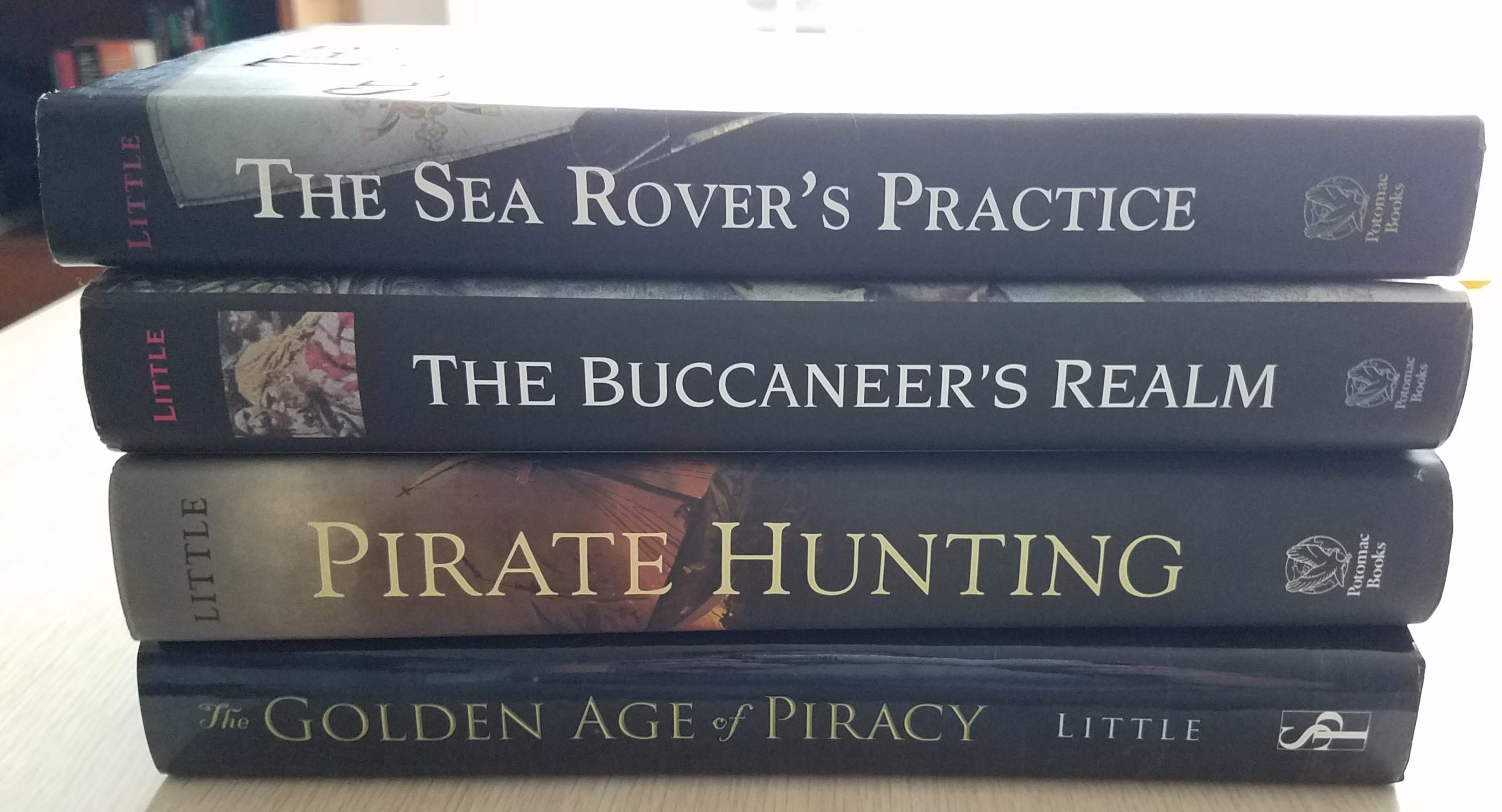

Finally comes the pirate books. This is no small section of total shelf space but the works of Benerson Little qualify as desert island books for me (perhaps having been marooned for some transgression). The Sea Rover’s Practice: Pirate Tactics and Techniques, 1630-1730 (Potomac Books, Inc.: 2005), The Buccaneer’s Realm: Pirate Life on the Spanish Main, 1674-1688 (Potomac Books, Inc.: 2007), Pirating Hunting: The Fight Against Pirates, Privateers, and Sea Raiders from Antiquity to the Present (Potomac Book Inc.: 2010), and The Golden Age of Piracy: The Truth Behind the Pirate Myths (Skyhorse Publishing: 2016) combine the author’s experience in the US Navy with examinations of primary sources and experimental archeology to create accessible and thought-provoking guides to piracy.

Perhaps providing this list is giving away part of the secret to my durability at the Museum. So be it. Science fiction author John Brunner summed it up best, “…you don’t have to know everything. You just have to know where to find it.”