It began a few years ago with a handful of old, unlabeled photos. Images of workers who placed the bricks and the cinder blocks for the Museum’s walls and also installed the statues on Lions Bridge and in the Park. They were literally part of the very foundation of our Museum. Then the questions began. What were their names and their stories? Why were they so important to our Museum, but we didn’t know who they were? What we found, and are still finding, has evolved into one of the most interesting, impactful, heartbreaking, joyous, and eye opening projects we have ever worked on. A project we named “Hidden Histories.”

The earliest beginnings of the project actually started from several other initiatives. A quest to gather as much information about our Park and grounds as possible, and a look forward to our 100th Anniversary coming up in 2030. The emphasis on our Park is part of a long term project focused on issues like conservation, sustainability, ecology, preservation and the history of the area. This work has helped with the formation of our new Park Department which was announced earlier this month. The 100th Anniversary project is taking a look back at our history and also a look forward to see where we are headed in the future.

Both projects led to the discovery of photos showing the men who did the construction on our Museum and Park. As well as a number of images showing members of our Museum team dating from the 1930s and beyond. The photos are part of our Institutional Collection that documents what happens here. They include famous visitors, parties, exhibitions, large artifacts arriving, personnel photos, and just about anything else related to our day to day activities. While we knew what types of photos we would find in the collection, we didn’t anticipate finding out what we didn’t have. The men’s identities and a realization that despite our Museum’s focus on inclusion and connections within our community, we hadn’t made a connection with ourselves. In the 91 years since the first of those photos were taken, we hadn’t made a connection with the men who were the very foundation of our success. And the hard truth is that because of who they were, no one in the 1930s thought it important enough to label these images and ensure they would be known by their names and faces. The time was way overdue to correct this.

For a while, the images of the Black men who built our Museum remained anonymous, despite our efforts to try to identify them. All we really had to go on was that they worked here. So that is where we started. Using newspaper archives, genealogy sites, obituary archives, grave registries, and books, we tried a lot of blind searches. Different combinations of words and phrases, hoping that we might get a hit. We tried Newport News, Mariners’, Museum, maritime, worker, employee, Black, and any other words we could think of that might fit. Sometimes single words and sometimes combinations. Sometimes using the same words over and over again, just in a different order. And slowly, we began collecting a handful of names. But we still couldn’t link the names to the photos.

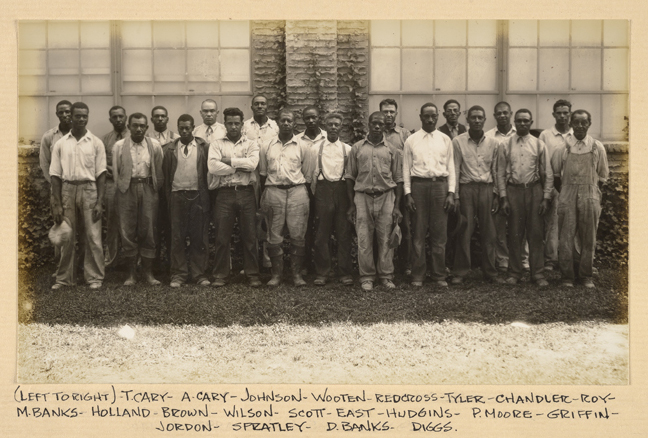

Then last summer we found a posed group photo from the 1930s showing 21 Black men standing in front of the building on our property that the Newport News Shipyard had been using for hull model and hydraulic testing. We thought that it might be possible that several of the men in the group might also be in one or two of the construction photos. Since many of the Shipyard employees worked on various projects at the Museum in the early days, that could add a new level to our mystery. If the men weren’t actual Museum employees, but all employed by the Shipyard, would that complicate our task or make it easier?

In December, along with the photo and information searches, another search was taking place in our Library Archives in another Institutional Collection, this time one that contains early museum records. There, one of the most significant pieces to our puzzle was found. A copy of the same group photo in front of the test building, but this time with a caption that identified the men as Museum employees and giving their last names and a few initials. The photo was quickly scanned, emailed around the Museum and there was a time of great rejoicing among the researchers. Although we did wonder how we were going to find the correct Mr. Brown, Mr. Moore, Mr. Wilson and the other men whose names were, and still are, popular names in the local area. Especially when we didn’t even have first initials for most of them. And so the “blind” searches with many different search terms started again.

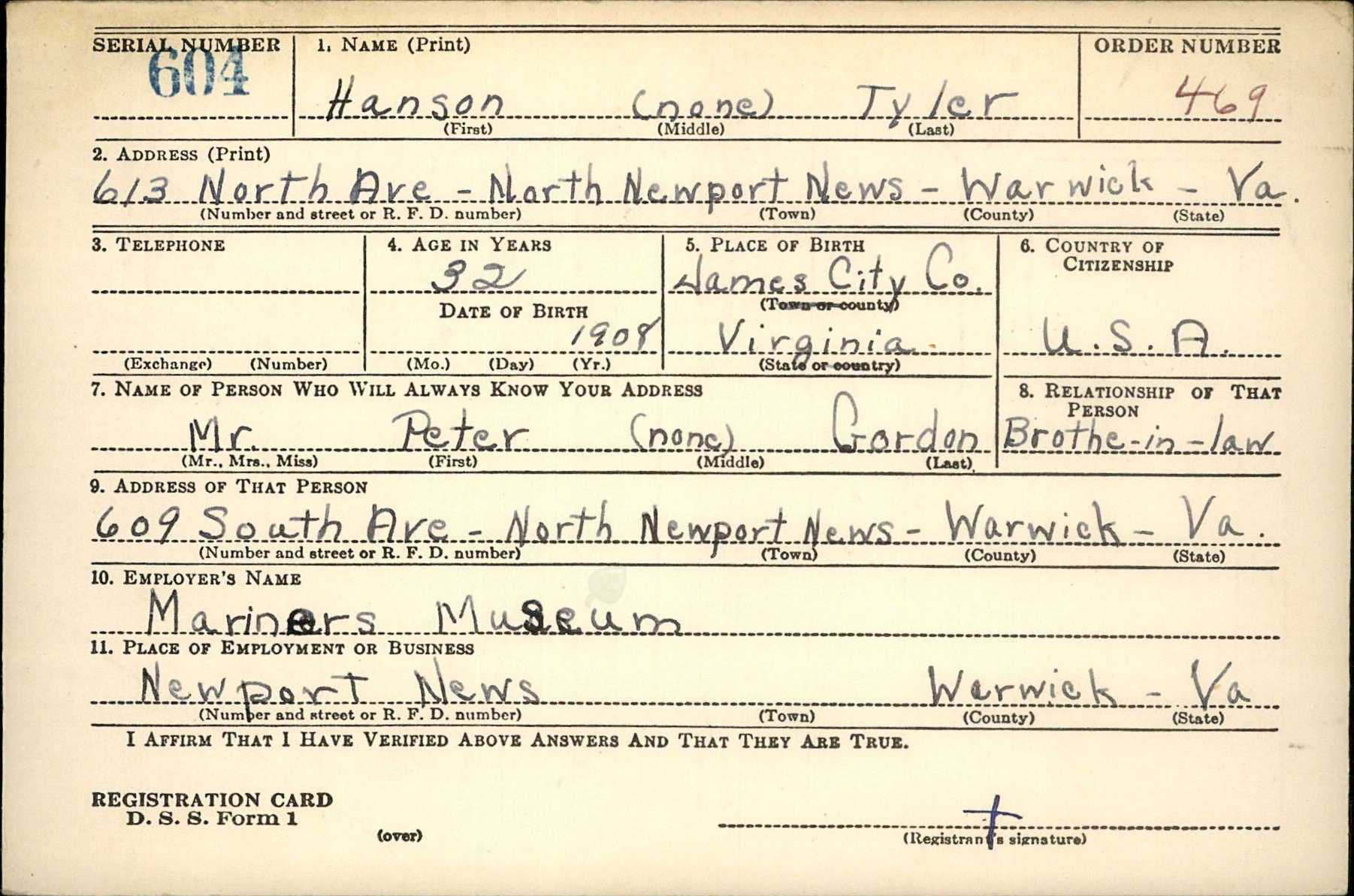

But this time, we were matching names to the photos! Matching WWI and WWII draft registration cards which listed employers and the census records and newspaper articles. Comparing obituary photos with the images of the much younger men in our photos. And finding first names, middle names, and even some nicknames. And yet another treasure soon turned up in the Archives. A three page carbon copy document containing the names of early employees which gave us some additional names and some more first names for the men in the group photo.

By January 2021, the Hidden Histories project had its name and we were expanding our connections to both the men who were our foundation and to the community. The decision was made to make Hidden Histories a community project. For Black History Month in February, we concentrated our programming on our former teammates, explaining the project and sharing what we had found. Asking the public for help identifying the men we hadn’t yet identified and to share stories of their family members who had worked at the Museum over the years. Our community responded with offers to help in our searches and sharing information. Our group of researches was expanding both inside and outside of the Museum. And as a result, we got to experience the humbling sight of a granddaughter touching the very wall her grandfather helped build.

From the very beginnings of the Hidden Histories project, we all knew this was personal. These men were part of our Museum family and the stories we were discovering were having a profound effect. Seeing page after page of census records with entire neighborhoods out of work during the depression years. Countless men reporting their job during that era as “pickup laborer”, doing whatever work they could find to feed themselves and their family. Mothers, daughters, and sisters working as maids and domestics, some of the only work available to them. Aware that they were doing the same work their ancestors were once forced to do. Death certificates with conditions that might have been survivable with proper medical care. Signatures on draft cards that are merely an “X” mark because the men couldn’t read or write. A father who tried to defend his son, but was injured himself and later died.

We have been like proud parents when children’s names were listed in the paper because they made the honor roll at their school. Rejoiced when a newspaper praised a son for his talent on his High School and College football fields without first mentioning the color of his skin. Possibly the first time that had ever happened. And felt sorrow when we realized that a young bride probably died alone in a Tuberculosis sanatorium hundreds of miles away from her family who may not have had the means to visit her, much less be there to say goodbye. Because that was the only sanatorium in Virginia for Black patients.

Will we share everything we find during our searches with the public? No. Some things, if found, are meant to be private and those will only be shared with the families of our former teammates. That’s the right thing to do. But we will continue to search for our Hidden Histories and continue to shine light on these stories. Because we, no matter who we are, what color our skin may be, or what we do in life, have more things in common with each other than we may realize. Sometimes it just takes a bit of searching to awaken us to them.