Every museum goer has encountered warnings about touching artifacts, but have you ever wondered just how damaging that contact can be? I think we would all agree that leaping a barrier and picking up a vase is a definite bad idea, but what about resting your hand on a chair or poking a polar bear specimen? The truth is even the lightest touch can cause harm.

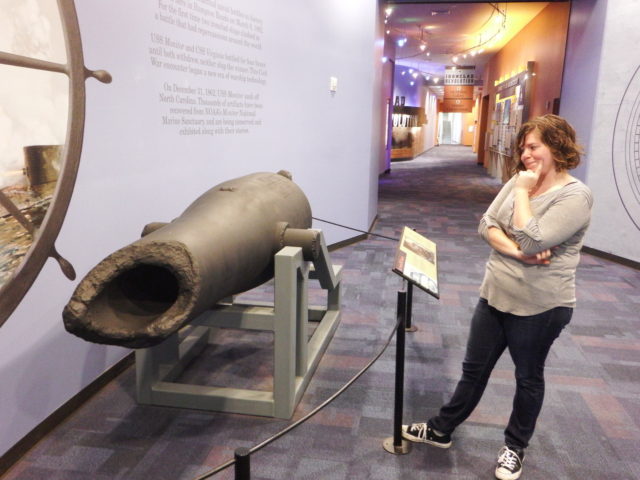

Last week I took a break from dry ice cleaning to work on the “Virginia Gun,” an IX-inch Dahlgren shell gun which sits at the entrance to the Ironclad Revolution exhibit. It was recovered along with the USS Merrimack by the Confederates and was used aboard the renamed CSS Virginia during the Battle of Hampton Roads (1862). It is a fascinating object that draws a crowd. Unfortunately, it also tends to draw wandering hands. My job was to remove greasy fingerprints from the side of the barrel. This got me thinking about how we protect objects and how although we have “do not touch” signs around the museum, visitors might not understand why this is such an important rule.

We understand the temptation to touch objects. People are tactile. Touch is used to gather information. People want to know how something is made or if it’s a replica. That physical connection creates an emotional bridge to the past. Additionally, there are times when visitors touch things because they don’t actually realize something is real. People are so used to seeing cannons or furniture at historical sites, that visitors forget they are artifacts in their own right and not props. Any of these reasons can lead to damage from handling.

So what actually happens when someone touches an object? The easiest damage to picture is the kind you hear in the news. Million dollar vases shattering because they’ve toppled off their stands or parts being snapped off a machine when someone tries to turn a handle. These things do happen, but thankfully they are fairly uncommon. Most people understand that picking things up or exerting force on museum pieces is inappropriate, however even light touches can pull hairs out of taxidermy, rip delicate fabrics, or scratch surfaces. Keep in mind that most of the objects you see on display have had a long, loved life before they reach the museum. They are old and delicate, having lost a lot of their original strength. Chairs can no longer support people and metal may no longer be structurally sound. The Monitor propeller is actually one of the more fragile artifacts in the exhibit due to graphitization, a process in which iron leaches out of the artifact and only the carbon shell remains.

Fingerprints are also incredibly damaging. They contain natural oils, salty sweat, and foreign dirt which is happy to make the leap from fingers onto unsuspecting surfaces. This is why fingerprinting is so useful in forensic cases. You leave behind these contaminants on every surface you touch. Even if it is a fabric, and you cannot “pull” a print off of it, you are still leaving these residues behind and the longer they remain on surfaces, the harder it is to remove them.

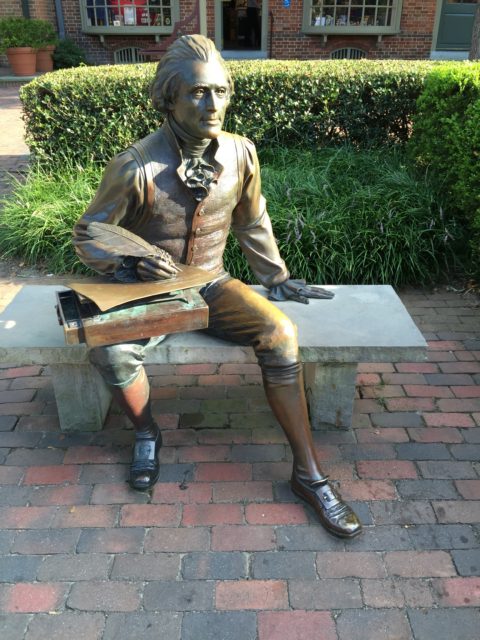

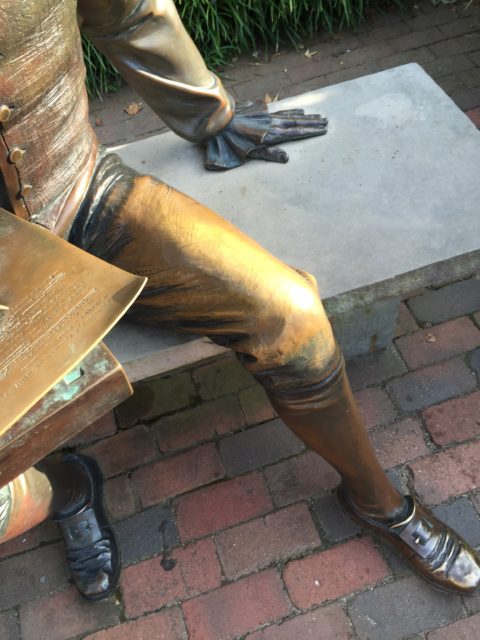

Fingerprint residue will dull or tarnish the surfaces of polished metal. I have seen a perfect thumbprint etched into the surface of a historic coin which can now only be removed by abrasion. Alternatively, repeated touching will locally polish the metal, removing the patina and exposing the site to oxygen and further corrosion. Wood, bone, and ceramics will absorb the grease and grime from hands which causes staining. It is easy to see this effect on white marble statues. Spots where people have rubbed appear grubby and grey.

How do you know then, if it is okay to touch an object? Sometimes it is perfectly acceptable, and even encouraged, to touch things. There are a number of contemporary works of art which incorporate visitor interaction into the performance of the piece. Statues in public spaces, like the one of Thomas Jefferson which sits on a bench in Williamsburg, VA may also encourage interaction. It was installed with the understanding that people would sit on his lap or put an arm around his shoulders while taking photos.

There are also times when something is considered historic and protected, but is still an object in everyday use. Religious items are a great example of this. A statue located in Japan shows how wood absorbs oils and dirt from hands, but rubbing it is an important custom and therefore is an allowed practice.

Additionally, most museums have working collections. You may have visited a museum and a staff member let you hold an object. We love being able to bring objects out from behind the traditional glass case display. These artifacts have been chosen because they can withstand being passed around. They can either be cleaned or the anticipated damage and wear is minimal. One example of this is the iron hull plate in the Monitor exhibit. It is a robust artifact with a protective coating on it which can stand up to the thousands of hands that touch it every year.

Most of the time, however it is not appropriate to touch a display. Museums employ many techniques to prevent this. We rely on people’s knowledge of museum etiquette to keep a respectful distance. This is common in art museums. Visitors can stand near a painting or statue on a pedestal, but we’ve been conditioned not to touch. However, if it’s fragile or there will be a lot of interest in it, a deterrent may be employed. Security guards, barriers, and signs encourage people to stand at an appropriate distance. Of course this is also not full proof. The Virginia Gun’s railing sits low and close to the artifact, putting it in reach of even our smallest visitors.

One of my favorite options is alternatives. In the Monitor gallery, our wonderful Exhibit Design department built replicas of the forward deck of the Virginia and the officers’ quarters on the Monitor. Visitors can walk through these and envision life aboard the ships. They can also touch screens to play videos of reenactors. By having interactive exhibits with clearly defined hands-on activities near artifacts enclosed in barriers, it reinforces the idea that the two are different and should be treated as such.

Most important is education. This blog post is not meant to chastise, but to encourage better understanding. Museums safeguard collections for education, research, and inspiration for now and well into the future. We share a responsibility to treat these objects with respect and ensure that they are maintained for generations to come. Even minimal damage adds up over time and can severely alter objects. And that is why we don’t touch the artifacts.

So next time you’re in The Mariners’ Museum see if you can spot the different ways we protect the objects. Spend time playing with the interactive games. And take as many photos as you want (for personal and educational use). Share them with us on Twitter and Facebook! But just keep in mind, we have a shared responsibility to protect these artifacts. And one of those ways is to limit touching them.