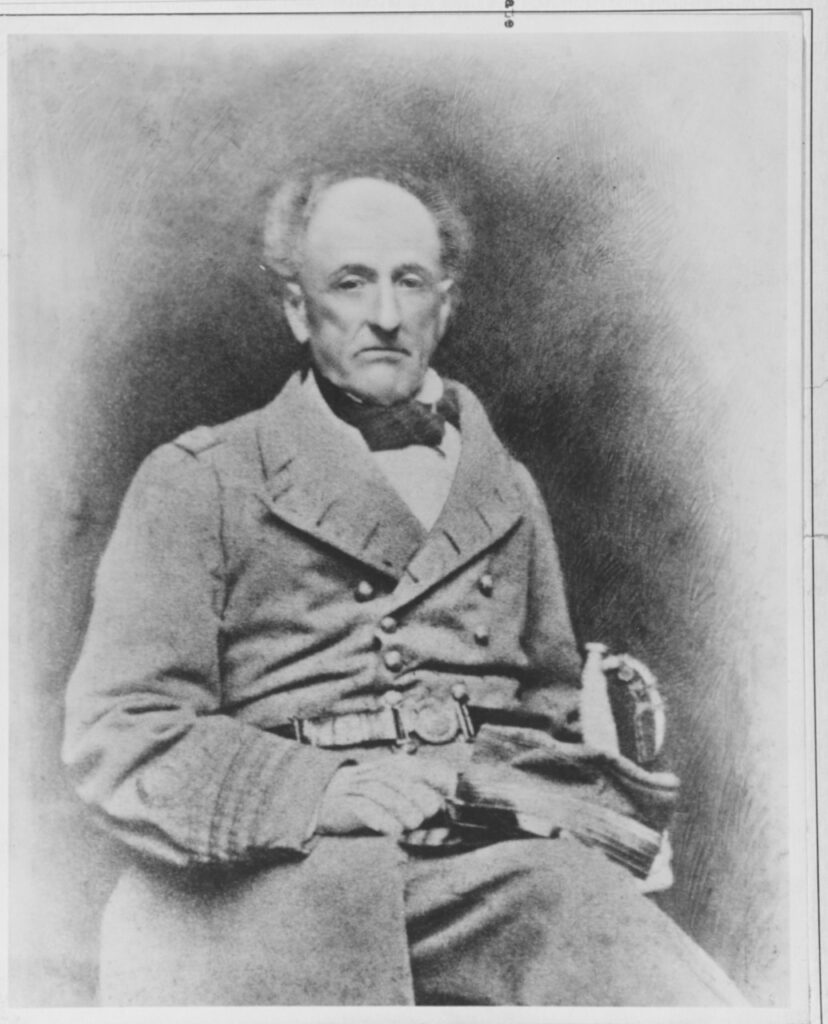

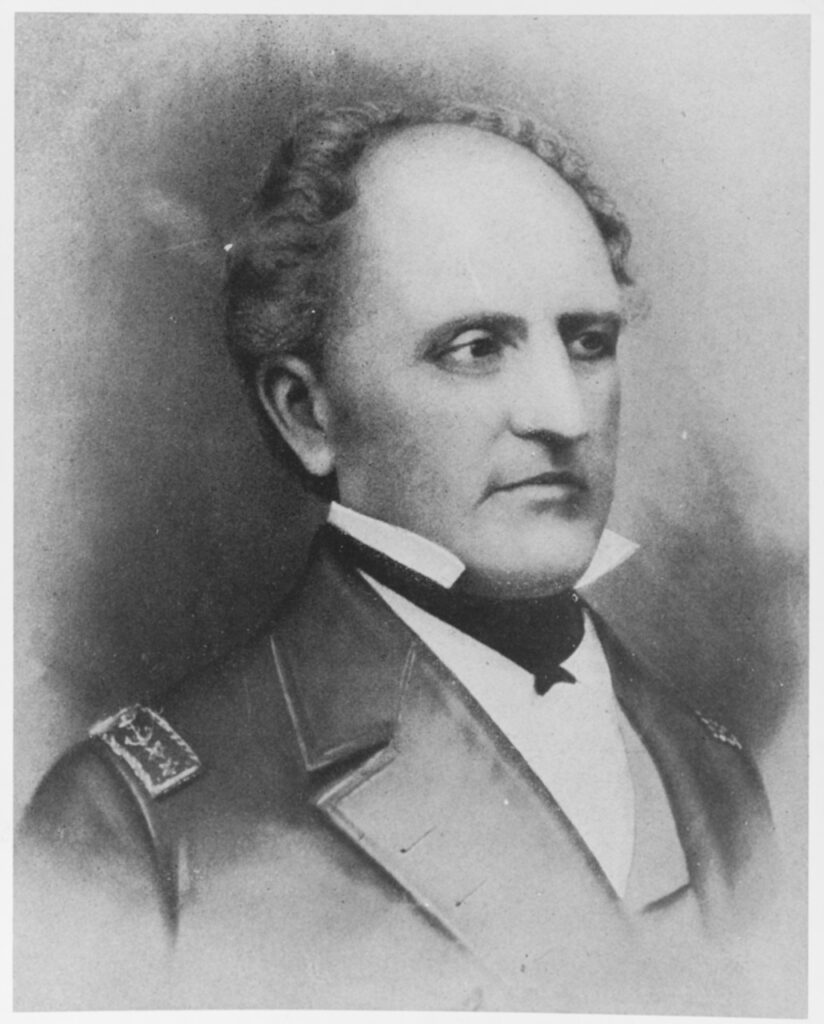

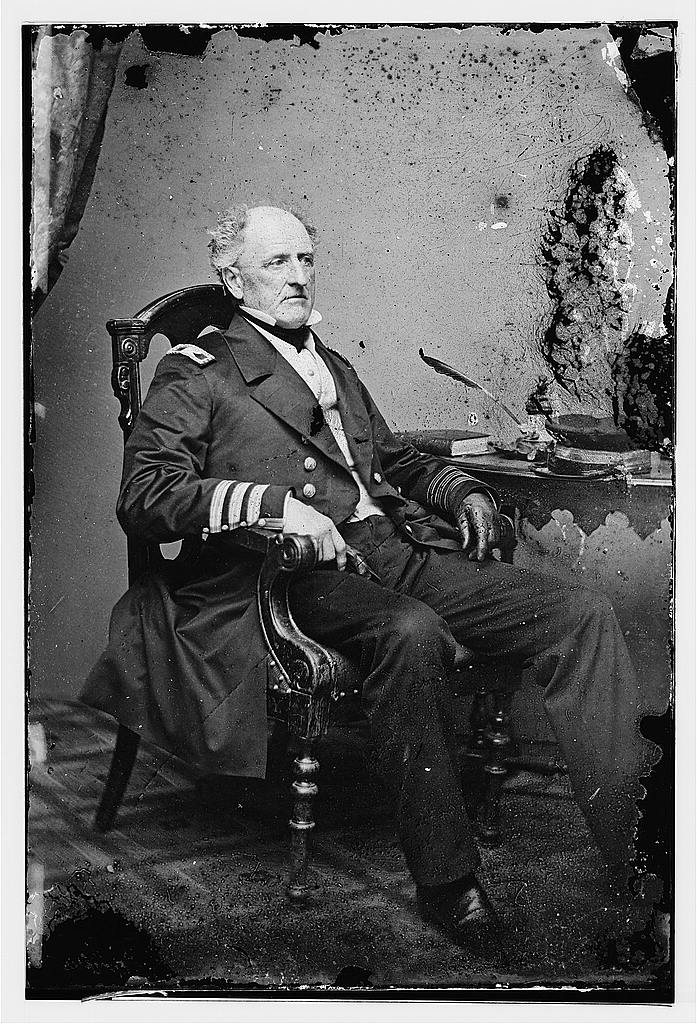

Able, courageous, and experienced, Franklin Buchanan was perhaps the most aggressive senior officer to join the Confederate Navy. His strategic flair, discipline, and heroic qualities made him respected and admired by all those around him. “A typical product of the old-time quarter deck, as indomitably courageous as Nelson, and as arbitrary,” Lieutenant John Eggleston described Buchanan. “I don’t think,” he added, “ the junior officer or sailor ever lived with nerve sufficient to disobey an order given by the old man in person.”1 Ashton Ramsay thought Buchanan to be “one of grandest men who ever drew a breath of salt air.”2 Consequently, Buchanan was Stephen Mallory’s only choice to take the Confederate ironclad into battle.

A SUCCESSFUL CAREER

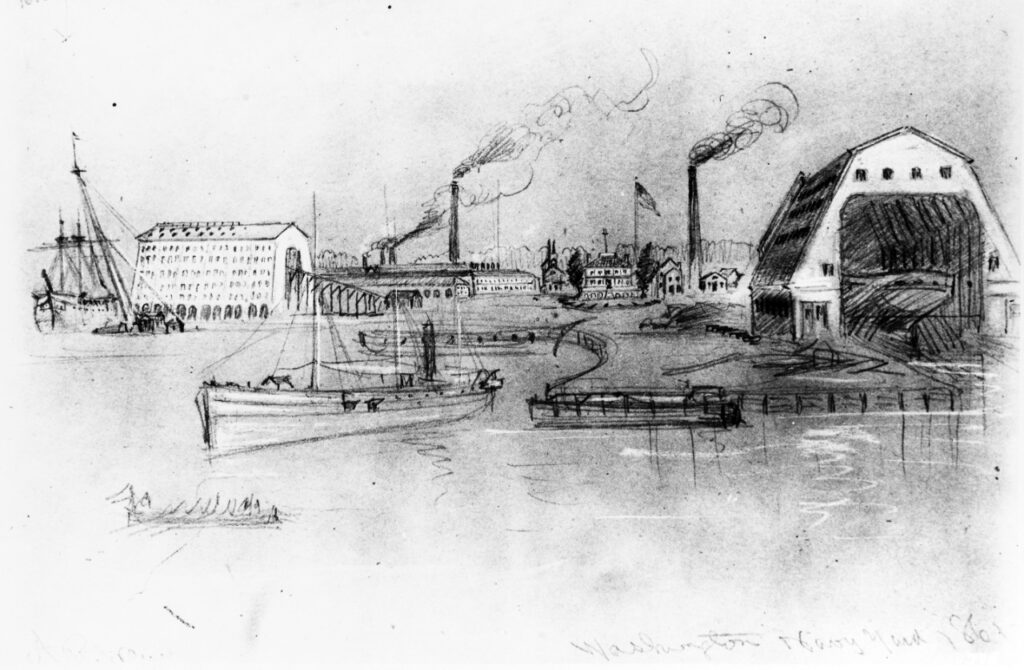

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, on September 17, 1800, Buchanan was appointed a midshipman in 1815. He served on numerous warships during his early years in the US Navy. In 1845, Buchanan submitted a plan to establish the US Naval Academy and was named its first superintendent. Buchanan fought with distinction during the Mexican War as commander of USS Germantown. He was detailed as captain of the flagship USS Susquehanna during Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry’s 1852 and 1853 expeditions to Japan. Promoted Captain on September 14, 1855, he commanded the Washington Navy Yard until April 20, 1861.

SOUTHERN LOYALTIES

Like so many other Southern officers serving in the prewar U.S. Navy, Buchanan was torn between his loyalty to the Union and his devotion to his home state during the secession crisis. “I am as strong a Union man as any in the country,” Buchanan wrote. “Union under the Constitution and laws and as to the stars and stripes I have as strong a loyal feeling for them as anyone who was ever born; I have fought my country’s enemies under the glorious stripes, and will do again when occasion calls for my services, but as to fight my own countrymen and relatives under it I never can. I am no secessionist,” Buchanan added, “and did not admit to the right of secession, but at the same time I admit the right to revolution.”3 Buchanan proudly displayed his fidelity to the Stars and Stripes during the wedding of his daughter, Nannie, to Lieutenant Julius Ernest Meiere, USMC, on April 3, 1861. The reception was held in the Washington Navy Yard headquarters. “The house was everywhere festooned with the American flag, even to the bridal bed,” remembered David Dixon Porter. Even though a number of suspected disloyal officers were present, President Abraham Lincoln attended the ceremony and even cut the wedding cake. The turmoil of succession touched the gala when “Buchanan’s daughter, Elizabeth Taylor, then fifteen years old, refused to shake hands with Mr. Lincoln, at first who called her a little rebel and finally won her over with bonbons and the charm of his personality.” A little more than two weeks later, David Porter reflected, “the Commandant, including his new son-in-law, resigned their commissions and left the Washington Navy Yard to take care of itself.”4

Buchanan’s Southern connections immediately placed him under suspicion by the Lincoln administration. “I was, by reliable friends, put on my guard as respected … Buchanan,” Gideon Welles wrote, as he was “being courted and caressed by the Secessionists.” Buchanan, however, remained loyal to the Union until the April 19, 1861 Baltimore Riots. Believing that his native state of Maryland would soon secede, Buchanan resigned his commission on April 20, 1861. When Maryland did not leave the Union, he sought reinstatement. “I never was an advocate for secession,” Buchanan reflected to a friend. “I am a strong Union man … I have had a horror of fighting against the ‘stars and stripes’.” He wrote to Gideon Welles, “ I am ready for service,” noting that he hoped to be assigned overseas so that he would not have to fight against the South. “Your name,” Welles replied, “has been stricken from the rolls of the Navy.”5

Even though he was courted by the Confederacy, Buchanan retired to his estate near Easton, Maryland, until September 1861. Then, after transferring all his property to his family, he went south and was commissioned a captain in the Confederate Navy on September 15, 1861. Mallory, despite some questions by other naval officers as to Buchanan’s fidelity to the South, appointed Buchanan as head of the Office of Orders and Detail. Buchanan administered this important office with tremendous imagination and supervised the publication of the Confederacy’s Navy Regulations. He developed a system of merit promotions to replace the seniority system. Franklin Buchanan’s work and commitment to the Confederacy made him one of Mallory’s trusted advisors.

COMMAND OF THE JAMES RIVER DEFENSES

On February 24, 1862, Buchanan was named flag officer in command of the James River naval defenses. This appointment was Mallory’s effort to circumvent the old seniority system by placing Buchanan in command of CSS Virginia. The new ironclad became Buchanan’s flagship and he was determined to take Virginia as quickly as possible.

THE POWER OF IRON OVER WOOD

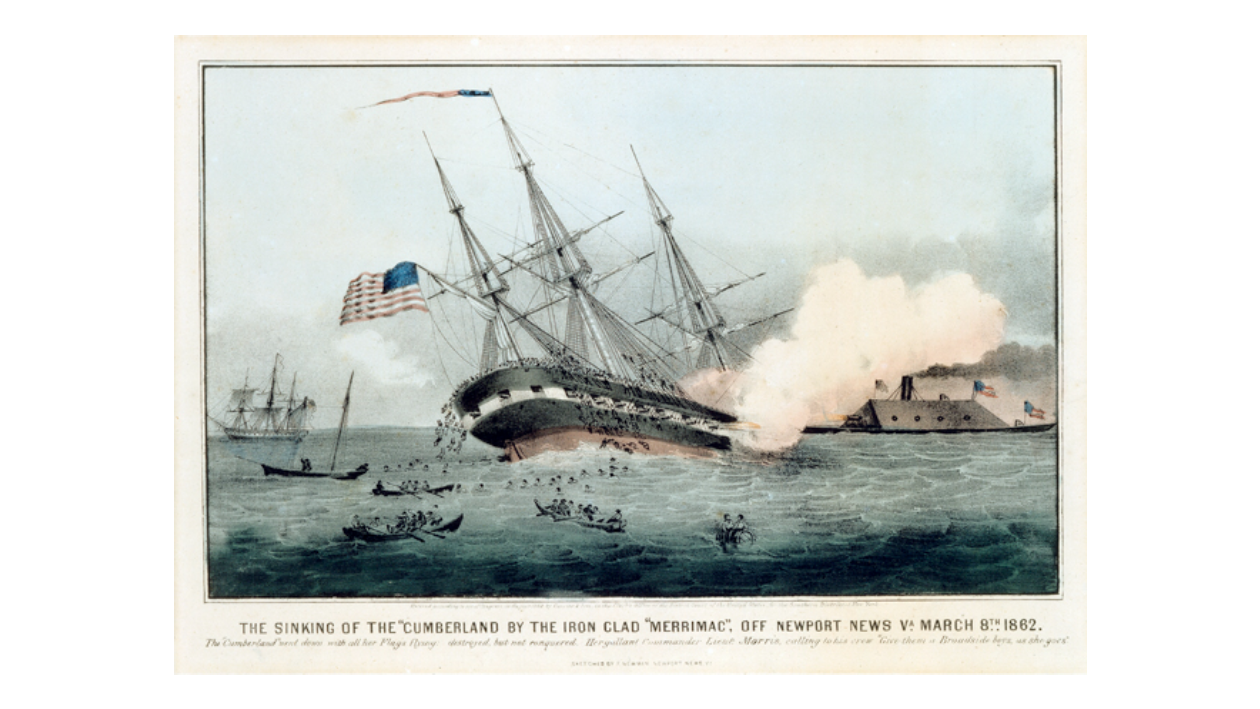

He endeavored to gain the cooperation of Major General John Bankhead Magruder to attack Camp Butler at Newport News Point. Magruder, however, rejected the concept, and Buchanan proceeded with his own plan. On March 8, 1862, Buchanan rammed and sank USS Cumberland, destroyed USS Congress, sank two transports, captured one transport, and damaged one gunboat and two frigates. It was the Confederacy’s greatest naval victory; however, Buchanan was unable to fully enjoy his success. While supervising the destruction of the USS Congress, Buchanan climbed atop Virginia and exchanged rifle fire with Union troops on the shore. Buchanan was wounded in the hip by a bullet that grazed his femoral artery. Consequently, he turned the command of Virginia over to his executive officer, Lieutenant Catesby ap Roger Jones.

March 8th, 1862.” The Mariners’ Museum and Park, 1933.0460.000001.

PROMOTION AND NEW ASSIGNMENT

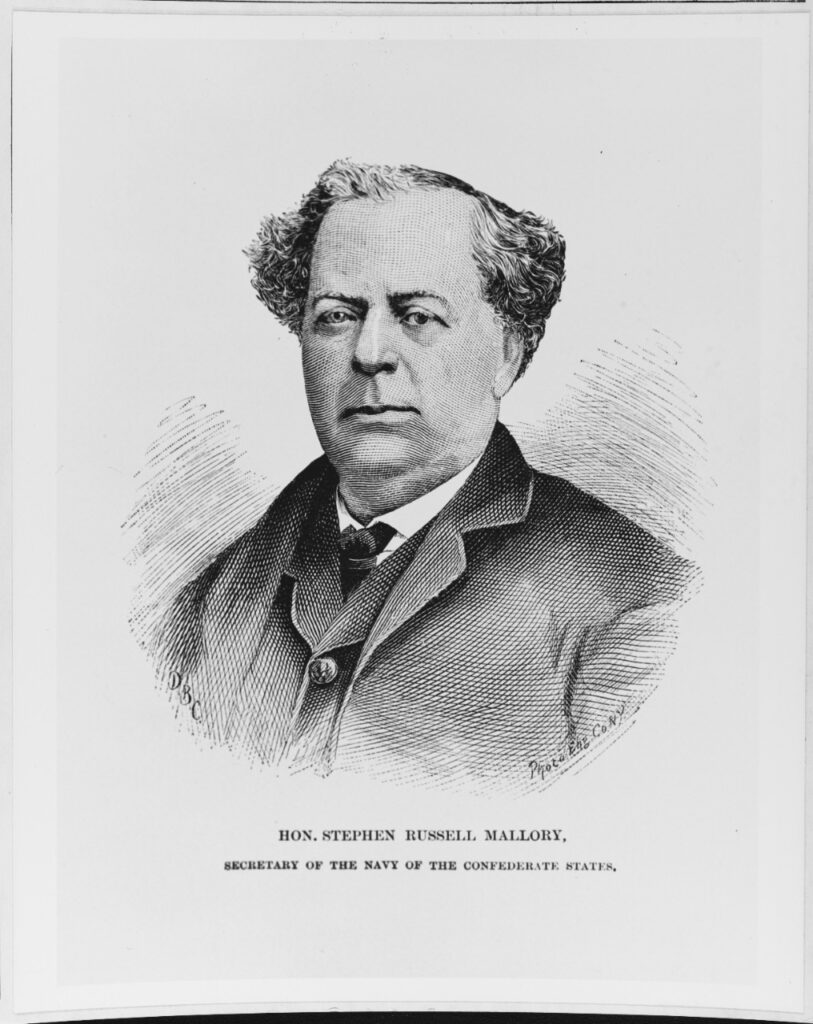

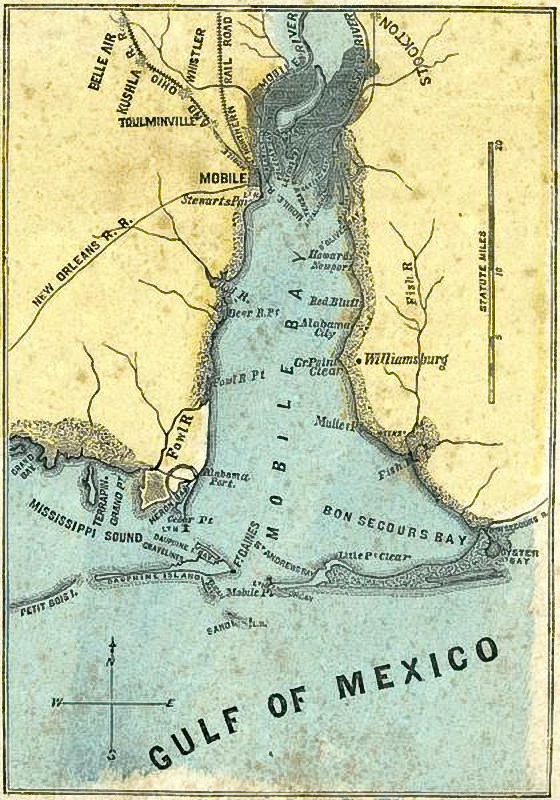

Buchanan’s wound was very painful and healed very slowly. Two months passed before he could walk without crutches, and the wound continued to bother him throughout the summer. He convalesced first in the Portsmouth Naval Hospital and then completed his recovery at Greensboro, North Carolina. On August 21, 1862, Buchanan was appointed as the first Admiral in the Confederate Navy. Mallory then selected him to command the naval defenses in Mobile Bay, Alabama. Mobile, once New Orleans had fallen, was one of the most important ports for blockade runners along the Gulf Coast. It was paramount to the Confederacy to keep this port open for commerce. Mallory knew that Buchanan was the person with dynamic strategic flair as one officer wrote ‘Buchanan is a man and a Commander.’6 The Confederate Secretary of the Navy hoped that the Confederate Admiral would be able to use the seven different ironclads that were under construction at Selma, Oven Bluff, and Montgomery, Alabama, to break the blockade and, perhaps, liberate New Orleans and the lower Mississippi River.

MORE IRONCLADS

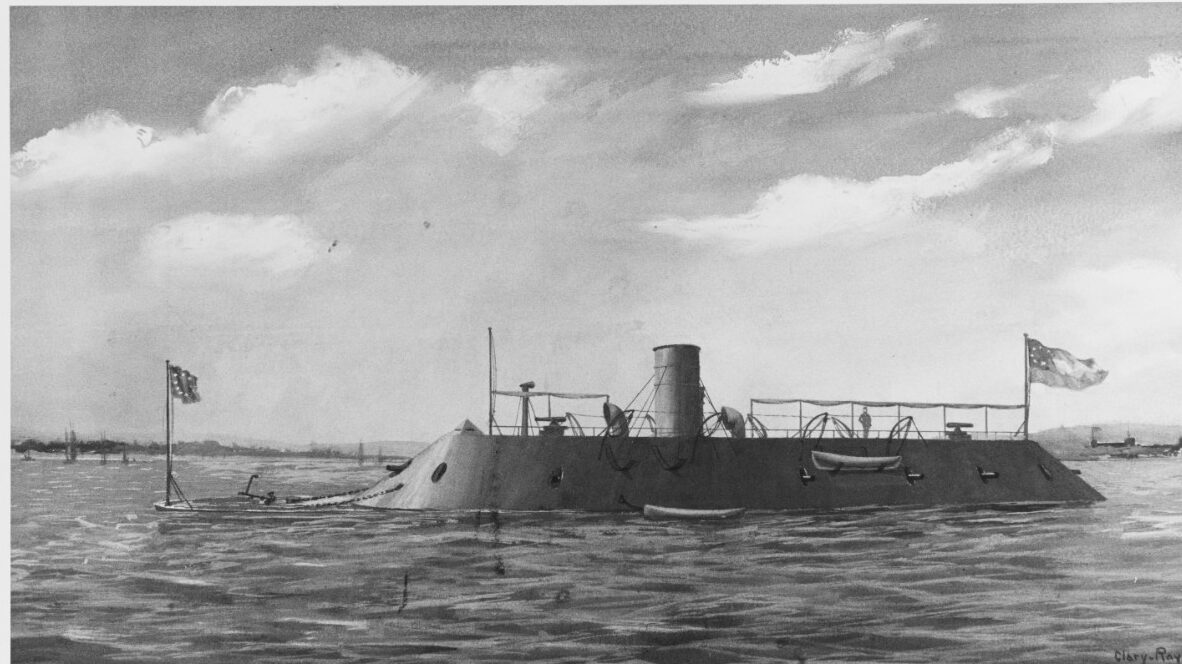

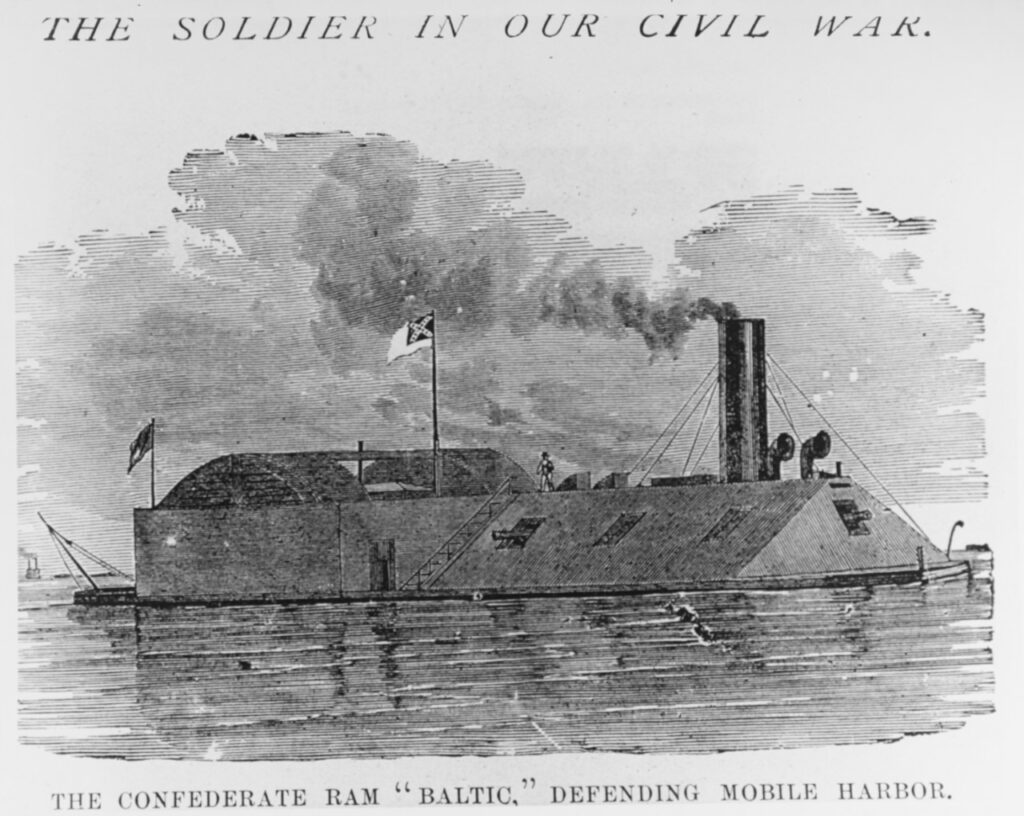

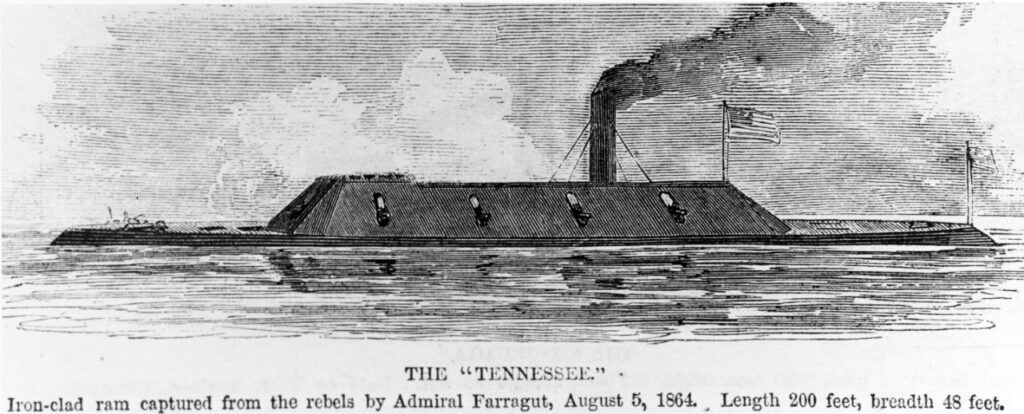

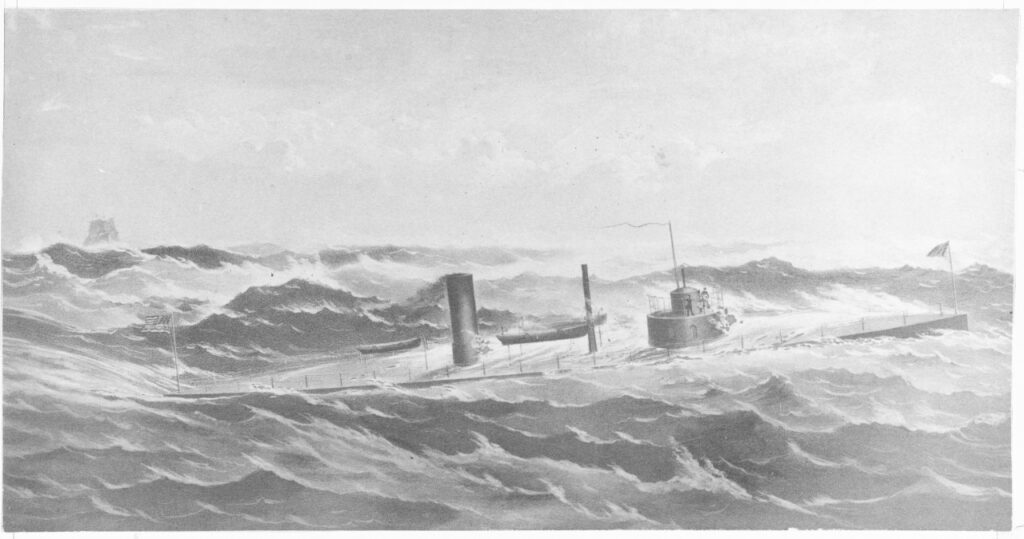

Buchanan pushed forward the construction of four ironclads: the floating batteries CSS Huntsville and CSS Tuscaloosa, as well as the rams CSS Tennessee and CSS Nashville. While it appeared fortunate that the state of Alabama had completed the slow and unmanageable sidewheel ironclad CSS Baltic, Baltic was nothing more than a poorly armored towboat lighter. It was considered ‘rotten as a punk, and … as fit to go into action as a mud scow.’7 Eventually Baltic’s armor was removed to place on CSS Nashville. CSS Tennessee was one of the best Confederate-built ironclads when it was commissioned on February 16, 1864. Armed with two 7-inch Brooke rifles, two 6.4-inch Brooke rifles, and a cast iron ram, Tennessee was heavily armored and could make six knots. Once he had this ship operational, Buchanan wished to wait until Nashville was ready before striking out against Union blockaders. Great things were again expected of Buchanan, and he was under considerable pressure from President Jefferson Davis to act immediately. “Everybody has taken it into their heads that one ship can whip a dozen and if the trial is not made”, Buchanan wrote Flag Officer John K. Mitchell Head, Office of Orders and Details, “we who are in her are damned for life, consequently the trial must be made. So goes the world.”8

Courtesy Naval History and Heritage Command, NH 58793.

Buchanan considered a strike against New Orleans, as suggested by Stephen Mallory; however, he needed Nashville and the cooperation of the Confederate Army to have any chance of success. Nevertheless, Buchanan planned to attack Rear Admiral David Glasgow Farragut’s fleet as it was being assembled out in the Gulf of Mexico. If Tennessee could dispense Farragut’s force before any monitors arrived, then Buchanan could delay any Union advance. On May 22, 1864, Buchanan prepared to attack Farragut at night; yet, bad weather postponed the attack. On the next morning, the attack was foiled when Tennessee ran aground. Buchanan reluctantly called off the attack and decided not to take any offensive action.

FARRAGUT’S ASSAULT

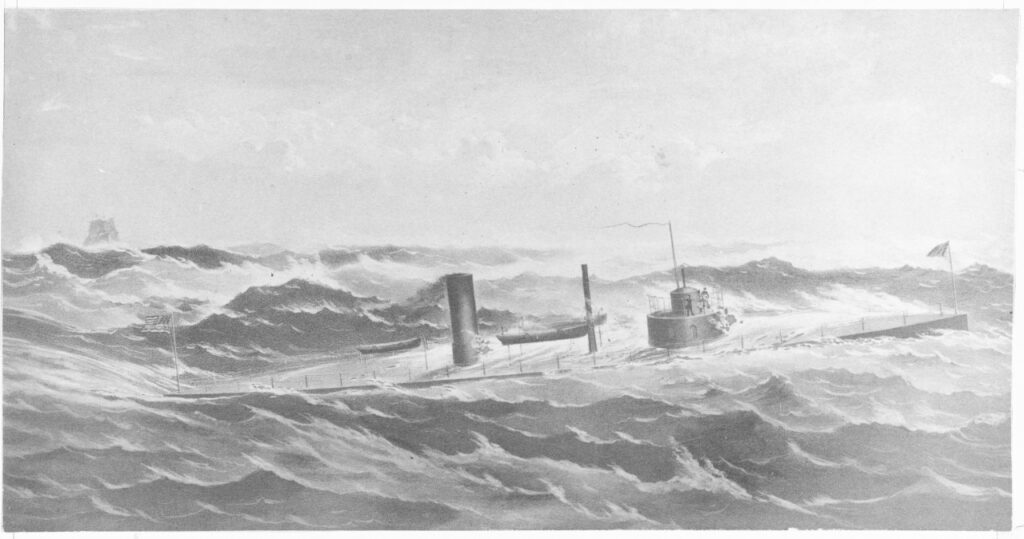

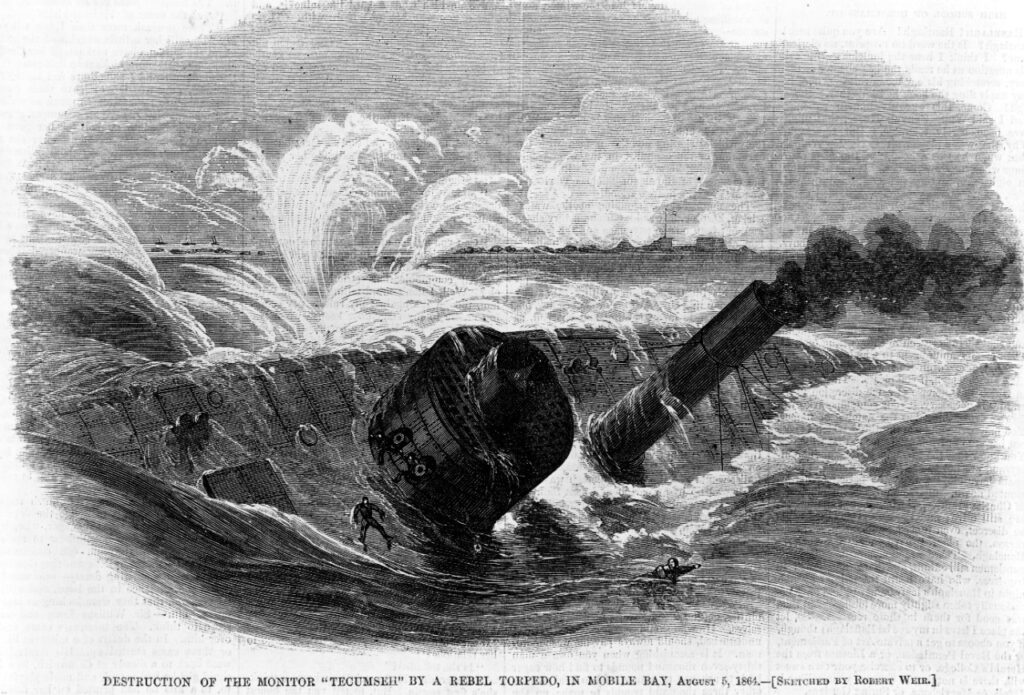

Before CSS Nashville received all its armor, or any other Alabama ironclads were able to support any offensive movement, Farragut started his attack on Mobile Bay. The Union Admiral had been waiting for ironclads to arrive as he firmly believed that ironclads against wooden vessels would make for a most unequal contest. He had already received in the days before both USS Manhattan and the twin-turreted river monitors USS Winnebago and USS Chickasaw. On the evening before the attack, the Canonicus-class monitor USS Tecumseh arrived. Everything was now ready for Farragut’s daring assault past the Confederate defenses guarding the entrance to Mobile Bay.

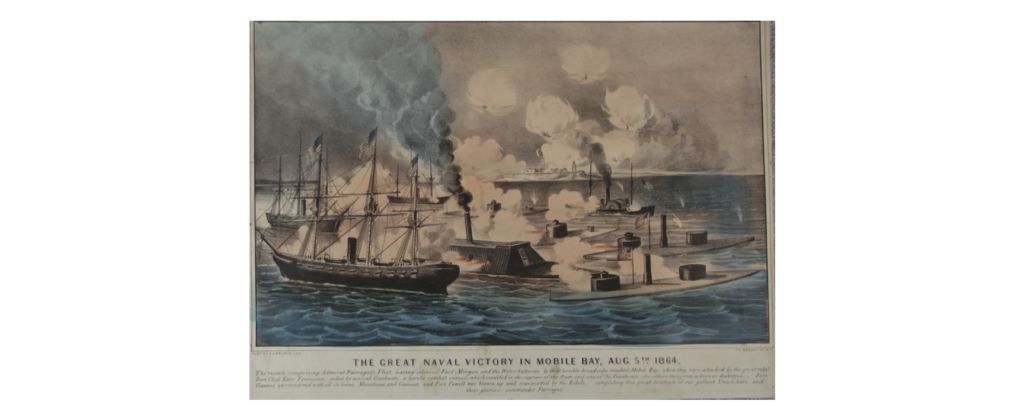

Dawn, August 5, 1864, broke beautiful and cloudless. An early morning floodtide would help the Union warships to pass the forts. The southwest breeze would blow the battle smoke over Fort Morgan, partially blinding the fort’s gunners’ aim. Farragut’s fleet came toward the bay’s narrow channel in two columns: nearest the fort steamed Tecumseh, Manhattan, Winnebago, and the outer column had sloops of war lashed to the smaller gunboats. This column was wasted by USS Brooklyn, as it carried an anti-torpedo raft at its bow.

SINK BEFORE SURRENDER

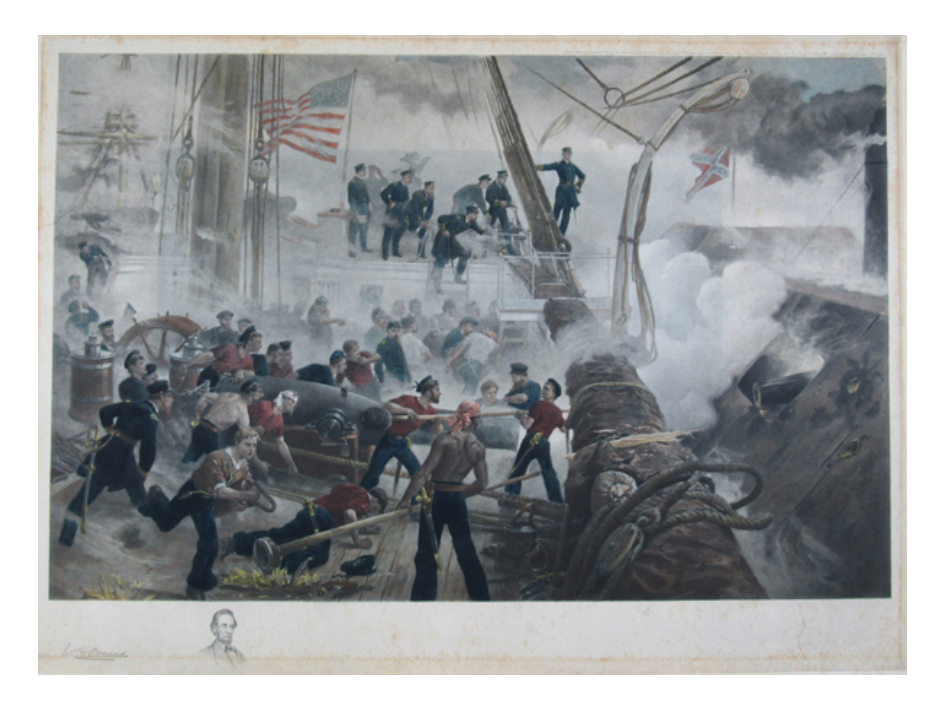

As Fort Morgan began to pound the Union warships, Tennessee was readied for action. Buchanan addresses his crew: “Now men, the enemy is coming and I want you to do your duty; and you shall not have it to say when you leave this vessel that you were not near enough to the enemy, for I will meet them, and then you can fight alongside of their own ships; and if I fall, lay me on one side and go on with the fight. And never mind me – but whip and sink the Yankees, or fight until you sink yourselves, but do not surrender.” 9

Courtesy Naval History and Heritage Command, NH 56271.

LOSS OF USS TECUMSEH

Buchanan wanted to cross the ‘T’ of the enemy’s formation. This would enable his fleet to fire their broadside guns down the Union columns. His major goal was to ram the leading Union sloop of war causing it to sink and block the channel. He saw the column of monitors heading towards his ironclads and wanted to pass them to concentrate on the wooden ships. In turn, USS Tecumseh’s primary purpose was to engage the Confederate ram and either ram it or bash it with its two XV-inch Dahlgrens. Johnston ordered his gunners not to fire until contact; yet, they were amazed by the events that occurred before their eyes. A loud explosion lifted Tecumseh’s bow into the air as the warship turned into its port side. In less than 90 seconds, the stern had risen up into the air, so that you could see the ship’s propellers churning, then quickly dove into the sea. Only 21 of the 113 crew survived. Everyone in both fleets was stunned.

Courtesy Naval History and Heritage Command, NH 61473.

DAMN THE TORPEDOES

The dramatic destruction of USS Tecumseh caused the entire Union column to pause in confusion. USS Brooklyn stopped and began to reverse. The federal fleet seemed stalled and the warships were being pounded by Fort Morgan’s heavy guns. Captain James Alden of USS Brooklyn signaled to Hartford, ‘Torpedoes Ahead.’ Farragut replied with his legendary command, “Damn the Torpedoes! Full speed ahead!” USS Hartford steamed past Brooklyn through the minefield into the bay.

Meanwhile, Buchanan attempted to ram the Hartford and missed as the Union ship was just too fast for the Confederate ironclad. Tennessee circled about and missed the Hartford again as it also missed Brooklyn, Richmond, and Lackawanna. While these ramming attempts were being made, Tennessee and two of its supporting gunboats, CSS Selma and CSS Gaines, shelled the Union fleet as it passed. Both Confederate wooden gunboats were put out of action by Federal shot and shell. Tennessee then anchored near Fort Morgan as Buchanan pondered his next move.

The Mariners’ Museum and Park, 1945.0424.000001.

ATTACK

Buchanan did not wish to scuttle or surrender his ironclad, and then suddenly told Commander James Johnston to move against Farragut’s fleet. One seaman commented, “It looked to me that we were going into the jaws of death.” Dr. Conrad was shocked and asked Buchanan, “Are you going into that fleet Admiral?” Buchanan responded, “I am, sir!” Conrad then mumbled, “We’ll never come out of there whole.” The Admiral overheard the comment and told Dr. Conrad, “That’s my lookout sir.”10

At 9:00 a.m., CSS Tennessee slowly steamed toward the Union anchorage. Farragut was surprised by this Confederate advance and commented, “I did not think Old Buck was such a fool.” Buchanan intended to strike at Farragut’s entire fleet, his six guns against 157 guns. Farragut ordered Monongahela and Lankawanna to “run down that rebel ram.” The sloop of war Monongahela was the first Union warship to close on Tennessee. Johnston saw it coming and ordered the men on the gun deck to “steady yourselves…stand by.” Monongahela struck the ironclad at an angle which knocked down many men inside Tennessee. Johnson was amazed and jubilant: “We are all right … They can never run us down now.”11 USS Lackawanna rammed the Confederate ram next, while Tennessee was heeled over. The Union warship suffered most as its stem was crushed. The ships laid side by side as shot was poured into both of them. Lackawanna’s sailors threw a holystone and spittoon at Tennessee as a Confederate sailor thrust his bayonet into a Yankee blue jacket. The end result of this close fighting was that one of Tennessee’s gunports was rammed by a shot from the Lackawanna.

Farragut then ordered Hartford to ram Tennessee. It was almost a head-on collision and the two ships slid alongside each other firing their cannons as they passed each other. Captain Percival Drayton later claimed that he saw Buchanan working on the gun deck and threw his binoculars at him, shouting, “You infernal traitor!”12 As Hartford turned to ram the rebel ram again, it was accidentally rammed by Lackawanna which cracked Hartford down to the waterline.

Now it was the turn of the monitors to attack the Confederate ironclad. USS Manhattan approached with its two XV-inch shell guns. Lt. Arthur D. Wharton remembered, “When a hideous monster came creeping up on our port side, whose revolving turret revealed the cavernous depths of a mammoth gun. … Stand clear of the port side! I shouted. A moment after, a thundering report shook us all, while a blast of dense sulfurous smoke covered our portholes, and 440 pounds of iron, compelled by 60 pounds of power, admitted daylight through one side, where before it struck us, there had been over two feet of solid wood, covered with five inches of solid iron.” That shot, from Manhattan’s 15-inch gun, was the only one during the battle to penetrate Tennessee’s armor.13 The netting installed by Buchanan limited the impact of splinters on the crew.

BUCHANAN WOUNDED AGAIN

Now another ironclad, CSS Chickasaw, positioned itself near Tennessee. Chickasaw pumped 52 shells into the Confederate ironclad from a range of 12 to 50 feet in less than an hour. Buchanan endeavored to repair the jammed gunport. Two mechanics, with their backs to the casemate wall, held a metal bolt as two more crew members struck at the shutter using sledgehammers. The Admiral was personally supervising this work when a shot from Chickasaw hit the casemate where they were working. Both mechanics were split in two, while Buchanan suffered a compound fracture to his left leg. It was bent out in a strange angle. Dr. Conrad asked, “Admiral, are you badly hurt?” Buchanan simply replied, “I don’t know.”14

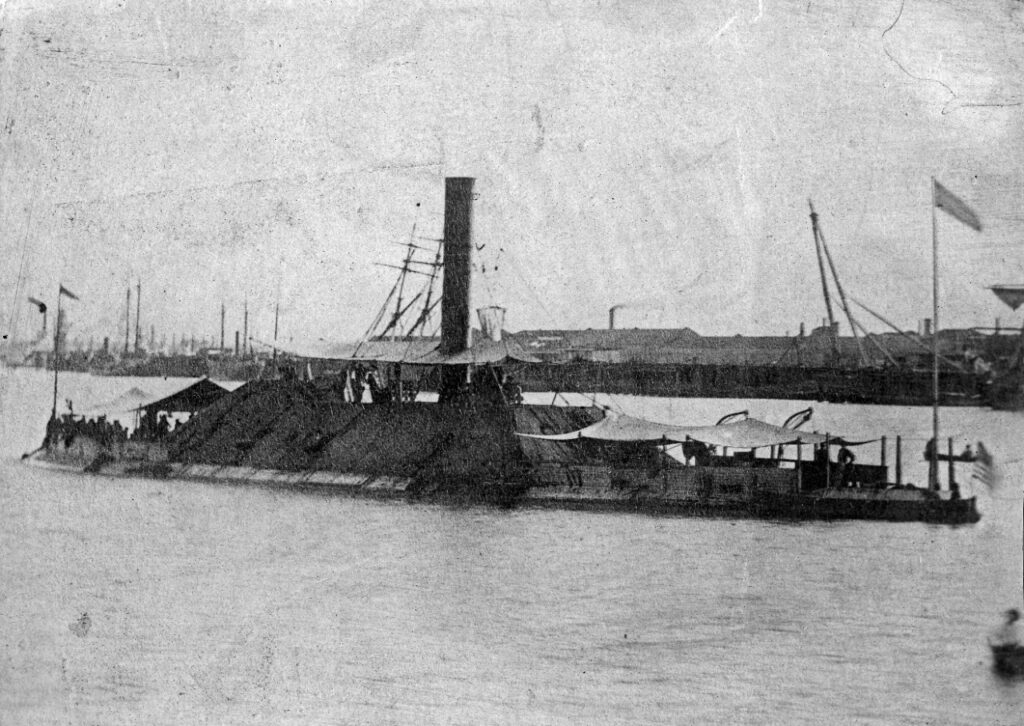

The Mariners’ Museum and Park, 1939.0325.000001.

A FLOATING WRECK

Conrad knew that he could not treat the Admiral on the gun deck, so he then carried Buchanan on his back “down the ladder to the cockpit, his broken leg slapping against me as I moved slowly along.” 15 Commander Johnston came to see Buchanan. The badly injured flag officer stoically told the ship’s captain, “Well, Johnston, they have got me again. You’ll have to look out for her now; it is your fight.” Johnston replied,” All right. I’ll do the best I know how.”16

Courtesy Naval History and Heritage Command, NH 60335.

By now, Tennessee was a floating wreck — simply helpless in the water. The ironclad was dead in the water with its steering chains broken. The smoke stack had been shot off so that the engines had no draft and the gun deck filled with suffocating fumes and heat. Tennessee, furthermore, was unable to defend itself: primers were faulty and most of the guns unable to fire because of jammed port covers.

Johnston went back down to report this all to Buchanan, who retorted, “Do the best you can, sir. And when all is done surrender.” Tennessee’s commander then returned to the gundeck and seeing that “the ship was nothing more than a target for the heavy guns of the enemy” he knew that there was nothing more to be done than surrender.17

Courtesy Library of Congress, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cwpb.04943.

Battle of Mobile Bay was the last major naval engagement of the Civil War, as well as being the last battle in which “Old Buck” would fight. His first Civil War encounter, the sinking of USS Congress and USS Cumberland was an impressive victory and earned him the rank of Admiral; it also resulted in a painful wound to his right leg. Buchanan was still on crutches when he received his new assignment as commander of the Mobile Bay Squadron. The energy he retained from his Battle of Hampton Roads was tested as the Admiral developed ironclads and prepared to defend Mobile Bay. Like March 8, 1862, Buchanan only had one ironclad to counter the entire Union fleet. Yet, his ironclad was too slow to ram Farragut’s wooden and iron vessels and by mid-morning August 5, 1864 CSS Tennessee was dead in the water and Buchanan badly wounded. Mobile Bay was his last battle and was the only time he had ever surrendered his sword.

THE ADMIRAL’S LAST YEARS

Buchanan would be taken to Pensacola Naval Hospital to treat his gruesome wound. At one point, the doctors were concerned that the Admiral’s leg might need to be amputated. When the surgeons asked him what should they do, Buchanan replied, “You captured it, you decide!” His leg was not removed. Once Buchanan healed, he was imprisoned at Fort Lafayette, New York, until exchanged in February 1865. He was reassigned to Mobile, but the city surrendered and the Confederacy collapsed before he could return to duty.

After the war, Buchanan retired to Talbot County, Maryland. He was appointed president of the new Maryland Agricultural College (later University of Maryland); however, he resigned after two years of service over complaints from the faculty and students that he endeavored to operate the college like a ship. Then he moved to Mobile, Alabama, as secretary of the Alabama Life Association. He died on 11 April 1874, at his estate, “The Rest,” near Easton, Maryland.

Endnotes

- Eggleston, John R. “Captain Eggleston’s Narrative of the Battle of the Merrimac,” Southern Historical Society Papers 40 (1916), 168.

- Ramsay, Henry Ashton, “The Most Famous of Sea Duels, The Story of the Merrimac’s Engagement with the Monitor, and the Events that Preceded and Followed the Fight, Told by a Survivor.” Harper’s Weekly, February 10, 1912, 11.

- Lewis, Charles Lee. Admiral Franklin Buchanan. Baltimore, MD: Norman Remington Company, 1929, 166.

- Ibid., 163; Dudley, William S. Going South: U.S. Navy Officer Resignations & Dismissals on the Eve of the Civil War. Washington, D.C.: Naval Historical Foundation, 1981, 8.

- Welles, Gideon. Diary of Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy under Lincoln and Johnson. Edited by Howard K. Beale. 3 vols. New York: W.W. Norton Company, 1960. 1:19; Swartz, Oretha. “Franklin Buchanan: A Study in Divided Loyalties.” United States Naval Institute Proceedings 88 (December 1961): 62-66.

- Still,William N., Jr. Iron Afloat: The Story of the Confederate Armorclads. Columbia, SC:University of South Carolina Press, 1985, 190

- Ibid, 80

- Still, The Confederate Navy, 203

- James D. Johnston, ‘The Ram Tennessee at Mobile Bay, Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. New York: Century Magazine, Vol. 4:402 and Conrad, “Capture of the C.S. Ram Tennessee in Mobile Bay, August, 1864,” Southern Historical Society Papers 19 (1891): 72-73

- Conrad, 74

- Conrad, 75-76

- Conrad, 77, Hearn,Chester. Mobile Bay and the Mobile Campaign: The Last Great Battles of the Civil War. Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland, 1993. 103-105 Drayton to Farragut, 5 August 1864, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1906, Series 1, Vol.21: 466

- Nashville Daily American, September 13, 1877

- Conrad, Capture of the Ram Tennessee, 77

- Ibid, 77-78

- Conrad, 77-78

- ORN, Vol 21, 580