Over the past few months, Drootin Woodhull1 (our VP of collections and chief curator) has been working on crafting a presentation on the Liverpool school of painting for a Lifelong Learning session. While looking for an image of the Bidston Hill lighthouse and signal station to illustrate the communication system between Holyhead and Liverpool, he ran across an interesting blog post by Andrew Williams at the Victoria Gallery and Museum. Mr. Williams’s post discussed how the named signals on a circa 1793 creamware mug depicting the Bidston Hill signal station revealed Liverpool’s extensive participation in the transatlantic slave trade.

Our Collection holds three pieces of creamware with the same decoration whose catalog records contained little information, so I viewed Mr. Williams’s post as an excellent launching point for a small recataloging project. Following his lead, I began researching the history of Bidston Hill and the names associated with the flags. To my surprise, one of the names, William Orange, a merchant who operated a packet service between Liverpool and Dublin, had lived in Norfolk, Virginia between 1742 and 1771!

Bidston Hill Lighthouse and Signal Station

King John granted Liverpool a Royal Charter in 1207 because he needed a port from which he could quickly dispatch men and supplies to Ireland. Liverpool was still relatively small at the start of the 17th century (its population was barely 2,000 people) but its reputation as a good trading port had already started to develop. When England’s North American and West Indian colonies began to expand in the late 17th century, a corresponding expansion occurred in Liverpool, which was strategically located to exploit trade with the colonies. By the mid-18th century, Liverpool had become the third-largest port in England.

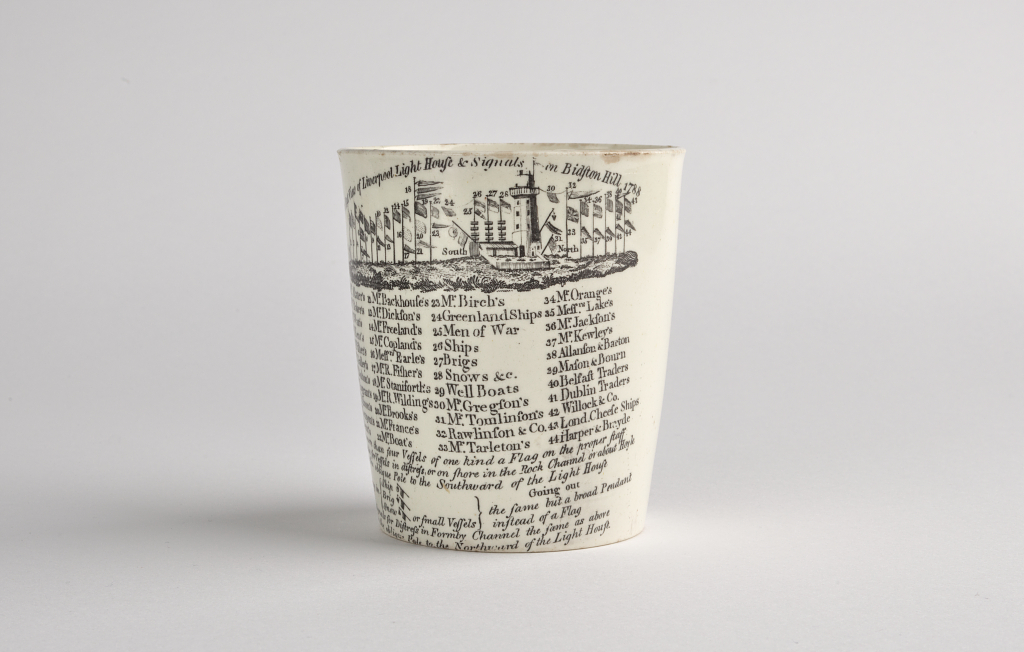

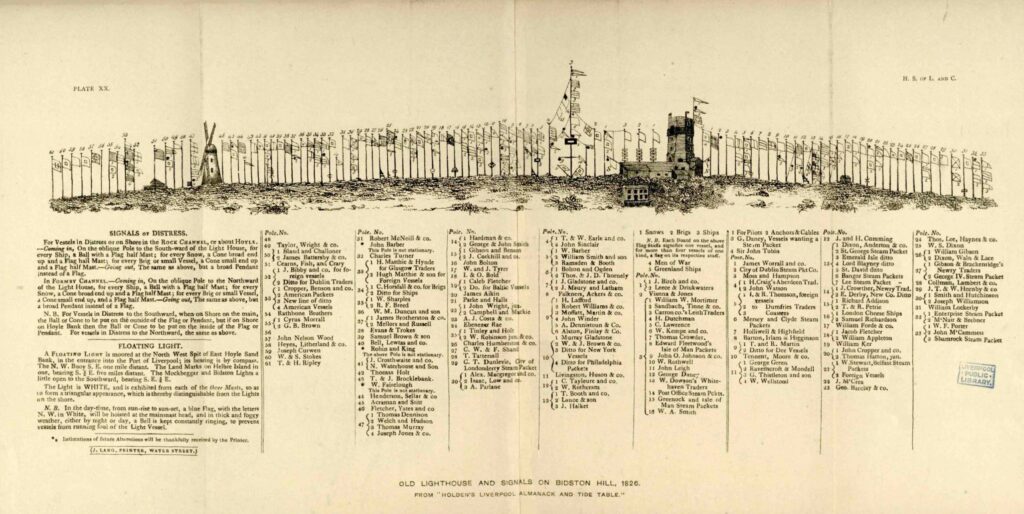

In 1763, a signal station was built on Bidston Hill at the entrance of the Mersey River. It was meant to serve as an early warning system of the impending arrival of merchant ships in Liverpool. Merchants would arrange with the signal station keeper to place a flagpole in an agreed position and would supply the keeper with a flag unique to that particular merchant. Ships entering the Mersey River would hoist their owner’s signal and runners stationed on Bidston Hill would hoist the same flag on the appropriate pole. When dock workers in Liverpool spotted the merchant’s flag flying on Bidston Hill, they would begin preparing for the arrival of the merchant’s vessel. Reflecting the importance of Bidston Hill’s position to the waterways leading into Liverpool in 1771, the town’s dockmaster, William Hutchinson, built a lighthouse at the station to aid navigation in the Mersey. Since the approaches to the port were navigationally tricky, the keeper at Bidston Hill also established a system of “immediate signals [that could be made] to the town of all vessels seen in distress in either of the channels, that thereby speedy assistance may be given.”2 Signals were also established for generic vessels like men of war, ships, brigs, Belfast or Dublin traders, and the London Cheese Ships3 just to name a few.

The size of the station grew in proportion to the expansion of commerce in Liverpool. In 1778, there were 14 flagpoles. In 1793, there were 56 numbered flags — including one for “enemies” in case French ships were spotted in the Irish Sea. By 1820, there were 195 named signal flags. Amazingly, the signal station remained in operation until 1913.

According to Williams, the signal station was “a very popular symbol of Liverpool in the late Georgian and early Victorian period.” Images of the station with a key for the flags were printed on paper for sightseers, included in publications, and placed on ceramics and depicted in other artworks. Bidston Hill even appears on a needlework sampler in the collection of the Cooper Hewitt Museum in New York.

The first creamware objects decorated with an image of Bidston Hill appeared in 1788. The first edition of the image includes 44 named signals. Unfortunately, our objects, like many others, have not been marked by the manufacturer. Researcher Charles T. Gatty, who studied Liverpool pottery manufacturers, theorized that the printed creamware pieces showing Bidston Hill had been produced by Guy Green. With his partner John Sadler, Green had developed a thriving business producing transfer printed creamware in the 1760s. They were the first company in Liverpool to produce such wares. Josiah Wedgwood had produced most of the wares decorated by Green and Sadler. Green maintained a relationship with Wedgwood after Sadler retired in 1770, suggesting a possible maker for our 1788 beaker and jug, but I digress!

William Orange’s Liverpool Business

As I mentioned earlier, our Collection holds three pieces of creamware with the Bidston Hill image: a small jug and a beaker showing 44 named flags, both dated 1788; a slightly larger jug dating between 1790 and 1792 showing 52 named flags; and one instance of a merchant with a flag but no pole of his own. To research the names on the beaker and jugs I started with the two resources Andrew Williams suggested: the Liverpool Registry of Merchant Ships and the Trans-Atlantic Slave Voyages Database. I then moved on to other publications, newspapers, and websites until I had enough information to compile short biographies of each man’s business. As I systematically moved through the list of names on each jug, I discovered that two names on the 1788 beaker and jug did not appear on the jug from two years later: Mr. Galley and Mr. Orange. As it turned out, both of these men had died in 1789. William Orange died on January 23, 1789, and John Galley died in April 1789.

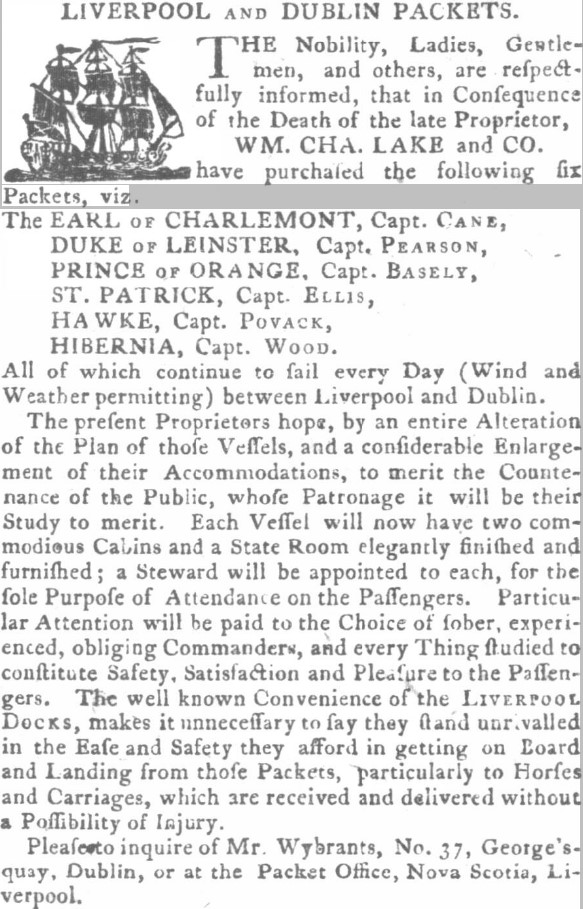

John Galley was a slave trader. He was part owner of 15 vessels, at least 13 of which conducted 25 slaving voyages between 1770 and his death in 1789. The Slave Voyages database revealed that for a short time, William Orange was also a shareholder in slaving vessels. Between 1772 and 1774, Orange was part owner of three ships that conducted four slaving voyages.4 He left the slaving business fairly quickly, leaving one to wonder if he did it to gain the capital to jumpstart his business in Liverpool because by 1773 or 1774, Orange had acquired, probably with a partner, a small 70-ton brig called Fly, which he used to establish a packet service between Liverpool and Dublin. Over the next fifteen years, Orange accumulated a small fleet of six ships, usually partnered with a widow named Fanny Kelley. He was the sole owner of the last vessel he acquired, an 80-ton brig named St. Patrick that had been built in Dublin in 1787, possibly right before his death. In fact, he may have never seen that vessel enter service.

Starting in February 1781, the 60-year-old Orange began suffering from some sort of severe illness. His surgeon, Joseph Goldie, stated that he “from being a stout and healthy man, began to complain of Rheumatick pains, want of appetite, and [was] unable to take his usual exercise. In March, he grew worse…[and] there was great cause to think he could not outlive the winter.”5 Despite his illness, Orange’s business prospered, and his little fleet maintained an active service with vessels sailing almost daily from each port.

William Orange died on January 23, 1789, and was buried at St. James in the District of Toxteth, Liverpool. His stake in the six packet ships was acquired by another prominent Liverpool merchant, who also happened to be his son-in-law, William Charles Lake and Company. The executors of his estate (along with Lake) were other Liverpool merchants: John Sparling, William Bolden, and Richard Hunt, who had also lived in Norfolk for many years.

William Orange’s Local History Revealed

While researching the named signals, I discovered that conducting a generic internet search was always a good idea since many of the merchants engaged in the slave trade had been researched and discussed online. In the case of Orange, it wasn’t a website I found but a 1991 Ph.D. dissertation by Thomas Costa titled Economic Development and Political Authority: Norfolk, Virginia merchant-magistrates, 1736-1800. As I read it, my mind was blown — William Orange, the guy whose signal flag was depicted on our Liverpool creamwares — had lived in Norfolk, Virginia for nearly 30 years!

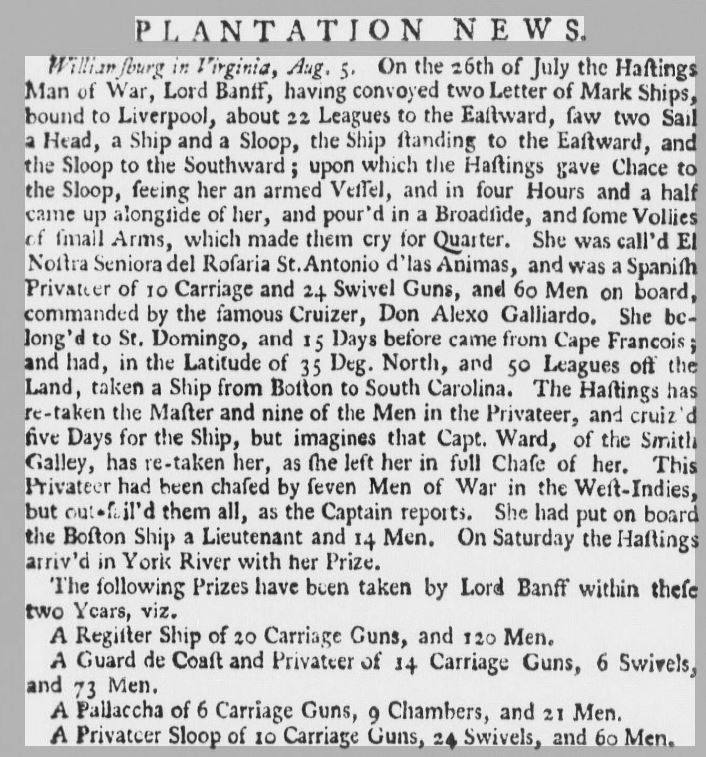

Orange “being bred to the sea, enter’d into the service of his King and Country in the year 1740”6 (i.e. he joined the Royal Navy). While I don’t know the details of Orange’s Royal Navy service, there is some evidence of the end of his naval career, which provides an interesting theory. The September-October 1744 muster of the ship HMS Hastings indicates that William Orange had been released from service while the ship was in Virginia. For four years starting in 1741, Hastings, a 40-gun fifth-rate ship captained by Alexander Ogilvy (Lord Banff), was stationed in the West Indies and Virginia and spent a great deal of time in the Norfolk, Hampton Roads, and York River regions. The ship was lucky under Banff and captured several valuable prizes. Banff himself was said to have earned some £20,000 from the captures. If, as I suspect, Orange was stationed on Hastings, it’s possible that on his release from the Navy, Orange also had a pocket full of prize money from which he was able to establish himself in business.

In later documents, Orange stated that he settled in Norfolk in 1742 or 1743. Reputedly, he married a woman named Mary Malbone (or Milbourne) Kenner (or Kenna) in 1743, but records supporting the marriage have not been found and may not survive.

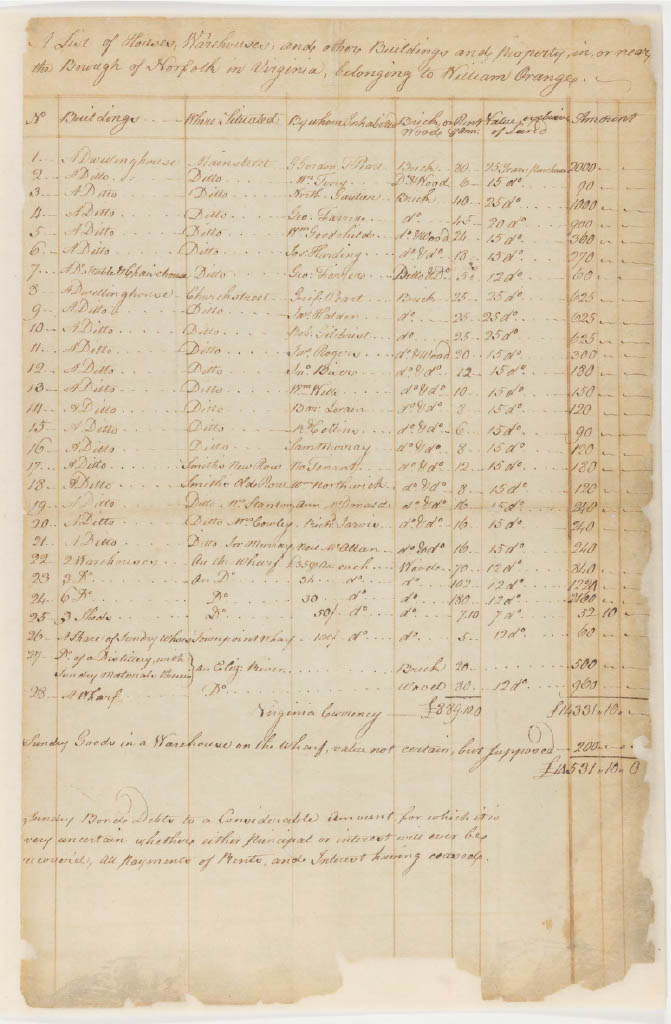

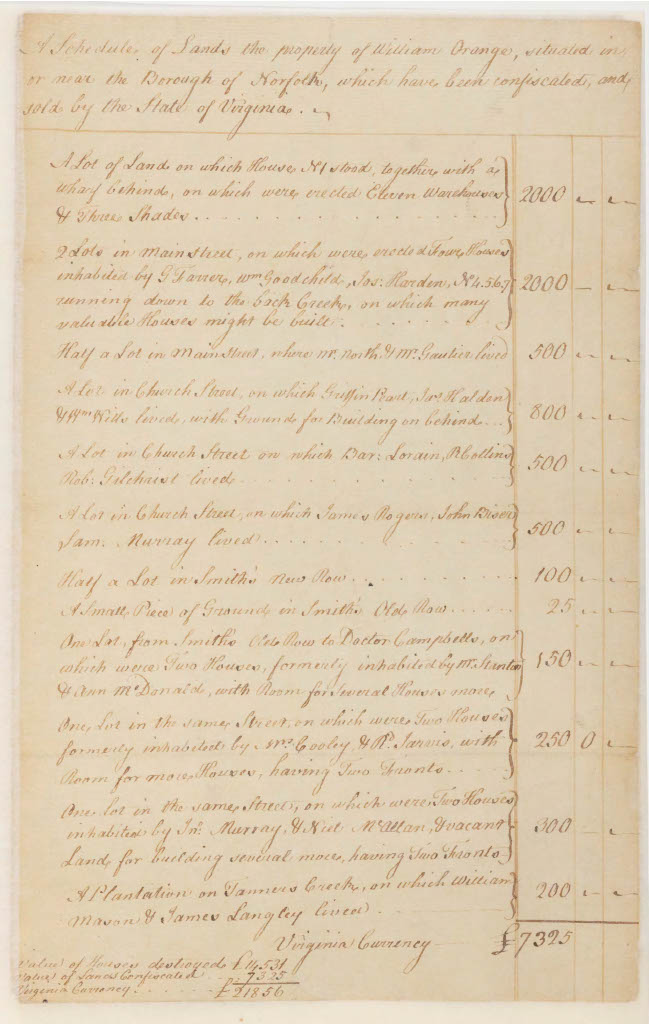

Orange established what would eventually become a successful business by partnering with other Norfolk merchants in the West Indies-England-Virginia trade, bringing in goods for sale to the public and for personal consumption. As his business developed, Orange began acquiring properties in and around Norfolk. By the time he left Virginia in 1771, Orange owned nearly 40 buildings (houses, warehouses, and sheds); a large wharf that Dr. Alexander Gordon (Orange’s lawyer) described on February 12, 1785, as “one of the greatest works of the kind that ever had been erected in that country”; a 170-acre plantation on Tanner’s Creek (now the Lafayette River); and shares in the wharf and warehouses at Town Point and a large distillery. The annual rents on all these properties brought Orange around £900 a year in income.

Thanks to his successful business and growing affluence, Orange was elected a Norfolk borough common councilman on June 25, 1750. During his tenure, he assisted with the oversight of the construction of the borough prison (1753), and in 1763, he worked on a committee to determine how many watchmen and lamps were needed in the borough.

Orange’s position within the town’s leadership also opened up other money-making opportunities. Between 1755 and 1767, he took on the job of keeping the “publick pumps in good repair.” In consideration for this service, the council gave Orange £5 and he was entitled to the “profits arising by the ships &c [etc.] watering at the said pumps.”7 Eventually, the number of pumps became too great for one man to handle, and other council members took on pumps until Orange’s task was limited to the pump at Cambridge Alley. In 1766, his responsibility shifted to the pump on the “school land.”

In 1760 and 1761, Orange was on the committee that drafted the “Act for Enlarging and Ascertaining the Limits of the Borough of Norfolk…” which was enacted on April 10, 1761. Besides expanding the size of the borough to include nearby tracts of developed land, the act proposed the stabilization of the land at Town Point and the building of a new wharf with warehouses. Several gentlemen in the government and town acquired shares in the wharf, and in consideration, they received a yearly dividend whose size was based upon the profits of the wharf and the initial investment amount. Orange invested £50.

During his residence in Norfolk, Orange joined the Norfolk Borough Battalion, a militia unit. He rose to the position of lieutenant on November 21, 1755, became a captain on April 16, 1761, and a major, a title he retained when he returned to England, on February 17, 1764. By 1761, Orange was a vestryman in the Elizabeth River Parish (St. Paul’s Church in Norfolk was the parish church), and by 1765, he was a churchwarden.

Prelude to Orange’s Departure from Norfolk

According to Thomas Costa’s dissertation, one of the unique features of Norfolk was the “closed, corporate nature of the town’s leadership.” The town’s mayor and eight aldermen served for life and also “comprised the magistracy of the borough, exercising executive and judicial authority within the town.”8 By the 1760s, the incestuous nature of the town’s leadership, which excluded newer arrivals in the colony and businessmen with no familial connection to Norfolk’s original founders, was causing a rift between Norfolk’s commercial and political elite.

The increasing tension between the two groups periodically erupted into violence in the 1760s. During these episodes, the behavior of the Norfolk magistrates, who despite being in leadership roles were many times found to be encouraging, supporting, or even leading the violent acts, began to erode faith in the ability, or even will, of the magistrates to maintain order in the town.

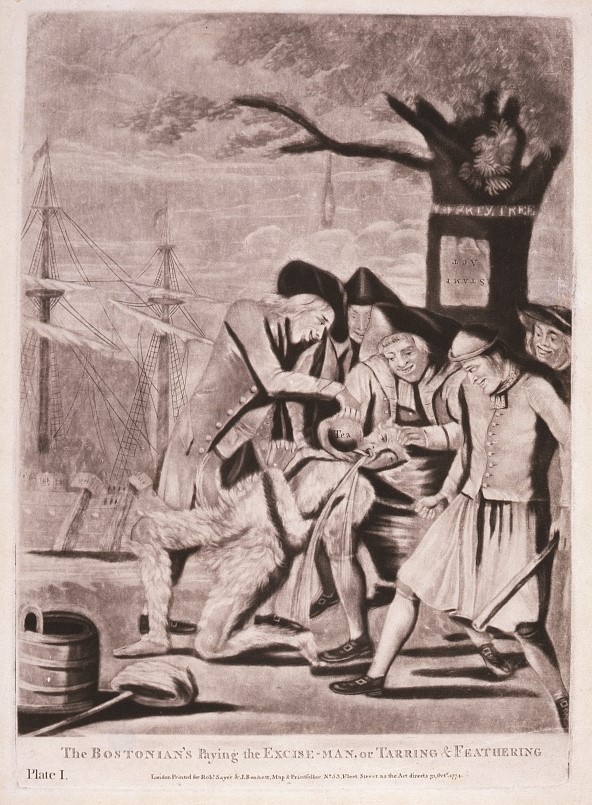

In one example, in March 1766, a Norfolk chapter of the Sons of Liberty was established and led by Alderman Paul Loyall to protest the Stamp Act instituted by Parliament on March 22, 1765. According to Costa, unlike other chapters of the Sons of Liberty, the Norfolk chapter had a higher proportion of community leadership because its members were primarily merchants in the town. Shortly after the group’s founding, a mob made up of members of the Sons of Liberty and encouraged by Norfolk’s mayor, Maximilian Calvert, stoned, tarred and feathered, and nearly drowned Captain William Smith (master of the schooner Gilchrest), who they accused of informing British officials of customs violations related to the Stamp Act.

As a major in the Norfolk Borough militia, Orange took a stand against the Sons of Liberty in an effort to maintain order. The response to his position must have been serious because, in his 1785 memorial to the British commissioners overseeing the distribution of relief to loyalists, Orange stated that “by taking an active part in support of [the] Gov[ernmen]t ag[ain]st the opposers of the Stamp Act he became the object of Resentm[en]t to an infatuated mob who treated him with such wanton cruelty that his life was long despaired of.” This statement was backed up by a May 20, 1766 letter from Lt. Governor Francis Fauquier in which he states that Orange “has been grossly insulted and abused for standing in support of that Government which protects him.” In the same letter, Fauquier chose Orange’s candidate for vendue master (public auctioneer) over a candidate with close ties to the Sons of Liberty, further raising the ire of the group. The situation must have been difficult because the following year, Orange felt the need to resign his seat on the common council.

The problems with violence in Norfolk continued. In 1768, a conflict broke out among Norfolk’s citizens regarding the process of inoculation against smallpox. Despite many people’s stance against inoculation, which they felt would inflict an epidemic on the town, a small group of men wished to have their families inoculated against the disease. The differing opinions about the process and anger that developed when the group moved forward with the process caused a number of riots and violent acts against the “inoculationists” (supporters of inoculation).9 As a supporter of inoculation, Orange was terrorized by a mob.

By late 1769 or 1770, Orange appears to have had enough of the violence and rotten politics in Norfolk and decided to return to England. He sent his family to Liverpool in 1770, while he began the task of shutting his business down. He began advertising his departure to clear any debts due or owed and to arrange long-term leases on his properties. Orange traveled back to Liverpool in late 1770 or early 1771 and disappeared from the list of tithable persons in Norfolk in June. Advertisements posted by George Gordon (possibly his agent) in late 1771, and again in 1773, seem to indicate that after Orange’s return to England, he was still having trouble getting money from his debtors.

Orange does not appear to have foreseen what the increasing opposition to British policies and problems in Norfolk was leading to as he continued to conduct his business from Liverpool. While I was unable to find any significant details of the operation, Orange was apparently in partnership with a man named Hargraves up until 1774. He also retained ownership of his properties and placed them under the management of an agent so he could continue to accumulate the rental income. Orange even continued to acquire property, purchasing a half lot with two wood houses in Smith’s New Row in 1775.

If you know the history of Norfolk in the Revolutionary War, you’ll know that the business William Orange had built over the previous 34 years came to a crashing halt in January of 1776. During that month, Norfolk became the only town in Britain’s American colonies to be wiped off the map. Interestingly, it wasn’t the British committing the greatest acts of destruction in Norfolk. Troops organized by the provisional governments of Virginia and North Carolina had been ordered to destroy the town to prevent the British from using Norfolk as a base of military operations from which they could control Virginia and the entire Chesapeake Bay region. In fact, some feel that the destruction of Norfolk in 1776 “proved a crucial decision with far-reaching strategic and military consequences that sowed the seeds of the British defeat at Yorktown in October 1781.”10

The destruction started on the afternoon of January 1st, 1776 when Lord Dunmore’s ships anchored in the Elizabeth River began bombarding the town. Troops were sent ashore to raid warehouses and burn buildings near the waterfront, but the British effort proved fairly ineffective with only 19 houses/buildings destroyed. The response of patriot troops over the next two months destroyed 1,279 buildings — 96 percent of the town. Orange’s losses accounted for forty buildings and property valued over £14,000 (exclusive of the land). In later memorials, this value was raised to somewhere between £22,000 and £30,000.

The final destruction of Orange’s Norfolk business occurred on May 29, 1779, when the Virginia General Assembly passed “An Act Concerning Escheats and Forfeitures from British Subjects,” which ordered the seizure and sale at public auction property owned by loyalists. Initially, the jury overseeing the Confiscation Act would not bring a verdict against Orange because he had left Norfolk well before the Revolution. They eventually got around this impediment by having two men swear that Orange was known to have fitted out privateers to sail against the Americans — a falsehood perpetrated by Norfolk borough leaders in an effort to acquire Orange’s land. On August 8, 1779, just three pieces of his sequestered property were sold for £98,200.

While Orange did receive annuity payments from the British government starting in April 1777 (£100) and elevated in April 1778 to £150. He was forced to continually petition the British government to maintain the relief. In early 1781, the king commanded Lord Dunmore (the last Royal Governor of Virginia before the war started) and the loyalists receiving relief to return to Virginia or else relinquish the allowance being paid. To fit himself and his family out for the voyage, he would be given his allowance through July 5th and a year’s allowance in advance from that day and free passage to Virginia. If the war was not over by July 5th, 1782, then some other provision would be made for the people who went with Dunmore to Virginia. Fortunately for Orange, his poor state of health made it impossible. The result was that Orange repeatedly found himself begging the government for the continuation of his relief payments.

In November 1784, he petitioned the Virginia General Assembly “to grant him relief, that they will at least, extend to him the Benefit of the Treaty of Peace, And that your Honors will give him such compensation as your Honors will give him such compensation as your Honors shall think the Hardships of his Case, or the Stipulations of the Treaty aforesaid entitle him to.” What Orange is requesting in this statement is that the provisions of Article V of the 1783 Treaty of Paris be extended to him — unfortunately, in the act, Congress only promised to encourage state legislatures to protect the property rights of loyalists but does not guarantee those rights as the state legislatures could do as they pleased. Orange laid out a claim for reimbursement backed up by testimony from witnesses in early 1785, but it looks as though he never recovered the full value of his property loss or the debts owed to him by Virginia residents.

I find several aspects of this story intriguing. First, King George III ordered Lord Dunmore and the loyalists to return to Virginia in 1781? Really? Did he hope to land a bunch of businessmen and farmers at Yorktown in October with the rest of the British troops? I looked into it and found several reports from April and May of 1781 that indicated it wasn’t the King’s idea. Lord Dunmore had applied to the British government for permission to return to Virginia believing that “his presence in the province…might be beneficial to his country” and that he would be able to form several corps of men and “arm them in assisting towards the reduction of the rebellion in that part of America.”11 Obviously, Dunmore was a complete narcissist with an incorrect and inflated opinion of how Virginians felt about him. Newspapers of the time expressed doubt about the enterprise from the very start and one even blamed the defeat of the British at Yorktown on Virginian’s learning that Lord Dunmore was coming back to govern them. The newspaper stated:

“The measure which injured the King’s affairs most in Virginia, was the news arriving there that Lord Dunmore was to be their Governor again.–This circumstance operated like a charm–it arrested the activity of every man inclined to loyalty, and quickened with exasperated force, the enmity of the rebels. Whoever advised such an impolitic measure, as reappointing the old Governors so detested by the people when the war broke out, should be marked for ever as an enemy to his Majesty and his Councils!”12

Dunmore’s delusion was further illustrated by a report in the Leeds Intelligencer on June 11, 1782, that a reward of $5,000 had been offered by Virginians for “apprehending…the Earl of Dunmore, alive or dead.”

What isn’t in doubt is that it was England’s Prime Minister, Lord North, who required Lord Dunmore to take all the loyalists receiving government support with him to Virginia (I guess he hoped to rid the government of the expense). Thankfully Orange’s “illness,” which reputedly started in February 1781, most certainly saved him from participating in an act that would have economically ruined him. Surely it was obvious to Orange, who had lived in Virginia under Dunmore’s rule and knew how other colonists felt about him, that returning to Virginia was futile. Especially since, for Orange, there was nothing to return to. Maybe the stress of knowing he might be forced to return to Virginia, a virtual economic wasteland for those men branded as loyalists, or lose his governmental support caused the illness?

My second thought is that while Orange certainly appears to have lost his income and properties in Virginia, I’m not wholly convinced he was completely destitute. After all, his packet business between Liverpool and Dublin was up and running before 1776 — granted it doesn’t appear to have been a large business, and he does say he had to borrow money to expand it. Looking at his will, he may have thought that by continuing to petition the British and Virginia governments for support, he might eventually recover his extensive losses (his will references “sum and sums of money or other recompense or gratuity…may everafter receive or be entitled to from Government in consideration of my losses in North America”).

Finally, I was really surprised to learn of the close economic ties between Liverpool and the Chesapeake Bay region and how many Liverpool merchants had lived in Norfolk at some point in their lives. As I already mentioned, one of the reasons for Liverpool’s growth in the 17th century was its strategic location and the development of trade with England’s colonies in North America. Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, a strong triangular trade developed between Liverpool, the West Indies or Africa, and the east coast of North America. A particularly strong trade developed with Norfolk, Virginia, which — by the time of the Revolutionary War — had developed as an active American trading port that eclipsed all but the large northern seaports of Boston, Philadelphia, and New York.13

William Orange was just one of several merchants living in Norfolk with close economic ties to Liverpool. If he hadn’t returned to Liverpool and begun his packet trade, which prompted him to put a flag at Bidston Hill in 1788, I might never have discovered this interesting story!

Endnotes

1. Actually, our VP of collections and chief curator is Lyles Forbes, but for those of you who know him well, you’re aware of his love of improbable or hysterical names. His first name suggestion was Garstang Grappy!

2. A General and Descriptive History of the Ancient and Present State, of the Town of Liverpool…. By James Wallace, published by R. Phillips, Castle Street, Liverpool, 1795, page 17.

3. A thriving trade existed between London and Liverpool in which ships from London came to collect the famous Cheshire cheese that was exported through Liverpool.

4. Ship Juba (ship built in 1771 in Liverpool, 200 tons; shareholders: William Bolden, John Sparling, William Shepherd, Thomas Langton, John Birley, Edward Mason, Cornelius Bourne, William Orange, James Greenhow). First voyage began July 14, 1771. Embarked 282 slaves at Calabar and landed 230 slaves at Barbados. Returned to Liverpool December 18, 1772. Second voyage began March 3, 1773. Embarked 318 slaves at Calabar and landed 260 at Jamaica. Returned to Liverpool December 30, 1774.

5. Letter written by Joseph Goldie, November 9, 1782, Public Records Office, A.O.13/32

6. According to Orange’s November 13, 1784 petition to the General Assembly of Virginia.

7. From The Order Book and Related Papers of the Borough of Norfolk, Virginia 1736-1798, edited by Brent Tarter, published by the Virginia State Library, Richmond, 1979.

8. Costa, page 3.

9. If you want to learn more, read the article Smallpox and Patriotism, the Norfolk Riots, 1768-1769 by Patrick Henderson, published in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Oct., 1965, Vol. 73, No. 4, pp. 413-424.

10. Website of the Journal of the American Revolution, “Norfolk, Virginia Sacked by North Carolina and Virginia Troops” by Patrick H. Hannum. https://allthingsliberty.com/2017/11/norfolk-virginia-sacked-north-carolina-virginia-troops/

11. Caledonian Mercury, April 21, 1781, Reading Mercury, April 23, 1781 and Leicester Journal, May 26, 1781; There is some confusion with this as an April 25, 1781 letter from William Orange to Lord Dunmore states “you had receiv’d his Majesty’s commands to return to Virginia.”

12. Kentish Gazette, January 5, 1782

13. Thomas Costa, Economic Development and Political Authority: Norfolk, Virginia merchant-magistrates, 1736-1800, 1991, page 3.