What’s an attribution, you ask? It’s the act of ascribing an artwork to a particular artist (if the painting isn’t signed) or as a depiction of a particular event (if it isn’t specifically identified by the artist). To attribute a painting to an artist one must be very knowledgeable about the artist’s oeuvre. To make an attribution to an event one must be a VERY careful and detail-oriented researcher. Thankfully, the attribution I had to kill wasn’t to remove the artist; I was forced to remove the attribution to an event because it doesn’t appear that much research took place before the attribution was made.

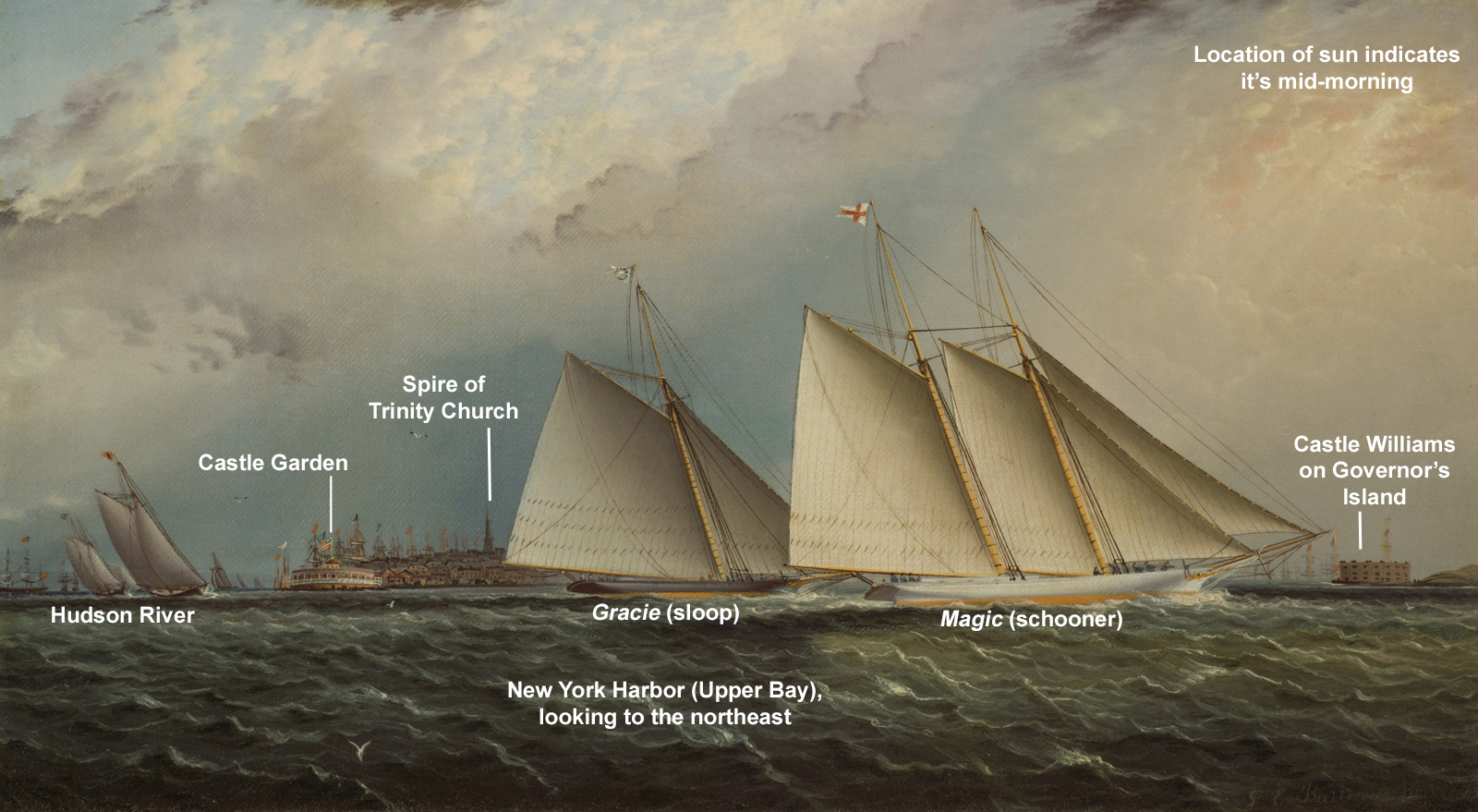

The affected work is a beautiful painting by marine artist James Edward Buttersworth. It depicts the schooner Magic and sloop Gracie leading a fleet of six yachts down the Hudson River and around the tip of Manhattan on a partly cloudy morning (we know it’s morning because of the position of the sun). A fairly famous piece, this painting graced the cover of the 1994 reprint of Rudolph J. Schaefer’s seminal work “J. E. Buttersworth 19th-Century Marine Painter.” At some point in the past, probably sometime before 1975, the scene was determined to be the annual regatta of the New York Yacht Club held on June 22, 1871. The slow and painful death of this attribution began when I was asked to provide historical details about the painting so it could be intelligently discussed during special events.

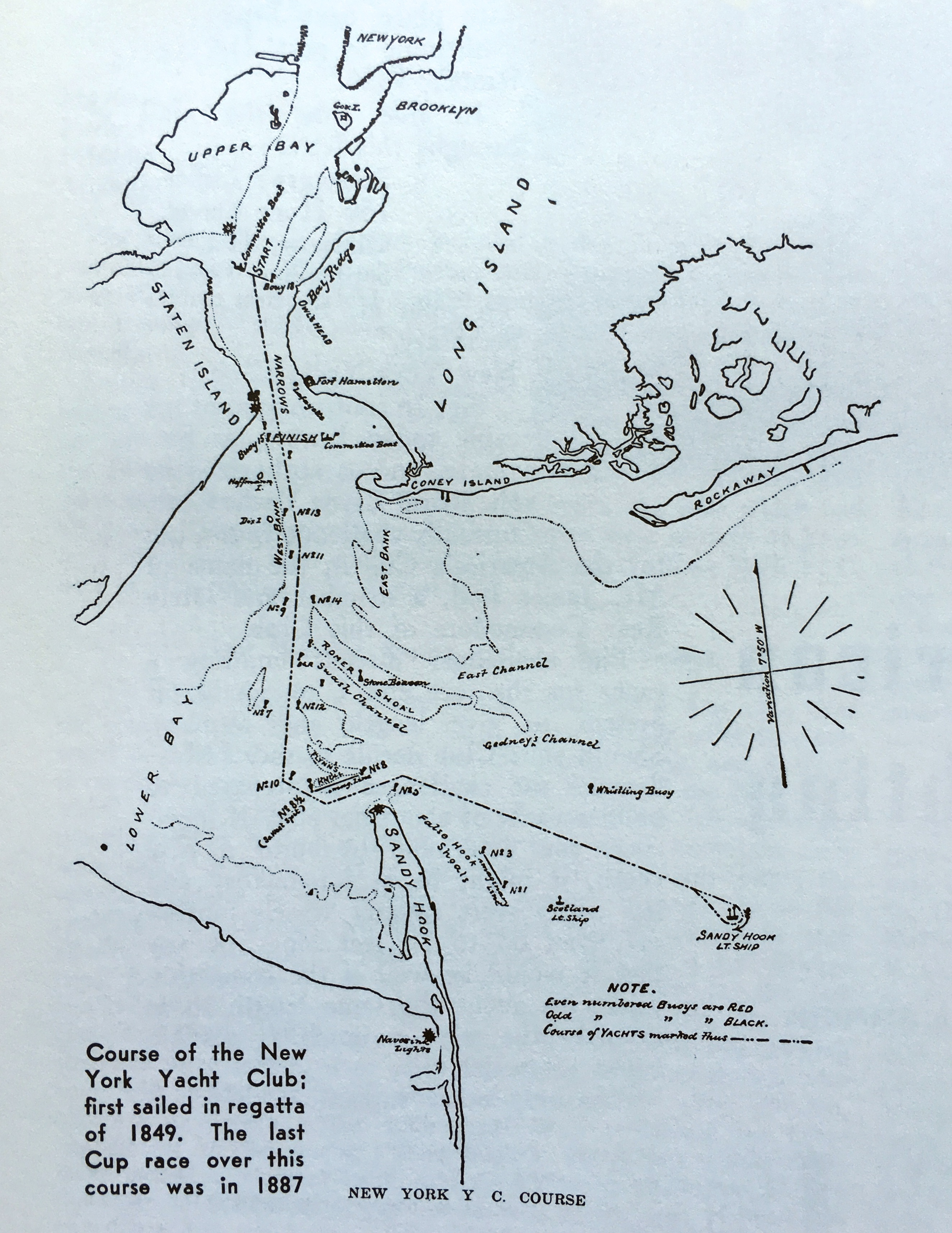

Since the event supposedly depicted a specific New York Yacht Club annual regatta I headed to Newspapers.com to locate a period description of the event and immediately ran into a problem. While my knowledge of the geography of New York and the history of the New York Yacht Club wouldn’t fill a thimble, it was obvious from the descriptions in the New York Times and New York Daily Herald that the 1871 race didn’t occur anywhere near the tip of Manhattan.

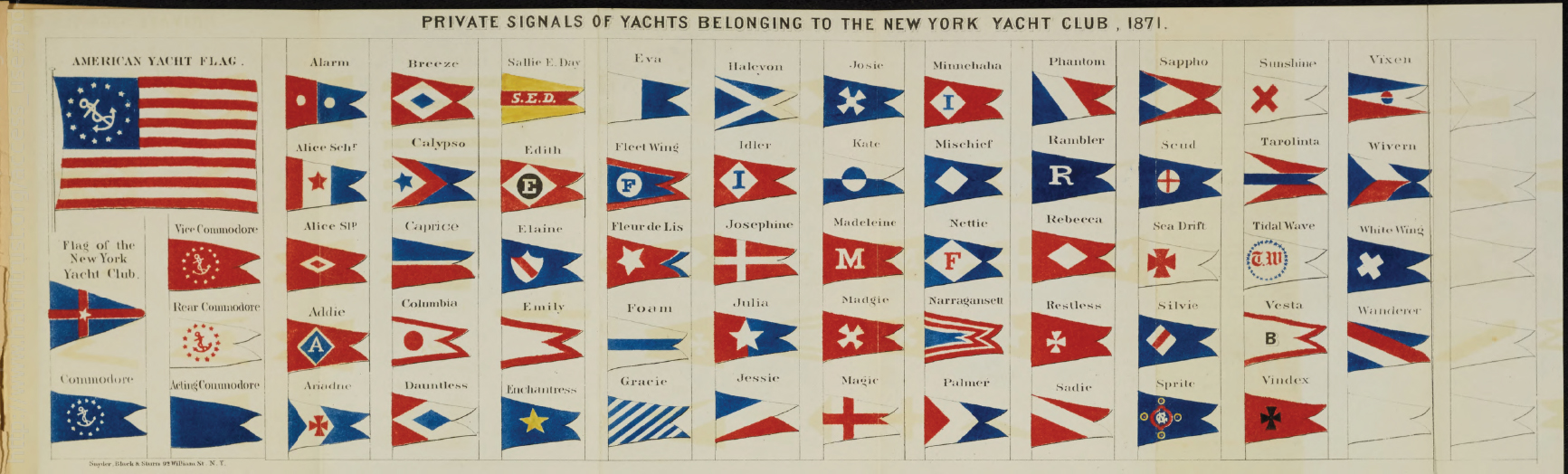

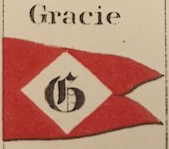

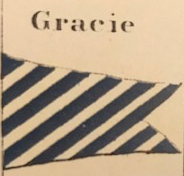

Stumped, I decided to look at the private signals on the two central vessels and, yet again, ran into a problem. While the signal flying on Magic is correct for one of its owners (actor J. Lester Wallack), the signal flying on Gracie is not. According to the chart of private signals published in the “Constitution, by-laws, sailing regulations, & etc. of the New York Yacht Club” Gracie’s signal during the 1871 race would have been a swallowtail burgee with diagonal blue and white stripes. Buttersworth shows Gracie with a white swallowtail burgee with a circle of blue stars.

At this point I decided that having thrown myself into the deep end of the pool with a couple of bricks tied to my feet required yelling for a couple of lifeguards. I started with friend R. Steven Tsuchiya, my go to expert for all things America’s Cup and New York Yacht Club. Steve has a big brain and is always supremely nice and patient when answering my many stupid questions. Over the course of several days we had some conversations that were HIGHLY enlightening. The information I learned from Steve is invaluable and has taught me how to “read” the many images in our collection that show sailing and yachting events in the New York area.

First, Steve gave me a geography lesson. When viewing the painting we are looking northeast across Upper New York Bay. Castle Williams sits at the right on the northwest corner of Governor’s Island. Castle Garden sits at the left between Gracie and the next closest yacht. The tall spire closest to Gracie’s stern is Trinity Church.

Steve’s next lessons centered on the New York Yacht Club. First, and thankfully, Steve agreed that the location of the scene at the tip of Manhattan ruled out the 1871 NYYC annual regatta as the event being depicted. According to Steve, by the late 1850s or early 1860s the New York Yacht Club, and many other clubs, no longer raced mid to large sized yachts on the Hudson River and Upper New York Bay because the area was too congested with commercial traffic. To make absolutely certain, we scoured the New York newspapers for details of yacht club races that occurred in the area Buttersworth depicts and couldn’t find any. The closest races I could find were conducted by the Columbia Yacht Club which started their races (at least between 1868 and 1874) at 57th Street, but they ran UP the Hudson not down.

With the removal of the attribution I faced the hurdle of reinterpreting the scene. Looking at the positions and attitudes of the yachts it was natural to assume the yachts are racing. Before fussing with me about these two boats being different classes let me just add that in NYYC annual regattas of the 1870s sloops and schooners competed in different classes for different prizes but they raced simultaneously. So, it is feasible that Magic and Gracie could be shown adjacent to each other during a race despite being different types of vessels.

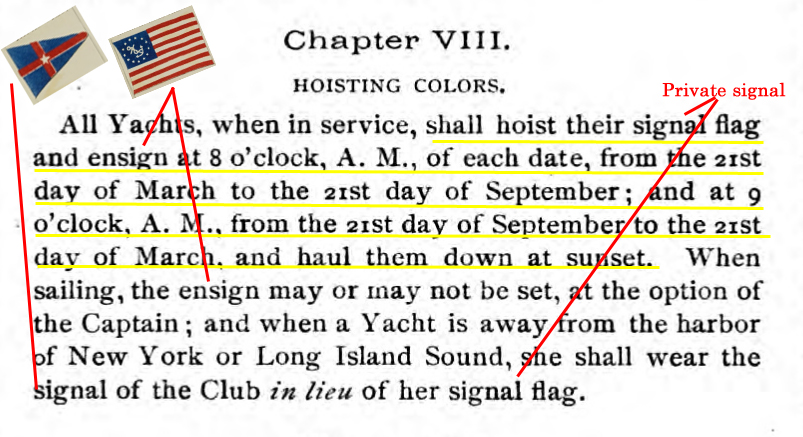

From my conversations with Steve I assumed the presence of private signals automatically indicated the vessels were racing. I also assumed that if Buttersworth wanted the scene to reflect the boats enjoying a recreational sail on the harbor he would have shown them flying yacht club burgees. We all know what happens when someone “assumes” things so I decided to read the New York Yacht Club’s 1871 year book. Have you ever read a 19th century NYYC year book? Ugh, don’t…I read it several times and walked away still unsure if I understood everything correctly.

Yet again, Steve came to my rescue (although he jumped over the hurdle while I merely crawled underneath of it). Like me, he also read the rules. Unlike me, he actually understood what was being said! What he discovered was that in 1871 New York Yacht Club vessels were required to fly their private signal when “in service” (in other words when racing OR cruising with the owner or owner’s representative on board). But, vessels flew the club signal (the club burgee in today’s parlance) in lieu of the private signal when they were away from “New York harbor or Long Island Sound.” SO, we can’t assume the presence of the private signals alone is an indication of a race in progress. That being said, looking at the positions of the yachts Steve and I are both pretty confident that Buttersworth intended for us to view this as a racing scene.

So, now we know everything we need to about private signals. Or do we? As I mentioned earlier, the private signals shown on the yachts present a real problem in their current configuration. Magic is flying the private signal of J. Lester Wallack which should automatically date the painting to 1871–the only year Wallack owned her. Buttersworth, however, regularly and incorrectly used Wallack’s signal (a white swallowtail burgee with red cross) to identify Magic even when someone other than Wallack owned the vessel. The most notable discrepancies can be seen in some of his depictions of the first America’s Cup defense in 1870. At that time, Magic, the winner of the contest, was owned by Franklin Osgood and his signal was a white swallowtail burgee with red border and a red ball at the center–sometimes Mr. B uses the correct signal for Magic, sometimes he doesn’t.

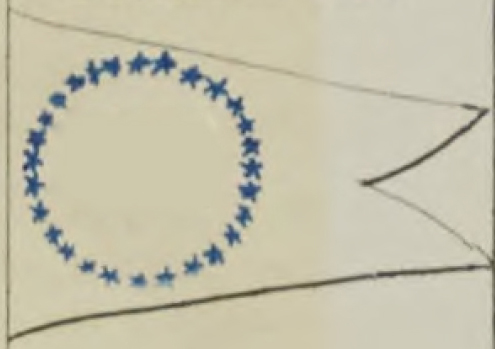

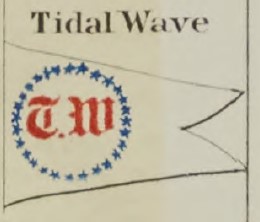

But it’s Gracie’s signal that poses the biggest problem and it’s where I had to call in my other lifeguard–this time in the form of Alice Dickinson, curator at the New York Yacht Club. During our initial conversations, Steve and I noted the similarity of Buttersworth’s signal on Gracie to one used by William Voorhis to identify his schooner Tidal Wave (a white field with a circle of blue stars with the letters T.W. in the center). Did Voorhis use a slightly different version of this flag on Gracie? Did one of the other owners of Gracie use the flag Buttersworth depicts? The only way to find out was to review the NYYC year books which neither Steve nor I had immediate access to. Alice graciously stepped in to help.

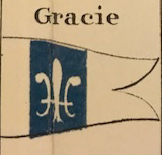

Starting with the 1868 to 1873 time period Alice reviewed the year books and determined that none of the owners used the signal Buttersworth depicts. In 1868 and 1869 Gracie was owned by William Voorhis and he used this signal:

In 1870 and 1871 Gracie was owned by H. W. Johnson and William Krebs and they used this signal:

In 1872 Gracie was owned by Samuel J. Colgate. Here’s his signal:

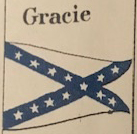

And finally, in 1873 owner John R. Waller flew this signal on Gracie:

Did you see a circle of blue stars on a white field? I certainly didn’t. So what the heck is going on here? Alice began checking over thirty years of year books–from 1850 all the way to 1881 and what did she discover? The signal Buttersworth shows was never used–at least not by any member of the New York Yacht Club. Oookay…now what?

Questions started forming rapidly.

If Buttersworth wished to depict the vessel while it was owned by the well-known Voorhis rather than the less familiar Johnson and Krebs why not use Voorhis’s signal for Gracie?

Is it possible that Buttersworth was unsure of Gracie’s signal while Voorhis owned her so he used a little artistic license to create a signal that would loosely tie the sloop to Voorhis?

Did he just willy-nilly make the signal up not caring whether or not it provided an identification of the vessel? If he did, why did he make sure Magic was clearly identified?

Is the vessel depicted actually Gracie or did someone just make a huge assumption? Would Buttersworth create a painting showing a celebrated vessel racing against an unknown vessel? Seems unlikely.

Only Mr. B knows for sure.

So where does this leave me? Taking everything into account Steve and I feel pretty confident making a few assumptions about the painting. First, the attribution to the June 22, 1871 annual regatta as an accurate depiction is D…E…A…D. Go directly to jail. Do not pass Go. Do not collect $200. Buttersworth may have intended to show the 1871 annual regatta but used a generous helping of artistic license and placed the race on the Upper Bay in order to feature recognized vessels and iconic New York City buildings.

Second, while the beautiful little, black-hulled sloop pictured could be another, don’t you think Buttersworth would have chosen to depict Magic racing against an equally well-known vessel? I do. His loose interpretation of Voorhis’s Tidal Wave signal on the main mast seems a little bit like waving a red flag in front of a bull. I really think he wanted people to recognize the sloop as Gracie.

Third, considering the owners, the public’s familiarity with the vessels, the signals shown and Buttersworth’s known boo-boo’s when it came to depicting them, I feel fairly confident in revising the date of the painting to a slightly broader 1868 to 1872. This time period covers the years Gracie was built and owned by Voorhis while also covering the ownership of Magic by Osgood and Wallack. I guess I could be really conservative and push the dates out to 1868 to 1894 (the year Buttersworth died), but the artistic quality of the painting makes me lean more towards his earlier style of painting rather than the looser, painterly-style of his later works.

And finally, this painting likely wasn’t created in response to a commission by one of the owners. While I suppose Wallack could have made the commission it seems unlikely as he only owned Magic for a year and participated in the June annual regatta and August squadron cruise to Boston but didn’t appear to win any races with her.

It seems fairly certain that Buttersworth simply intended to create a beautiful, albeit fictional scene showing two famous yachts in an identifiable and picturesque setting merely because he knew it would be well received by his audience and thus highly marketable. And you know what? I can live with that.

Acknowledgement: I can’t thank Alice Dickinson and my partner in crime Steve Tsuchiya enough for all of their help in researching and writing this post. You guys rock!