Hampton Roads is a pretty amazing place. Besides being one of the most important ports on the East Coast, it’s also been a cradle for innovation. Some of the “firsts” that occurred in Hampton Roads were Eugene Ely’s first flight of an airplane off the deck of a ship (USS Birmingham) and Robert Gilruth’s (of NASA fame) designing, building and sailing of the world’s first hydrofoiling sailboat. This year I learned about another first, Hampton Roads is considered to be the birthplace of underwater photography* and it led to the first successful underwater motion pictures.

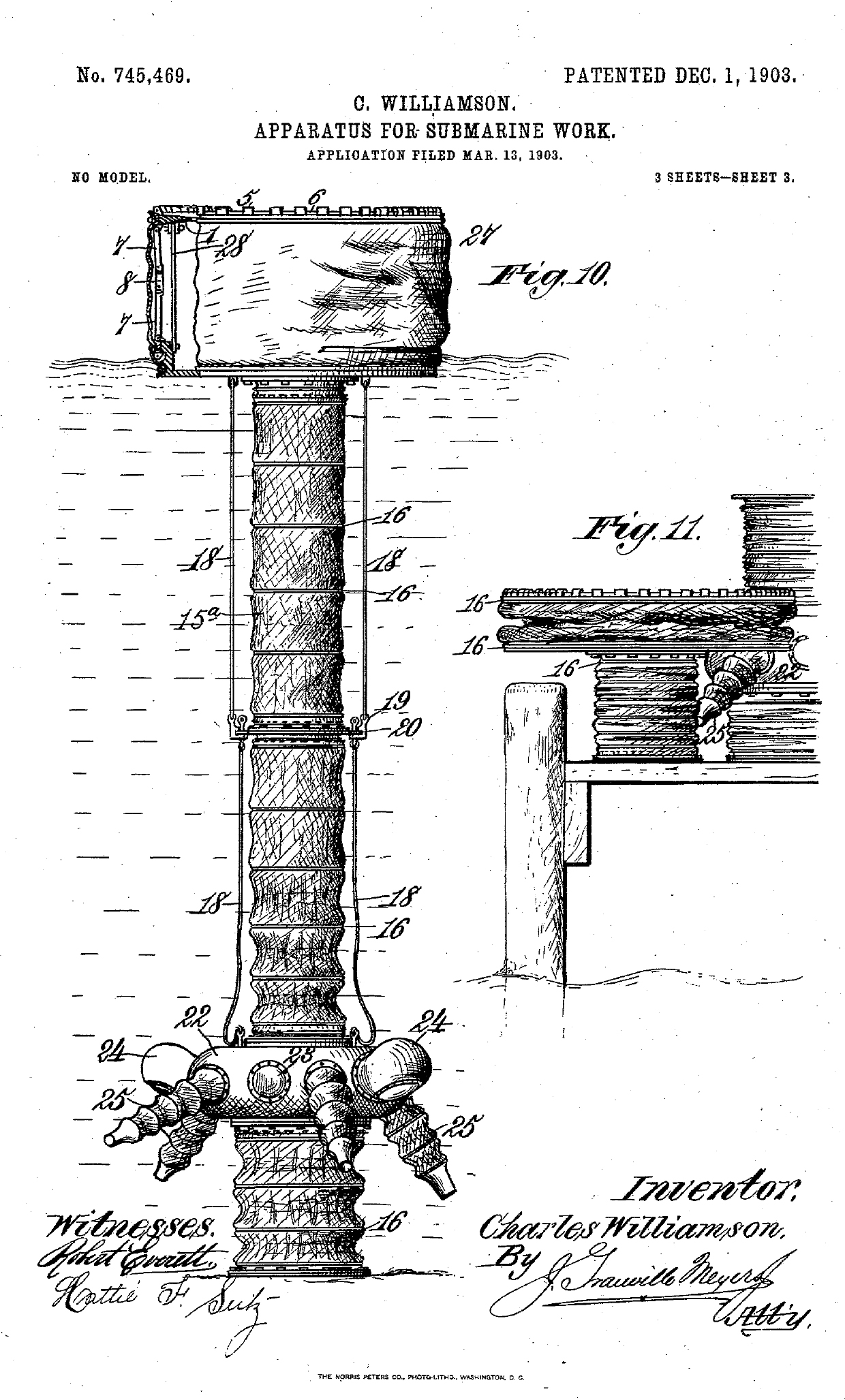

It all started when Captain Charles Williamson, a merchant mariner who was also a bit of an inventor, moved his family from England to Vermont to Norfolk. Among Williamson’s many inventions were a folding baby carriage and a signalling system for ships. In 1903 he patented an “apparatus for submarine work” which was essentially a waterproof tube that enabled underwater repair, salvage work, commercial harvesting of items on the seafloor or even underwater tourism (in 1911 he patented a “submarine pleasure apparatus” based on the same idea).

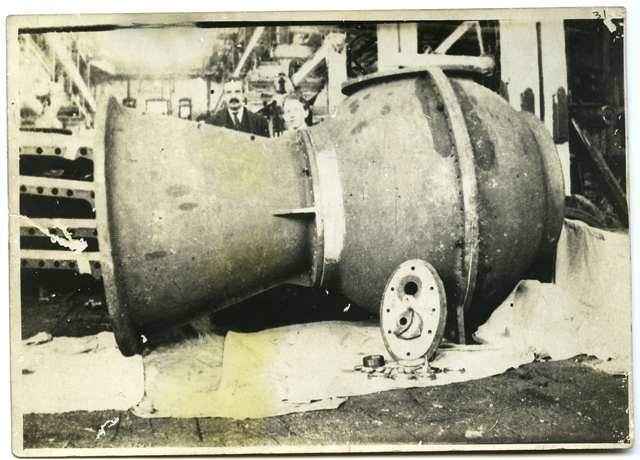

Williamson’s 3-foot diameter tube was made of a series of concentric, interlocking iron rings covered with a waterproof fabric of canvas and rubber. It was strong enough to resist the pressure of the water but pliable and flexible enough to move with the current (or the boat). The tube, which could be extended up to 250 feet in length, stretched between a specially outfitted barge and an observation/work chamber and facilitated communication, provided fresh air and created a passageway large enough for a man to climb through. Like most of Captain Williamson’s other inventions, the “Apparatus for Submarine Work” was never a commercial success, but what his son ended up using it for changed the world forever!

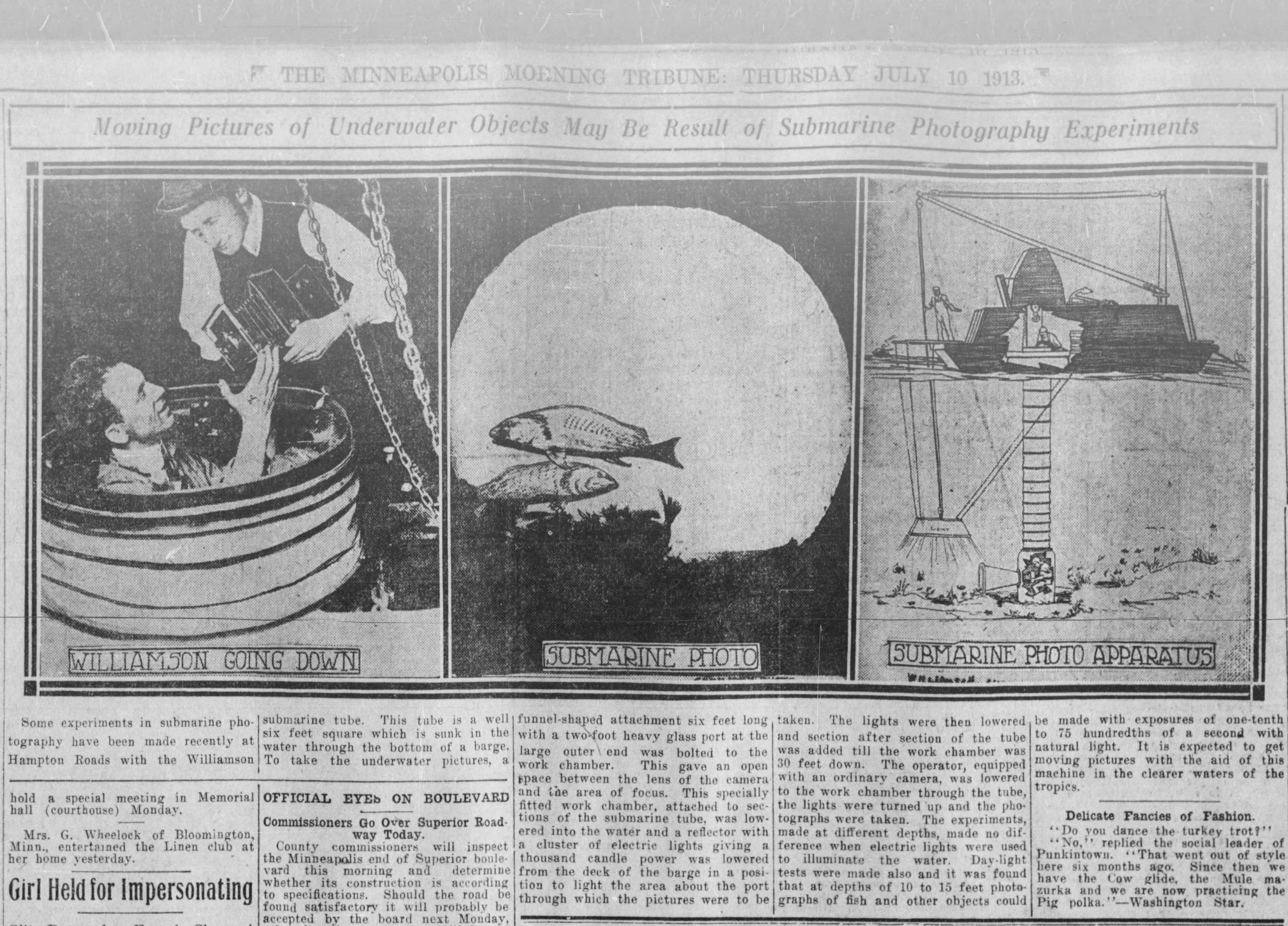

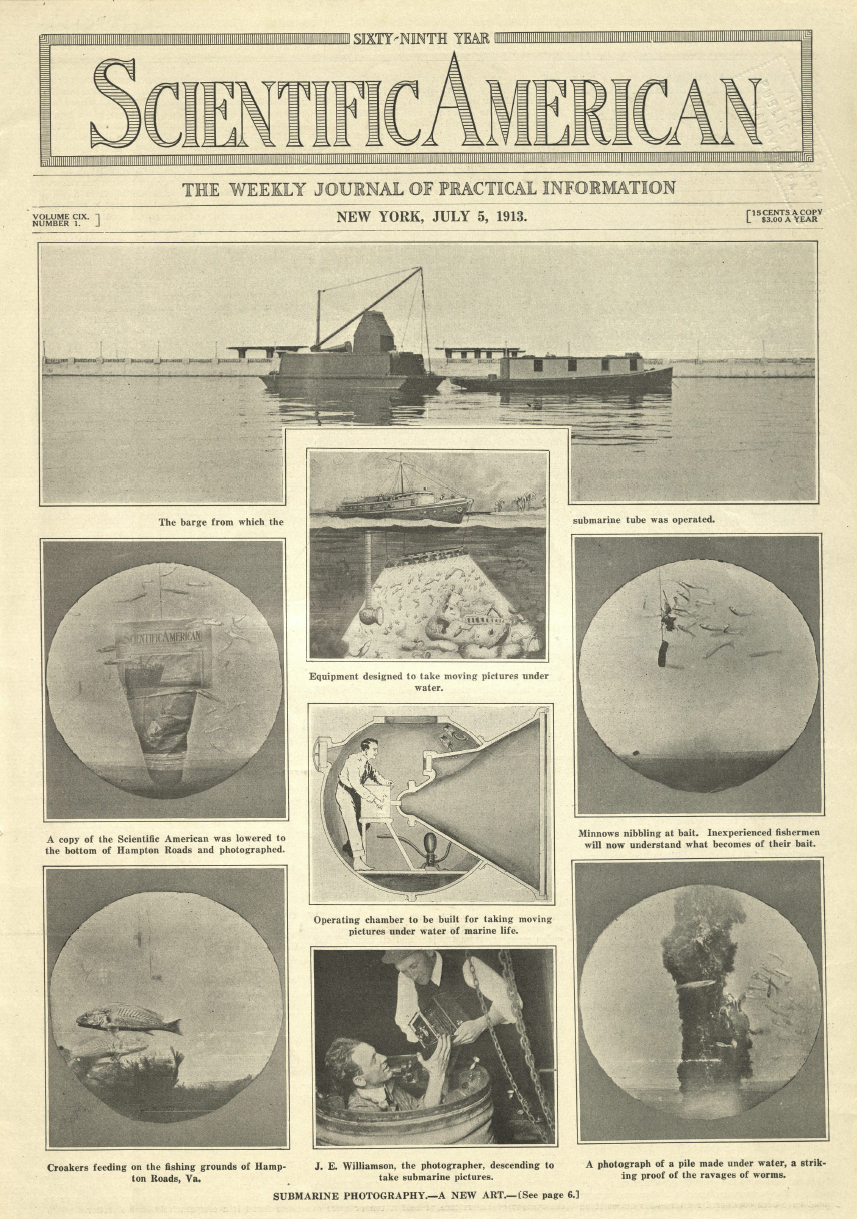

In 1912, while working as a newspaper cartoonist, photographer and periodic reporter with the Philadelphia Record and Virginian-Pilot, John Ernest Williamson came up with the idea of trying to use his dad’s “Apparatus for Submarine Work” to take photographs under water. With the help of his brother George, he enlarged the work chamber and viewing ports at the base of the tube to facilitate a camera. During their initial test in Hampton Roads they discovered the water was so murky it limited visibility to just a few feet (Really? I can’t believe they were surprised by this our water isn’t exactly “tropical” looking around here! Sometimes you can’t even see further than two inches!). To extend visibility they engineering a bank of tungsten electric lamps so they could be turned on and remain lit underwater.

For their next test, the lights were hung off the back of their boat so they would illuminate the area in front of the observation window. Once Williamson was in position with his camera, a baited line was lowered in front of the window and the lights were turned on. Within moments the work chamber was surrounded by thousands of fish. John Ernest spent the afternoon taking pictures not knowing if they would turn out but a few hours in a darkroom yielded some great underwater photographs. One image even showed a Scientific American magazine!

While in the dark room Williamson realized that if photographs could be taken at the exposure he had used (1/50th of a second or less) then under similar conditions he might also be able to take underwater motion pictures (the movie industry was in its infancy in 1913 and everybody was fascinated by it and trying to figure out how to exploit it). Williamson approached his editor at the Virginian-Pilot, Keville Glennan, about his photographs and his motion picture idea and Glennan immediately recognized the importance of what the Williamson brothers had accomplished. The following Sunday, he ran a full page article detailing the achievement.

Within days of the article’s publication, hundreds of letters and telegrams from magazines and newspapers around the country began arriving. Among them was an invitation to display Williamson’s photographs at the First International Motion Picture Exposition in New York. The images were the hit of the show and many of the attendees offered to help fund an expedition to the Bahamas to experiment with underwater motion pictures. One of the investors, Charles J. Hite of the Thanhouser Film Corporation, supplied a motion picture camera, a “cinematograph operator” (Carl Louis Gregory), all the necessary film, and a promise to market the completed film.

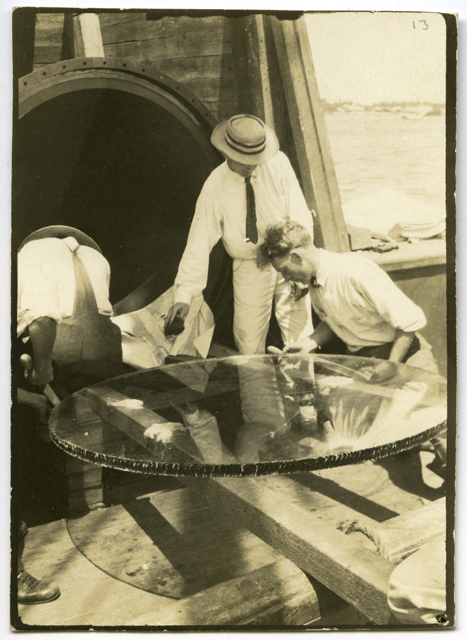

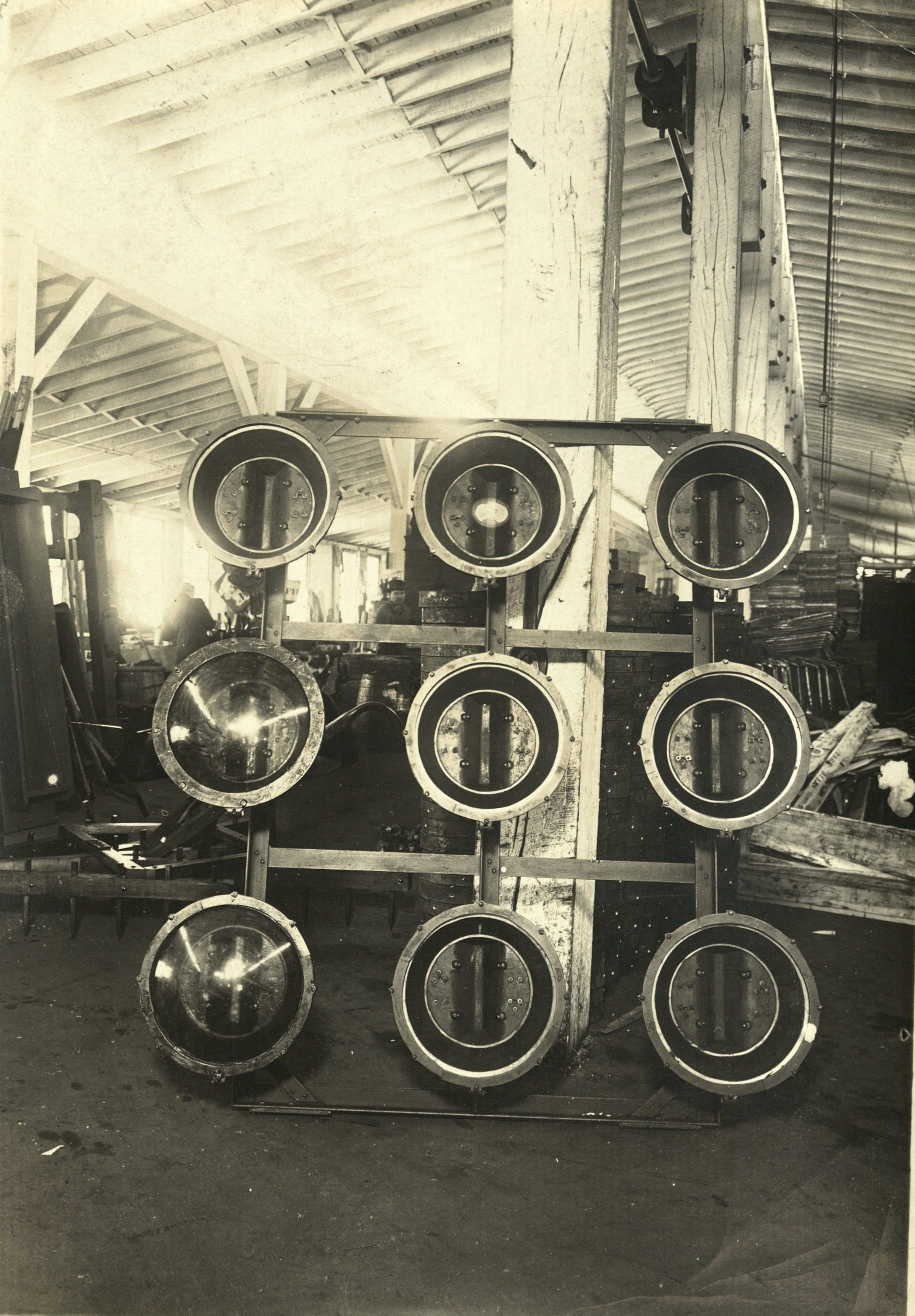

In preparation for the expedition, John Ernest and George devised a new observation chamber which they called a “photosphere.” It was a 6×10-foot steel globe with a large funnel-shaped window on one side. The window, made in France, was an inch-and-a-half thick and five feet in diameter. They also had optical experts at the Rochester Institute of Technology develop new camera lenses and film for the expedition and acquired nine 2,400 candlepower Cooper-Hewitt mercury vapour lamps. As it turned out, the lamps were rarely needed since sunlight easily reached depths up to 150 feet and water clarity allowed viewing up to 150 to 200 feet.

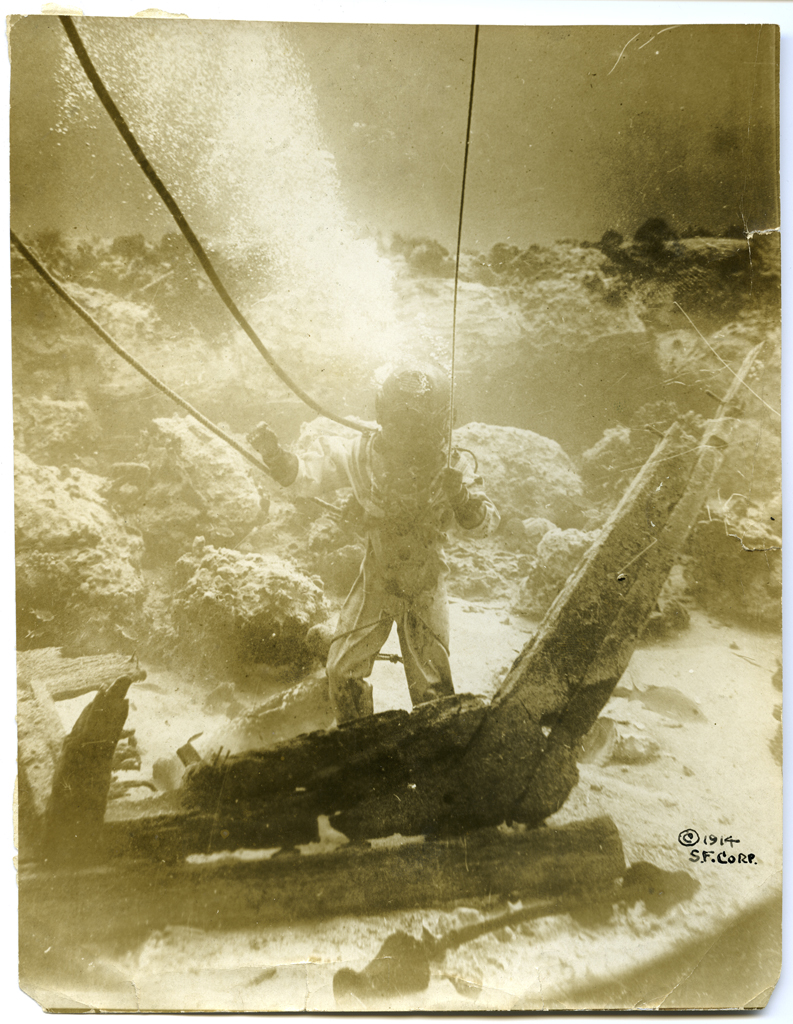

After arriving in Nassau, the team spent a month building a barge 40’ long and 16’ wide with a large well at the center to house the photosphere. It was christened the Jules Verne and the power boat used to tow it was called Nautilus. [Do you get the impression Williamson loved Verne and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea?] Between April 10 and June 10th, 1914, Gregory shot more than 20,000 feet of film. From that footage the Thanhouser Film Corporation created two films for Williamson’s Submarine Film Company: Thirty Leagues under the Sea and Terrors of the Deep (also known as At the bottom of the Ocean). These two one-hour films have apparently been lost, but a 13 minute excerpt of the film survives as In De Trophische Zee.

Right off the bat you’ll probably notice something odd in the film–a horse. Because the Williamson’s were interested in the entertainment value of their film they promised their investors they would include a fight between a native diver and a shark. In order to lure sharks to the filming area they searched far and wide for the perfect bait–a horse that had been condemned to be shot. On the day of the filming the horse’s owner delivered the horse but there was one problem, it was still alive–apparently no animal could be shot without an official British government permit. A short time later, a guard of formally attired Royal Bahamas police arrived on the scene, examined the horse and concurred that it was indeed lame. At that point, and apparently “with great formality,” the officer in charge read the permit to the horse. Once the police were convinced the horse understood its fate, it was shot. [Now why in the hell didn’t they film THIS event (not the shooting part obviously, yuck)? I want to see the horse’s reaction when the policeman told him was going to die!]

Clips from “In de Trophische Zee” from the Nederlands Filmmuseum.

With the horse converted to bait, Williamson’s crew suspended it from a boom Jules Verne, lured the sharks to the area, and then allowed the bait to sink to the area just above the photosphere’s window. While Williamson operated the camera, each of the native divers tried to kill a shark. One diver managed to kill a shark but the uncooperative animal dragged the diver out of the camera’s range. Frustrated, John Ernest (who was obviously a lunatic) decided HE would play the role of shark killer to ensure the action was caught on film. Amazingly he killed a shark and didn’t lose any body parts in the process.

As you might expect, this first film showing underwater scenes was an instant success. The Williamson brothers immediately realized that a film of a fictional story would be even more popular and might even make some money. The most obvious story for this endeavor was the enormously popular Jules Verne novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. The Williamson Submarine Motion Pictures Company formed a partnership with Universal Film Manufacturing Company (Universal Pictures) and the Williamson’s returned to the Bahamas in the spring of 1916 to begin filming.

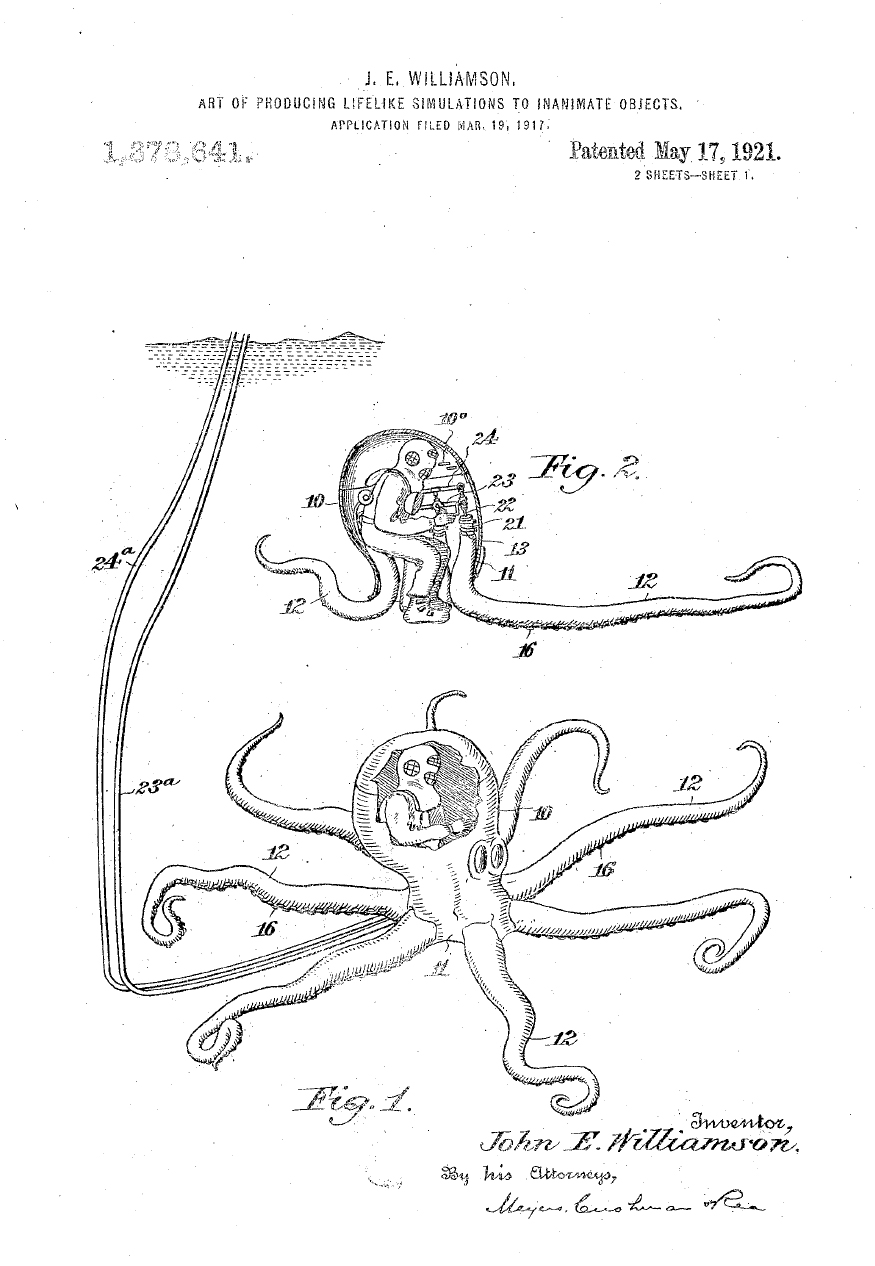

Ever the showman, Williamson wanted to include the scene of Captain Nemo’s battle with a giant octopus. Since there was no way he was going to find a live creature large enough and cooperative enough to act as he wished he decided to build one. To make the tentacles writhe, squirm, reach out and grab objects, draw them in and then coil around them, Williamson used a rubber tube surrounded by tapered springs that could be inflated with compressed air to simulate the arm reaching out. As the tube deflated, the springs would drawn the arm back in. The structure was covered with a material that represented the octopus’s skin and rubber balls of graduated sizes were cut in half to represent the sucking disks. It worked so well, Williamson actually patented his idea!

Just to make sure the scene looked realistic Williamson didn’t tell the diver acting in the scene that the octopus was going to grab him and nearly drown him before he was rescued by “Captain Nemo.” He nearly gave the guy heart failure. After shark killing and near death by fake octopus I’m not so sure I’d be willing to do any more acting for this guy.

The following September the world’s first motion picture film containing scenes shot underwater was released. Unfortunately, the first talking motion picture was released right around the same time so the film didn’t do as well at the box office as they’d hoped. Over the course of the next forty years John Ernest filmed underwater scenes for about eleven movies and while his work didn’t advance the technology of underwater cameras or diving equipment or offer new scientific insights, it did provide the impetus for the expanded use of undersea photography and film making.

*It was actually French biologist Louis Boutan who successfully the first underwater photographs in the late 1890s at Banyuls-Sur-Mer–but it was in really shallow water! Williamson’s pictures were taken at a depth of thirty feet.