On April 19, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln declared a blockade of the Confederate coastline from the Chesapeake Bay to the Rio Grande. Wilmington, North Carolina, eventually became the leading haven for blockade runners on the east coast. Located 18 miles up the Cape Fear River from the Atlantic Ocean, Wilmington was only 570 miles from Nassau in the Bahamas, and 674 miles from Bermuda.

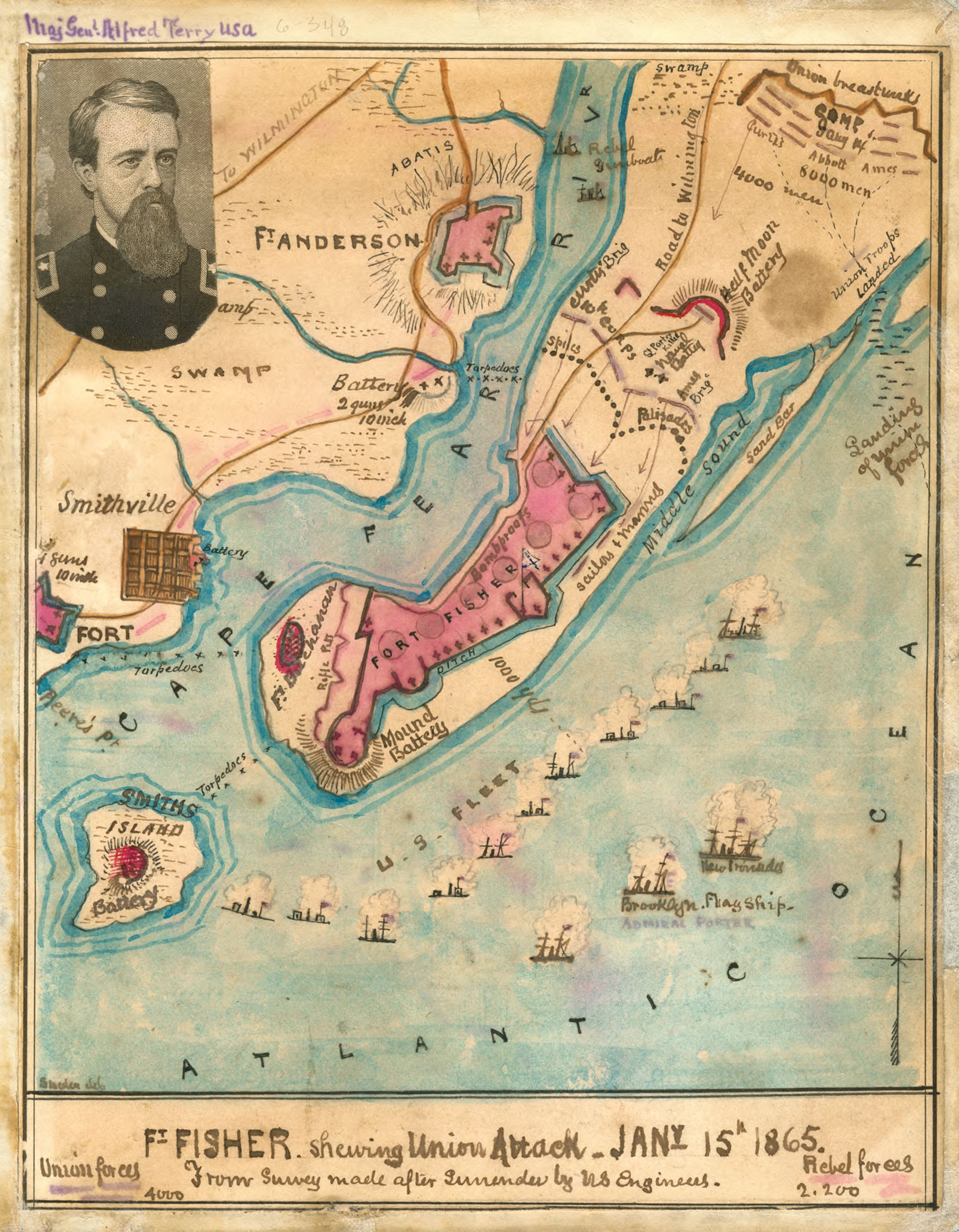

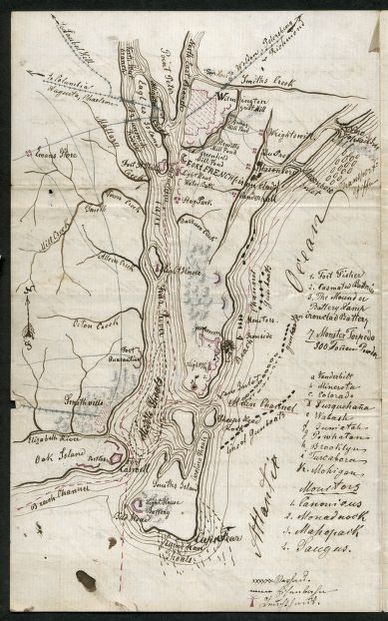

Several factors facilitated the port’s blockade-running success. Wilmington was situated as an Atlantic railhead for major railroads leading up to Virginia and inland to Charlotte, North Carolina. Most importantly, the Cape Fear River had two entrances: the Old Inlet and the New Inlet; and there were major shoals off these entrances, including Frying Pan Shoals. This caused the US Navy to position their blockaders in a 50-mile arch. Even with almost 50 ships on station at any given time in 1864, the Union ships could not deter blockade runners from making dashes in and out of the Cape Fear.

BLOCKADE RUNNERS’ HAVEN

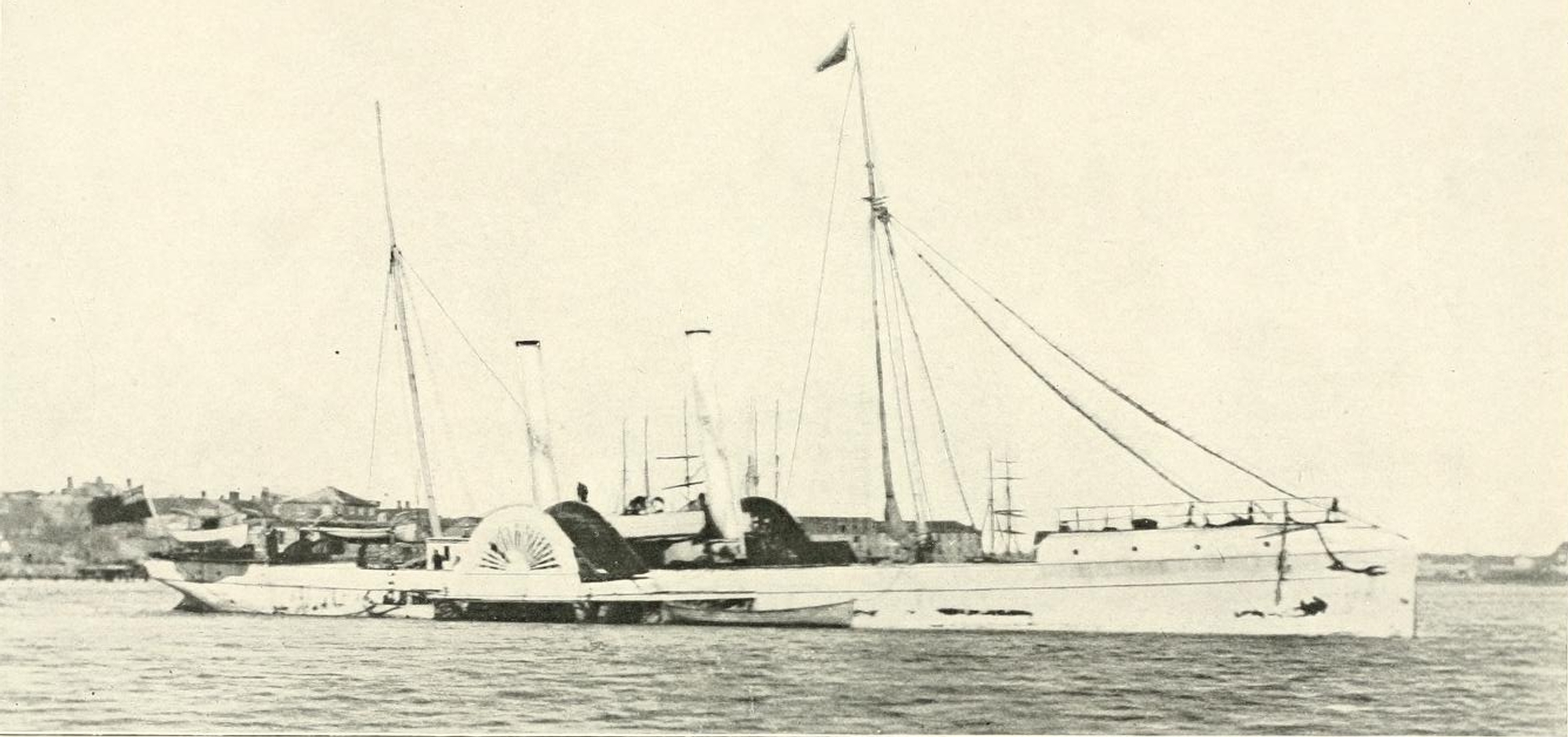

Blockade runners became a new style of vessel. They were purpose built to make the final voyage from places like St. Georges, Bermuda, into the Cape Fear. These shallow draft, low profile, sleek, gray colored, extremely fast vessels would use moonless nights, high tide, and stormy weather to slip past the guardian ships. Runners like Robert E. Lee made the passage into and out of the Cape Fear 21 times before being captured.

These ships brought into the Confederacy cannons, muskets, ammunition, medical supplies, clothing, and food as well as domestic goods. Profits as high as 700% were not unusual. During the last months of the war, runners brought into Wilmington: 69,000 rifles, 43 cannons, more than four tons of meat, 500,000 pairs of shoes, and a ton of saltpeter.

INNER RIVER DEFENSES

The importance of Wilmington prompted the Confederacy to construct an in-depth defensive system near the Cape Fear’s entrance. The main defenses were located near the river’s mouth, beginning with Fort Anderson. This fortification was built atop the colonial village of Brunswick Town. Originally named Fort St. Phillip, it was renamed in honor of General George Anderson, who was killed during the battle of Antietam. The fort’s main armament consisted of two 32-pounder rifles and seven 32-pounder smoothbores.

A few miles below Brunswick was the town of Smithfield (today’s Southport), North Carolina. It was defended by a four-gun battery known as Fort Pender, named for General William Dorsey Pender, who was killed at Gettysburg. The major defensive work was Fort Johnson. This fort was renamed Fort Branch, in honor of General Lawrence O’Bryan Branch (killed at Antietam), was originally built by the British. It was rebuilt by the Corps of Engineers several times between 1794 and 1812. The semi-circular front was built of tabby, and contained four guns. Smithfield, which had grown up around the fort, was a perfect anchorage for runners to watch the Union blockaders outside the Old and New Inlets, ideal for determining their best course of escape.

OLD INLET DEFENSES

The Old Inlet, also called the Western Bar, was defended on each side of this entrance. Oak Island, which juts out toward Frying Pan Shoals, featured Fort Caswell. Named for North Carolina’s Revolutionary War governor Richard Caswell, the fort was a pentagon-shaped brick fortification with 61 gun emplacements. In 1864, it was armed with 29 heavy seacoast Columbiads. The one-gun Battery Shaw and the 18-gun Fort Campbell completed Oak Island’s defenses.

Across the Old Inlet was Smith Island and its one major fortification on Bald Head Point, known as Fort Holmes (today’s Bald Head Island). Named for General Theophilus Holmes, this earthen fortification reached more than a mile in length; however, it was still under construction in December 1864.

GIBRALTAR OF THE SOUTH

The largest earthen fortification in the world was Fort Fisher, located on Federal (Confederate) Point. Fort Fisher was named in honor of Colonel Charles Lamb, who was killed during the First Battle of Manassas. The fort was initiated in 1861; however, limited progress was made until Colonel William Lamb assumed command on July 4, 1862. Lamb, a pre-war newspaper editor, was guided by West Point graduate and former member of the US Army Corps of Engineers Major General William Chase Henry Whiting.

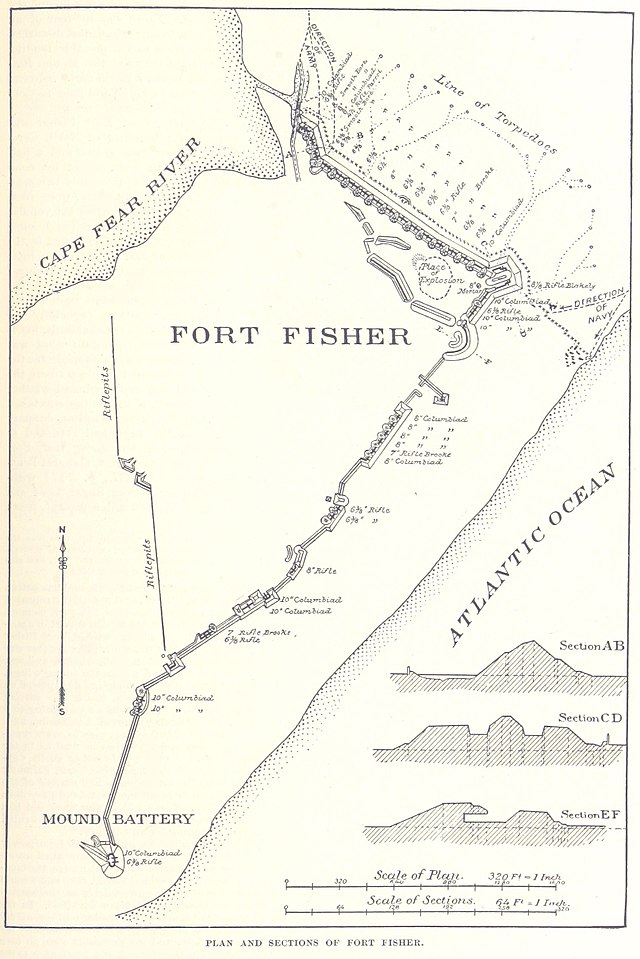

Between 1862 and late-1864, Fort Fisher was expanded into an enormous earthwork, stretching over a mile along the sea face and 1,800 feet along the land face. Both lines consisted of sod-covered mounds of sand, supported by heavy timbers; between them were gun platforms. Inside these 30-foot-wide mounds were bomb-proofs, magazines, a hospital, and Col. Lamb’s headquarters.

LAND AND SEA

The land face featured 15 traverses, 32 feet above sea level. This section of Fort Fisher had twelve 32-pounder rifles, two 10-inch Columbiads, one 7-inch Brooke rifle, four 8-inch Columbiads, two-24-pounder Coehorn mortars, and one 10-inch (sometimes referred to as an 8-inch) seacoast mortar.

The Sally Port (secure entrance to a fort with a series of doors or gates) was defended by one 3-inch Parrott rifle and one 12-pounder Napoleon. The land face had added protection from a 9-foot-tall stake fence. This palisade ran the entire length of the land face to the sea. In front of this fence were placed 24 torpedoes (mines) to disrupt any infantry advance against the fort. The land face ended with the massive Northeast Bastion, and next to it was the towering Pulpit Battery, armed with an innovative 8-inch Blakeley rifle.

The sea face continued toward Confederate Point with mounds and gun emplacements 20 to 30 feet above sea level. The armament was the best the Confederacy could assemble including: seven 10-inch Columbiads, four 32-pounder rifles, five 8-inch Columbiads, one 42-pounder rifle, and one 150-pounder Armstrong gun. The sea face ended with the 60-foot-high Mound Battery. This position featured one 10-inch Columbiad and one 32-pounder rifle, as well as a light beacon to guide blockade runners into the Cape Fear.

The entire defensive system ended with Battery Buchanan. This earthwork was named in honor of Admiral Franklin Buchanan and was staffed by naval personnel. The battery had four guns: two 10-inch Columbiads and two XI-inch Brooke smoothbores.

Colonel Lamb used his command of about 1,800 men along with as many as 600 enslaved persons to construct Fort Fisher. The Federals recognized that Wilmington needed to be closed. But they also realized the magnitude, strength, and extent of the Cape Fear defenses. Fort Fisher had to hold until the very end because General R.E. Lee’s army, outside Richmond, was completely reliant on this flow of war materiel and food. As 1864 neared to a close, Fort Fisher would be tested twice as the Federals strove to defeat the Confederacy.

This is part one of a three-part series about Fort Fisher by John V. Quarstein. “Butler and the Powder Boat Scheme” and “The Fall of Fort Fisher” will follow.

Note 1 “The Care and Preservation of Historic Tabby,” Lauren Sickels-Taves, Eastern Michigan University. http://ophelia.sdsu.edu:8080/henryford_org/03-25-2015/research/caring/tabby.aspx.html , accessed May 8, 2020. “Tabby refers to a unique, centuries old, southern U.S. coastal building material purportedly composed of equal proportions of homemade lime, sand, oyster shells and water.”

Excerpted from: CSS Virginia: Sink Before Surrender, John V. Quarstein. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2012; and A History of Ironclads: The Power of Iron Over Wood, John V. Quarstein. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2006.

Available in the Museum’s Web Shop: https://www.google.com/url?q=https://shop.marinersmuseum.org/sink-before-surrender-pb.html&sa=D&source=hangouts&ust=1587055613966000&usg=AFQjCNGlDlDHoLEWTXRLO71bPBmtARqV5A