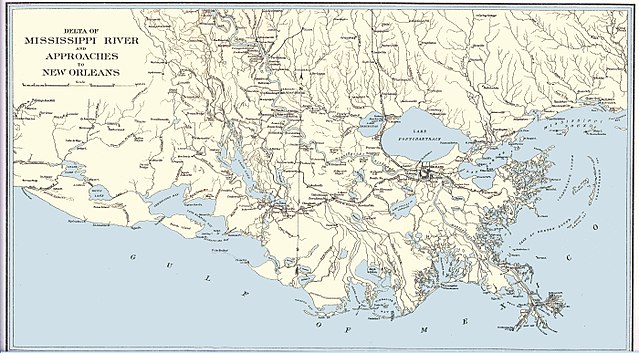

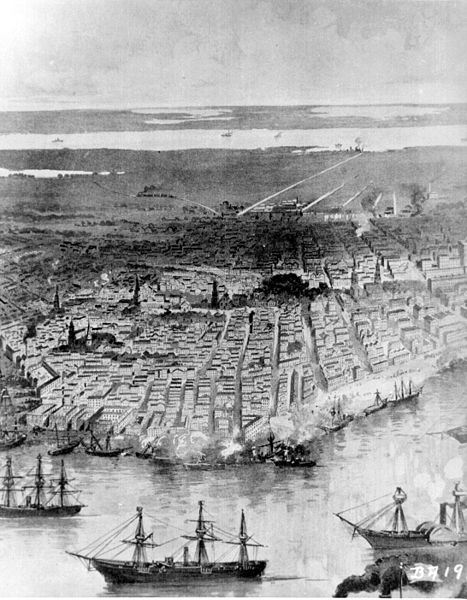

New Orleans was the largest city in the Confederacy with more than 120,000 inhabitants. This cosmopolitan community was a leading shipping, shipbuilding, and industrial center. The city controlled the commerce of the entire Mississippi Valley and its tributaries, like the Ohio, Missouri, and Red rivers. While it was ever so critical for the Confederacy to maintain control of this city, events elsewhere, especially in Tennessee, resulted in New Orleans having inadequate defenses and naval support. The city’s loss would have significant implications.

Confederate Naval Preparations

Much to the dismay of Major General Mansfield Lovell and Flag Officer George Hollins, New Orleans had been stripped of most of its soldiers, cannons, and warships. Many believed that the Federals would try to take New Orleans by way of Union forces coming down the Mississippi. Hollins argued, to a level of insubordination, that every effort possible be made to block the Union fleet access into the Mississippi River from the Gulf of Mexico. He advocated that as the Union ships were lightened to cross the bar into the Southwest passage, the Federals were very vulnerable to attack, and Hollins wished to do so. He created such an uproar that he was reassigned to Richmond, Virginia.

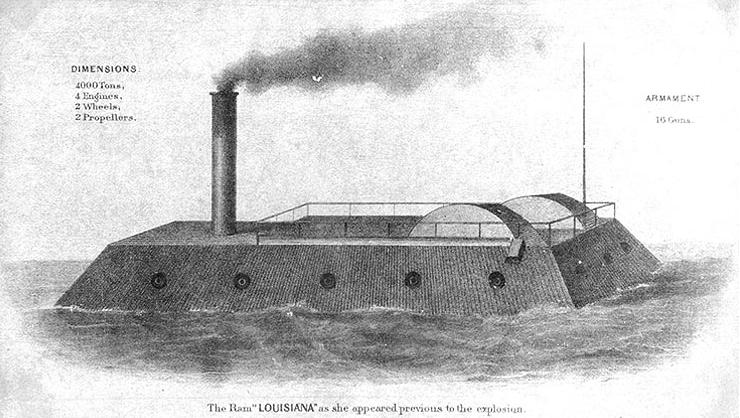

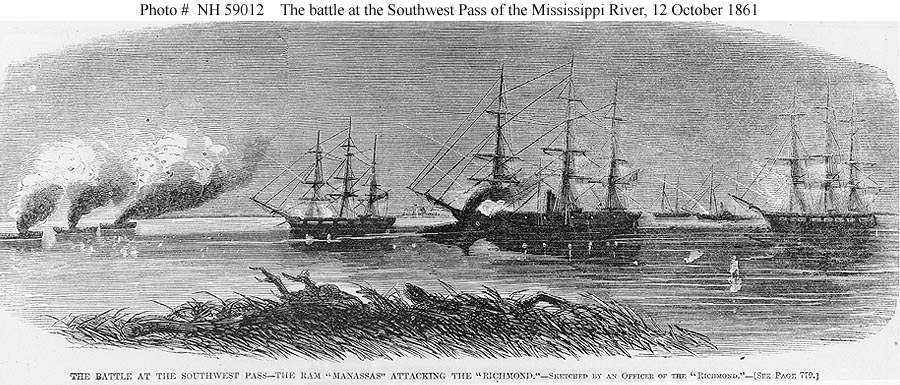

Hollins was replaced by the superintendent of the New Orleans Navy Yard, Commander William C. Whittle, who then turned over command of the Confederate naval forces to Commander John K. Mitchell. Mitchell was faced with a problematic command system that featured three different forces. Therefore, he was only in command of the gunboats CSS McRae and CSS Jackson, the ironclad CSS Manassas, and two nearly-finished ironclads, CSS Louisiana and CSS Mississippi.

Louisiana had a box-like casemate which contained two 7-inch Brooke rifles, four VIII-inch Dahlgrens, three IX-inch Dahlgrens, and seven 32-pounder shell guns. The 264 ft.- long vessel was launched in January 1862; however, its mode of power — two center paddlewheels and two screw propellers —was not operational. The ironclad would eventually be towed downriver, positioned near Fort Jackson. The CSS Mississippi, another huge ironclad, was still under construction when the Federal fleet made its attack.

There were two other naval commands. Louisiana had two warships, Governor Moore and General Quitman. The River Defense Fleet, which had been underwritten by the Confederate army, contained 14 cottonclads, commanded by Captain John A. Stephenson. Stephenson, who had constructed Manassas, refused to follow Commander John Mitchell’s orders. Consequently, New Orleans’s naval defense was weak, incomplete, and in disarray.

Confederate Fortifications

Robert Knox Sneden, artist. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

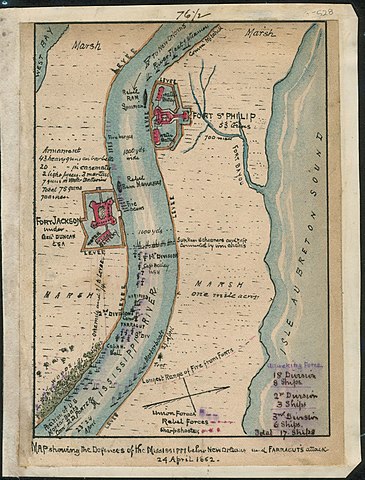

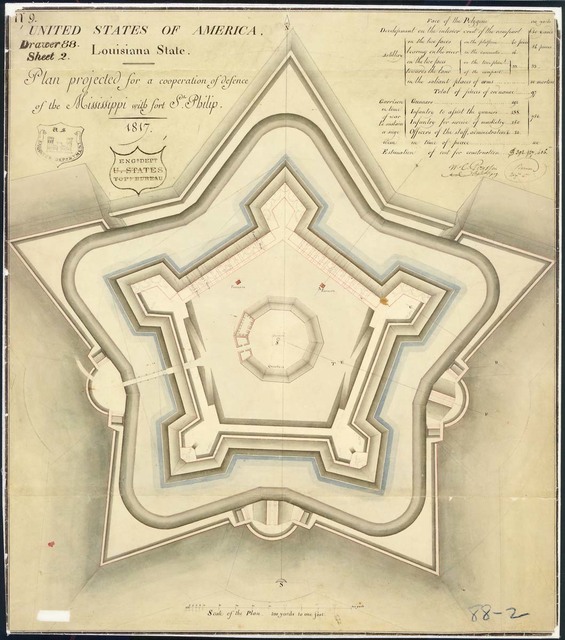

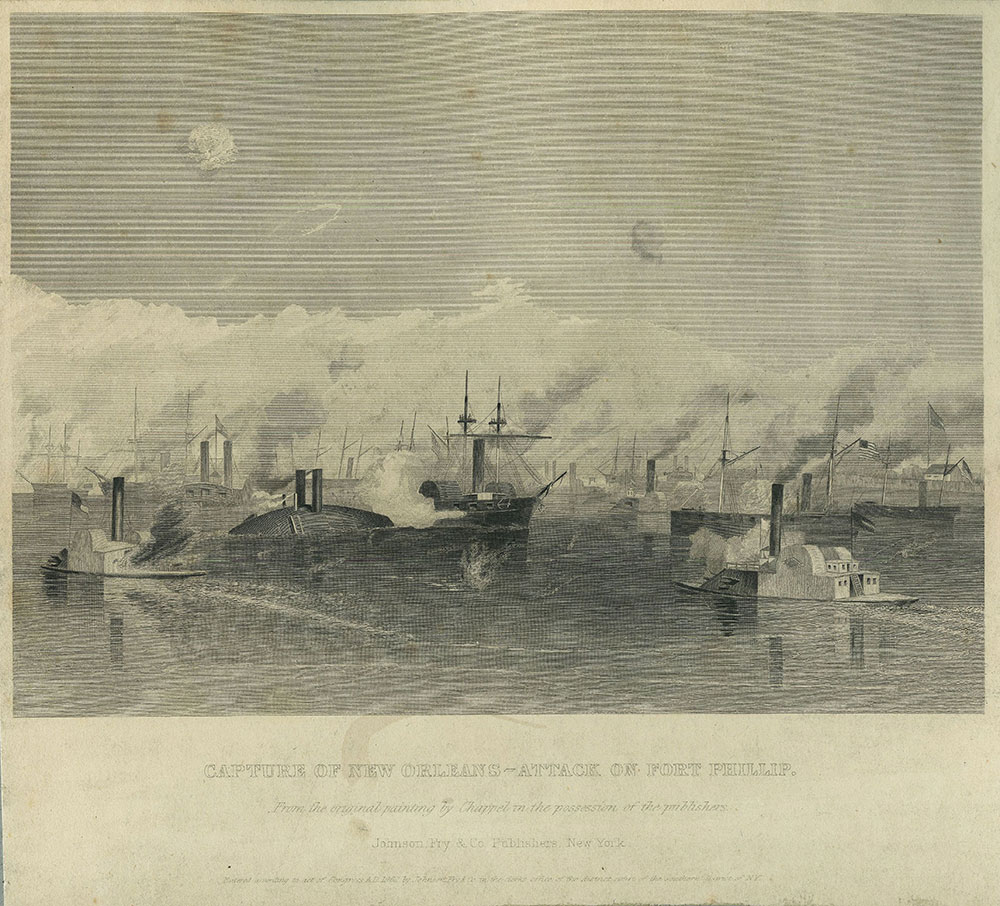

The primary defensive system protecting New Orleans was the pair of brick fortifications situated 75 miles downstream at Plaquemines Bend. Forts St. Philip and Jackson featured 177 cannons and an iron defensive chain to block ships from reaching the forts. Fort St. Philip (originally named Fort San Felipe) was built in 1795 during the Spanish occupation. When the United States occupied Louisiana, the fort was rebuilt in 1808. The brick fort was able to withstand the January 9 through 18, 1815, siege by British wooden sailing warships.

On the western side of the river situated diagonally from Fort St. Philip was Fort Jackson. Named for General Andrew Jackson, this star-shaped fort was begun in 1822 and completed in 1832. Brigadier General Johnson Kelly Duncan, an 1849 graduate of the United States Military Academy, commanded both forts which were located 40 miles upriver from the Gulf of Mexico.

https://catalog.archives.gov/

Union Plans

Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles began considering an operation against New Orleans from the Gulf of Mexico. He convinced President Abraham Lincoln to move forward with the operation shortly after the Union defeat during the Battle of the Head of Passes. Accordingly, in December 1861, the Gulf Blockading Squadron was divided into two commands: West Gulf Coast Blockading Squadron and East Gulf Coast Blockading Squadron.

On January 9, 1862, Captain David Glasgow Farragut was named commander of the West Gulf Coast Blockading Squadron. His goal? The capture of New Orleans. Farragut, who had been in the US Navy since he was nine years old, was assigned 19 ships to do this work. However, the flag officer believed, based on the success of Flag Officer S. F. DuPont at Port Royal Sound in November 1861, that steam powered ships could simply rush past fixed brick fortifications.

Once above forts St. Philip and Jackson, nothing could stop Farragut from reaching New Orleans. Farragut’s foster brother, Commander David Dixon Porter, was given a semi-independent command of 20 mortar schooners and six support ships. Each schooner carried a 13-inch seacoast mortar on a revolving mount. These guns and 30,000 shells were made by Fort Pitt Foundry of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, just for Porter’s use.

Although Farragut believed that the mortar boats would not have an impact upon the forts, Porter bragged to everyone who would listen that he would reduce the forts in 48 hours. In addition to these ships, Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler was given the command of 18,000 troops to besiege the forts. Farragut, troubled by Butler’s limitations as a combat commander, did not involve the general in his plans.

Union Preparations

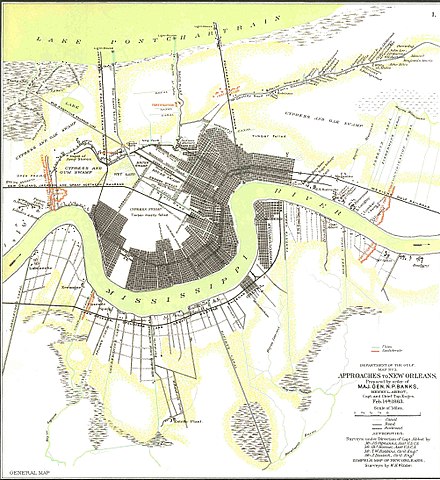

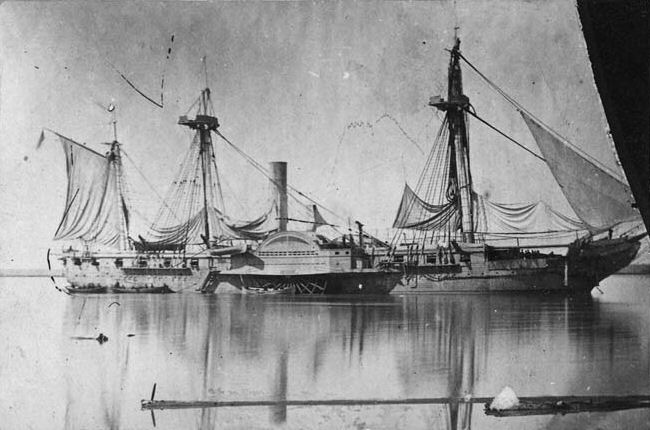

Farragut began assembling his fleet at Ship’s Island off the Mississippi coast on February 20, 1862. On March 18, he began to move his ships into the Mississippi River. The smaller gunboats and mortar schooners used the Pass a l’Outre.

The flag officer then sent his heavier ships, USS Hartford, Pensacola, Richmond, Brooklyn, Mississippi, and Colorado to use the Southwest Pass. This pass supposedly enabled ships with a draft of 18 feet to enter; yet, the water level was only 15 feet. Consequently, Farragut had to lighten all these vessels and use their steam power to push through the sand bar at the entrance to the pass. This was a very time consuming task. All his ships made it through except for the steam screw frigate USS Colorado. The frigate’s draft of 23 feet made it impossible to enter the Southwest Pass.

Photographer: Ascribed to McPherson & Oliver, Baton Rouge.

http://www.lib.lsu.edu/special/findaid/Suydam/sidewheeler1.html

MSS 1394015

The paddler USS Mississippi was able to cross the bar, thus becoming the largest ship ever to enter the Mississippi. Farragut noted, “now we are all right.” Farragut then tested and surveyed the ranges to reach the forts to determine where best to place the mortar fleet.

He ordered his ships to prepare for battle by lowering anchor chains amid ships and placing sandbags around machinery. With this makeshift armor, Farragut’s vessels were prepared to pass the forts.

Farragut then divided his squadron into three divisions:

- 1st Division (Red), commanded by Captain Theodorus Bailey: gunboat Cayuga, screw sloop Pensacola, sidewheeler frigate USS Mississippi, and several other gunboats with the purpose of passing Fort St. Philip;

- 2nd Division (Blue), commanded by Flag Officer Farragut: the screw sloops Hartford, Brooklyn, and Richmond;

- 3rd Division (Red and Blue), commanded by Captain Henry H. Bell: six screw gunboats with the intent of passing by the two other divisions as they engaged the forts to reach the waiting Confederate gunboats.

Mortar Bombardment

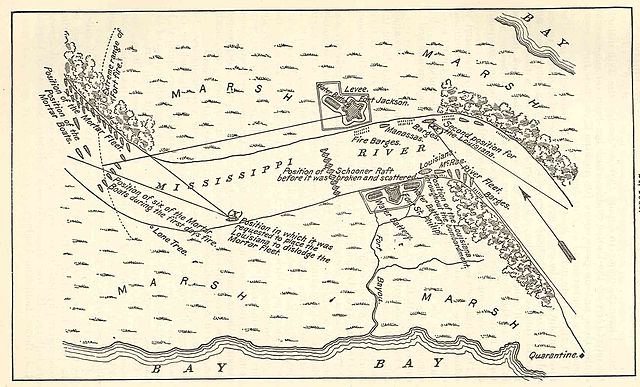

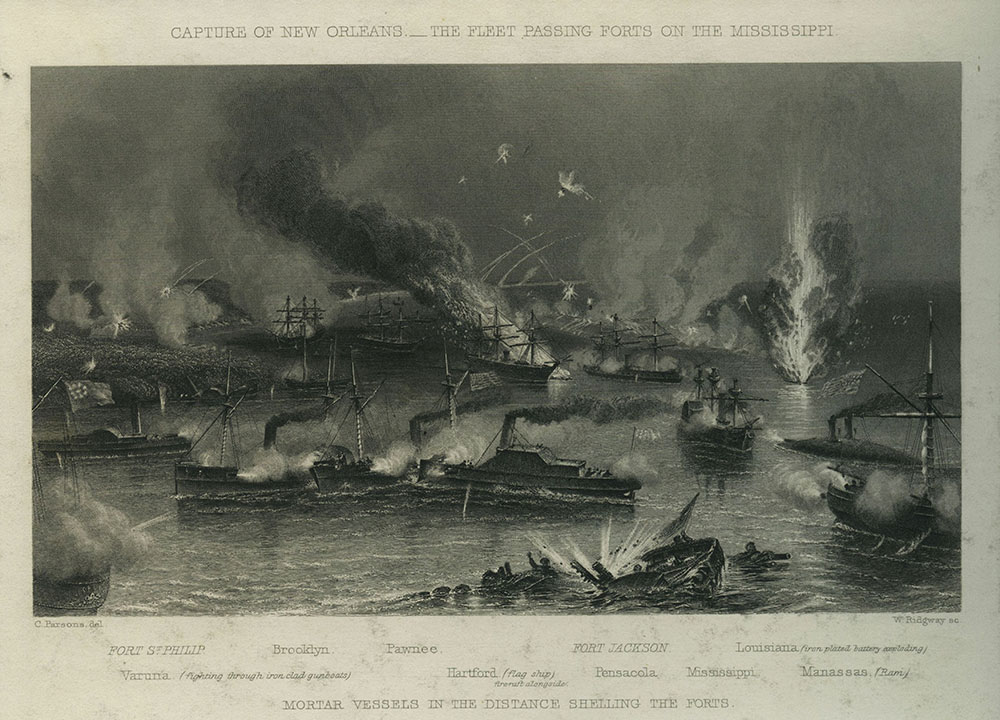

Farragut first needed to allow the mortar boats to do their work. Commander Porter’s mortar schooners began their bombardment of the Confederates at 9.00 a.m. on April 18. The schooners were camouflaged by trees (Porter had tree limbs placed atop their masts). More than 1,400 shells were lobbed into the forts during the bombardment’s first day.

1861 – 1870. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

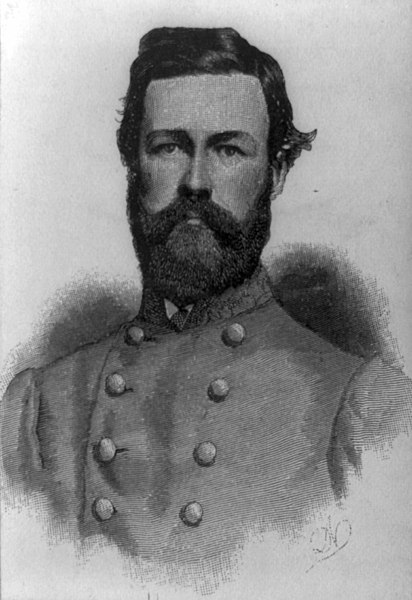

General Johnson K. Duncan reported that the constant shelling (a mortar round was fired every two minutes) caused minimal damage to the forts. Many shells exploded in the air or were buried in the mud surrounding the forts and within their parade fields. Nevertheless, barracks were burned, several artillery pieces were damaged, and Fort Jackson’s hot shot furnace was destroyed. Duncan reported only a few casualties; however, the roar of bursting shells did have a serious impact upon the garrison’s morale as the men huddled in the casemates.

By April 20, Farragut realized that the mortars were not having the desired impact upon the forts. He then ordered two gunboats, USS Itasca and Pinola, to move to break the chain across the river that evening. The Confederates noticed this work and fired flares and began to fire upon the chain-breaking crews. Despite the rockets lighting up the river, most of the cannon fire was inaccurate. But the chain-breakers were successful in making a huge gap in the chain.

Farragut was disappointed that Porter asked for more time to reduce the forts on April 23. The flag officer ordered his signal officer, B.S. Osbon, to go up Hartford’s mizzen mast to observe the effects of the shelling and to report by raising a white flag for a miss and a red one for a hit. This test proved that despite more than 7,500 shot and shells being fired at the forts, the bombardment had failed. Farragut decided that he would pass the forts early the next morning.

Passing the Forts

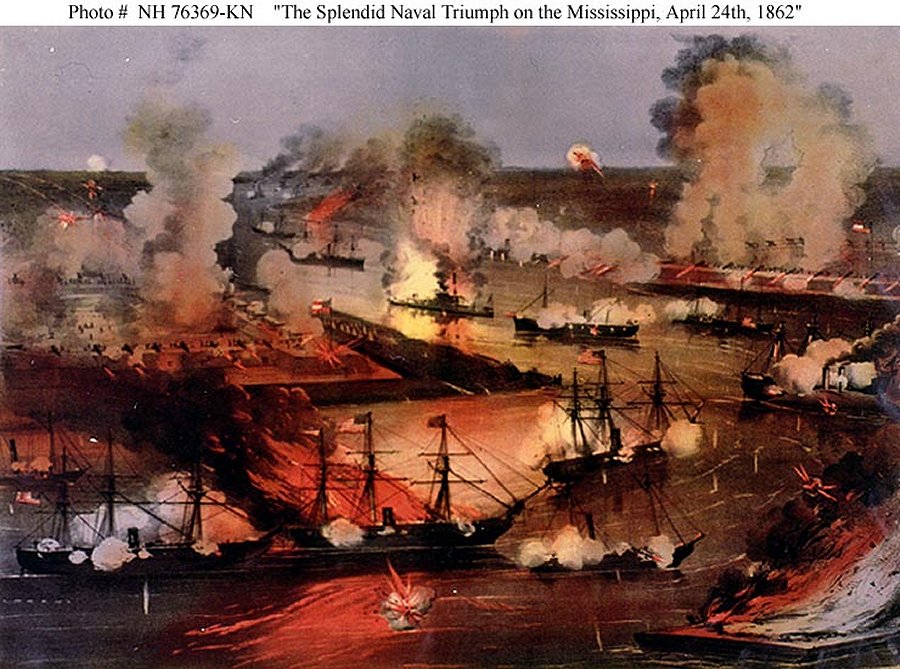

At 2:00 a.m. on April 24, 1862, Farragut’s flagship, Hartford, hoisted two red lanterns, the signal for the three divisions to get underway. By 3:30 a.m., Cayuga made through the gap in the chain. The Confederates did not notice the Federal ships were moving upriver until Pensacola made its run and the forts opened fire.

The battle quickly erupted in all its fury as Farragut remembered it was “as if the artillery of heaven were playing upon the earth.”

Confederate bonfires, rockets, and fire rafts illuminated the river. Gun smoke drifted across the forts which made it difficult to attain accurate fire. Nevertheless, when Richmond came within hailing distance of Fort Jackson, the fort’s cannon raked the sloop badly. This caused the warship to veer across the river where it was hit by heavy shot from Fort St. Philip. Other Union ships were struck several times by Confederate cannon fire. As shells decimated gun crews, hideous screams, groans, and shrieks filled the air.

CSS Louisiana now had an opportunity to prove its worth. The ironclad was under the direct command of Charles F. McIntosh; however, Flag Officer John K. Mitchell was also onboard the ironclad. Unfortunately, the ship could only bring its bow and starboard guns to bear. This was made even more difficult as the defective gun ports did not allow the crew to properly train the guns. Supposedly, three shots from Louisiana passed through Brooklyn. Union return fire simply bounced off the ironclad. Nevertheless, three men in exposed positions, including Commander McIntosh, were killed.

Destruction of Confederate Naval Forces

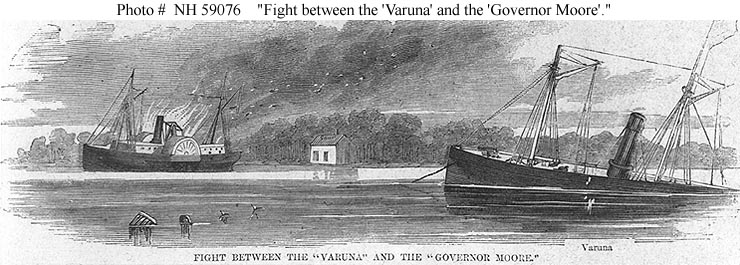

Hartford ran aground and a fire raft was pushed alongside the sloop. All seemed lost until the tug, CSS Mosher, was blasted by two shells and the raft floated away. CSS Governor Moore chased down USS Varuna, sinking it by ramming and gun fire; but was soon sunk itself. Other Confederate gunboats suffered similar fates.

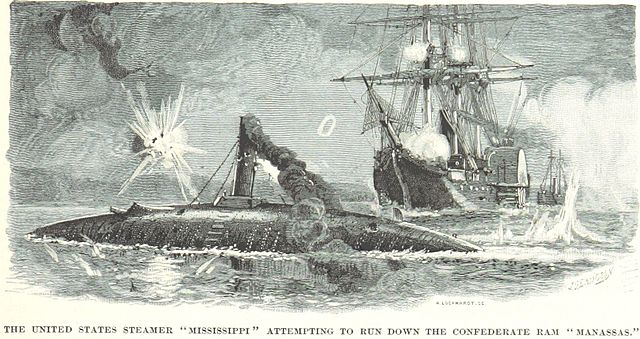

McRae was struck by grapeshot and canister by USS Iroquois and knocked out of action. The ironclad CSS Manassas tried to ram both the Cayuga and Pensacola. While it missed those warships, Lieutenant Alexander Warley, commander of the ironclad, took a course at Mississippi’s port paddle wheel which if successful, would have disabled the sloop.

Lieutenant George Dewey, later of Manila Bay fame, was at Mississippi’s wheel and maneuvered the paddler so adroitly that Manassas glanced off the frigate’s port quarter. Dewey looked down the side of his vessel as the ram steamed away. He saw that Manassas had ripped off planking, exposing the gleaming ends of copper bolts “cut as clean as if they were hair under a razor’s edge.”

Manassas then attempted to ram Hartford; but, missed. Warley was able to steer toward and strike Brooklyn as it passed through the chain barrier with such a fierce blow that the ram crushed the sloop’s inner and outer planking. Only the protected anchor chains saved the vessel; however, a shot from Manassas’s one gun tore through Brooklyn, lodging in the sandbags guarding its boilers. Manassas slid off the sloop and eventually attempted to steam back up the river; yet, its weak engines made this extremely difficult.

Farragut then hailed Mississippi Commander Melancton Smith “to run down that rascally ram.” Dewey quickly backed one wheel and drove forward the other, turned on its axis, and sped toward the ironclad.

Manassas was forced onto the riverbank where Mississippi riddled the ram, leaving it helpless; smoke poured out of fresh punctures which appeared to be portholes. The ironclad then drifted down river in flames, later exploding near Porter’s mortar flotilla.

Aftermath

The Confederates were unable to stop Farragut’s advance and he captured the defenseless New Orleans two days later. Farragut was proclaimed a hero by the Northern press for his victory. He would soon be promoted to rear admiral.

The Union capture of New Orleans was devastating to the Confederacy. The city was a critical industrial center and was a major key to the control of the Mississippi River. The loss of New Orleans helped to seal the fate of the Confederacy.

SOURCE: A History of Ironclads: The Power of Iron Over Wood, John V. Quarstein. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2006. Available in the Museum’s Web Shop: https://shop.marinersmuseum.org/a-history-of-ironclads.html