When the Civil War erupted, Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Russell Mallory knew that the South could only counter and defeat the larger US Navy if ironclads were employed. Mallory immediately ordered the construction of ironclads. The first project was the conversion of USS Merrimack into CSS Virginia at the Gosport Navy Yard, Portsmouth, Virginia. Mallory then ordered two ironclads laid down in New Orleans, and another two built in Memphis, Tennessee. These vessels could not be built fast enough to stem the Union’s advance against Confederate ports.

Ironclad Imagined

The urgent need for ironclads was recognized by New Orleans Commission Agent Captain John Stephenson who also served as secretary of the New Orleans Pilots’ Benevolent Association. Stephenson went to meet with President Jefferson Davis in Montgomery, Alabama, to ask for the use of a heavy tug, altering it to make it “comparatively safe against the heaviest guns afloat, and by preparing … bow in a peculiar manner … rendered them capable of sinking by collision the heaviest vessels ever built.” With Davis’s approval, Stevenson returned to New Orleans to build an ironclad privateer, quickly raising more than $100,000 in subscriptions.

Building a Hellish Machine

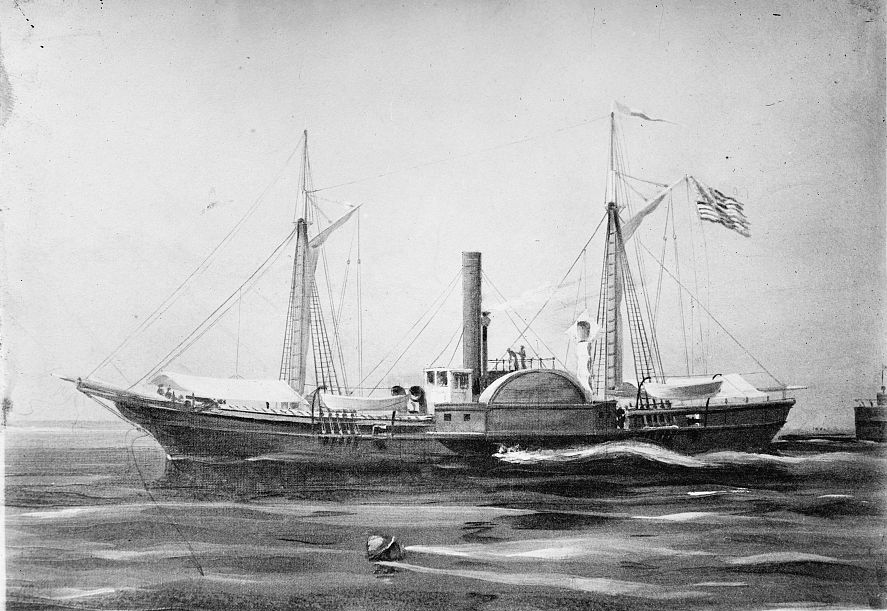

Fortunately for Stephenson, the privateer Ivy (later pressed into Confederate service) captured the tug Enoch Train off the coast of Louisiana. The powerful tug and its heavily reinforced bow seen service as icebreaker; and it was taken to a shipyard in Algiers, Louisiana, just across the river from New Orleans.

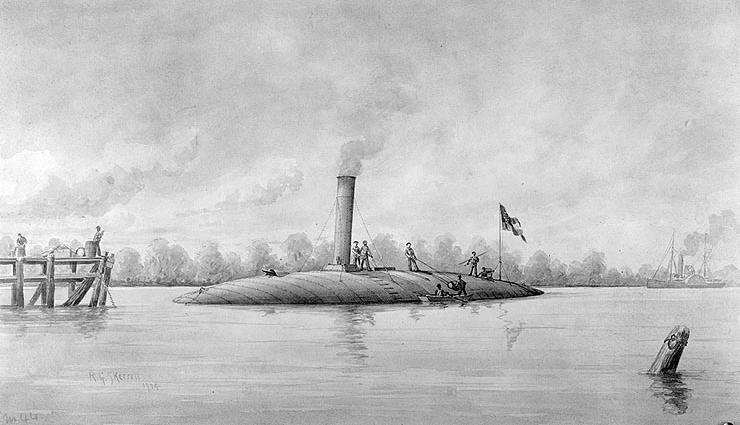

The vessel’s superstructure and masts were cut down and a convex shield was built over the main deck. The shield was built of 16 inches of oak and pine backing topped with 1.25-inch iron plate. The convex design was intended to cause enemy shot to glance off the side of the ironclad. The vessel’s bow was extended and strengthened to mount its cast-iron ram just below the waterline. The ironclad also featured a 64-pounder gun (later replaced by a 32-pounder), difficult and dangerous to reload; however, it could be aimed by pointing the ship at the intended target. The gun did have a cast-iron port shutter. Another defensive feature was a set of pumps installed to blow steam and scalding water across the ironclad’s shield to repel any boarders.

Once the conversion was completed, the ship was named Manassas, in honor of the Confederate victory on July 21, 1861. It was now 15 feet longer and its beam was widened by five feet. The draft had increased by four and a half feet. Manassas’s shield reached just six feet above the waterline. The engines needed overhaul; however, they were still able to push the ironclad forward 4 to 6 knots. Although it had been reported that Manassas had two stacks placed at a rakish angle, most observers noted that the ironclad only had one smokestack.

Something Much Like a Whale

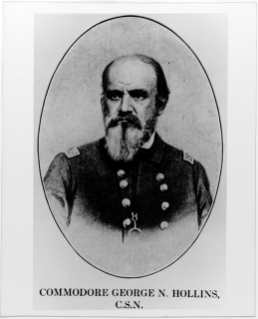

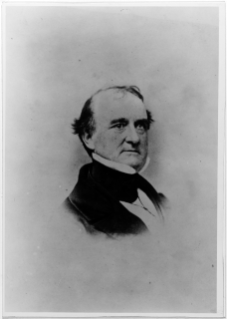

The ironclad Manassas was launched on September 12, 1861. Many observers called the ironclad a turtle or a long floating cigar; and it was the only ironclad on the Mississippi River. The commandant of the New Orleans Naval Station was Flag Officer George N. Hollins who had served under Stephen Decatur during the War of 1812 and the Second Barbary War. When the Civil War erupted, Hollins was the commander of USS Susquehanna. He gained great fame for his daring capture of the steamer St. Nicholas on June 29, 1861.

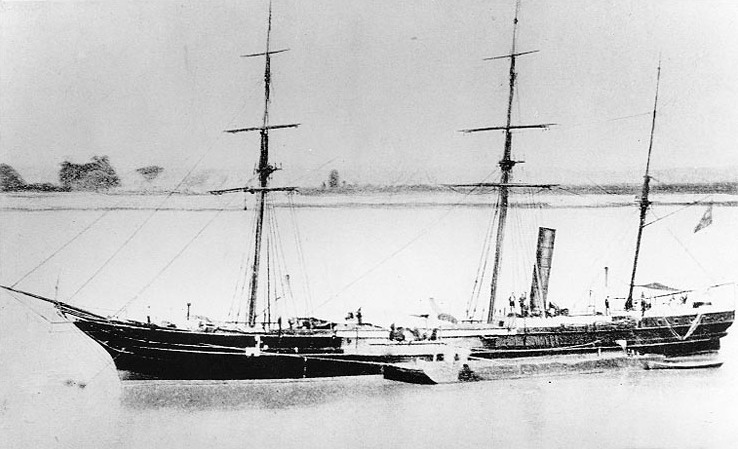

Later assigned to New Orleans, Hollins endeavored to create a fleet. He pressed every available vessel into service with his “mosquito fleet,” including CSS Calhoun (flagship), CSS Jackson, CSS Pickens. CSS Tuscarora, CSS Ivy, and CSS McRae.

Armed with eight guns, McRae was his most powerful ship. Formerly the Mexican warship Marquis de la Habana, it was captured as a pirate ship by USS Saratoga during the March 1860 Battle of Anton Lizardo. Hollins knew that he needed more powerful vessels if he was to stop the advance of the Union fleet toward New Orleans. Therefore, he cast his eyes lustfully upon the ironclad privateer Manassas.

Union Fleet Arrives

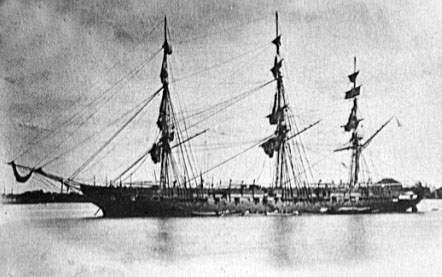

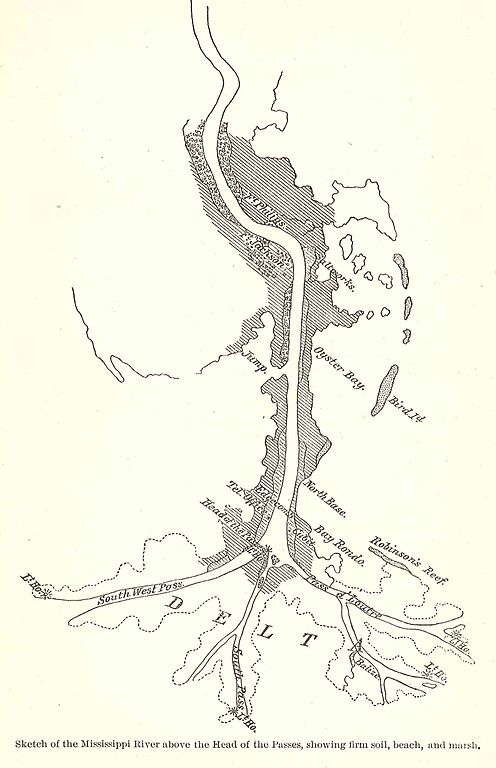

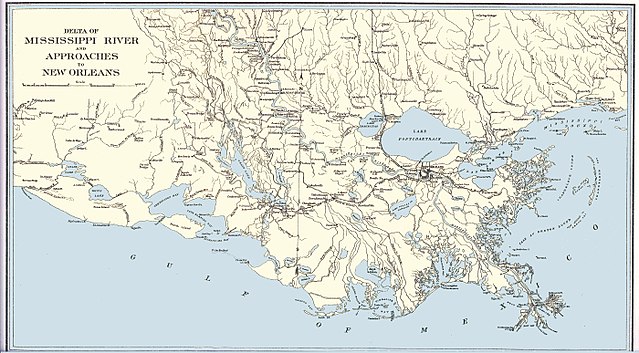

The first Union ship to arrive off the Mississippi Delta was the steam screw sloop USS Brooklyn on May 27, 1861. The sidewheeler USS Powhatan and the screw frigates Niagara and Minnesota soon arrived. These ships blocked the three outlets — Southwest Pass, South Pass, and Pass D’Loutre — for the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico.

The squadron was commanded by Captain William W. McKean. Once McKean received some reinforcements, he sent four warships to the Head of Passes where the outlets joined with the Mississippi River.

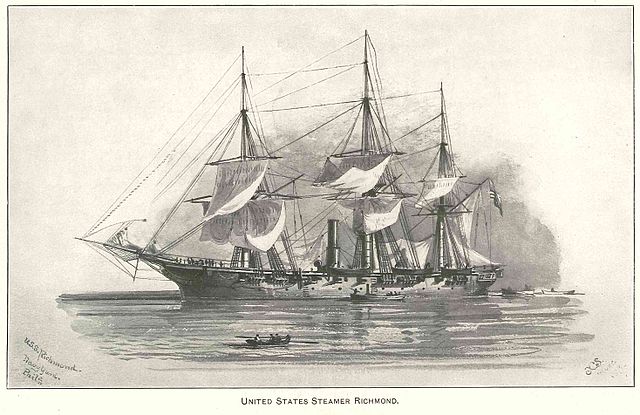

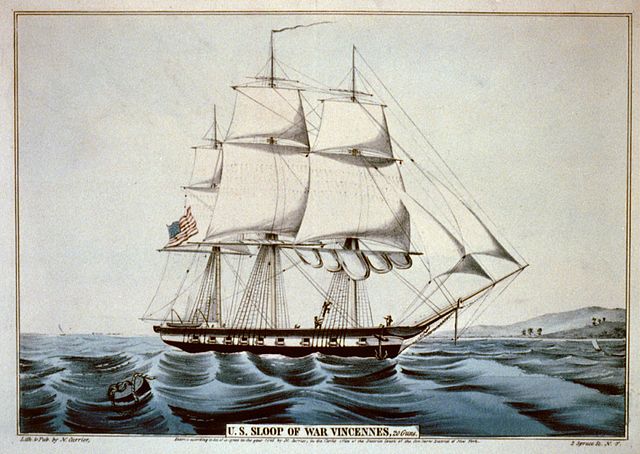

This flotilla consisted of four ships commanded by Captain John Pope of USS Richmond. He began assembling his command at the confluence of the passes in late September. The screw sloop Richmond was the most powerful of these ships. Mounting 14 IX-inch Dahlgren shell guns, this warship could blow Hollins’s mosquito fleet out of the water. Richmond was joined by the sailing sloops Vincennes (18 guns) and Preble (16 guns) as well as the sidewheeler gunboat USS Water Witch (10 guns).

Reconnaissance

When Flag Officer Hollins learned that Union ships had occupied the Head of Passes, he sent CSS Ivy to investigate on October 9, 1861. Ivy mounted two guns — an 8-inch shell gun and a 32-pounder banded rifle that outranged all of Pope’s guns. Ivy opened fire on the Union flotilla. The shells screaming overhead unnerved Pope, a veteran 45-year officer. He wished to abandon his position as he thought it was untenable. Yet Pope was ordered to stay in place. Despite his fears of an assault by a stronger force, Pope failed to set out picket boats, stations with flares, or any other precaution to warn him of the enemy’s approach.

Manassas is Seized

Hollins recognized the need to supplement his squadron with the ironclad Manassas. On October 10, he ordered Lieutenant Alexander Warley to take command of the vessel so that it could be added to the Confederate fleet. Despite protestations of the privateer’s owner and crew, Warley took the ship himself, armed with his cutlass and revolver. Warley was not impressed by what he had captured. The lieutenant called Manassas a “bug bear — no power, no speed, no strength of resistance and no armament.” Nevertheless, Warley quickly assembled a crew as Hollins planned to attack the Union fleet the next morning.

Confederate Attack

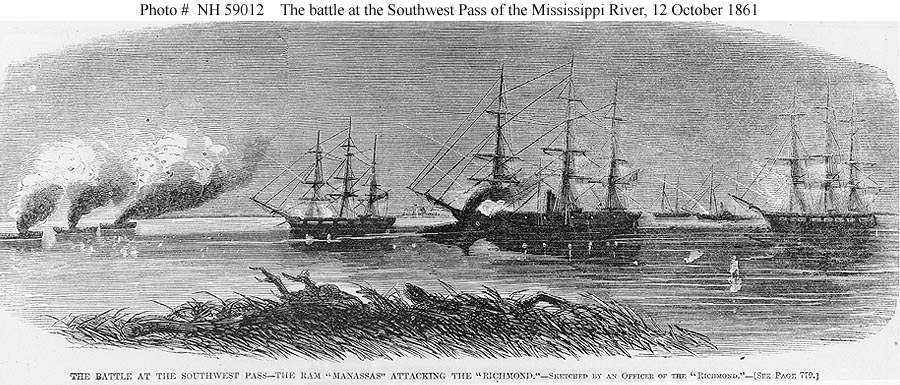

In the early morning of October 11, 1861, Hollins’s fleet headed down river. The conditions were perfect – “very dark, the moon had set, and the mist hanging low over the river” — for Hollins’s preemptive attack. The vessels were almost invisible in the eerie gloom. In the lead was Manassas, followed by three chained together fire rafts and the rest of the squadron. Once it had attacked an enemy vessel, Manassas was to launch three flares to announce that the fire rafts should be released.

About 4:40 a.m., Richmond was in the process of loading coal from the schooner Joseph H. Toone when a lookout from Preble shouted, “Ahoy! There is a boat coming down on your port bow.” The noise of the coaling probably masked the sound of this warning when suddenly, Manassas appeared out of the mist. When Manassas sighted Richmond, the firemen poured on coal and other combustibles to give the ram a burst of speed, enabling the ironclad to ram the Union sloop.

Although Richmond was damaged and sprang a major leak, the coaling schooner Toone absorbed much of the impact. The ram was momentarily trapped between Toone and Richmond. The lines parted, causing the coaling vessel to drift away, enabling Manassas to escape. The ironclad was severely damaged when it hit Richmond. The impact caused the ram to break off, causing a leak. The hull buckled, resulting in yet another leak, and one of the engines was knocked off its mounting. To make matters worse, the ram’s smokestack was knocked down causing choking fumes to engulf the Confederate ship’s interior.

In all this confusion, Richmond and Preble fired at the ram; but, because of the ironclad’s low profile they overshot Manassas. As Manassas struggled to make its way upstream, the crew began to set off the flares, indicating that the fire rafts should be released. The scene almost became comical as one of the rockets was accidentally released inside Manassas, ricocheting about the interior. Upon seeing the other rockets burst in the air, the fire rafts were released and floated down the river toward the Union flotilla.

Pope’s Run

Captain Pope panicked when he saw the fire rafts floating towards him. He ordered his ships to slip their cables and retreat down the Southwest Pass. Water Witch was the last to leave the Head of Passes. When this sidewheeler reached the bar at the mouth of the river, it witnessed Richmond and Vincennes running aground. Only Preble had reached the safety of the Gulf of Mexico.

At daylight, Hollins’s squadron approached the Union vessels and began shelling the grounded, hapless warships. The commander of Vincennes misread a signal from Captain Pope and ordered the ship to be abandoned. As the sailing sloop’s crew reached Richmond, they learned that the order was to read “Get Underway.” So they returned to their ship and cut the fuse leading to the magazine. Finally, these Union ships were freed by the changing tide and crossed the bar into the Gulf.

A Hero’s Acclaim

Flag Officer Hollins missed an opportunity to capture Vincennes. He broke off action as his ships were low on ammunition and fuel. He returned to Fort Jackson towing Manassas and the captured coaling schooner. Lauded throughout the South, even though it suffered more damage than its victim, Manassas was the first ironclad attack of the Civil War. The result? Ram Fever was born!

A Most Ridiculous Affair

Captain Pope reported, “Everyone is in dread of that infernal ram.” Squadron commander Flag Officer McKean reported, “the more I hear and learn of the facts the more disgraceful it does appear.” The ridiculous Union actions during the engagement resulted in Capt. John Pope’s resignation for “health reasons.” Shortly thereafter, Flag Officer David Glasgow Farragut organized the West Gulf Blockading Squadron and was detailed to capture New Orleans.

SOURCE: A History of Ironclads: The Power of Iron Over Wood, John V. Quarstein. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2006. Available in the Museum’s Web Shop: https://shop.marinersmuseum.org/a-history-of-ironclads.html