Major General John Bankhead Magruder arrived in Texas in late October 1862 and immediately sought to regain the laurels he had earned on the Virginia Peninsula. Galveston, Texas’s major port, had been conquered by Union naval forces earlier the same month. Consequently, Magruder decided to organize a land sea operation to break the Union grip on Galveston thereby reopening this port to Confederate blockade runners. Galveston would remain in Confederate hands until the war’s conclusion.

Welcome to Galveston

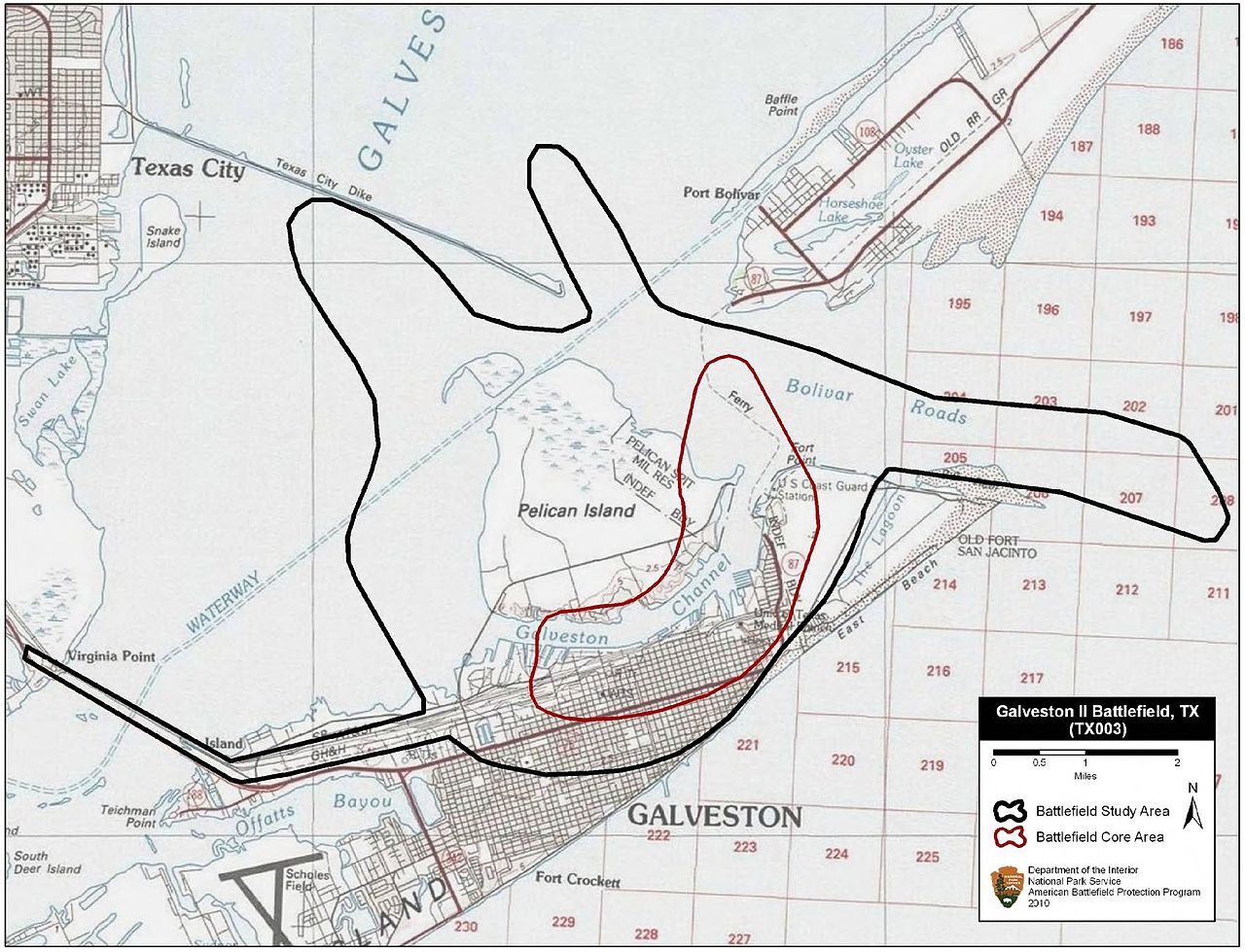

Galveston, Texas, was the state’s primary cotton port, exporting 194,000 bales in 1860. It was also the largest city in the Lone Star State with about 6,000 white and 1,200 enslaved people as residents. One observer estimated that Galveston’s commerce was increasing at almost a rate of 50 percent a year. In 1860, Galveston was a city on the barrier island known as Galveston Island which along with the Bolivar Peninsula formed Galveston Bay. Galveston was connected to the mainland by the Galveston, Houston and Henderson Railroad’s trestle bridge.[1]

Despite its commercial value, Galveston was virtually defenseless when the war erupted. Colonel John S. “Rip” Ford had captured 12 cannons during his Rio Grande Valley Campaign. Sidney Sherman, a veteran of the 1836 Battle of San Jacinto, endeavored to create fortifications. Another six guns were sent to enhance the city’s defenses from Fort Clark in West Texas. Yet so much more was required to protect the port from the US Navy. Captain Walter H. Stevens requested at least five VIII-inch shell guns and five companies of artillerists. He also helped organize the forts at Pelican Spit and Fort Point. These defensive works were inadequate for the needs at hand.[2]

A City Threatened

The war quickly came to Galveston. On July 2, 1861, the blockader USS South Carolina arrived off the entrance to Galveston Bay. It was built as a passenger ship by Harrison Loring of Boston, Massachusetts, and was acquired by the navy immediately after the war’s outbreak. This iron-hulled, screw steamer was armed with four VIII-inch shell guns and one 32-pounder. While serving off the entrance to Galveston Bay, the South Carolina, commanded by Commander James Alden, captured 11 Confederate blockade runners from July 4-12, 1861.[3]

The arrival of the Union blockader prompted greater enlistments in the Third Battalion Texas Artillery commanded by US Naval Academy graduate Major Joseph J. Cook. A total of seven companies were mustered including the Houston Artillery and the Davis Guards to man the defenses defending Galveston. A group of local citizens went to Richmond, Virginia, and eventually met with Major General Josiah Gorgas. Eventually, they secured several heavy cannons for shipment to Galveston.[4]

District of Texas

Brigadier General Paul O. Hebert was named as commander of the District of Texas in mid-September 1861. Hebert was a native of Louisiana. He graduated first in his class at Jefferson College and first in the Class of 1840, USMA. Named chief engineer of the State of Louisiana, he resigned to serve as lieutenant colonel of the US 14th Infantry during the Mexican War. He was brevetted colonel during General Winfield Scott’s capture of Mexico City. After the war, Hebert was elected governor, serving from 1853 to 1856. During his term he founded what would eventually be Louisiana State University. He also improved railroad systems in the state.

When Louisiana left the Union, Hebert was named brigadier general and was soon assigned as commander of the District of Texas.[5] Hebert was immediately confronted with the serious problem of defending the Texas coastline. He wrote Secretary of War Judah Benjamin, “I regret to say that I find this coast in almost defensive state, and in the almost certain want of proper works and armaments, the task of defending successfully at any point against an attack of any magnitude amounts to a military impossibility.”[6]

Hebert’s fear of attack materialized on May 17, 1861. The district commander had sent most of his troops to support Earl Van Doren’s army in Arkansas. Cook was then promoted to colonel and his battalion had expanded. His unit became the First Texas Heavy Artillery. Cook was totally unable to stop Captain Henry Eagle of the USS Santee from demanding Galveston’s surrender. A 44-gun sailing frigate, Santee had been able to capture or damage four ships off Galveston Bay including the Royal Yacht.[7] Colonel Cook spiked his guns on Pelican Island and made efforts to remove all the heavy guns from Galveston to the mainland. Eagle’s bluff could not be enforced as he did not have any troops with him.[8]

Farragut Plans Another Conquest

Once Rear Admiral David Glasgow Farragut had completed his operations against New Orleans and Vicksburg, he cast his eyes on the Texas coast. He knew that Galveston was poorly defended and sent Commander William Bainbridge Renshaw to capture that port city.

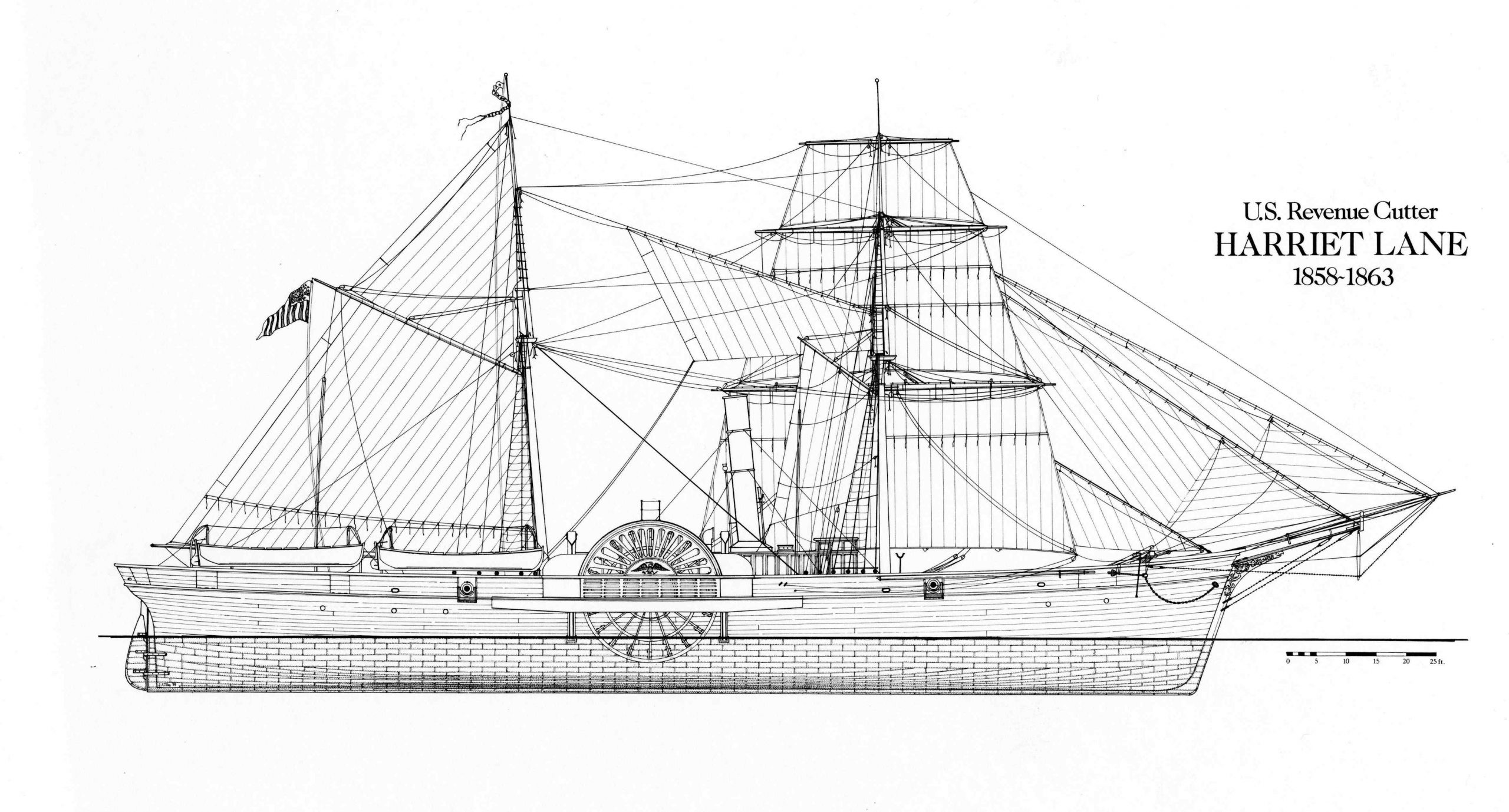

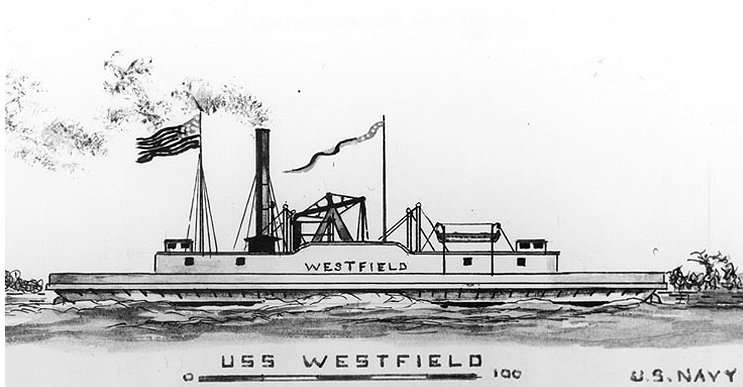

Renshaw, who had been in the US Navy since 1831, had organized a powerful squadron to do this work — Harriet Lane, Owasco, Clifton, Sachem, and Westfield; the tender John F. Carr; transports Cavello and Elias Pike; and the pilot schooner LeCompte.

The sidewheeler Harriet Lane was built for the US Revenue Cutter Service by Webb of New York and was named in honor of President James Buchanan’s niece. The cutter was armed with one IX- and two VIII-inch shell guns, two 24-pounder brass howitzers, and one 4-inch gun.

Another sidewheeler, Clifton, was formerly a New York ferryboat. The vessel had an iron-strapped hull and was armed with two IX-inch Dahlgrens and four 32-pounders. The Owasco was an Unadilla-class gunboat, commissioned on January 23. The gunboat was armed with one XI-inch Dahlgren, two 24-pounder howitzers, and one 20-pounder rifle. Another steam screw gunboat, Sachem, was armed with one 20-pounder rifle and four 32-pounders. Renshaw’s flagship, USS Westfield, was a sidewheeler armed with one 100- pounder rifle, one IX-inch Dahlgren, and four VIII-inch shell guns.[9]

Renshaw entered Galveston Harbor on October 4, 1862. General Hebert thought that it would be folly to attempt resistance and retreated. Five days later, the Federals occupied Galveston. Renshaw believed that he desperately needed troops to maintain effective control of the port and without them he might be forced to abandon the harbor. Farragut advised him that troops would soon be sent to garrison the city. Under no circumstances was the navy to leave Galveston.[10] Elements of the 42nd Massachusetts, under the command of Colonel Isaac S. Burrell, did not arrive until December 24 and were positioned on Kuhn’s Wharf.

Renshaw believed he would not be safe until the rest of the regiment arrived. The Unionists expected an attack at any time; yet were unable to organize a viable defensive position. The trestle bridge was not burned connecting Galveston with the mainland, giving the Confederates possible access to the city. Also, many Federals thought their naval superiority would provide adequate defense for the harbor area. Unfortunately, they did not know about the buildup of nearby Confederate army cottonclads.[11]

‘The Master of Ruses and Strategy’ Arrives with Great Flourish

Hebert’s dismal performance prompted his removal as commander of the District of Texas. He had not been popular with the Texans anyway. Thomas North noted: “Everyone became tired and disgusted with the General and his policy. He was too much of a military coxcomb to suit the ideas and ways of a pioneer country; besides, he was suspected of cowardice.”[12].

When the Texans learned of the appointment of Major General John Bankhead Magruder as commander of the District of Texas, they knew that he was exactly the man needed to command the state. John S. Ford thought that Magruder’s arrival “was equal to the addition of 50,000 men to the forces of Texas.”[13]

John Bankhead Magruder was born in Port Royal, Virginia, and was a member of the first class at the University of Virginia. The following year, he received an appointment to the USMA and graduated with the Class of 1830. He saw service in the Second Seminole War. Promotions were slow for Magruder until his first rise to fame during the Mexican War. Captain Magruder commanded Company I, 1st US Artillery during General Winfield Scott’s capture of Mexico City. His commander, Colonel William S. Harney, reported, “Captain Magruder’s gallantry was conspicuously displayed on several occasions.” [14] Magruder was wounded twice during the capture of Mexico City. He was brevetted to lieutenant colonel and received a gold sword from the Commonwealth of Virginia for his distinguished actions. After the Mexican War Magruder served in California, Texas, and Rhode Island. When he commanded Fort Adams, Newport, RI, he “enjoyed a fine field for exercising his high social qualities and fondness for military display.” Magruder’s “princely hospitality “[15] achieved him little rewards. Plagued by his heavy drinking, “Prince John,” as he was often called, his army career seemed destined to go nowhere. When the Civil War began, Magruder was assigned to command the Army of the Peninsula. He achieved victory during the June 10, 1861 Battle of Big Bethel. Magruder was accorded most of the glory for the victory. “He’s the hero for our times,” one ballad proclaimed, “the furious fighting Johnny B. Magruder.”[16]

Magruder went on to achieve even greater fame during the Peninsula Campaign when his 13,000-strong army blocked Major General George B. McClellan’s 121,000-man Army of the Potomac at Yorktown. Magruder’s bluff along the Warwick-Yorktown Line slowed McClellan for almost a month, earning him the title “Master of Ruses and Strategy.” He moved his troops back and forth along his defensive line to present an illusion of greater strength. “It was a wonderful thing,” recorded diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut, “how he played his ten thousand before McClellan like fireflies and utterly deluded him.” [17] Unfortunately, Magruder performed poorly during the Seven Days Battle. He was accused of drunkenness during the July 1, 1862 Battle of Malvern Hill; however, the charges proved to be false. It appeared that Magruder worked better holding an independent command. Accordingly, Magruder went west to retrieve his fame.

A Plan is Forged

Magruder arrived in Texas on November 29, 1862. He was met with great fanfare and was lauded by the citizens of Houston. Fame seemed to fall upon him naturally, and in every fashion Magruder strove to live up to the honor bestowed upon him. He was a vigorous 52 years old, tall, erect, and handsome. Always perfectly uniformed, he appeared everywhere at a gallop, talking incessantly despite his unusual lisp. His impressive nature, dramatic flair, and strategic sense would soon bring a victory in the fight to regain Texas’s primary port. Galveston simply had to be taken to open the door to blockade runners; thereby, reopening the state’s economy.

Magruder knew that he had to strike quickly against Galveston if he were to have any measure of success. Even though the Union had a complete advantage in manpower, firepower, and naval strength, Magruder began to develop plans for an offensive. The general and his staff surveyed the Union positions on Kuhn’s Wharf and the Federal flotilla’s anchorages. Prince John then formulated a two-prong attack. By land he sought to position his troops at night to facilitate an assault against Kuhn’s Wharf in the early morning of December 31, 1862. The plan entailed that shortly after the land attack commenced, a Confederate naval force would then strike the Union warships. [18]

The amphibious assault was probably the most daring as the Confederates had no real warships in Texas waters. The Bayou City and Neptune were paddler packet boats. They were supported by two tenders, John F. Carr and Lucy Gwinn, under the overall command of Major Leon Smith. The Bayou City was built in Jeffersonville, Indiana, and was commanded by Captain Henry S. Lubbock, brother of Texas governor Francis Lubbock. A rifled 32-pounder shell gun was placed near the ship’s bow, commanded by Captain A. R. Weir of the 1st Texas Heavy Artillery.[19] Also,150 volunteer sharpshooters were on board. These men were armed with Enfield rifles that Magruder had brought with him from Richmond.[20]

The Bayou City was also fitted with a ram as well as a corvus (a Roman boarding device used during the Punic Wars). It was a bridge about four feet wide and 36 feet long with a parapet on both sides. It was placed in the ship’s prow where a system of pulleys allowed the bridge to be raised or lowered. There was a small, heavy spike shaped like a bird’s beak on the underside of the device. This was designed to pierce and anchor the corvus into an enemy’s deck when the bridge was lowered.[21]

The other packet boat, Neptune, was commanded by Captain W. H. Sangster. The vessel was armed by two 24-pounder howitzers commanded by Lieutenant Levi Charles Harby. A member of Galveston’s Jewish community, he was 70 years old at the time of the engagement. Harby had formerly been a captain in the US Revenue Cutter Service. About 150 volunteers from Colonel Bagby’s 7th Texas Cavalry were stationed on board as sharpshooters.

Both the Bayou City and Neptune were called cottonclads. Bales of cotton were stacked to protect the machinery and sharpshooters from shot and shell. When one nervous sharpshooter asked Harby whether or not the cotton bales would protect them, he replied: “None, whatever, not even against grapeshot; our only chance is to get alongside before they hit us.” Obviously, the bales just gave the appearance of protection. [22]

The Battle is Joined

While the naval attack squadron was organized at Harrisburg, Texas, Magruder prepared his men for the main assault. First, Captain Sidney T. Fontaine’s command moved three siege guns to Fort Point at the mouth of the bay. This position was planned to block the Union’s fleet escape route. Lieutenant Colonel John Manly was in command of the mainland Virginia Point batteries. Major Edward Von Harten was in command of the artillery that had to be moved across the railroad bridge under cover of darkness. This was supported by 1,000 men under the command of Brigadier General William R. Scurry. Scurry had served as the commander of the 14th Texas Mounted Rifles at the Battle of Glorieta Pass on September 12, 1862, during the Confederate invasion of New Mexico. He was promoted brigadier general on September 14, 1862, and was assigned, with his brigade, to Galveston.[23]

Meanwhile, Magruder had gone to Morgan’s Wharf to cheer on Smith’s squadron. He advised Leon Smith to prepare to attack; however, not until he heard the signal gun from Galveston. Then he should steam down the bay to strike the Union fleet. The citizenry smelled victory in the air, and it was quite a gala scene with flags flying, bands playing, and crowds cheering. As Magruder left by train to lead his troops into battle, Prince John shouted from the train a hearty salutation: “The Rangers of the Prairie send greetings to the Rangers of the Sea.” [24]

Magruder returned to Virginia Point and immediately pressed his command to cross over to the island. Planks were laid to provide proper footing on the trestle bridge to drag 14 field guns and an VIII-Dahlgren mounted on a flat car. The mules became so unruly that it disrupted the entire advance. Men from Colonel Henry M. Elmore’s 20th Texas Infantry replaced the mules as they pushed and pulled the cannons across the railroad bridge and placed them in Magruder’s designed positions to shell Kuhn’s Wharf and the Union flotilla. [25] One of the soldiers serving in Co. K, 20th Texas Infantry, known as Col. Elmore’s regiment, was the young musician Private Carl Heinrich Ludwig Gerloff. Gerloff later complained “that it was the hardest task of his life moving the cannons through the sand.” [26]

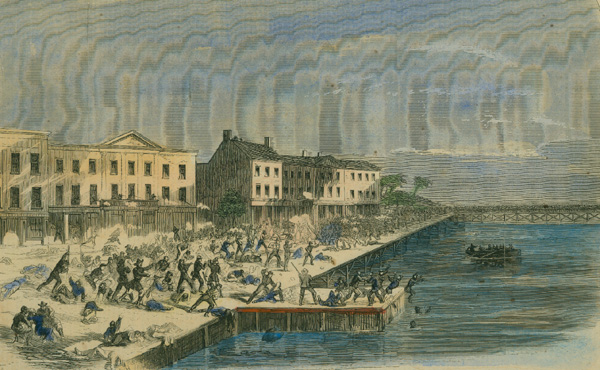

Even though the Confederates had muffled their cannon wheels as they moved through the streets of Galveston, Federal pickets heard the advancing Texans. The Massachusetts troops all fell back to the head of 18th Street which culminated at Kuhn’s Wharf. The Federals pulled up some of the planking to limit access to the pier and used them to strengthen their barricades. Just before 5:00 a.m. on the morning of January 1, 1863, Magruder shouted, “Boys, now we will give them hell,” and fired the first cannon shot toward the Union ships. He then rode off to his headquarters yelling, “Boys, I have done my part as a private. I will go and attend to that of a general.”[27]

The artillery battle between the shore batteries and the Federal fleet soon became one of most terrific on record. The Owasco and Harriet Lane poured “an appalling rain of iron” into the Confederate positions. It was quite the unequal duel between Confederate field cannon and the Union ships’ IX- and XI-inch Dahlgren shell guns. Some Confederates fled their position. Commander Renshaw wanted to bring all his naval guns to bear on the Texans. Nevertheless, the Westfield ran aground on Pelican Spit and the Clifton stopped to help the flagship off the shoal. Some Confederates were forced to abandon their gun position because the Federal fire was so hot.[28]

During this shelling, Col. Joseph Cook led 500 volunteers in a predawn attack through the cold, chest-high waters to capture the wharf. The 50 scaling ladders they carried with them were too short. Despite the support of Confederate sharpshooters and cannon, the Harriet Lane plunged shell and grapeshot into the Texans. Cook ordered his men to fall back. Near daybreak, Magruder called his men back from the wharf area. Just before these orders could be executed, the Bayou City and Neptune appeared out of the early morning’s gloom laden with gun smoke. [29]

Victory

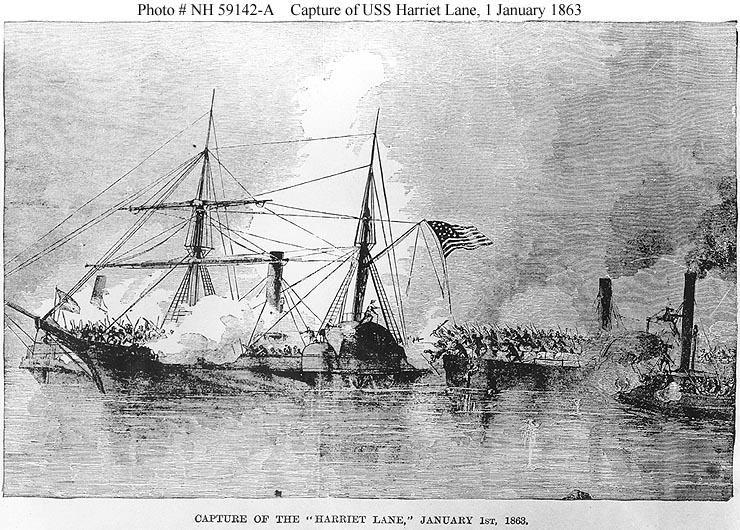

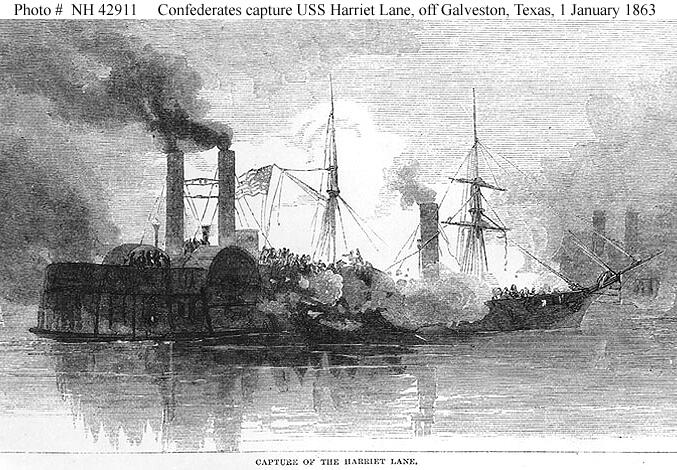

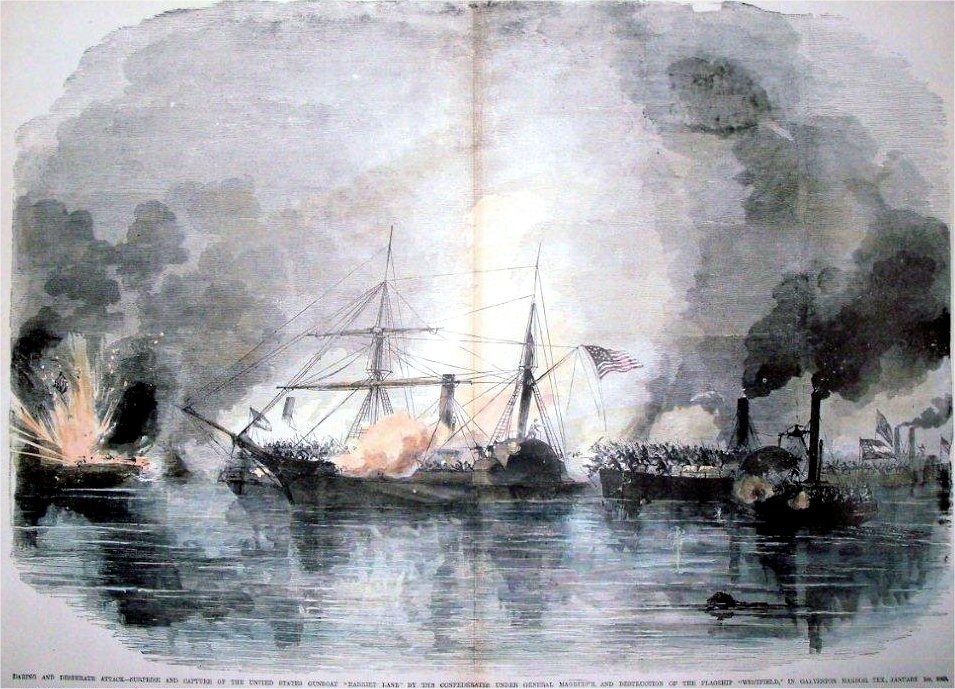

The Bayou City fired its 32-pounder rifle into the Harriet Lane causing serious damage to the Union gunboat. When the third shot was readied to fire, Weir called out, “ Well, here goes for a New Year’s present!”; the gun exploded killing Weir and several others. Undaunted, Smith drove the Bayou City toward the enemy’s gunboat; but missed, causing some damage to the cottonclad.

In the meantime, the Neptune headed toward the Harriet Lane and rammed the steamer. This caused more damage to the Neptune as the warship began to take on water when a shell from the Union warship blew a hole in the cottonclad’s hull. The Neptune immediately started to sink. Fortunately, it was only in eight feet of water, so Lt. Harby kept his howitzers and sharpshooters firing in a rapid fashion. This caused the Harriet Lane to maintain its attention on the pesky little cottonclad. [30]

While the Neptune engaged the Federal gunboat, the Bayou City had rounded-to and rushed toward the Harriet Lane with a full head of steam. Colonel Tom Green’s sharpshooters forced many of the gunboat’s seaman below deck.

Then the Bayou City struck the Harriet Lane with full force aft of the port wheel which embedded the cottonclad’s ram deep into the Harriet Lane thereby locking the two ships together. The corvus was lowered as the Confederates poured onto the hapless gunboat. Leon Smith’s boarding party dove into a deadly close range firefight. Federal resistance ended when Wainwright, already wounded twice, was shot through the head by Leon Smith. The executive officer, Lieutenant Edward Lea, USNA 1855, was mortally wounded so the rest of the Harriet Lane’s officers and crew surrendered.[31]

As the Confederates began taking the wounded off the Harriet Lane, one of Magruder’s friends from West Point and serving then as an aide to Prince John, Major Albert M. Lea, found his mortally wounded son, Lt. Edward Lea, dying on the deck. As the major comforted his son, the young man told his father, “You have seen that I have done my duty to the last and have died fighting for my country. Tell them at home that I love them.’[32]

The Owasco backed away from the action as it was apparent the gunboat could not save the Harriet Lane. As the Federal commanders considered their next action, Capt. Lubbock went out to the Clifton and demanded the surrender of the Union squadron and a three-hour truce was agreed upon. Lubbock returned to the wharf and Gen. Scurry demanded unconditional surrender of Colonel Isaac Burnett’s command. Burrell had no over choice but to agree to the terms.[33]

Commander Renshaw had different thoughts about the truce and possible surrender of his squadron. He knew that his ship could not be saved. He believed that he should ‘sink before surrender’ and made plans to scuttle the Westfield. The crew were evacuated and, at 10:00 a.m., Renshaw poured turpentine all over the magazine and set the fuse himself. The magazine exploded prematurely killing Renshaw and his ship. The scene was horrific as the Union gunboat “was seen to part or burst forward … and when the smoke cleared away there was no sign of life about her. Forward she was blown into fragments down to the water.”[34]

Commander Richard Law now assumed command of the remnants of the squadron. He refused to follow the truce agreement and escaped from the bay with the remaining ships. Major Leon Smith organized 150 volunteers aboard the tender John F. Carr; however, he was unable to catch up to the retreating Federal fleet.

The Battle of Galveston was a stunning victory for the Confederates. They had recaptured the port city, captured the gunboat Harriet Lane, removed the guns from the wrecked Westfield, captured the barks Elias Pike and Cavallo, containing 700 tons of coal and 600 barrels of Irish potatoes, and a pilot schooner. The Union lost two warships and suffered 420 casualties. In turn, the Confederates lost 26 killed and 117 wounded. While the Confederates proclaimed the blockade was broken, Federals ships were soon back on station. Nevertheless, Galveston remained a blockade runner’s haven until the end of the war.[35]

Prince John Redeemed

Even though Magruder had been highly lauded for his service on the Virginia Peninsula, he had lost his hero status for his failures during the Battle of Malvern Hill. His victory on January 1, 1863, gave him even greater laurels. Prince John was once again a hero for all time. As Confederate president Jefferson Davis wrote the general: “I am much gratified at the receipt of your letter of January 6th conveying to me the details of your brilliant exploit in the capture of Galveston and the vessels in the harbor. The boldness of the conception and the daring and the skill of its execution were crowned by results substantial as well as splendid. Your success has been a heavy blow to the enemy’s hopes and I trust will be vigorously and effectively followed up. … The congratulations I tender to you and your brave army are felt by the whole country. I trust that your achievement is but the precursor of a series of successes, which may redound to the glory and honor of yourself and our country.” [36]

ENDNOTES

1 autarch.tamu.edu/PROJECTS/denbigh/galv01.htm

2 Alywn Barr, THE BATTLE OF GALVESTON: AN ADDRESS DELIVERED BY MR. ALWYN BARR OF AUSTIN AT THE MEETING OF THE TEXAS CIVIL WAR CENTENNIAL COMMISSION IN GALVESTON, JANUARY 4,1863.

3 Paul H. Silverstone, CIVIL WAR NAVIES: 1855-1883, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press,2001, p. 59.

4 Barr

5 Ezra Warner, GENERAL IN GRAY: LIVES OF CONFEDERATE COMMANDERS, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959, p. 131.

6 WAR OF THE REBELLION: A COMPILATION OF THE OFFICIAL RECORDS OF THE UNION AND CONFEDERATE ARMIES (Washington: US Government Printing Office, 1901), (hereinafter cited as OR), ser.1, 4: 112.

7 Silverstone, p. 97.

8 Barr

9 Silverstone, pp. 30-33, 69, 72, 77, and 139.

10 OFFICIAL RECORDS OF THE UNION AND CONFEDERATE NAVIES IN THE WAR OF REBELLION, (Washington: US Government Printing Office, 1927) ser. I, 19:319, 1927.

11 J. Thomas Scharf, HISTORY OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES: FROM ITS ORGANIZATION TO THE SURRENDER OF ITS LAST VESSEL, (New York: Gramercy Books, 1996), p. 505.

12 Thomas North, FIVE YEARS IN TEXAS; OR, WHAT YOU DID NOT HEAR DURING THE WAR FROM JANUARY 1861 TO JANUARY 1866. A NARRATIVE OF HIS TRAVELS, EXPERIENCES, AND OBSERVATIONS IN TEXAS AND MEXICO (Cincinnati: Elm Street Printing Co., 1871), p.108.

13 John Salmon Ford, RIP FORD’S TEXAS, ed. Stephen B. Oates, (Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 1963), p. 343.

14 William L. Haskins, HISTORY OF THE FIRST REGIMENT OF ARTILLERY FROM ITS ORGANIZATION IN 1821, TO 1 JANUARY 1875 (Portland, Maine, privately printed), p.321.

15 Armistead Long, “Memoir of General John Bankhead Magruder,” SOUTHERN HISTORICAL SOCIETY PAPERS, 12 (1884), pp. 105-106.

16 Patricia Faust, ed, HISTORICAL TIMES ILLUSTRATED ENCYCLOPEDIA,(New York: Harper & Row, 1988) p. 468.

17 C. Vann Woodward, ed. MARY CHESNUT’S CIVIL WAR (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981), p. 401.

18 Thomas M.Settles, JOHN BANKHEAD MAGRUDER: A MILITARY REAPPRAISAL, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009) p.246 and Barr

19 Silverstone, p. 175 and Barr.

20 OR, ser.1, vol. 15: 901.

21 Herman Tommo Wallinga, THE BOARDING-BRIDGE OF THE ROMANS, (Groningen, Germany: J.B. Wolters, 1956), p. 12.

22 Robert N.Rosen, THE JEWISH CONFEDERATES (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000), p. 141.

23 Mark M, Boatner III, THE CIVIL WAR DICTIONARY (New York: Vintage Books, 1991) p.729

24 Barr

25 Ibid.

26 Gerloff Family Papers.

27 Scharf, p. 506.

28 Ibid, pp. 506-507 and Barr

29 Scharf, p. 507 and Settle, p. 247.

30 Rosen, p. 141 and Scharf, p. 507.

31 Duncan Howard, ed. ‘When the War Stood Still Galveston,” THE TEXAS MASON, Spring 1994, p.18 and Scharf, p. 507

32 GALVESTON NEWS

33 Barr

34 Scharf, p. 509

35 Ibid.

36 Ibid, pp. 511-512.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

autarch.tamu/PROJECTS/denbigh/gslv01.htm

Barr, Alwyn. THE BATTLE OF GALVESTON. An Address Delivered By Mr. Alwyn Barr of Austin At The Meeting of The Texas Civil War Centennial Commission In Galveston, January 4, 1963.

Boatner, Mark M. THE CIVIL WAR DICTIONARY. New York: McKay, 1988.

Casdorph, Paul D. PRINCE JOHN MAGRUDER: HIS LIFE AND CAMPAIGNS. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1996

Faust, Patricia, ed. HISTORICAL TIMES ILLUSTRATED ENCYCLOPEDIA. New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

Ford, John Salmon. RIP FORD’S TEXAS. Edited by Stephen B. Oates. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1963.

GERLOFF FAMILY PAPERS.

Haskins, William. HISTORY OF THE FIRST REGIMENT OF ARTILLERY FROM ITS ORGANIZATION IN 1821, TO 1 JANUARY 1875. Portland: Privately Printed and No Date.

Long, Armistead L. “Memoir of General John Bankhead Magruder.” SOUTHERN HISTORICAL SOCIETY PAPERS 19 (1884).

North, Thomas. FIVE YEARS IN TEXAS; OR, WHAT YOU DID NOT HEAR DURING THE WAR FROM JANUARY 1861 TO JANUARY 1866, A NARRATIVE OF HIS TRAVELS, EXPERIENCES, AND OBSERVATIONS IN TEXAS AND MEXICO. Cincinnati: Elm Street Press Co., 1871.

Quarstein, John V. and Moore, J. Michael. YORKTOWN’S CIVIL WAR SIEGE. Charleston, SC: History Press, . 2012.

Rosen, Robert N. THE JEWISH CONFEDERATES. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2000.

Scharf, J. Thomas. HISTORY OF THE CONFEDERATE NAVY. New York: Gramercy Books, 1996.

Settles, Thomas M. JOHN BANKHEAD MAGRUDER: A MILITARY REAPPRAISAL. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State Press: 2009

Silverstone, Paul L. THE CIVIL WAR NAVIES 1855-1883. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2001.

Wallinga, Herman Tommo. THE BOARDING BRIDGE OF THE NORMANS. Groningen, West Germany: J.B. Wolters. 1956

Warner, Ezra J. GENERALS IN GRAY: LIVES OF CONFEDERATE COMMANDERS. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959.

Woodward, C. Vann, ed. MARY CHESNUT’S CIVIL WAR. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981.