This week “in the Land of Submarines” we’re focusing on documenting the Nishimura-style Japanese submarine no. 3746. Previously we talked about its history and our initial assessment of the hull. All this activity is in preparation of moving the sub onto a custom cradle and to a new home.

Since it’s arrival at the Museum in 1946, the sub has been displayed and stored outside. At 35 feet long and 22 tons, keeping it inside wasn’t an option at an institution where space is at a premium. As we prepare the sub for lifting one of our major steps is documenting its condition. After 82 years the hull is still sound, however we’re paying particular attention to the keel.

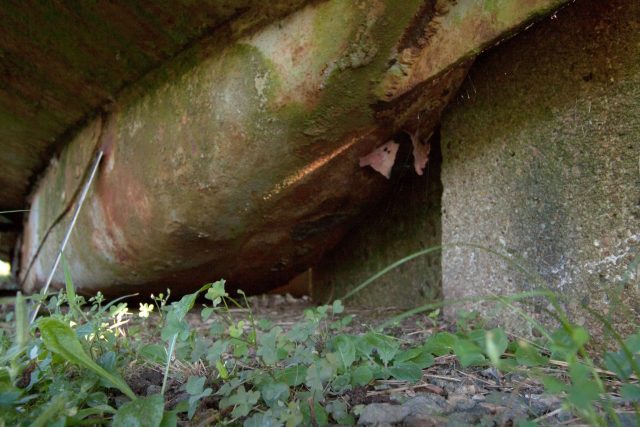

The keel is made of iron plates bolted to the underside of the hull to form a rectangular box. It is reinforced with wooden and iron struts and ballasted with bricks. Often called a “box keel”, it is used for steel hulls where the keel isn’t a structural necessity (acting as the “spine” of the ship), but rather provides balance (keeping things on an “even keel” – literally!). Unfortunately, this design means that the keel is fragile. During the move the keel will be strapped to the hull and supported, but we’re thoroughly documenting it beforehand in case there are any changes.

Condition Reporting: Lesley

As the conservator, it’s my responsibility to write a condition report and take detailed photos. We use these reports to record any damage we see and identify why a problem is occurring. Condition reports are used to write treatment proposals, which outline the actions a conservator plans to take to conserve an object. This report will play an important role when it comes time to work on the sub.

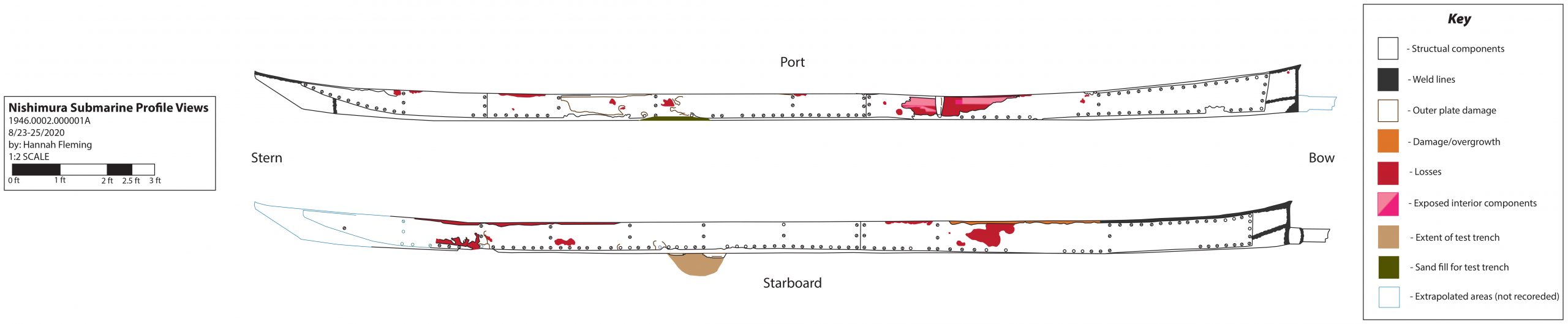

Condition reports are also a time stamp. The report and photos show how the keel looks prior to the move in case it changes during transit. We will do all we can to prevent this, however a test pit dug by our maritime archaeologist, Hannah, confirmed our suspicions that the bottom plates of the keel are thin and fragmented due to prolonged contact with the ground. Partial burial means the iron has interacted with the water, minerals, oxygen, and microbes found in the dirt which cause corrosion. This process is aggravated by any chlorides left in the metal from its life in the ocean. The ends of the keel curve upwards and don’t touch the ground. These areas are well preserved. Our focus during the lift will be on the middle section. Once the sub is in it’s new cradle, the keel will be physically supported with enough air flow to slow corrosion until we can stabilize it.

Archaeological Drawings: Hannah

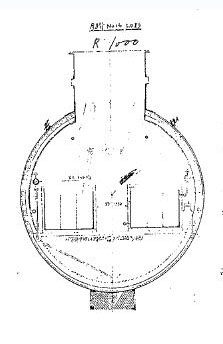

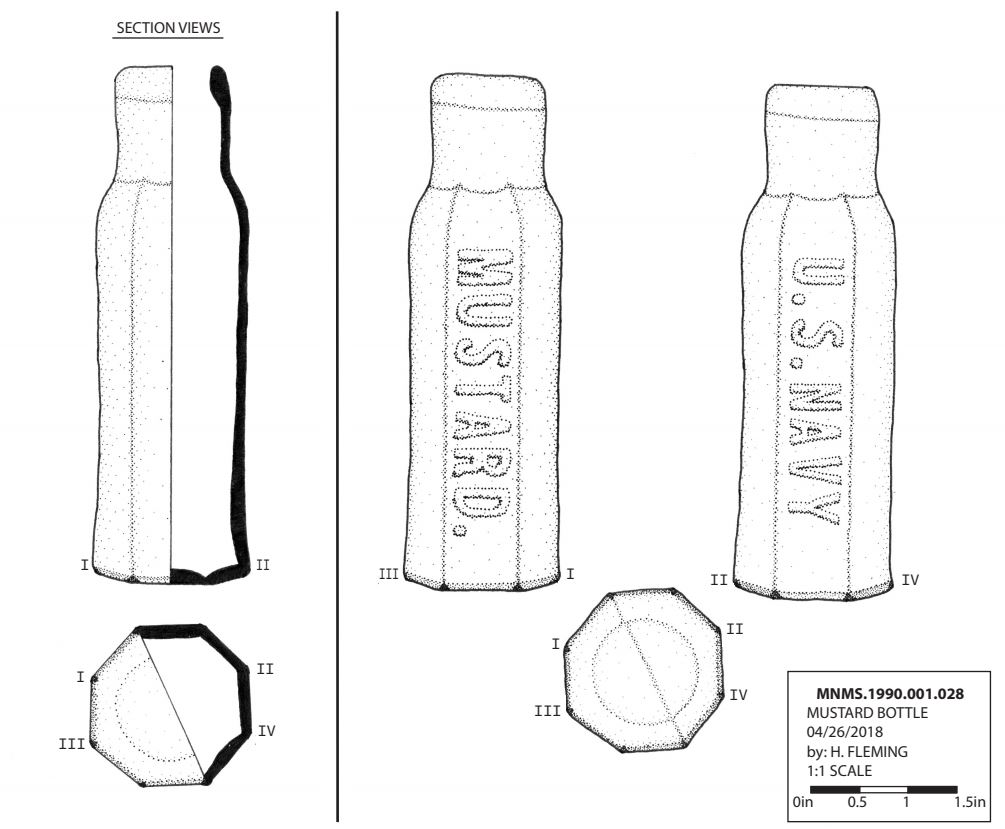

There are several mapping and drawing techniques archaeologists employ to record sites and artifacts. The sub was an interesting challenge in that it is a single artifact (which would normally require a scientific drawing, like shown below), BUT it is a very large artifact, a whole vessel actually, so we questioned whether we needed to make a site plan instead.

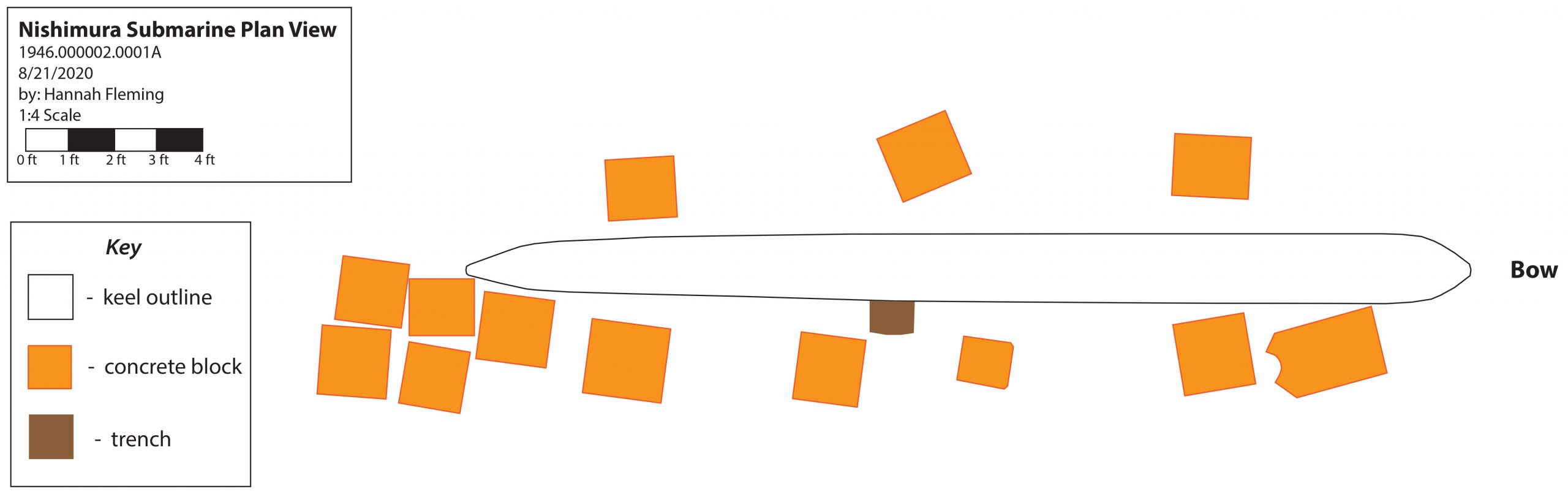

After thinking critically about what we were intending to document, how the drawings would be used, our best and worst case scenarios with the move, and our available time, we decided to do a site map using a baseline, from which we took offset measurements, to record the submarine’s keel only.

This was done in four steps:

- We laid the baseline on the starboard side of the vessel starting with the 0 foot mark somewhere above the bow of the ship, and ran it parallel to the vessel, ending our baseline somewhere behind the ship’s propeller. (Also, to be clear, I know exactly where the line started and ended. We GPS’ed it, but let’s not get bogged down in all the technical data here.) We then took several days to document the port side of the keel in plan and profile views paying particular attention to the areas of degradation and component’s overall shape.

Baseline; made from iron rods, thick twine; a 100-foot flexible tape measure, and zip ties; on the starboard side of the vessel. - We repeated the above step for the port side of the vessel. The port side turned out to be the easier to document because, on this side, there were only three concrete blocks supporting the vessel, while on the starboard side, there were 5 concrete supports and various other concrete slabs laying near the vessel, obscuring our ability to get to the keel. The process took just as long, though, because it rained A LOT while we were trying to finish this side. One day we were outside only 15 minutes before it started to downpour.

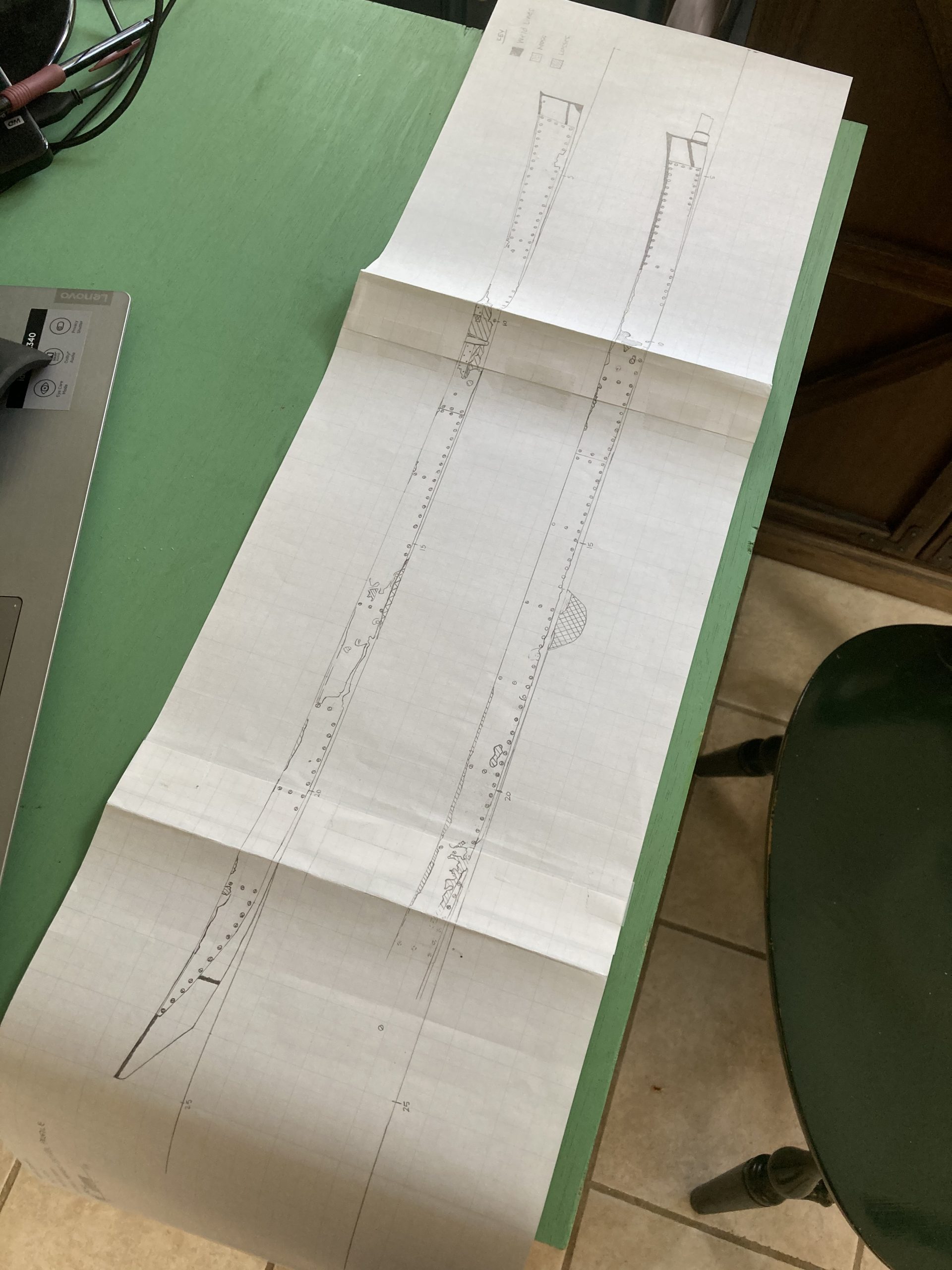

We didn’t make it inside before the downpour. But, not to worry, our notes were still legible! - I was able to take our plan and profile documentation and transfer it into clean, scaled drawings of the keel. I find that this step of data processing is best done right after the data is collected, and before you collect new data the next day. This ensures there is no confusion about where you wrote down what measurement, and what that squiggle was supposed to be (trust me, field notes are not pretty).

The finished, hand drawn profile views. This drawing is longer than my desk! - Finally, after all the data is collected and the scaled drawings have been made, they can be digitized. Digitization makes them pretty, but more importantly, it makes them easy to share. TA DA!

Cool, so what do these drawings tell us? Several things actually, we now have an intimate knowledge of the keel’s construction – down to how far apart each of the screws are – and it’s weakest and strongest points. We better understand where we need to support the keel, and we know exactly what it looks like before the big move. If anything, and I mean anything, weird happens during the move, we know what it looked like before hand so that we can better fix it.

All and all, the more documentation the better. All of these methods serve a particular purpose and capture as specific type of information. Combined they preserve a more complete picture of the sub’s construction and current condition. But there’s one more method we utilize which is so cool, we decided to make it a separate post. So tune in for the next installment: 3D modeling!