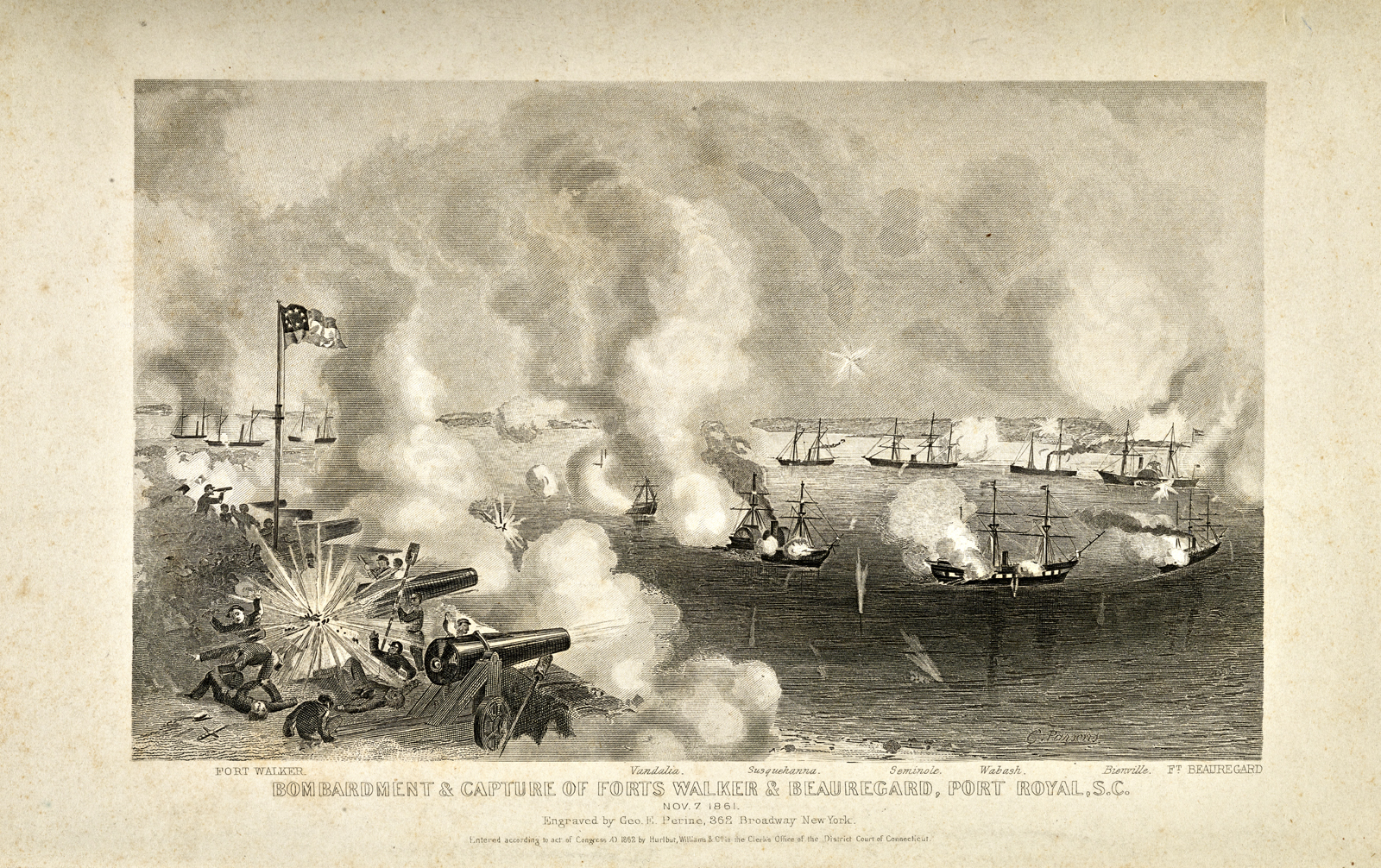

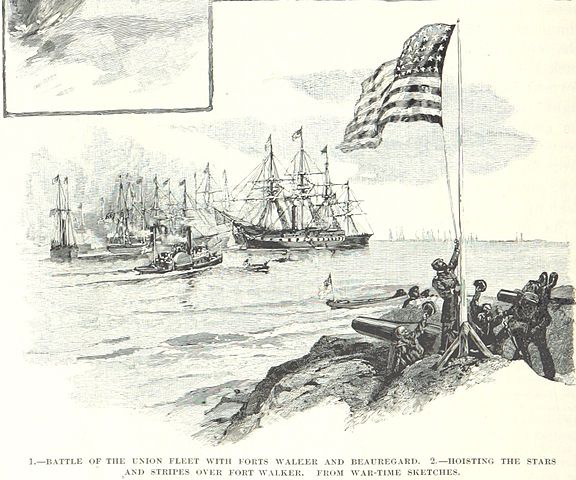

The Civil War’s second major amphibious operation was the capture of Port Royal Sound on November 7, 1861. Flag Officer Samuel Francis Du Pont was the newly minted commander of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. He needed to capture Port Royal Sound, South Carolina, to use as a base for his squadron. Du Pont placed his warships on an elliptical course and forced forts Walker and Beauregard to surrender. The Sound enabled the Federals to maintain a blockade of Charleston and Savannah. The Union’s occupation of South Carolina’s Sea Islands resulted in the Port Royal Experiment. Abolitionists toiled to assist these formerly enslaved people become literate and self-reliant wage earners. Once the Emancipation Proclamation was made law, this coastal region became a recruitment center for African American soldiers.

Blockade Strategy Board

When Fort Sumter fell to the Confederates on April 14, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln declared a blockade of the southern coastline from Virginia to Texas. Winfield Scott, then general in chief of the US Army, suggested the Union’s primary war aim be a blockade of southern ports, including the capture of the Mississippi River. Scott knew that the closure of these ports would end the cotton for cannon trade which was so necessary for the South’s survival. A commission was formed known as the Blockade Strategy Board, also known as the Du Pont Board.

Captain Samuel Francis Du Pont was the commission’s chair. He had served in the US Navy since 1815 and served with distinction on the Pacific coast during the Mexican War as well as being named the commandant of the Philadelphia Navy Yard in 1860.[1.] This board also consisted of Commander Charles Henry Davis, USN; Major John G Barnard, chief engineer of the Department of Washington; and Dr. Alexander Dallas Bache, superintendent of the US Coast Survey Department. All of these men had distinguished prewar careers. Bache (first-in-class 1825) and Barnard (second-in-class 1833) were graduates of West Point.

The Blockade Strategy Board’s duty was to determine how best to cut off access to and from key southern ports. The members made several recommendations noting which ports, like Charleston or Mobile, required a close blocking or capture. Initially, they divided blockade duty into two squadrons: North Atlantic and Gulf Coast squadrons. Almost immediately, Du Pont recognized that just one squadron for each coast would not be as effective due to logistical and administrative requirements. So, each squadron was divided into two, making four squadrons: North Atlantic Blockading Squadron (NABS), South Atlantic Blockading Squadron (SABS), East Gulf Blockading Squadron (EGBS), and West Gulf Blockading Squadron (WGBS).

Key West, Florida, which had remained under Union control, would first serve as the base for the Gulf naval operations. Eventually, it was replaced by Pensacola, Florida, and Ship Island, Mississippi, bases serving each separate squadron. Hampton Roads, Virginia, would serve the NABS. The SABS also needed a station for resupply and repair. The Du Pont Board considered St. Helena Sound, South Carolina, and Fernandina, Florida, as possible bases.

Nevertheless, as chair of the Blockade Strategy Board, Du Pont decided that the new South Atlantic Blockading Squadron would use Port Royal Sound, South Carolina, as its major base and that Du Pont himself would assume command of the Southern squadron. This force was created out of the original Atlantic Blockading Squadron, commanded by Flag Officer Silas Horton Stringham. Stringham resigned so that Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough could assume leadership of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron.[2]

Confederate Preparations

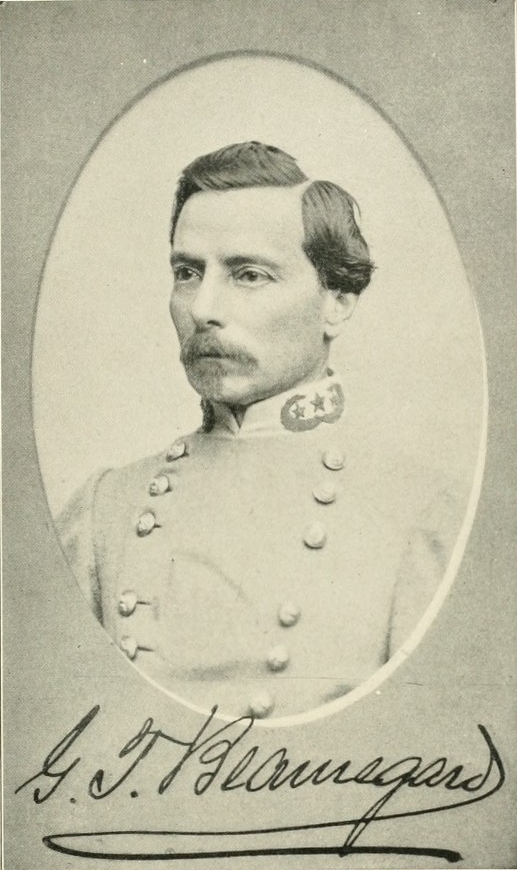

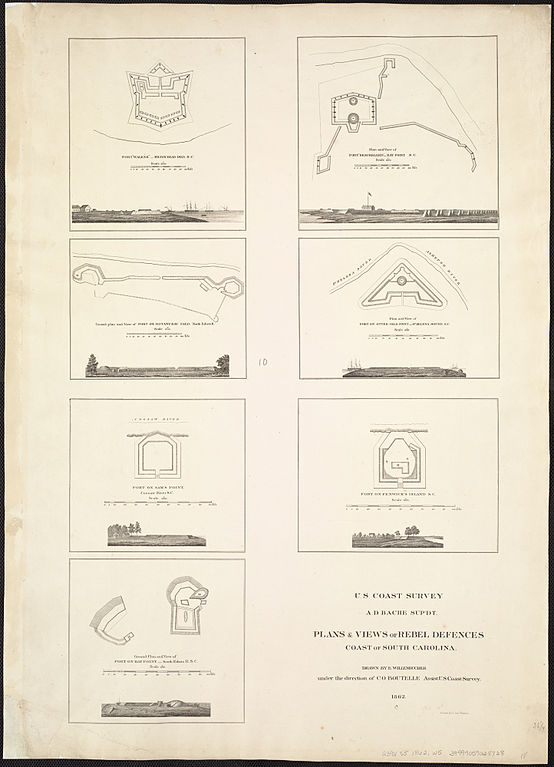

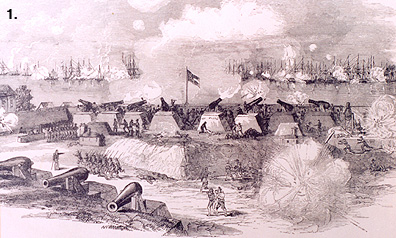

Shortly after the fall of Fort Sumter, the Confederates looked for ways to defend South Carolina’s coastline. General P.G.T. Beauregard thought that Port Royal Sound could not be effectively defended because Phillips Island and Hilton Head Island were too far apart to close the entrance to the sound. However, South Carolina governor Francis Pickens demanded that Beauregard develop plans that would eventually evolve into Fort Beauregard on Phillips Island and Fort Walker on Hilton Head Island. The forts were incomplete by November 1 and neither had adequate armament.

Fort Walker had 21 guns, including one 10-inch Columbiad, and six rifled 32-pounders. Fort Beauregard had 19 guns. The Confederates supported these forts with about 3,000 men.[3]

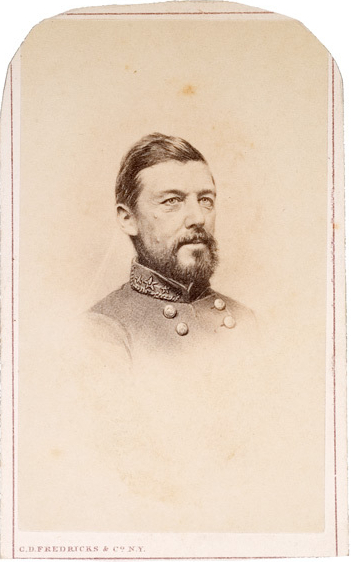

The entire force was commanded by Brigadier General Thomas F. Drayton, an 1828 West Point graduate. A small squadron of four shallow-draft gunboats (CSS Savannah, Resolute, Lady Davis, and Sampson), all mounting two guns apiece, was commanded by War of 1812 and Mexican War hero Flag Officer Josiah Tattnall. [3] These defenses would prove powerless to stop the large Union combined operation headed their way.

Du Pont Plans His Advance

Du Pont organized his fleet of 17 warships in New York and sailed to Hampton Roads, Virginia. There he was to meet up with transports that had been organized at Annapolis, Maryland, to carry Brigadier General Thomas W. Sherman’s (West Point 1836) division to occupy Port Royal Sound and its surrounding communities. Sherman, (no relation to General William T. Sherman) had fought in the 2nd Seminole War and the Mexican War. [4] His 13,000-man command included the brigades of brigadier generals Egbert L. Viele, Isaac I. Stevens, and Horatio G. Wright — all fellow West Pointers. Sherman, with his men on 25 transports, arrived in Hampton Roads on October 22, 1861, to rendezvous with Du Pont’s fleet. The strike force of 77 ships included 20 colliers, six supply vessels, several specialized craft to carry cattle and horses, and 17 warships.

Winfield Scott made it clear to Du Pont and Sherman that the President expected “the most cordial and effective cooperation … and will hold any commander of either branch to a strict responsibility for any failure to procure harmony and secure results proposed.” [5] This was the largest amphibious operation to be launched from Hampton Roads since the beginning of the war.

Heavy Gale Disrupts the Task Force

Bad weather delayed the expedition leaving Hampton Roads. The weather began to clear, showing that the 18-gun sailing sloop of war Valdalia and the 6-gun bark USS Gem of the Sea could escort 20 coal and ammunition ships on October 28, 1861. This task force anchored off the mouth of the Savannah River in an attempt to confuse Confederate leadership. Despite this ploy and Du Pont’s efforts to maintain secrecy by giving his captains sealed orders, the Confederate Secretary of War Judah Benjamin notified General Drayton that “I have just received information that I consider extremely reliable that the enemy’s expedition is intended for Port Royal”[6] The New York Times published an article about the entire expedition naming ships, regiments, and other key information on October 26, 1861[7], which was then printed in the Charleston, SC, newspapers.

The fleet left Hampton Roads on October 29 with 11 warships in a line abreast the transports in three columns in a line ahead with two war vessels guarding the flank and two combat ships holding up the rear. This formation did not last long. On November 1, after the fleet had passed Cape Hatteras, it encountered a hurricane force southeast gale. Du Pont hoisted a signal advising that each vessel should focus on themselves.

Almost immediately several ships became distressed, among them the Governor, which broke its hog braces and lost its smoke stack. The engine blew out a cylinder head. All the men on board bailed and worked the hand pumps. Somehow the Governor stayed afloat during the night. The next morning, the Isaac Smith endeavored to rescue Governor’s crew. Isaac Smith had only survived the evening because it had jettisoned eight of its nine cannons. The gunboat could not help the transport; however, the 44-gun sailing frigate Sabine came upon the scene and was able to save all but seven of the nearly 700 men aboard Governor before it sank.

One transport, Winfield Scott, carrying a Pennsylvania regiment, sprang a major leak and wallowed in the sea with five feet of water in the hull. The ship almost sank; but was towed to safety by the steamer Vanderbilt. The Peerless was also severely damaged by the storm. The 10-gun steam sloop Mohican was able to save 26 crew members before Peerless sank with its entire cargo of horses. The steamers Belvidere, Union, and Osceola, all carrying US Army supplies, vanished during the storm without a trace.[8]

Off Port Royal Sound

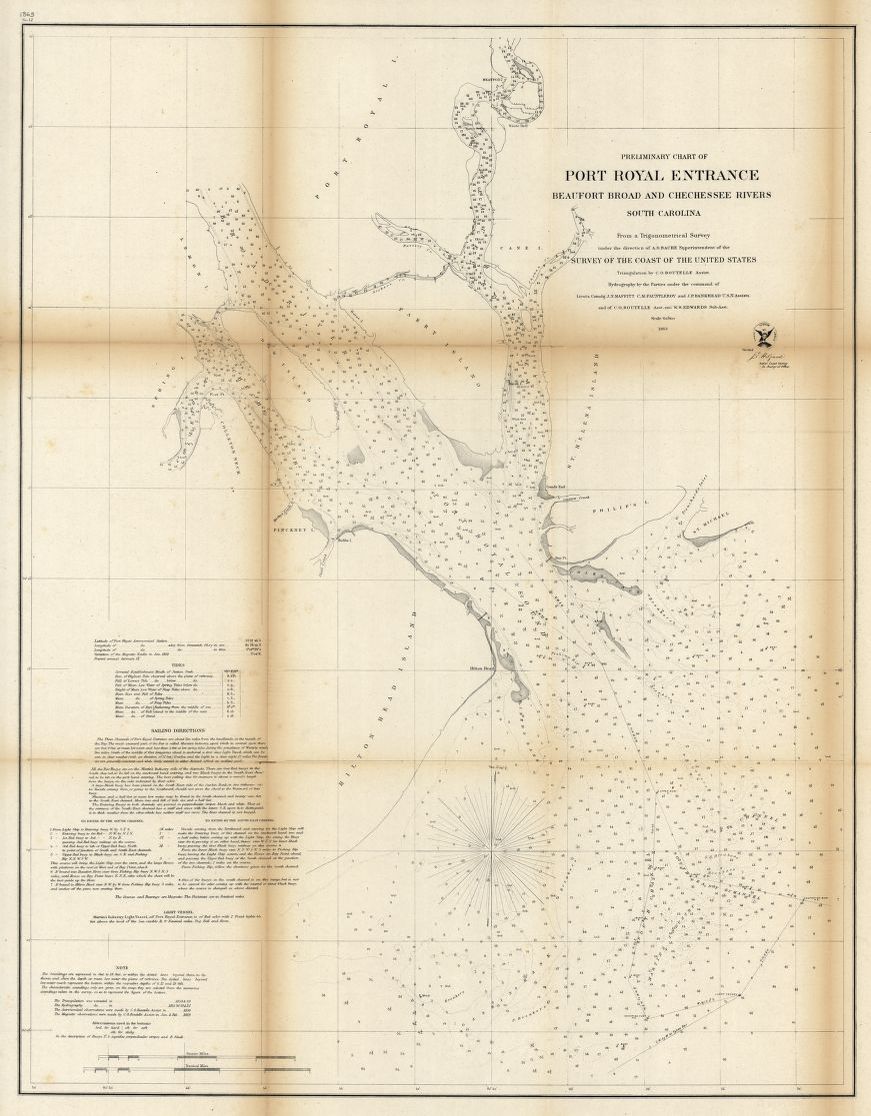

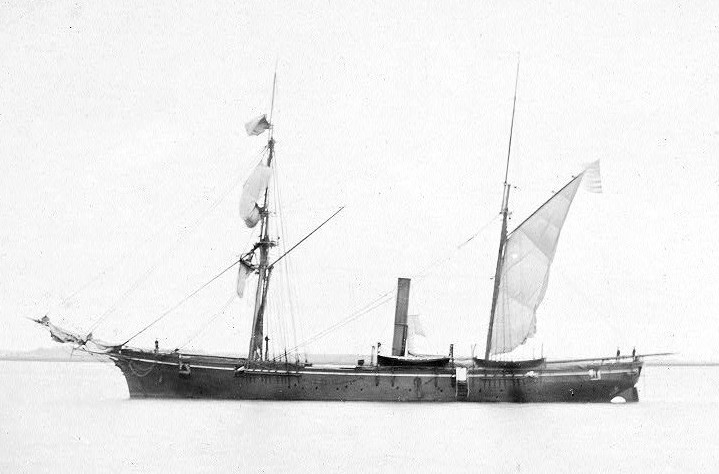

The fleet finally began to come together about 10 miles off the entrance to Port Royal Sound. Du Pont sent the Coast Survey vessel Vixen to mark the channel. It was supported by several gunboats such as Pembina, Seneca, and Ottawa. Tattnall’s gunboats came out to disrupt this operation; yet were quickly chased away. The next day was stormy; nevertheless, these same gunboats, along with Curlew, Isaac Smith, and Pawnee, entered the harbor to test the range of the Confederate cannons. Once again, the Southern gunboats attempted to interrupt the Federal gunboats’ work. Instead, Confederates were once again compelled to retreat.[9]

That same day, Commander Charles Henry Davis, Du Pont’s chief of staff, suggested that the main line of warships be placed on an elliptical course (turn left while in the harbor and repeat) so that the Confederate gunners faced moving targets while the Union ships were able to fire directly into Southern fixed fortifications.[10] Since the entrance to the sound was 2.2 miles wide, beyond the range of Confederate guns, Du Pont knew that his ships should steam into the harbor in mid-channel.

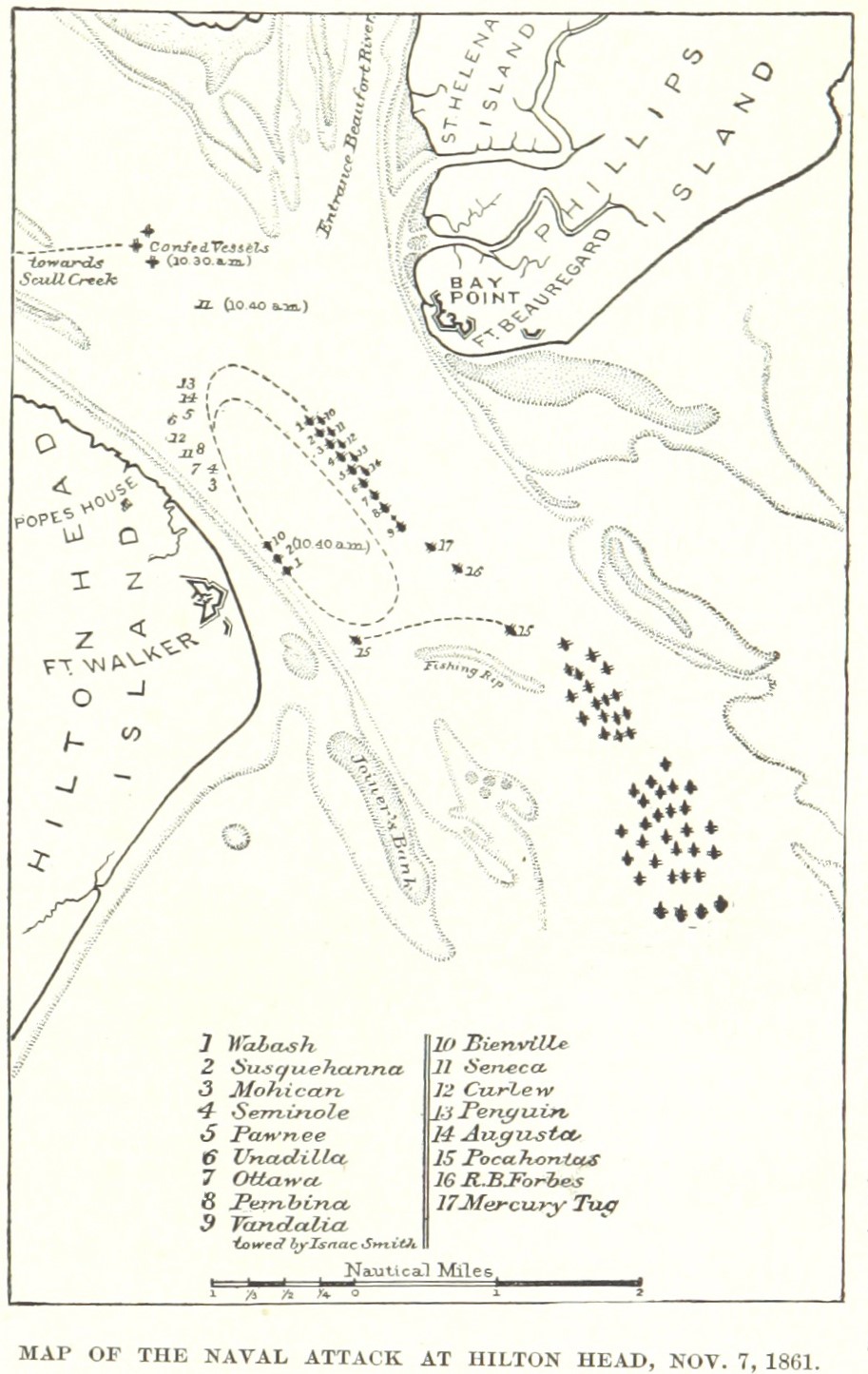

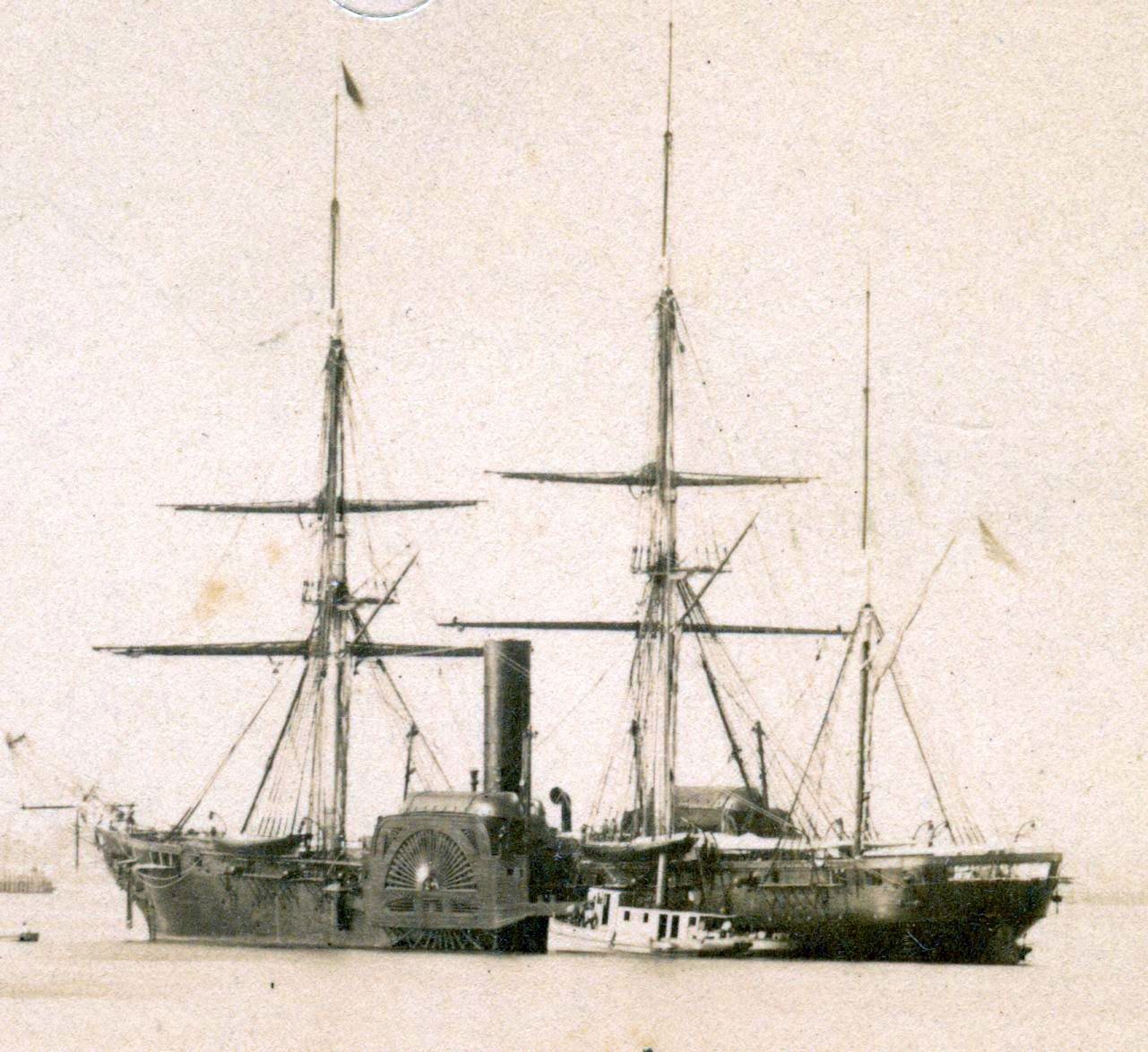

Du Pont planned a line ahead in two columns. The main column featured the 46-gun screw frigate Wabash, 12-gun sidewheeler Susquehanna, 6-gun screw steamer Mohican, 6-gun screw steamer Seminole, 10-gun steam sloop Pawnee, 4-gun screw gunboat Unadilla, 4-gun screw gunboat Ottawa, 4-gun screw gunboat Pembina, and the 4-gun sailing sloop Vandilla. Isaac Smith towed Vandilla into action. Starboard of the main column was a flanking squadron, including Bienville, Seneca, Curlew, Penguin, and Augusta. [11]

Flag Officer Du Pont had been advised before that Gen. Sherman’s brigades would not participate in the attack. Sherman noted that many of his units had thrown their muskets overboard to stay afloat during the storm. The gale also took away all of his boats needed to land his troops to support the Union attack upon the Confederate forts. Sherman ended his statement that he could only support the navy once the transport Ocean Express, containing arms and ammunition, arrived.[12]

Attack

At about 9 a.m. on November 7, Du Pont ordered his men to “Prepare for Action.”[13] Fort Walker fired the day’s first shot toward the oncoming fleet at 9:26 a.m. Both the Confederates and Federals aimed high; nevertheless, the ships and forts were struck by shot and shell. When the fleet took its first turn, several vessels such as Mohican, dropped off of the column. The gunboat’s commander, Sylvanus Gordon, discovered that his ship could enfilade Fort Walker without being exposed to return fire from the fort’s water battery. Several other ships joined Mohican, such as the gunboats Seneca and Augusta, causing great havoc within the earthwork.[14]

Du Pont continued on his course and was able to make three circuits with Wabash, Susquehanna, and Bienville. Eventually, the 1-gun sloop Pocahontas, delayed by the storm, arrived and joined Du Pont’s column. Pocahontas was commanded by Percival Drayton, brother of the Confederate commander Thomas Drayton. [15]

By about 1 p.m., Fort Walker, with only three cannons still mounted, was abandoned in such haste that the Southerners left behind their personal belongings and failed to spike the remaining guns. Commander John Rodgers, seeing that the fort was unoccupied, was rowed ashore to raise the United States flag over Fort Walker. Upon seeing the enemy’s flag flying over their companion fort, Fort Beauregard surrendered.[16]

Aftermath

The battle featured fierce bombardments which had little effect. The Confederates suffered 11 killed, 47 wounded, and four missing. In turn, the Northern fleet incurred casualties of eight killed and 23 wounded.[17] Once Port Royal Sound was under Northern control, the Federals occupied Beaufort and St. Helena Sound. Port Royal was then transformed, shortly thereafter, as a huge supply and repair base, supporting the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron until the war’s conclusion.

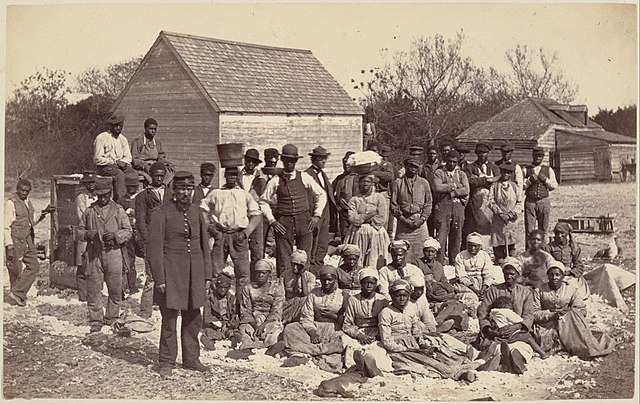

Port Royal Experiment

Once the Union forces controlled Port Royal Sound and the Sea Islands along coasts of South Carolina and Georgia, a new issue arose as to what to do with the former enslaved population. Union Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase immediately sought to gather all the cotton that had been harvested and sell it to northern mills to generate more money for the war effort. Colonel William H. Reynolds was sent to Beaufort, SC, to commandeer all of the cotton. The next question was how to motivate the spontaneously freed people of African descent to continue to produce cotton.

Chase was a leading abolitionist. He had taken note of Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler’s “Contraband of War Decision,” declaring that enslaved persons reaching Union lines would be considered as contrabands. They were held in a state between freedom and enslavement. These contrabands considered themselves free. The Confiscation Act of August 1861, passed by Congress, codified these actions. On the Virginia Peninsula, protected by Fort Monroe, contrabands were taught how to read and write by the American Missionary Association. Many contrabands were employed supporting US Army activities. They also could join the US Navy in an effort to help free their brethren.

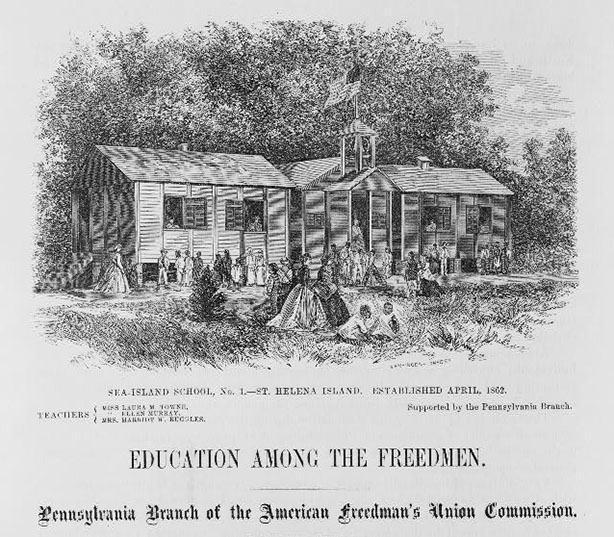

When the Federals captured Port Royal Sound, all of the area’s formerly enslaved people considered themselves free. Accordingly, Chase then instructed a member of the American Missionary Association, Reverend Edward Lillie Pierce, to go to Port Royal to ascertain the Freedmen’s needs as well as their willingness to continue cotton production. Just as in Hampton, Pierce recognized the need for work supervision and improved living conditions as well as the need for schools. These Freedmen would be paid for their work and eventually, the African-American citizens of the Sea Islands would become landowners and begin their new lives as equal citizens.[18].

Recruitment

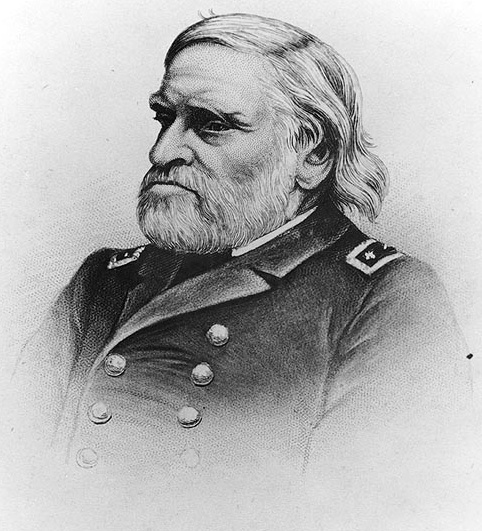

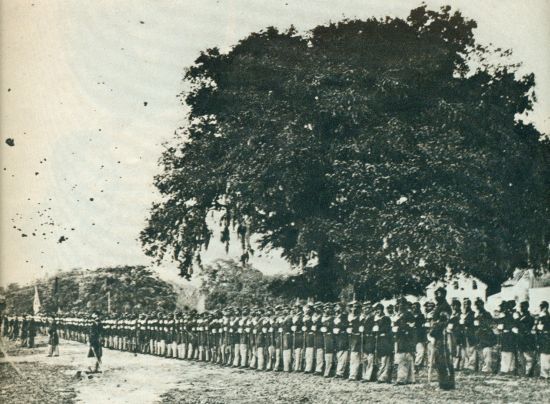

Major General David Hunter, also known as “Black Dave,” for his coal-black hair, graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1822. He fought in the Second Seminole War and the Mexican War. By 1860, he was stationed at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and while there became an ardent abolitionist. He fought at the Battle of First Manassas and was severely wounded.

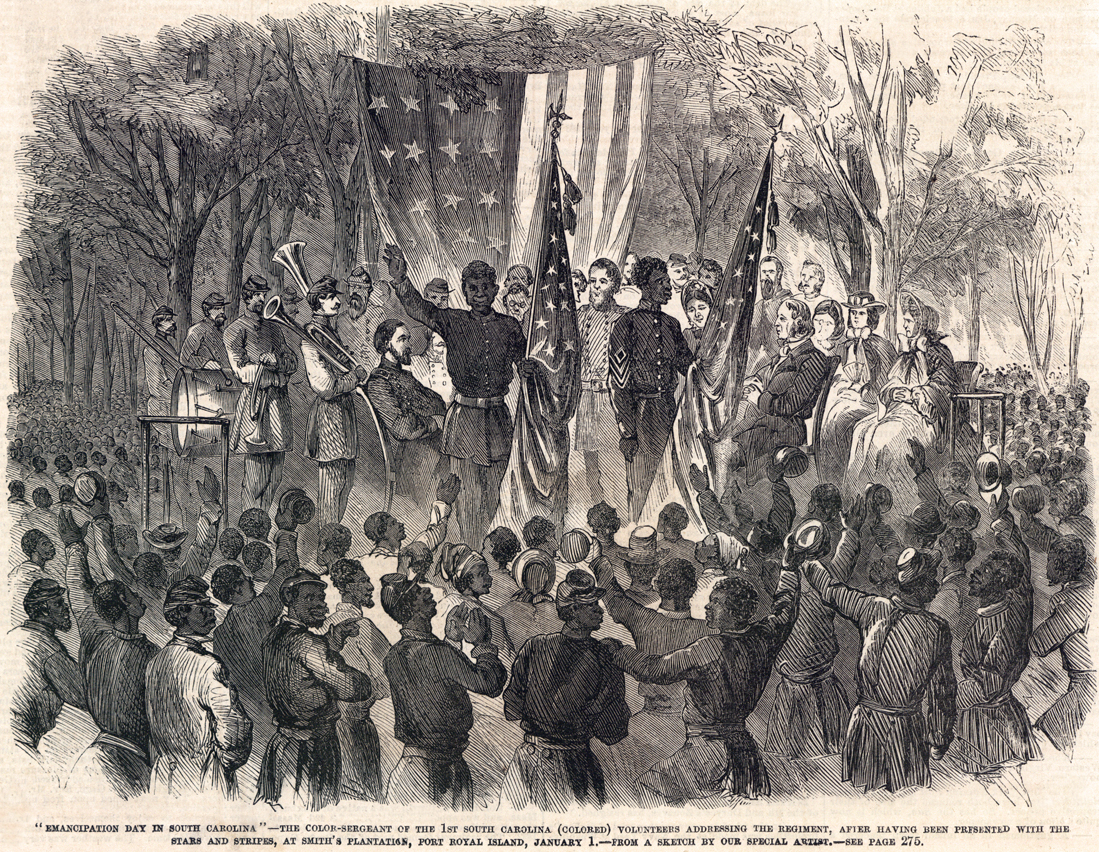

Hunter was later transferred as commander of the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida in 1862. He took this opportunity to order the emancipation of enslaved people within his Department. President Abraham Lincoln quickly rescinded this order. Then General Hunter issued his general order number 7 which was to begin efforts to establish the 1st South Carolina (African descent) Regiment. The order to abandon this recruitment effort was ignored by Hunter. Eventually, the unit would be mustered into US service in 1863.[19]

The capture of Port Royal Sound had tremendous influence on the Union war effort as well as serving as the transformation of formerly enslaved persons into Freedmen, revitalizing them as citizens of the United States.

Notes

1 Mark M. Boatner III, The Civil War Dictionary, New York: Vintage Books, 1988, p.352.

2 Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies During the War of the Rebellion, (Hereinafter referred to as ORN), ser. 1, vol. 12, pp. 195-206.

3 ORN, ser. I, vol.12, p.208.

4 Boatner, p.750.

5 J. Thomas Scharf, History of the Confederate Navy From Its Organization to the Surrender of Its Last Vessel, New York: Gramercy Books,1996, p.38.

6 Richard S. West Jr., Mr. Lincoln’s Navy, New York: Longmans, Green and Company, 1957. pp. 82-83.

7 New York Times, October 26, 1861.

8 Howard P. Nash Jr., A Naval History of the Civil War, London: Thomas Yoseloff, LTD, 1972, pp.58-60.

9 Ibid, p. 61.

10 ORN,1,v12, 262-266.

11 West, pp. 85-86.

12 Robert M. Browning Jr., Success Is All That Was Expected: The South Atlantic Blockading Squadron During the Civil War, Dulles, Virginia: Brassey’s Inc., 2002, p. 32.

13 Nash, p. 61.

14 Browning, pp. 35-38.

15 Nash, p. 62.

16 ORN,1, vol. 12, pp. 262-266.

17 Ibid, p. 306.

18 “Essential Civil War Curriculum,” Virginia Center for Civil War Studies, Virginia Tech University online. Accessed October 31, 2020. ttps://www.essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com/terms.html

19 Ezra J. Warner, Generals in Blue: Lives of Union Commanders, Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, 1964, p. 243.

Bibliography

Browning, Robert M., Jr. Success Is All That Was Expected: The South Atlantic Blockading Squadron During the Civil War. Dulles, Virginia: Brassey’s Inc., 2002.

Boatner, Mark M., III. The Civil War Dictionary. New York: Vintage Books, 1988.

“Essential Civil War Curriculum,” Virginia Center for Civil War Studies, Virginia Tech University online. Accessed October 31, 2020. https://www.essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com/terms.html

Official Record of the Union and Confederate Navies During the War of the Rebellion. Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office, 1901.

Nash, Howard P., Jr. A Naval History of the Civil War. London: Thomas Yoseloff, LTD, 1972.

New York Times, October 26, 1861.

Scharf, J. Thomas. History of the Confederate Navy From Its Organization to the Surrender of Its Last Vessel. New York: Gramercy Books, 1996.

Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of Union Commanders. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. 1964.

West, Richard S., Jr. Mr. Lincoln’s Navy. New York: Longmans Green and Company. 1957.