At the onset of the Civil War, General Winfield Scott noted that a Union victory could be achieved by controlling the Mississippi River. Scott believed the entire Mississippi Valley could be controlled using only 12 to 20 gunboats and 60,000 soldiers. More resources would eventually be needed; however, the Federals ultimately enabled, as President Abraham Lincoln said, the ‘Father of All Rivers to flow unvexed to the sea.’

Because the Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles was preoccupied with establishing a blockade of the Confederate coastline, he placed control of the Western Gunboat Flotilla to the War Department. This action would give a strong unity of command as the Union army and naval forces endeavored to wrestle the river from the Confederacy. Commander John Rodgers was initially placed in command of the flotilla; however, he was soon replaced by Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote.

Before Foote arrived, Rodgers had purchased three wooden steamers: Lexington, Conestoga, and Tyler; nevertheless, thanks to James Eads, the Union began constructing ironclads designed by naval architect Samuel M. Pook. These seven ironclads were called ‘Pook’s Turtles’ and eventually gave the Union control of the upper Mississippi Valley from Columbus, Kentucky, to Vicksburg, Mississippi.

Despite the Western Gunport Flotilla’s success at engagements such as Island No. 10, Memphis, and Fort Henry, the City-class gunboat and other similar casemated Union ironclads had numerous flaws. They were not shot-proof, having only 2.5 inches of iron protecting the casemate, and no stern armor was added to cover the rear paddle wheel.

The decks were not plated, making the ships vulnerable to plunging shot. City-class ironclads had no hull protection and, if holed, the lack of watertight compartments would result in the rapid sinking of the ironclad. Despite all these weaknesses, the City-class ironclads, timberclads, and tinclads served the Union well. They enabled the capture of western and central Tennessee, northern Alabama, and much of the Mississippi Valley.

Monitor Fever

The March 9, 1862 Battle of Hampton Roads created excitement throughout the North as the nation clamored for more turreted ironclads. This fever spread westward, and turreted gunboats had to be added to the Union Mississippi Squadron to ensure victory. Four different river monitor classes were developed; however, only seven of nine river ironclads laid down participated in active operations.

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nhhc-series/nh-series/NH-49000/NH-49790.html.

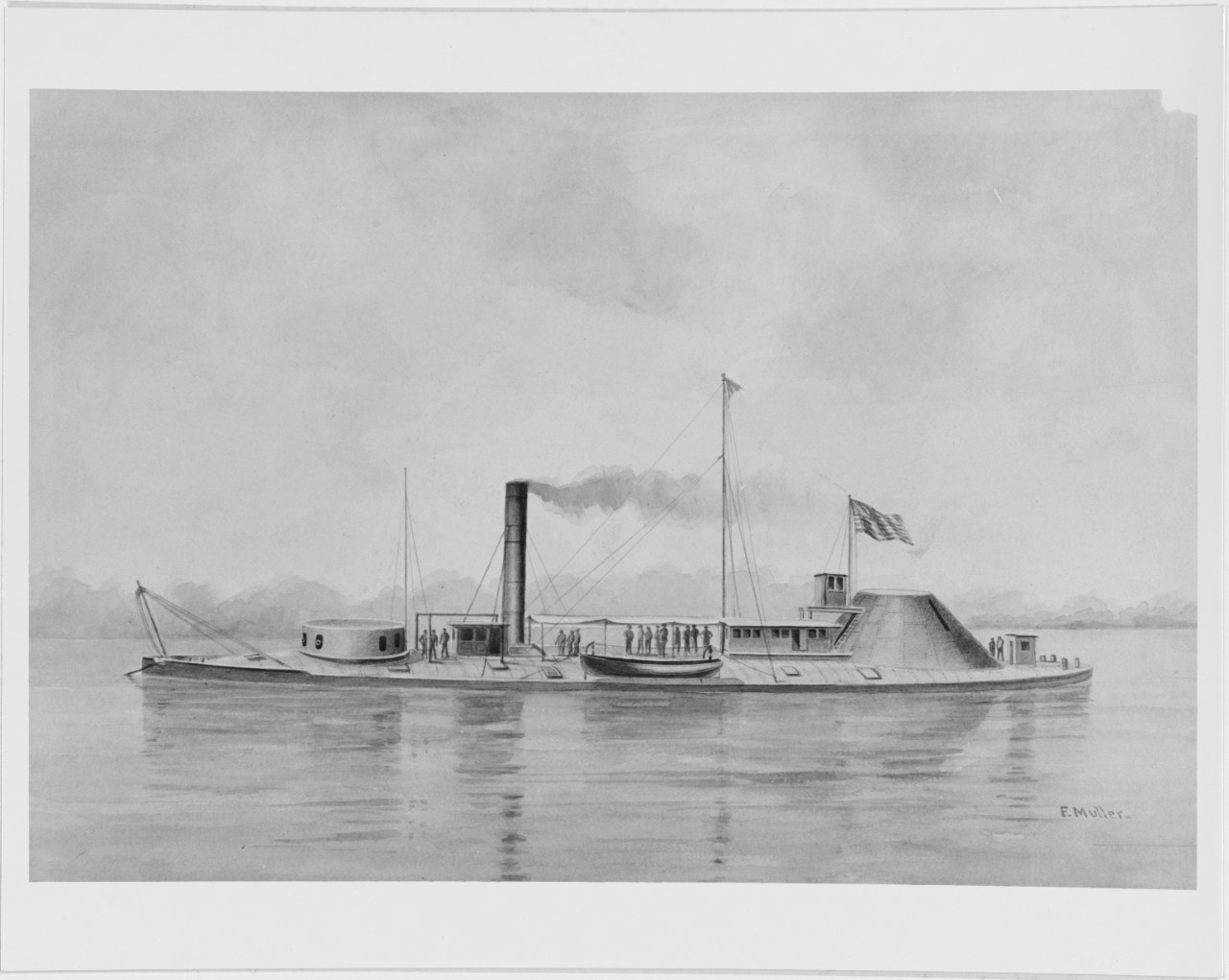

The first class of river monitors was the Neosho-class. This two-vessel design consisted of USS Neosho and USS Osage and were the only ironclad monitors using sternwheels. Designed by James Eads and constructed at Union Ironworks, Carondelet, Missouri, these ironclads were launched in early 1863.

Characteristics:

Tonnage: 523

Length: 180 ft.

Beam: 45 ft.

Draft: 4 ft. 6 inches

Speed: 10.6 knots

Machinery: one horizontal steam engine, sternwheel with four boilers

Armament: two XI-inch Dahlgren shell guns

Armor: 6 inches turret (Ericsson design), 2.5-inch sides, 1.25-inch deck, 2.5 inches hull

The turret was located at the bow of each vessel and a deckhouse was between the funnel and the stern wheel. The pilothouse sat atop the rear deckhouse, and another deckhouse was placed between the steam-powered turret and funnel.[1]

A Failed Design

USS Ozark was yet another individual class of river monitor. The warship was built to Navy Department design by Hambleton, Collier & Company of Peoria. Underpowered and unwieldy, this monitor could be described as an experimental warship. It proved to be a failure as it had several structural flaws. The two twin-cylinder steam engines powered four-bladed propellers. The hull was subdivided by three transverse and three longitudinal watertight bulkheads. The monitor was fitted with three rudders. The Ozark had an Ericsson-designed turret with an armored pilothouse on top. The officer’s quarters were in a pine deckhouse. A hurricane deck was later installed between Ozark‘s two funnels. Yet another improvement was made to the monitor’s armament after the Red River Campaign, which added four Dahlgren shell guns on pivot mount on the deck. These guns were eventually placed within a wooden casemate.

The monitor Ozark was selected to use an experimental ‘underwater battery’ which consisted of a IX-inch Dahlgren firing through a pipe in the side of the hull beneath the waterline. This concept proved to be a failure. [2]

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command. https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/OnlineLibrary/photos/sh-usn/usnsh-o/ozark.htm.

Characteristics:

Tonnage: 578

Length: 180 ft.

Beam: 50 ft.

Draft: 5 ft.

Machinery: two 2-cylinder engines with four screws and six boilers

Speed: 7.9 knots

Armor: 6 inches turret, 2.5 inches sides, 1.25 inches deck

Armament: two XI-inch Dahlgrens, one X-inch Dahlgren, three IX-inch Dahlgrens

Compliment: 120. [3]

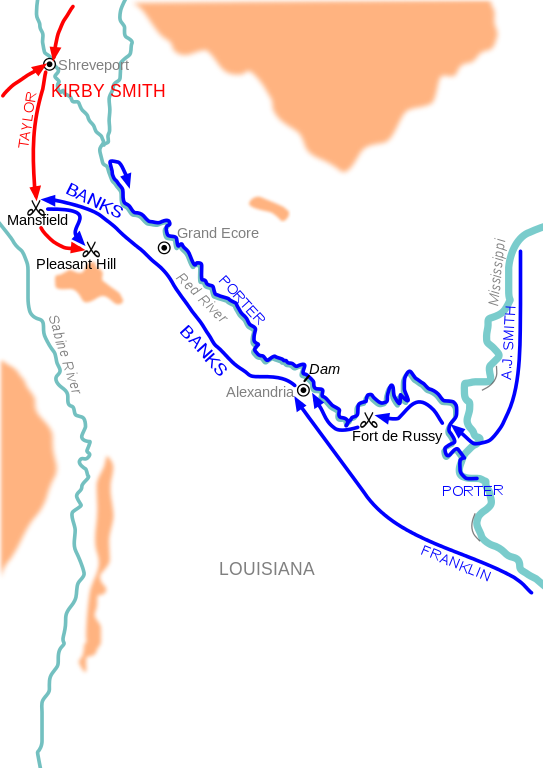

These first three monitors were used during Major General Nathaniel P. Banks’s Red River Campaign. The campaign depended on the cooperation of Rear Admiral David D. Porter’s Mississippi Squadron; Major General Nathaniel Banks and his 20,000-man army, part of M.G. W.T. Sherman’s Army; 15,000 men commanded by Brigadier General Andrew J. Smith, joined Bank’s army; and another 7,000 soldiers from the Department of Arkansas, led by Major General Frederick Steele, supported Banks’s campaign. Their destination was Shreveport, Louisiana. [4]

Purpose of Campaign

President Abraham Lincoln had authorized Banks to capture the Confederate supply depot at Shreveport and then the Confederate capital of Louisiana. His goal: prevent a Confederate alliance with French-supported Imperial Mexico, secure vast amounts of Louisiana and Texas cotton for Northern mills, and organize Louisiana’s Union government. Using the Union gunboats in the Red River, Banks believed he could secure Shreveport, establishing it as a base to conquer Texas. [5]

Porter’s Mississippi Squadron

David Porter’s gunboats guarded Union transports and provided artillery support as Banks’s army moved upriver. Admiral Porter’s command consisted of the ironclads Essex, Benton, Choctaw, Chillicothe, Ozark, Louisville, Carondelet, Eastport, Pittsburg, Mound City, Osage, and Neosho, as well as the wooden steamers Lafayette, Ouachita, Lexington, Fort Hindman, Cricket, and Gazelle. [6]

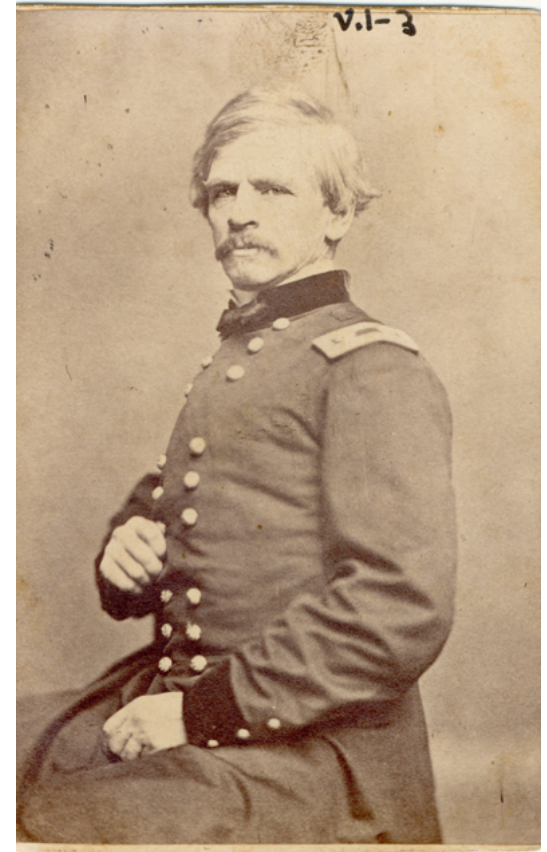

Forward and Retreat

Confederate troops under the command of Lt. General Richard Taylor endeavored to block the Federal advance. Porter was able to get his ships past the falls at Alexandria with the loss of a hospital ship. On April 8, 1864, Banks was defeated by Taylor at the battle of Mansfield, even though Banks secured a victory at Pleasant Hill on April 9, 1864. It was a tactical Union victory; however, Banks retreated. General Smith’s command was returned to Sherman’s Army. Skirmishes occurred between Confederate infantry, cavalry, and artillery almost daily versus Union troops and gunboats. [7]

Battle of Blair’s Landing

On April 12, 1864, the Confederates discovered that several Union transports and gunboats were grounded near Blair’s Landing. USS Osage, captained by Lieutenant Commander Thomas O. Selfridge, ran aground. Selfridge had to defend his monitor in an unusual fight. [8] Brigadier General Thomas Green, a hero of the Texas War of Independence and the Mexican War, decided to attack Osage. Green “was a man, who, when out of whiskey, was a mild-mannered gentleman, but when in supply of old bursthead was a fighter.” At Blair’s Landing, “well-fortified with Louisiana Rum,” Green, with a yell, told his men, “he was going to show them how to fight.” The charge was made on horseback. Green was killed early in the action, a “cannonball taking out the top of his head.” [9]

Damage and Loss

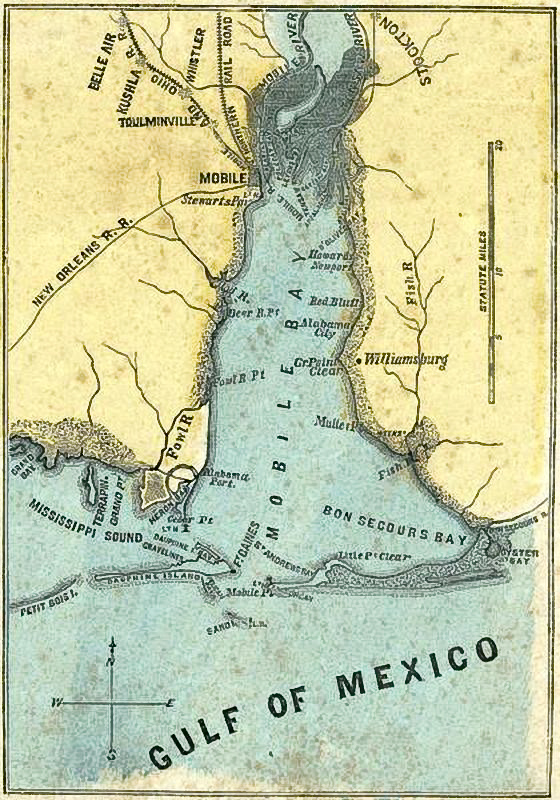

After escaping the Red River, Osage grounded in May 1864 near Helena, Arkansas, and could not be refloated until November. This caused the monitor to hog, damaging the structural integrity of its hull. Temporary repairs enabled Osage to go to Mound City for an overhaul. Then the ironclad was transferred to the West Gulf Blockading Squadron in Mobile Bay, Alabama, on February 1, 1865. The Osage participated in the bombardment of Spanish Fort on March 27, 1865, and was sunk by a torpedo in the Blakeley River, with the loss of two lives, on March 29, 1865. The Osage was later refloated and sold on November 22, 1867. [10]

Showing the Principal Strategic Places of Interest, 1861. Public domain.

Bailey’s Dam

USS Ozark was one of the several ironclads in Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter’s Mississippi Squadron trapped by falling waters above Alexandria, Louisiana. The water over the falls had dropped to 3 feet, 4 inches, and Porter’s ships required at least seven feet of water to pass through the rapids. Lt. Colonel Joseph Bailey, Chief Engineer of the 19th Corps, suggested building wing dams to raise the water level. The 758-foot-wide Red River dams were begun on April 28; however, two barges broke on May 9. Although four ships, including USS Lexington, were able to pass through the original dam, new wing dams were built farther up the river to lessen pressure on the main dam. The dams were built by the 29th Maine, 97th USCT, and 99th USCT regiments. On May 13, USS Mound City was the first to pass through the dam, followed by most of the Squadron. [11]

After the war, Ozark was sold to an undisclosed buyer. Louisiana Governor William Pitt Kellogg used the ironclad to transport soldiers and police from New Orleans to apprehend the perpetrators of the Colfax Massacre. There is no further record of this vessel’s existence.[12]

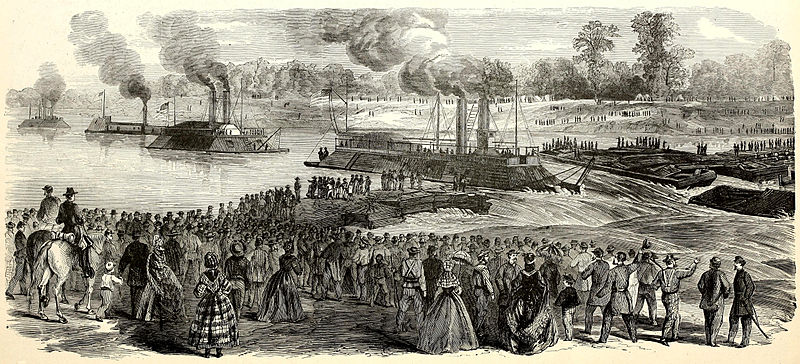

Frank Leslie’s Scenes and Portraits of the Civil War, 1894. Public domain.

On to Nashville

USS Neosho survived the Red River Campaign. During the Franklin-Nashville Campaign, Neosho and the casemate ironclad Carondelet bombarded Confederate batteries on the Cumberland River near Bell’s Mills, Tennessee, on December 6, 1864. Hit more than 100 times during the action, Neosho was not seriously damaged, and it bombarded the Confederate right wing during the Battle of Nashville, December 15-16, 1864. The monitor was sold on August 17, 1867.[13]

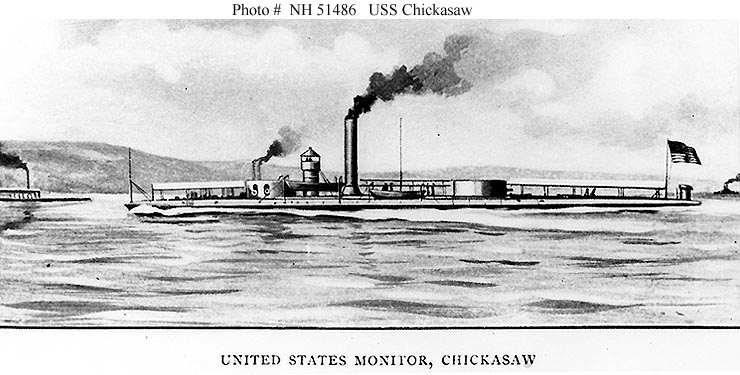

Milwaukee-Class Monitors

The double-turreted monitor Milwaukee-class consisted of four ironclads: Chickasaw, Kickapoo, Milwaukee, and Winnebago. James Eads received the contract to build these monitors; however, he only constructed Milwaukee and Winnebago at his Union Iron Works in Carondelet, Missouri. Eads, who received support for obtaining this contract from Congressman Frank P. Blair Jr., the owner of Union Iron Works, subcontracted Chickasaw‘s construction to Thomas G. Gaylord and Kickapoo to G. B. Allen. Both shipyards were alike, except USS Chickasaw had two Ericsson-designed turrets; whereas, the others had an Eads-design turret forward and an Ericsson-turret aft. Otherwise, the monitors were alike.

Ericsson turrets had their entire weight on a central spindle that had to be elevated for the turret to rotate. Eads’s turrets rested on several ball bearings underneath the other edge of the turret. The guns were mounted on a steam-powered platform that moved up and down to reload the guns below deck, safe from enemy fire. A steam engine was used to rotate the turret and all other functions within the turret, including running out the guns. Eads’s turrets only required six men to operate. [14]

Characteristics:

Displacement: 1,300 tons

Length: 229 ft.

Beam: 56 ft.

Draft: 6 ft.

Machinery: two 2-cylinder horizontal non-condensing steam engines driving to propellers

Speed: 9 knots

Compliment: 138-men

Armament: two XI-inch Dahlgren shellguns in each turret.

Armor: turrets – 8 inches; sides – 3 inches; deck – .75 – 1.5 inches; pilothouse – 3 inches

[15]

Into Action

The first two monitors placed into service, Chickasaw and Winnebago, were eventually detailed to the West Gulf Blocking Squadron. On August 5, 1864, these twin turreted monitors were third and fourth in line behind the heavily armed Canonicus-class monitors Manhattan and Tecumseh. When Tecumseh was sunk by a torpedo, the river monitors held their position in front of Fort Morgan. Both monitors were damaged. The Winnebago had its aft turret jammed, and Chickasaw had its funnel riddled with holes. [16]

The Fight with CSS Tennessee

When CSS Tennessee attacked the entire Union fleet after it had passed Forts Morgan and Gaines at about 9:00 a.m., the Confederate ironclad was rammed several times. USS Chickasaw found a position off Tennessee’s stern and repeatedly fired with XI-inch shot from a range of 10 to 50 feet. The 136-pound shot failed to penetrate Tennessee’s armor; nevertheless, the shells jammed the stern gunport shutter and cut the exposed steering chains, leaving the ironclad unable to steer. The next shot hit the port sill while under repair, killing the machinist and wounding Rear Admiral Franklin Buchanan. The ironclad soon lowered its flag. Both monitors participated in the bombardment of Forts Morgan and Gaines until they surrendered.[17]

J.O. Davidson, artist. Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command. https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/OnlineLibrary/photos/sh-usn/usnsh-c/chika-k.htm.

By March 1865, Chickasaw and Winnebago were joined by their sister ships, Kickapoo and Milwaukee. On March 28, Milwaukee sank after striking a torpedo in the Blakeley River, east of Mobile, Alabama. The surviving ships were decommissioned and sold on September 12, 1874. The Chickasaw was converted into a sidewheeler and served as a coal and railroad ferry until scuttled in 1944. [18]

The Last River Monitors

The last class of river monitors was the Marietta-class. These two light draft, single turret, flat bottomed monitors had iron hulls and two funnels abreast. The Marietta and Sandusky were built by Tomkinson, Hartapee & Co., of Pittsburg, Pennsylvania.

Characteristics:

Tonnage: 479 tons

Length: 173.11 ft.

Beam: 52 ft.

Draft: 5 ft.

Machinery: 4 screws, 2-cylinder engines with 6 boilers

Compliment: 100

Armament: two XI-inch Dahlgrens

Armor: 6 inches turret; 1.25 inches sides

Both ironclads were completed in December 1865 but were never commissioned. These two ironclads were laid up at Mound City, Illinois. Marietta was renamed Circe on June 15, 1869, then renamed Marietta on August 10, 1869. Likewise, on June 15, 1869, Sandusky was renamed Minerva and returned to its original name on August 10, 1869. Both Marietta-class ironclads were sold on April 12, 1873. [19]

Miniature model. Joseph F. Schmitt Sr., model maker.

The Mariners’ Museum 1995.0034.000099.

Conclusion

River monitors were an improvement over City-class and other types of casemate ironclads. The Milwaukee-class was probably the best design. With two turrets and four XI-inch Dahlgrens each, they featured good firepower. Furthermore, the Eads-turret design proved superior to the Ericsson-type turret. Their six-foot draft made these ironclads perfect for operations in Mobile Bay, Alabama, near the end of the war.

Endnotes

- Paul H. Silverstone, Civil War Navies 1855-1883, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2001, pp. 111-112.

- Donald L. Canny, The Old Steam Navy: The Ironclads, 1842-1885, Annapolis, Maryland: US Naval Institute. 1993, pp. 110-112.

- Silverstone, p. 112.

- Patricia L. Faust, Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia Of The Civil War, New York: Harper Perennial, pp. 620-621.

- IBID, pp. 619-620.

- Naval History Division Navy Department, Civil War Naval Chronology 1861-1865, Washington: US Government Printing Office, 1971, Vol. IV, p. 30.

- Faust, pp. 621-622.

- John V. Quarstein, The Monitor Boys, Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2007, p. 288.

- John D. Winters, The Civil War In Louisiana, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963, p. 239.

- Silverstone, pp. 111-112.

- Faust, p. 33.

- Lee Anna Keith, The Colfax Massacre: The Untold Story Of Black Power, White Terror And The Death Of Reconstruction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 122-137.

- Civil War Naval Chronology, Vol. IV, p. 146.

- Canney, pp. 114-116.

- Silverstone, pp. 112-113.

- Canney, pp. 117-118.

- John V. Quarstein, A History Of Ironclads: The Power Of Iron Over Wood, Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2006, p.201.

- Silverstone, pp. 113-114.

- IBID, p. 114.