One of the biggest challenges museum curators and collectors regularly encounter is the loss of historical information, known as dissociation, of the objects in their collections. Unless someone takes the time to physically write down an object’s history and makes sure that information cannot be lost, then an artifact’s full history can never be known. When an object suffers from dissociation it is the role of curators, historians, or collectors, to try and rebuild some of its history using whatever information the artifact can provide. While preparing for an upcoming gallery installation, I began researching a beautiful octant in the Peter Ifland Collection1 and was gratified to see a sliver of the instrument’s history unfold before me.

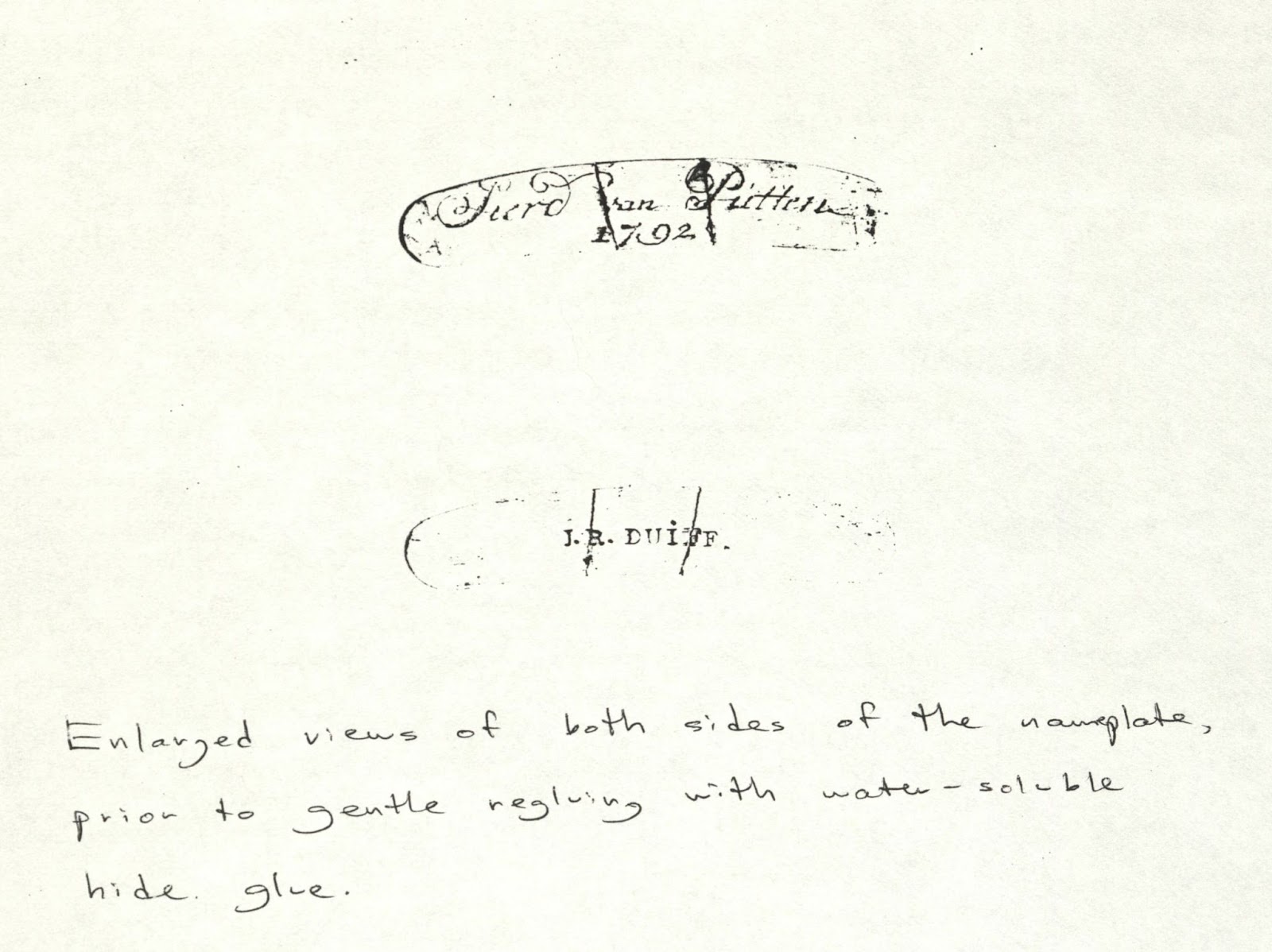

The instrument in question is a large, well-made mahogany-frame octant. It is fairly typical as far as octants from this period go, apart from its beautifully decorated index arm, a feature which isn’t quite as common. Peter purchased the octant from dealers David and Yola Coffeen of Tesseract in 1991. At that time, the ivory nameplate was loose and broken into three pieces. Surprisingly, the nameplate featured not one but two names. On one side, in simple stamped letters is the name “J.R. Duiff” and on the other side, in elaborate hand-engraved script, is the name “Sierd van Putten, 1792.” At the time of the acquisition no one knew who the names represented. Were they makers? Dealers? Owners? Only history knew for sure. For those of you who regularly read my posts, you’ll know there isn’t anything I love more than playing Sherlock Holmes and trying to solve a mystery, and this is certainly a big one!

I was immediately able to remove two possibilities as neither of the names are of known instrument makers or dealers. Pretty confident the names represented owners, I conducted a basic Google search and was immediately rewarded with a possible candidate for Sierd van Putten within the records of the Stadsarchief Amsterdam (the Amsterdam City Archives) and in the Pärnu city customs books (1764–1782) in Estonia’s Rahvusarhiiv (www.ra.ee). With a potential suspect identified, I moved on to the fantastic online resource Delpher (www.delpher.nl), a Dutch newspaper archive, and later the Soundtoll Registers Online (www.soundtoll.nl). Between these three sources, I was able to build a fairly thorough history of voyages made by Sierd van Putten.

Sierd Sijmens [Symens] van Putten was born in Hindeloopen, Friesland, Nederland on July 6, 1758 to merchant ship skipper Symen [Simon] Ruurds van Putten2 and his wife Jaai Sierds. Sierd may have been sailing with his father from a young age, but the first firm evidence we have showing that he followed in his father’s footsteps appears in 17783 when he is identified as the captain of a flute4 named Jonge Jappe. An advertisement for the sale of a 1/32-part ownership5 found in the 1787 edition of Maandelijkse Nederlandsche Mercurius6 provides details of the vessel. Jonge Jappe was built in 1759 and was 138-½ feet long, 33 feet 4 inches wide, and 7 feet 2-½ inches draught. Voyage records show the vessel was typically crewed by 15 to 16 men.

Documents in the Amsterdam City Archives show the vessel was partly owned/managed by Simon, Sierd’s father, as early as 1766. Although I was unable to trace any sailings of Jonge Jappe before 1778, newspapers before that time tended to report the names of ship’s captains, but not the names of the vessels they were sailing in. Taking the 1766 document under consideration, it’s possible Simon was serving as master of Jonge Jappe and passed control of the vessel to his first son when the controlling ownership in a second vessel, t’ Vertrouwen [The Trust], was acquired.

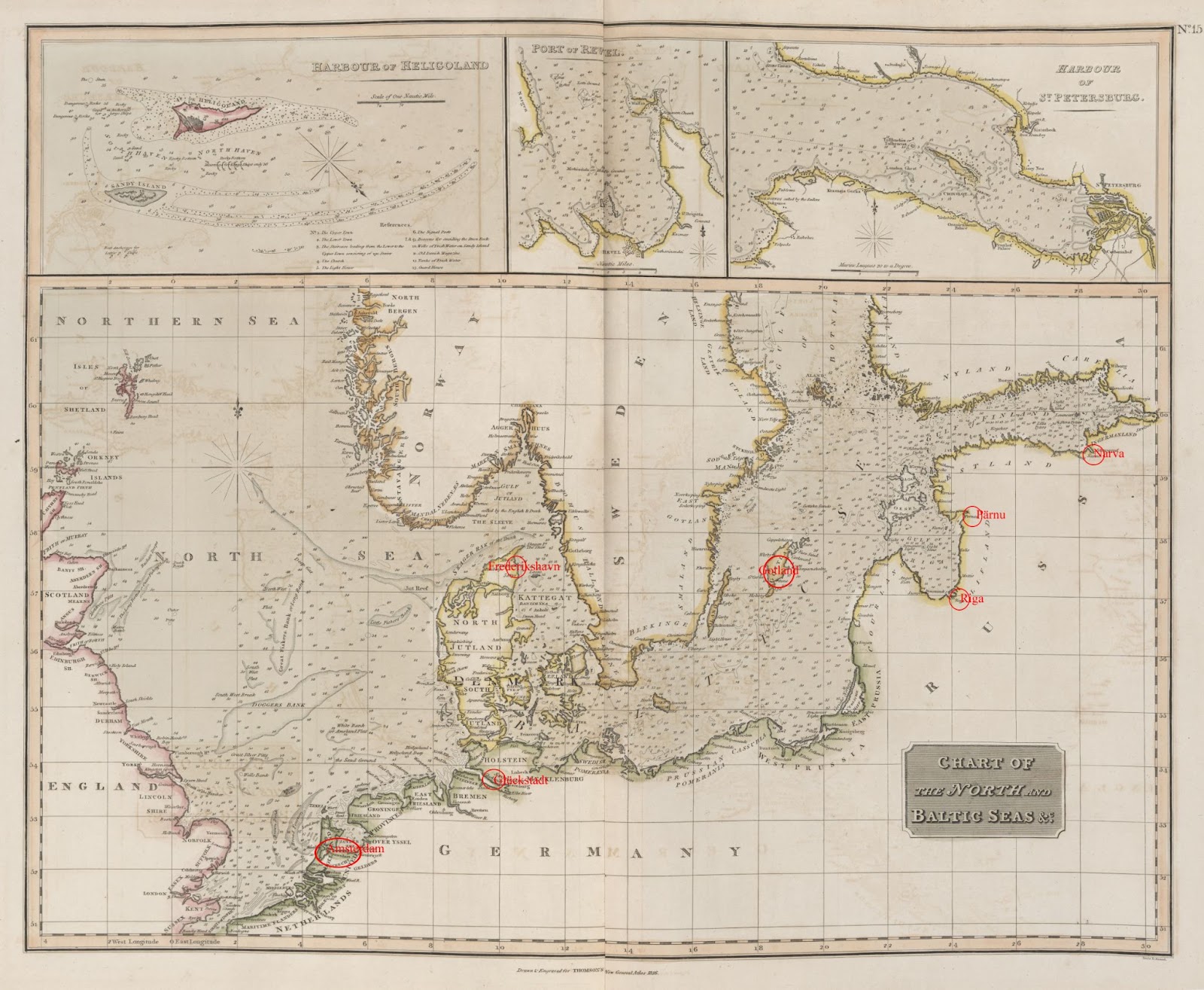

Sierd’s voyages in Jonge Jappe ranged from Amsterdam via the North Sea, through the Skagerrak, Kattegat and the Sound to ports in the Baltic and the Gulfs of Riga and Finland. The ports he visited most often were Narva, Pärnu and Riga in Estonia and Latvia, and Frederikshavn in Denmark. He typically carried general cargo that included lumber, firewood, grains and seeds, wines, cloth, plums, raisins, salt and spices just to name a few. On a 1779 voyage, along with a regular cargo, Jonge Jappe carried a dinghy with a jib and a cargo of flowering plants, rose bushes and seeds.

We start to see evidence that Jonge Jappe is aging by 1784. It was reported on October 18th that Jonge Jappe had lost its topmasts and developed severe hull leaks after sailing into heavy weather on the way to Narva. Sierd sought refuge and conducted temporary repairs on the island of Gotland in the middle of the Baltic Sea. By November 1st, Jonge Jappe was reportedly continuing its voyage. Another ship master reported on December 20th that severe leaking had forced Sierd to sail Jonge Jappe to Copenhagen where more extensive repairs could be completed.

The Van Puttens managed to squeeze eight more years out of Jonge Jappe but shortly after leaving Norway on September 15, 1792, the ship was hit by severe weather and forced into Glückstadt, Germany with a leaky hull. The problem was so severe that the ship had to be unloaded to be repaired. What they found must have been serious because the ship was advertised for sale in Glückstadt on May 2, 1793.

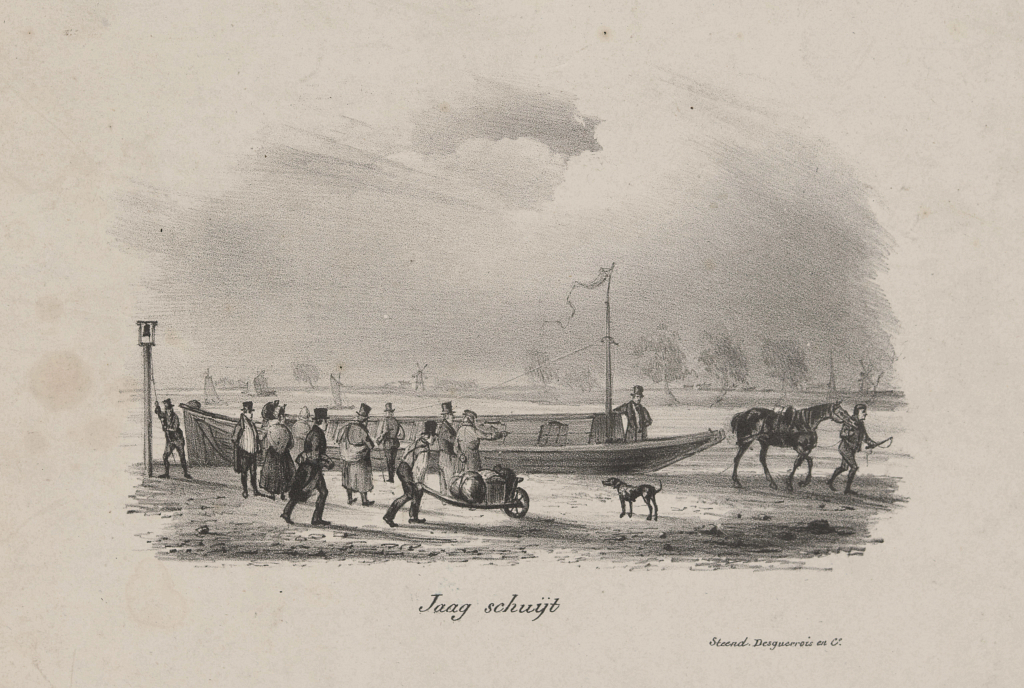

After Jonge Jappe was sold, Sierd became the master of a “trekveer-schip” traveling between Bolsward and Leeuwarden in Friesland, the Netherlands. A trekschuit was a barge carrying passengers and cargo on inland waterways (canals and rivers). While they could be sailed, the masts had to be lowered at every bridge so typically the trekschuit was not sailed but towed by a boy on a horse. Sierd sold his part ownership in the vessel in 1812 and died less than two years later on May 27, 1814, in Amersfoort, Utrecht, Nederland at the age of 55.

As indicated on the nameplate, Sierd van Putten appears to have acquired the octant in 1792. His acquisition of the instrument raises several questions. First, and most importantly, navigating his ship to Scandinavian and Baltic ports wouldn’t have required the use of an octant because land was frequently in sight. Second, where did Mr. van Putten acquire the octant? Colleague Willem Mörzer Bruyns7 says the instrument was made in England and dates closer to 1770 (unfortunately, the maker neglected to put his name on the instrument). As Sierd never seems to have sailed to England, it seems improbable he acquired the octant there. Most likely, by 1792 the octant had made its way to Amsterdam or one of the ports Sierd visited. Or maybe he acquired it from another captain? He wouldn’t have needed it for navigation and its excellent condition suggests the octant was not heavily used at sea. Maybe it was a vanity purchase? After all, wouldn’t every ship captain worth his weight in salt like to have an attractive octant? Heck, that’s why Peter bought his first navigation instrument – as a wall decoration!

This ends the story of owner number one. Octant acquired in 1792… ship sold in 1793… absolutely no history of use uncovered. Sadly, it feels as though my research has raised more questions than it answered although Willem doesn’t necessarily agree.

Identifying the second name on the octant, J. R. Duiff, hasn’t been as straightforward. Since the man’s full name is unknown, I can never be 100% certain I’ve identified the right person. Using Delpher, I did find one possible candidate in 1825 in the form of Jan R. Duiff, a mate on the merchant ship Cornelia Sara. Unfortunately, the article I found was the report of his death on a return voyage from Batavia. The article gives the impression Mr. Duiff was young as he had been married less than a year, and had an infant son that he had probably never seen at the time of his death. As a mate on an East Indiaman, Duiff was in a position that would have required the use of an octant. Another strong connection is that Jan R. Duiff was from Hindeloopen.

Extensive searches in the Sound Toll Registry and Dutch newspapers turned up no ship captains with the initials and the surname spellings of J.R. Duiff, Duif, Duyff, and Duyf. Willem suggested that maybe the initials on the nameplate had been incorrectly stamped. Could “J. R. Duiff” actually be “R. J. Duiff?” If so, there is one strong candidate for that person: Rijndert [Reindert] Jansz Duiff (c. 1766-1848). Like Van Putten, Reindert Jansz Duiff was born in Hindeloopen and was a skipper sailing primarily to Baltic and Scandinavian ports.

I was able to find records of Mr. Duiff in the Sound Toll Registry stretching from 1794 to 1826. While he sailed to many of the same ports as Sierd, some of his later voyages ranged a little farther with sailings to London, Havre-de-Grâce (Le Havre), Brest and Ferrol (Spain). A few of the ships he operated were Peace (around 1802), Concordia (around 1814), Crown Prince of the Netherlands (around 1816-1818), and Hersteller (around 1824-1825). Unfortunately, we’ll never know for sure if this particular Duiff owned the octant, but the consecutive timing of Van Putten’s and Duiff’s careers and a shared hometown certainly is compelling!

At a dead end, I decided to try and gain more insight into the instrument’s history by looking at the decorations on the index arm. I know that octants with decoratively engraved index arms aren’t quite as common as undecorated ones, so I took a look at the 61 octants in our collection and found four others with decorative engraving. Decorations included birds, flags, drums, arrows, quivers, flowers and plant motifs, swags, and geometric shapes. One of the four 1948.0576.000001A had similar decorations to Van Putten’s octant, especially around the vernier window at the base of the index arm. Unlike many other decorated octants, there is a name on 1948.0576.000001A: Willcox & Coysgarne of Hermitage, London. Unfortunately, Willcox & Coysgarne were ship chandlers so they probably were the retailers of the octant not the makers. While we still don’t know who the maker is, I certainly had fun looking at all of the wonderful octants in our Collection.

So, a month or more of research has revealed less than a year of this 253-year-old instrument’s life. If anything, now you understand the obstacles researchers face when trying to rebuild the history of an artifact that suffers from dissociation.

I want to thank colleague Willem Mörzer Bruyns for his advice and assistance in the writing of this post.

Endnotes

1. Peter Ifland was a private collector who amassed a large collection of navigating instruments. In 1998, the Museum published his award-winning book Taking the Stars, Celestial Navigation from Argonauts to Astronauts. Following the book’s publication, Peter donated 169 instruments to The Mariners’ Museum’s Collection. Over the next 20 years, additional donations and supported acquisitions followed, including Peter’s large library. The materials, a significant addition to the Museum’s already strong Collection of navigating and scientific instruments, propelled a great Collection into an extraordinary one.

2. I found Simon skippering voyages between 1745 and 1791. It appears that in 1779 he acquired a flute named ‘t Vertrouwen (The Trust). Upon his retirement in 1791 ‘t Vertrouwen was taken over by his second son, Ruurds Symens van Putten.

3. I found many voyages dated before 1778 but they only reported the name “S. van Putten,” making it difficult to determine if the skipper was Simon or Sierd.

4. The name of this vessel is spelled many different ways. The Aak to Zumbra dictionary of watercraft suggests “fluit” for the standard spelling of the Netherlands bulk-cargo vessel, which is quickly followed by many other recorded names. Fluyt or Flûte seem to be the preferred spellings these days. I’ve stuck with flute because that is the accepted English spelling for the name of the vessel.

5. According to Willem Mörzer Bruyns: In my country, at the time of the Van Puttens until well into the 19th century, ships were not owned by shipping companies as we know them today. The building sum, or the price of a second-hand ship, was called the ‘part’. When a ship was built, or purchased second-hand, individuals, private or in business, could buy a percentage of the ‘part’ and would then be part owner of the vessel. The individual with the largest percentage would represent the others in negotiations and was known as the bookkeeper; the master of the ship was also obliged to purchase a percentage in his ship, becoming part owner. Percentage certificates could be traded through a public notary.

6. De Maandelykse Nederlandsche Mercurius…, from January to June 1787, Bernardus Mourie, Amsterdam, 1787. Volume 27, page 80.

7. Willem Mörzer Bruyns is a Dutch historian of navigational science and retired Senior Curator of Navigation at the Nederlands Scheepvaartmuseum, Amsterdam. In 1995, he was the Huntington Fellow at The Mariners’ Museum, and cataloged the Museum’s collection of navigating and scientific instruments, resulting in the Museum acquiring Peter Ifland’s collection. In 1996 the Museum published Willem’s Elements of Navigation in The Collection of The Mariners Museum.