Last year, in preparation for a Lifelong Learning lecture on literature I re-read one of my favorite fiction series, Dudley Pope’s Lord Ramage series. Pope’s storytelling is a wonderful blend of fiction with historical facts and events. One of my favorite books in the series is Ramage’s Diamond which co-opts the true story of the occupation of Diamond Rock by the British Royal Navy at the beginning of the Napoleonic Wars. The Diamond Rock story is so remarkable I presented the topic during our annual Sips & Trips event on June 24th. Event attendees loved the story and since it was impossible to relay all of the intriguing details in a few talking points I thought a blog post was in order!

It all started in May of 1803 when war reignited between Britain and France. Commodore Samuel Hood (1762-1814), who had the lofty title of ‘Commander-in-chief of His Majesty’s Ships and Vessels in the Windward and Leeward Islands,’ was given the task of helping the army reacquire all of the islands and territories ceded in the 1802 Treaty of Amiens. Within three months, the islands of St. Lucia and Tobago had been retaken and the Dutch colonies of Demerara, Essequibo, and Berbice had been voluntarily turned over to British control.

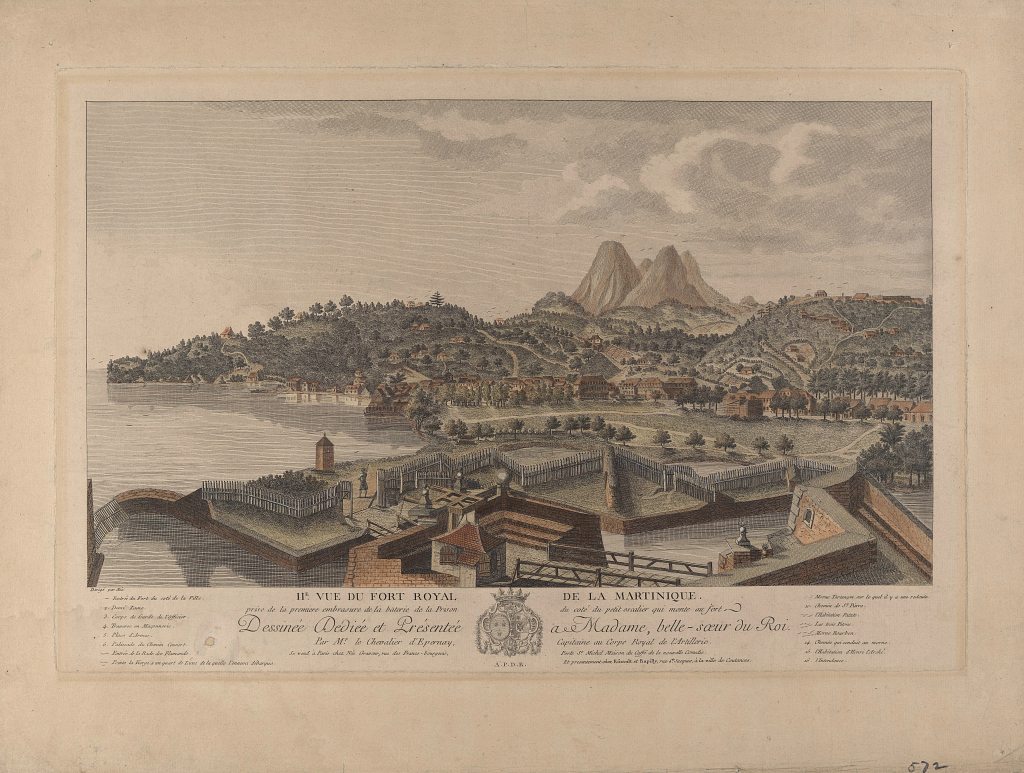

With British control re-established throughout most of his station, Hood’s small squadron began patrolling nearly a thousand miles of islands1 in an effort to limit French activity. The British also established a blockade of France’s principal port in the West Indies: Fort-de-France on the southwestern coast of Martinique. Blockading Fort-de-France’s port was vital for several reasons. First, it curtailed the activities of the numerous privateers that used the port as a base of operations. It also prevented French warships and merchant ships from leaving port and arriving ships from delivering supplies and reinforcements to the garrison stationed on the island.

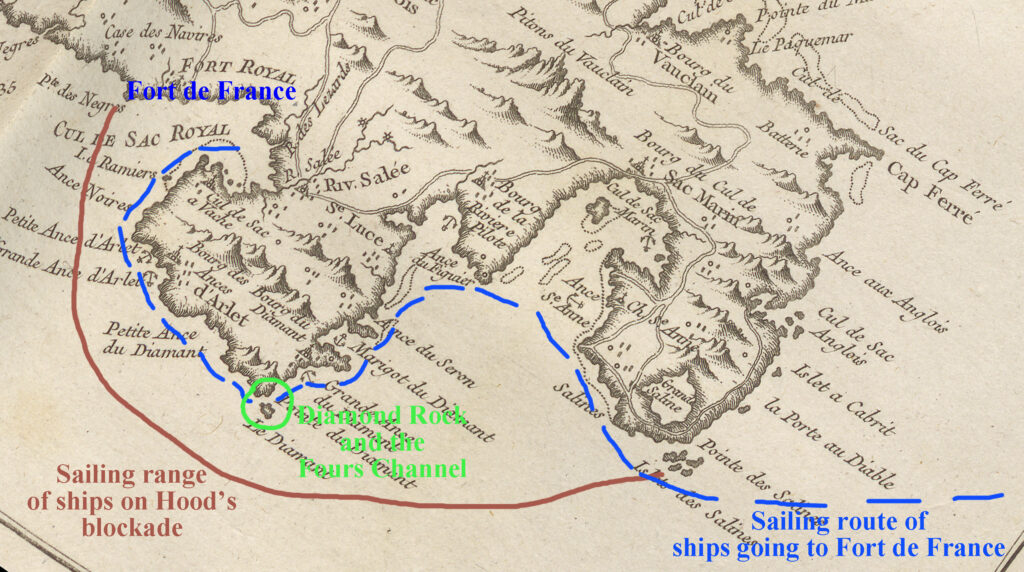

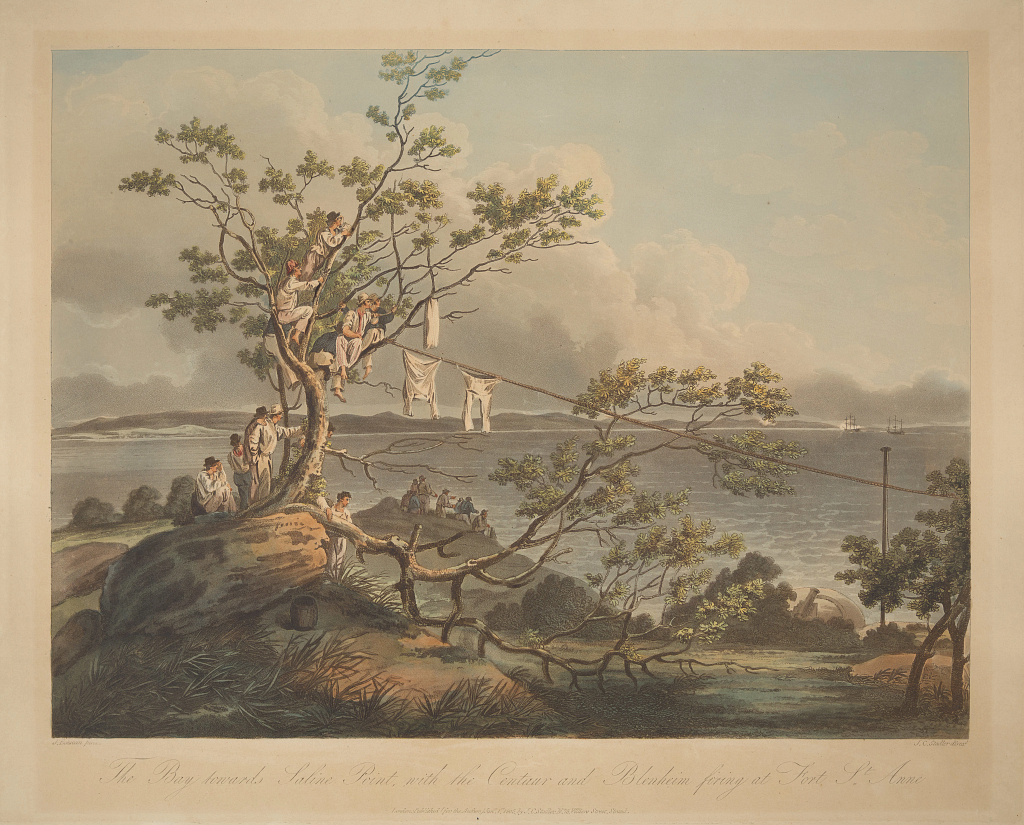

To conduct these tasks, the Admiralty had given Commodore Hood just two 74-gun ships, HMS Centaur and HMS Blenheim, six frigates, and a handful of smaller vessels3. Maintaining a rigid blockade of Fort-de-France required two or three frigates or armed sloops to constantly patrol between Pointe des Salines on the southern coast of Martinique and Pointe de Negres on the north side of Fort Royal Bay. The concentration of so much of Hood’s small force on this one task was stretching his small squadron to the breaking point.

Hood’s Brilliant Idea

While ruminating on his difficult situation, Hood noticed that all of the ships sailing to Fort-de-France invariably followed the same route. Crews approached the island from the south, rounded Pointe des Salines, and then stayed inshore, working the current and anchoring when necessary to prevent the ship from being swept away from the island by the prevailing westerly currents and winds. This route took ships through the mile-wide Fours Channel between the Pointe du Diamant on the mainland and Diamond Rock4, a 574-foot high fang of rock sticking out of the ocean on the southern side of the channel. After passing through the channel, crews turned north and sailed up the coast to the port.

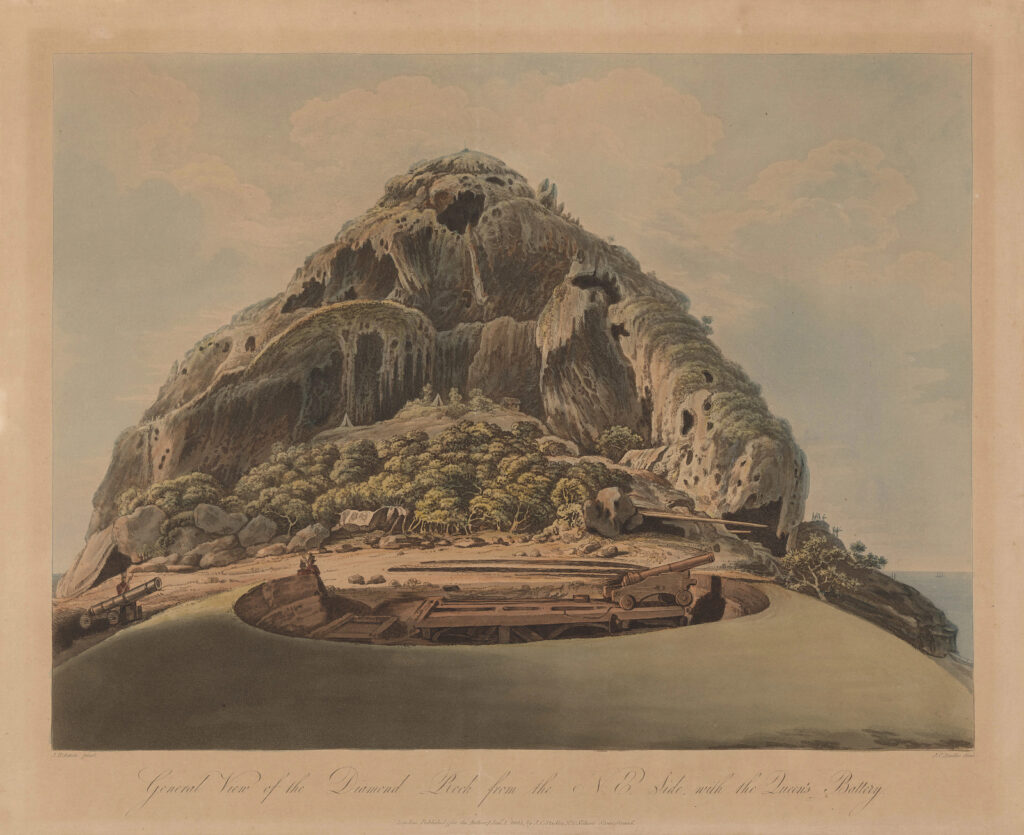

Diamond Rock was so strategically placed that Hood believed that if he could mount guns on its summit and maintain a garrison there, an effective blockade could be maintained without depleting his small fleet. Occupying and fortifying Diamond Rock had other advantages as well. Unlike a ship, it was fairly impregnable and Hood believed it would be relatively easy to defend. He stated in his first official dispatch to the Admiralty, “Thirty riflemen will keep the hill against ten thousand…it is a perfect naval post.”5 Lookouts stationed on the Rock’s summit would be able to see enemy ships approaching as far as 40 miles away and give early warning to the British garrison on St. Lucia. Finally, as an island, Diamond Rock would be immune to the northeast trades, tropical storms, and hurricanes6 that frequently endangered Hood’s ships and drove them off station.

A Formidable, Desolate Place

Despite its alluring name, Diamond Rock is a relatively inhospitable place. The water surrounding the little island is extremely deep, making anchoring close by extremely difficult. Eventually the British found a coral patch about three-quarters of a mile away where the water was just 30 to 42 feet deep, but anchoring in coral can be problematic. The rubbing of the ship’s anchor cable against the sharp coral frequently cut the line, suddenly casting the anchored vessel adrift.

Diamond Rock has perpendicular cliffs and numerous overhanging, bat-filled caves7 on its south, southwest, eastern, and western sides. The only available landing spot is on the northwest side, where a narrow, slippery, seaweed-covered ledge projects into the sea. Even in calm weather, waves crash against the ledge making landing a treacherous and dangerous operation. Only in a well-handled boat and with expert timing can someone successfully land on the island.

One of the first things the British discovered after landing is that sturdy shoes are a necessity. The jagged, basalt surface of the Rock is sharp and “cuts like flint.”8 The tall grasses growing in the crevices of the Rock’s fractured surface hide prickly cactus and, at least in the early 19th century, an abundance of lizards and snakes, one of which was deadly9, from view. The men living on the island didn’t even know they had tread on snakes or cacti until they suddenly found themselves injured.

The island’s biggest problems are the intense heat and lack of freshwater. During the day, the exposed rock absorbs so much heat it becomes untouchable. During the British fortification effort, the men, tools, and even the Rock itself had to be continually doused with seawater to cool things down. The heat reflecting off the Rock was so intense even the hardiest man couldn’t work for more than an hour without needing a break and a constant supply of drinking water, which would have to be supplied by passing frigates or collected by boats in St. Lucia. Firewood for cooking, food, gunpowder, and ammunition would have to be supplied the same way.

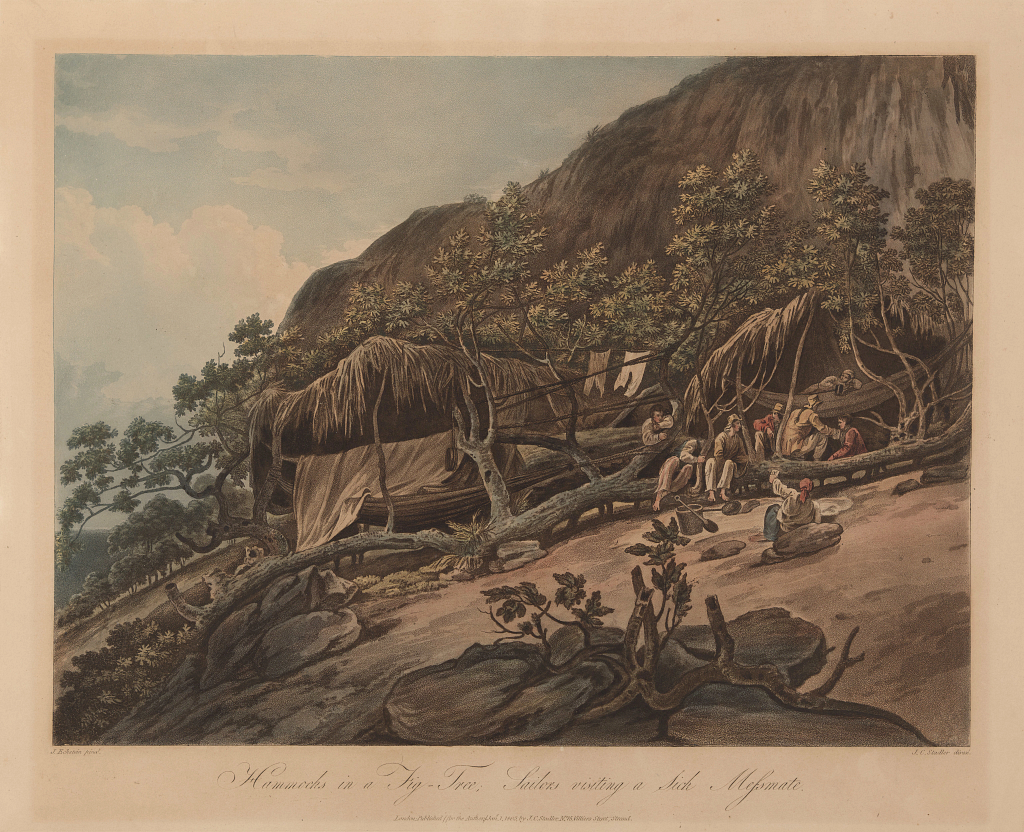

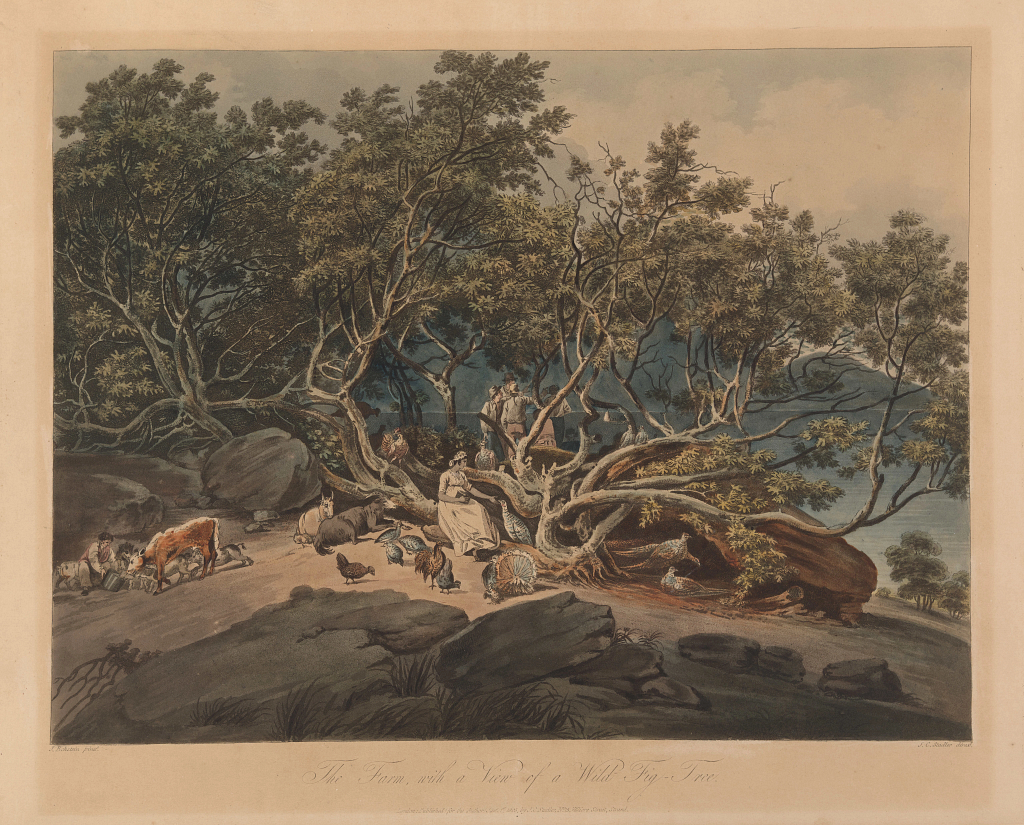

Despite these drawbacks, the British sailors living on Diamond Rock found it to be an enjoyable and healthy place to live. So healthy, in fact, that the British closed their hospital on Barbados and moved the patients to Diamond Rock. The island’s large dry caves and groves of fig trees provided such a welcome respite from the difficult conditions of shipboard life that some captains used the Rock to give their sailors shore leave. Once there, the vacationing sailors didn’t want to leave. According to John Eckstein, an artist who stayed on the island during the initial fortification efforts, “The seamen call their coming here going ashore; and so powerful is this liberty…that they return to the ship with reluctance, though…while here, [were] deprived of every comfort and allowance. Here they will work twice as hard, and conceal their being ill, and even die without help, rather than leave the barren rock to return on board.”

The Occupation and Fortification Efforts Begin

On January 7, 1804, Hood landed 50 seamen and 25 marines under the command of 1st Lieutenant James Maurice to begin the enormous task of fortifying the island and making it livable. With men on the island, Hood took steps to prevent the French from attacking or interfering with the British fortification efforts. He sent a raiding party from HMS Blenheim to destroy a French gun battery being erected on the coastline opposite Diamond Rock. Hood also sent a raiding party into the Banc du Fort-Saint-Louis to cut out the one French warship sheltering there (the 16-gun brig or corvette Le Curieux). Both missions were successful.

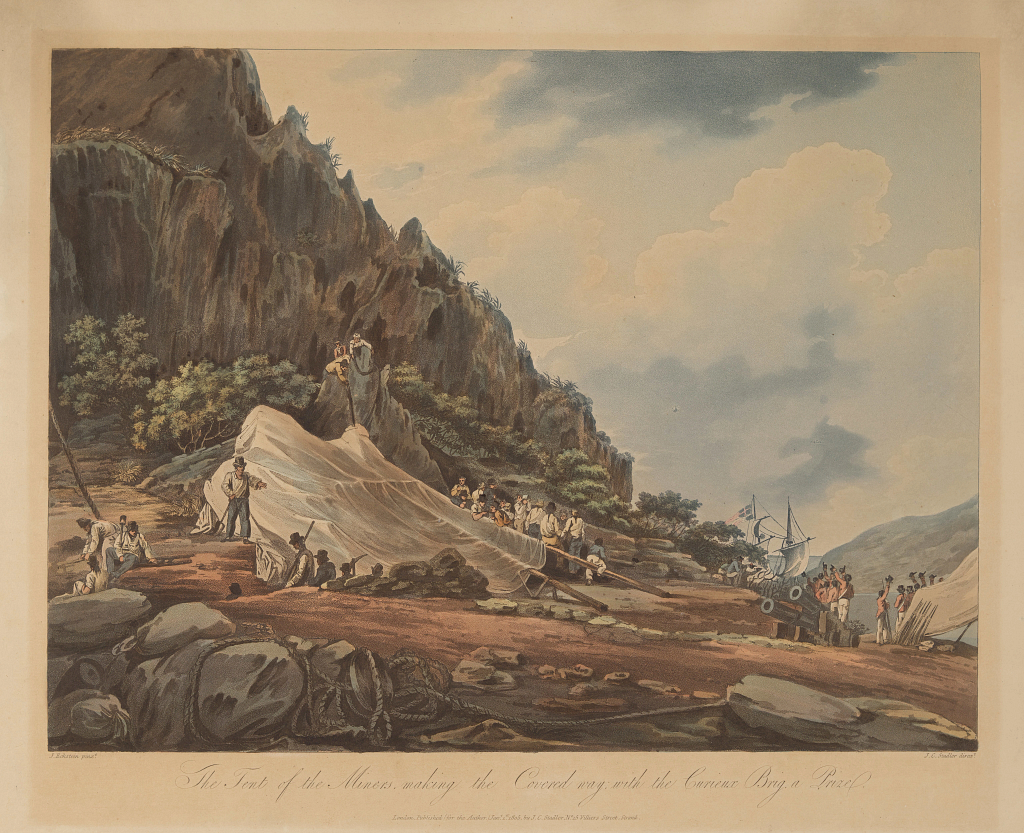

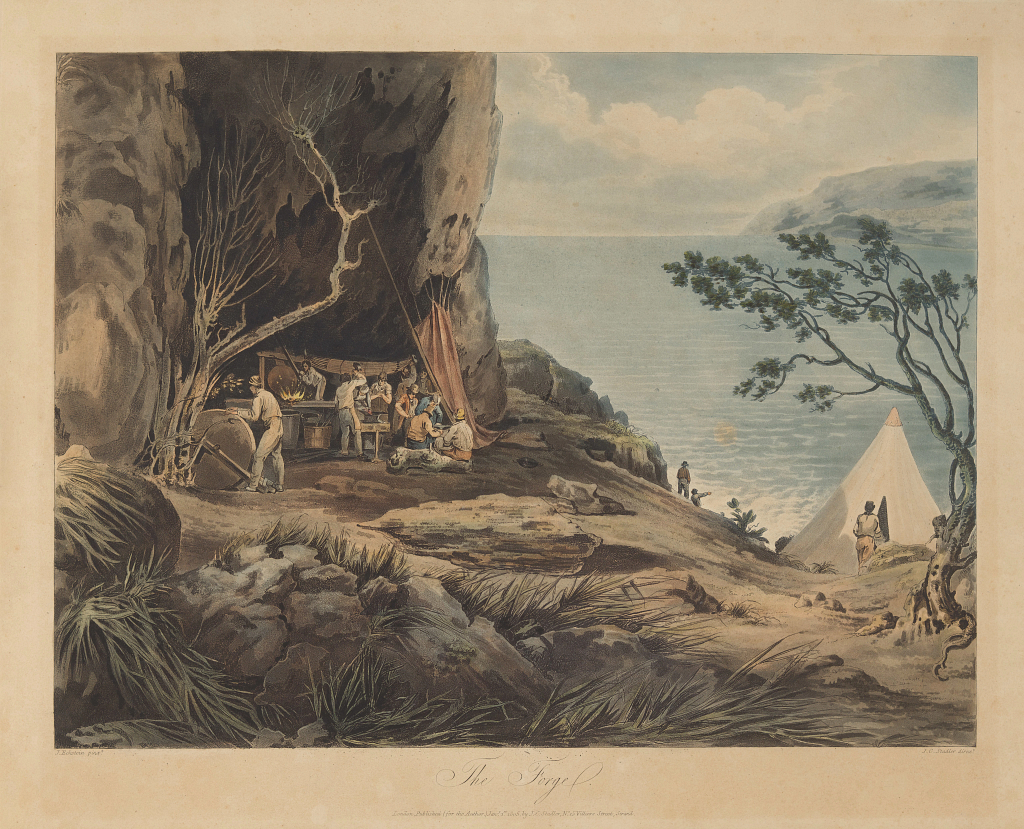

Blacksmiths, stone masons, military sappers and miners were sent from St. Lucia to support HMS Centaur’s seamen, carpenters, sailmakers and gunners. They set up forges and other work areas, blasted out rock, and installed gun platforms and ramparts. They built a 3,000-gallon cistern to hold water. They blasted out a rock wall and built a stone parapet to protect a passageway 400 feet long and 15 feet wide from the sea. Called the “Covered Way,” the passageway provided access to several sleeping caves and established a communication pathway between three gun batteries installed at the base of the island.

The men replaced a temporary slipway installed to facilitate the initial landing with a larger, heavier platform that was constructed and hauled onto the landing ledge by a hundred seamen. A pair of davits were installed next to it so boats could be lifted out of the water in rough conditions. The many caves on the island were cleared of bats and birds, and the men shoveled out tons of guano to install living and working quarters and storage areas for provisions and ammunition.

Moving around the many perpendicular surfaces of the island and climbing to the summit was extremely difficult and hazardous. To facilitate movement up and down the Rock, the men installed a system of safety lines and rope ladders at the most difficult points10. Even with these aids, it remained a hair-raising twenty minute climb to the summit. A jackstay used to hoist a cannon into one of the upper caves was repurposed into a makeshift elevator dubbed the “Mail Coach” by the men. It was used to hoist stores, and sometimes men, to an upper cave that served as the main storage area for the garrison.

Commissioning HMS Diamond Rock

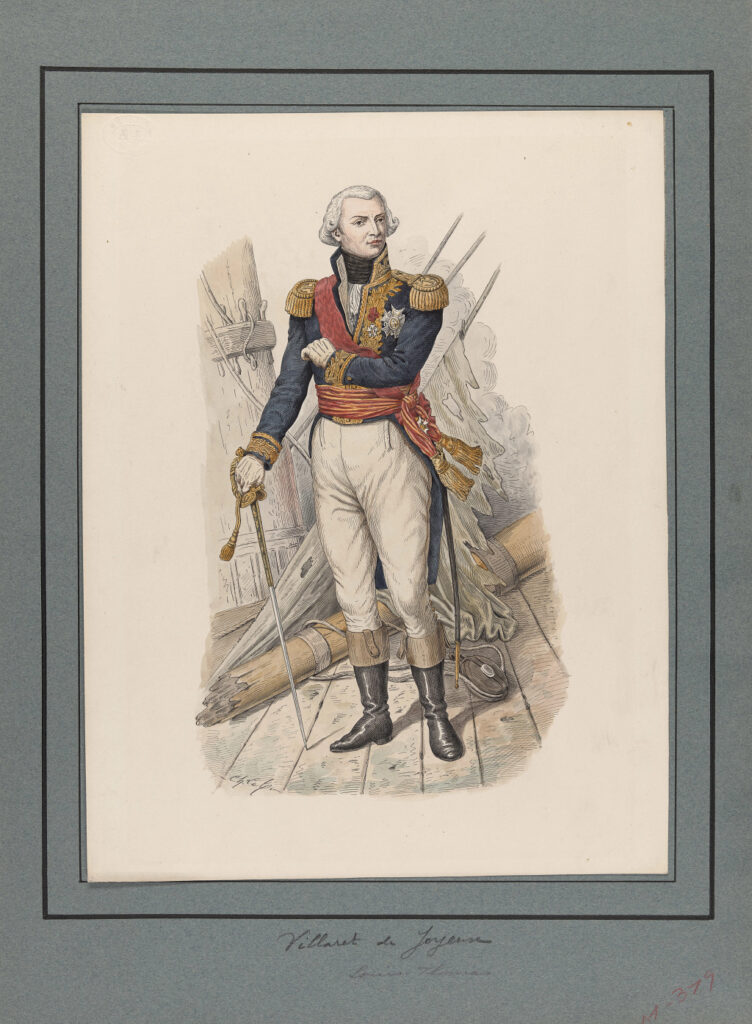

On January 10th, 1804, the British officially laid claim to the island with a formal flag-raising ceremony that was carefully watched by a large crowd of French observers on Martinique. The island’s French governor, the fantastically named Captain-General Louis Thomas Villaret de Joyeuse, initially mocked the British effort as an “act of braggadocio.” He also said that Hood was stupid for “wasting money, time and effort on a worthless rock,” but once activated, the British blockading rock proved to be a great irritation and constant humiliation to Joyeuse and the naval administration in France.

On February 3rd, Diamond Rock was commissioned into the Royal Navy with Lieutenant James Maurice serving as commander of a garrison of 120 men and boys. Initially, to circumvent the bureaucratic technicalities of manning an island as a captured enemy ship, Diamond Rock was treated as an appendage of a sloop that had been captured from the French and stationed at the island. Originally named Fort Diamond, the sloop was later renamed HMS Diamond Rock by the Admiralty. In reality, this setup was just a technicality as the sloop was later recaptured by the French, and the British replaced it with another vessel without having any effect on the Rock’s status. In time, the bureaucratic technicalities were forgotten, and the island itself became HM Sloop-of-War Diamond Rock.

Mounting Guns on Diamond Rock

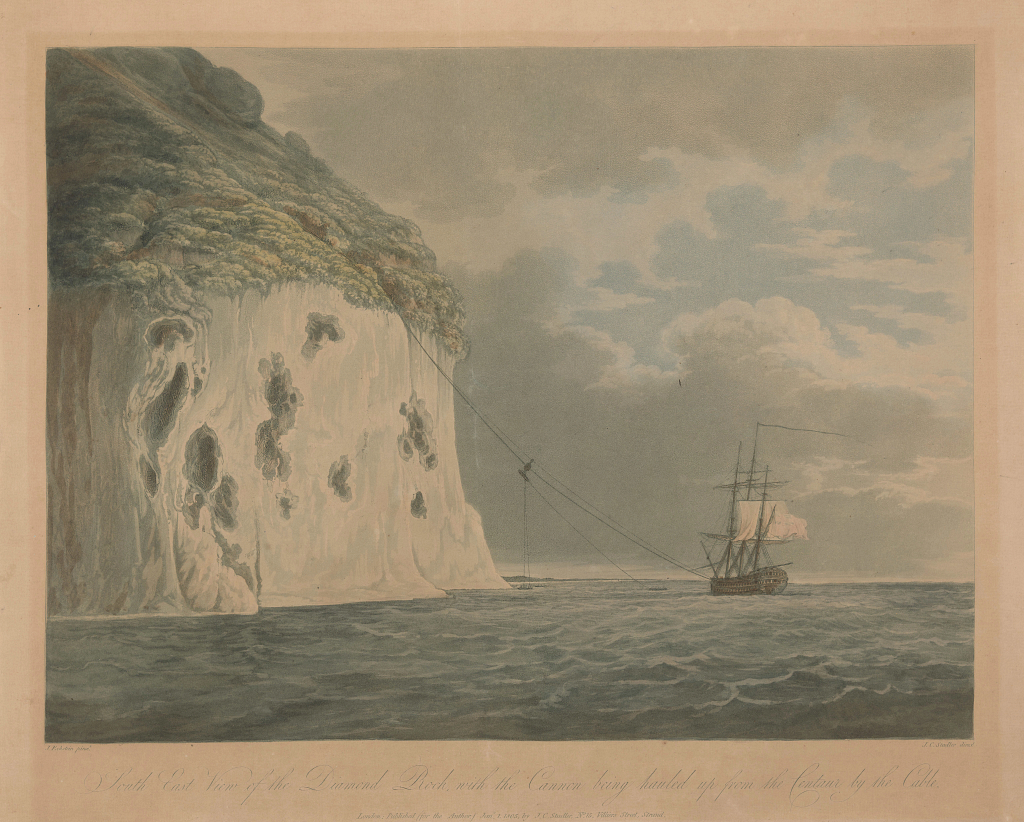

Getting the guns into position, especially those on the summit, was an absolutely superb feat of engineering. It began on January 15th when one of HMS Centaur’s 24-pound long guns, weighing over two tons, was hoisted off the ship with a block and tackle hanging from the end of the main yard. The gun was swayed over the bulwark and lowered into a cradle of spars and planks erected on a 40-foot launch. The gun was then balanced and lashed down. Sailors rowed the launch while a second launch towed it to the Rock’s newly enlarged landing stage. The launch was maneuvered broadside-to the landing stage, and heavy cables were attached to the gun’s lashings so the men on shore could haul the boat further in. Once over the submerged apron of the landing stage, the cannon was shoved overboard into the surf. At that point, the sheer brute force of 50 or more men hauled the two-ton cannon out of the sea and up the ramp to a sheerlegs where it was lifted back onto its carriage. The process was later repeated with a second gun.

Within two days, the men on the island had moved the massive cannons from the landing stage to gun placements situated on the lower levels of Diamond Rock. The gun in the Queen’s Battery was mounted on a timber traverse with its muzzle pointing north across Fours Channel. The gun in Centaur’s Battery faced northeast to cover the seaward approaches to the channel.

Within a few weeks, the garrison had contrived a way to sway the 24-pound cannon in Queen’s Battery into a deep cave an incredible 230 feet up the Rock’s northerly face. The new gun placement, called Hood’s Battery, covered the Fours Channel. With its position hundreds of feet up the cliff face, the cave was safe from enemy attack, so it also served as the island’s principle magazine and storage area.

To defend the landing place, conduct blockading duties like chasing and stopping vessels, and to acquire supplies from St. Lucia, the garrison was given a 36-foot launch armed with a carronade, three 14-oared cutters, and a dinghy. Additional fortification efforts happened later in the year when several nine-pound cannons were installed to create two additional batteries on the lower level of the island (called Maurice’s and the hospital battery). The two 24-pound cannons loaned from HMS Centaur and installed in Centaur’s and Hood’s batteries were also swapped out for 18-pound cannons and a 32-pound carronade, which was installed in Hood’s battery.

An Engineering Feat of Massive Proportions

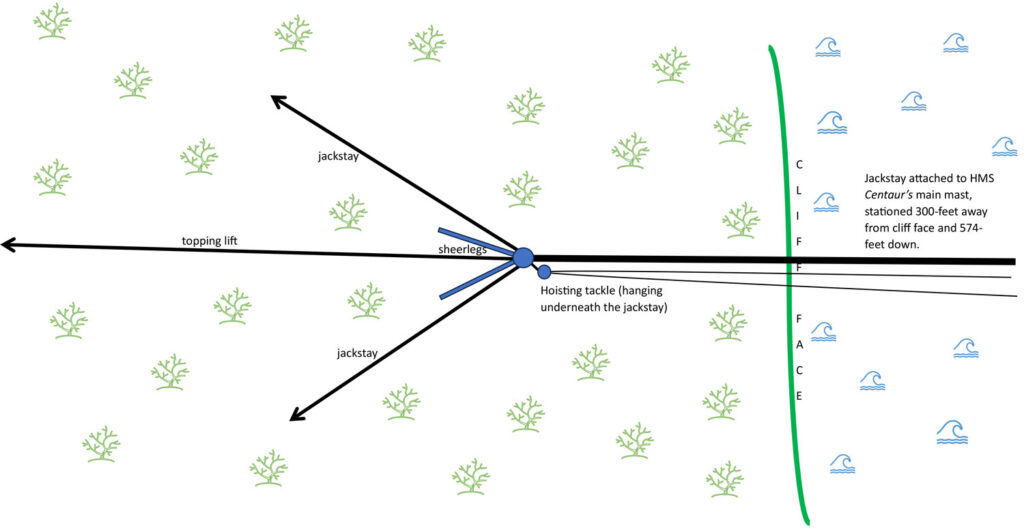

Although it had been used on a much smaller scale, Hood was confident that the method used to install the cannon in Hood’s Battery could be used to install two 18-pound long guns on the 574-foot high summit of Diamond Rock. In preparation for the lift, anchors were driven deep into the rock on the island’s southwestern face. The anchors were used to secure several small jackstays and a topping lift to a set of sheerlegs on the slope above the cliff. The jackstays were probably set at angles to the sheerlegs to prevent them from swaying from side to side, while the topping lift was positioned in-line with the hoisting tackle to provide stabilization and support.

An 8” hawser was hauled up to the top of the cliff and set up as a jackstay running between the top of the sheerlegs and the mainmast of HMS Centaur. Underneath the jackstay, the British rigged a hoisting tackle, a continuous loop of rope they would use to haul the cannon up the jackstay (for you non-sailors like me, this sort of works like one of those circular clotheslines you see stretched between buildings in big cities). A large block called a viol was hung on the jackstay to serve as a traveller.

On the day of the lift, HMS Centaur anchored fore-and-aft in deep water a mere 300 feet from the base of the cliff. After retrieving and attaching the jackstay to the mast and the hoisting tackle to the capstan, an 18-pound cannon hung vertically in a gun sling was shackled to the traveller. Sailors used the capstan and hard work to move the cannon up the jackstay. The gun had to be hauled nearly 600 feet up from sea level and 400 feet horizontally to reach the sheerlegs. The lift took about seven hours because the hoisting tackle, sling, and gun frequently became caught in the overhangs of the rock. To pry it loose, Lt. Maurice hung men with pry bars in improvised bosun’s chairs on the slope above and over the edge of the cliff. When the cannon finally reached the top of the cable, the exhausted men swung it onto a secure ledge and lashed it in place for the night.

The following day, 50 men working in relays used brute force to haul the gun up to the summit. Its carriage, ammunition, and other supplies were hauled to the new gun placement, called the Diamond Battery, the same way. The second 18-pounder was hoisted up to the summit on February 24th. Thanks to the lessons learned during the first lift (the cannon was hung horizontally instead of vertically), it took half the time.

Daily Life on Diamond Rock

Once the basic fortification work was complete, the garrison was provisioned with enough salt tack and biscuit to feed 120 men and boys (and apparently a few women!) for four months. These stores were supplemented by Martinique’s native inhabitants, who periodically sailed over to the island at night to sell fish, turtle meat, and melons. They also provided intelligence about French shipping and troop movements, which the garrison passed on to the ships in Hood’s squadron. The island itself provided food in the form of a wild spinach that the sailors gathered and boiled. It was said to be very delicious and had the added benefit of preventing scurvy. Looking at John Eckstein’s images, the garrison also maintained a small farm of animals and birds for eggs, milk, and meat. As I mentioned earlier, drinking water was a constant concern for the garrison.

Every nook and cranny capable of providing shelter was slung with hammocks for sleeping. Men sheltered in the caves when not on duty to keep out of the punishing sun and during rainstorms. Some of the officers, including Commander Maurice and the visiting artist, John Eckstein, slept in tents pitched on whatever level ground was available. Eckstein described his living quarters as, “Our little…tents spread their canvas on cross sticks, and are barricaded with stones…[we] retire upon the dried grass…rolled in blankets…Every morning, on waking, I behold the sea apparently close to my feet; for they reach out of my tent, only three good yards from where the rock descends about two hundred feet into the sea.”

Maintaining the Blockade and the French Response

Of course, the whole reason the British fortified Diamond Rock was to blockade Fort-de-France.

During the seventeen months the British held the island, an untold number of French ships and coastal craft from various nations were stopped when they tried to pass Diamond Rock. As soon as a ship was sighted, a shot was placed across its bow. If it failed to stop, one of the garrison’s boats gave chase, boarded, and searched the vessel. Foreign ships carrying supplies to Fort-de-France were turned away and warned they would be sunk or taken as prize if the order was disobeyed. French-flagged vessels with contraband materials on board were escorted to St. Lucia and impounded.

Shortly after HMS Centaur left the area, the French on Martinique began organizing an attack. One night in May 1804, four boatloads of soldiers attempted to row across the Fours Channel and attack Diamond Rock. Unable to resist the strong current, the boats were swept past the Rock and out to sea. The garrison only learned of the attempt after they stopped an American ship and were told it had picked up a boatload of half-dead French soldiers far out at sea and had returned them to Petit Anse d’Arlet. After that disaster, the French on Martinique gave up all attempts to dislodge the British and appealed to France for assistance.

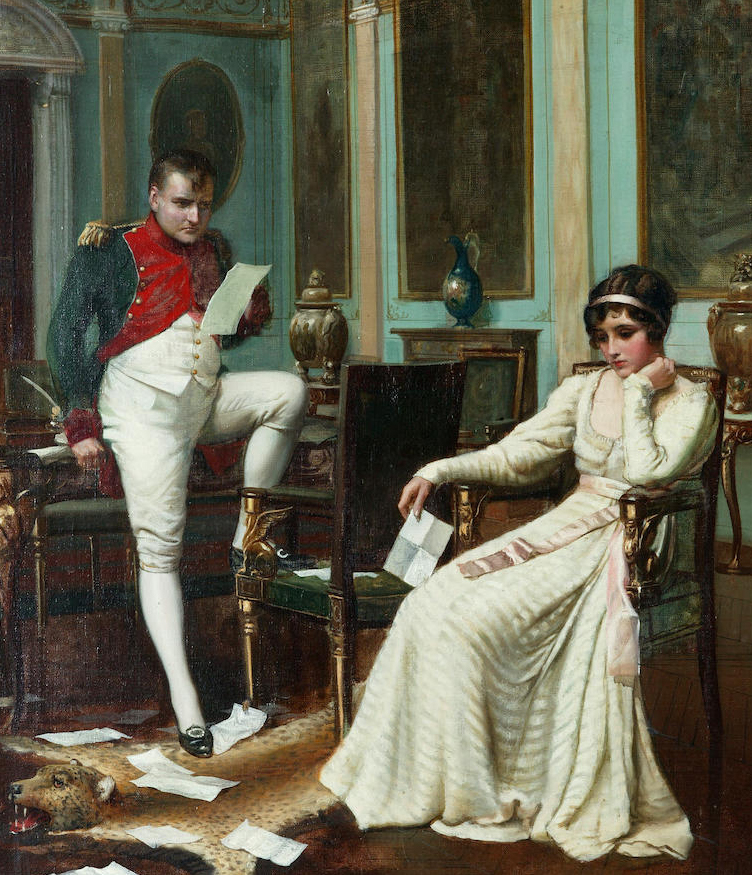

Napoleon’s Grand Plan

By late 1804, Napoleon’s simmering anger about the British occupation of Diamond Rock had developed into an all-consuming obsession. Besides the sheer embarrassment of it, his wife, Josephine, who had been born and raised on Martinique, was having trouble communicating with her mother. She was also having trouble acquiring plants for her greenhouses and birds for her aviary at Château de Malmaison. Napoleon had another reason for removing the British from Diamond Rock – the West Indies, and Martinique in particular, played an important role in his plan to invade England.

Shortly after the resumption of the war, Napoleon began developing plans for the invasion of England. He ordered French shipyards along the English Channel to build vessels capable of transporting troops and armament to England. Fully aware of Napoleon’s plan, the Royal Navy stationed ships near every French port. Planning to launch his invasion some time in the summer of 1805, Napoleon knew he needed a large concentration of naval ships to protect the flotilla of troop ships as they crossed the Channel, so he developed his “Grand Plan.”

Napoleon’s plan called for several French fleets and one Spanish one to escape their blockaded ports, sail to the Caribbean, and wreak havoc among the British-held islands to draw the British ships away from their stations (including Horatio Nelson in the Mediterranean). Once the British had sailed for the Caribbean, the French and Spanish fleets would double back to Boulogne to guard the invasion craft as they crossed the Channel11

Napoleon tried to set the plan in motion in December 1804 by ordering Vice Admiral de Missiessy in Rochefort and Vice Admiral Villeneuve in Toulon to seize the first opportunity and escape from port. They were to sail to the West Indies, rendezvous at Fort-de-France, capture as many British-held islands as possible, kick the British off Diamond Rock, and then after 60 days, return to Rochefort.

Missiessy managed to escape from Rochefort during a massive snowstorm on January 11, 1805. Villeneuve left Toulon on January 17th, but turned around and went back when bad weather revealed his ships (and men) were completely unseaworthy. Missiessy’s squadron of 11 warships and transports holding 3,500 troops reached Martinique on February 20, 1805. He had been well-briefed about the danger presented by the British on Diamond Rock, so the squadron gave the island a wide berth and entered the port of Fort-de-France to land several hundred sick men and take on supplies.

Despite entreaties from Captain-General Villeret de Joyeuse, to whom the occupation of the Rock had been the source of intense annoyance and bitter humiliation for over a year, Missiessy sailed from Fort de France to make raids on other British held islands. After six weeks, Missiessy returned to Europe without completing any of the tasks Napoleon had set before him – including waiting for the arrival of Villeneuve. Needless to say, Napoleon was infuriated.

Villeneuve’s squadron finally escaped from Toulon on March 30th, 1805, and reached Cadiz on April 9th to pick up a Spanish fleet under Admiral Gravina before sailing to Martinique. The combined fleet reached Fort-de-France on May 14th with 18 ships-of-the-line, seven frigates, three corvettes, one brig, and 4,500 French and Spanish troops and 19,000 seamen. Unlike Missiessy, Villeneuve was not about to disobey Napoleon’s orders.

The French Capture of Diamond Rock

A few days after the arrival of Villeneuve’s fleet, the British garrison engaged a straggling Spanish warship unaware of the danger presented by Diamond Rock. Within an hour of the engagement, the British discovered the heavy firing of their guns had dislodged a section of mortar in the cistern and most of their water supply had been lost12. A search of the island revealed a few barrels of water, but most of it had turned foul and was unfit to drink. Even with strict rationing, the British had less than two weeks of water remaining.

The same afternoon, a French brig left Fort-de-France and began cruising off Diamond Rock alerting the British garrison that an attack was forthcoming. Between May 16th and 29th, while Villeneuve planned his assault, the British found their roles had reversed and they were the ones being blockaded. Realistically, the French could have simply waited until the English ran out of food and water, but Villeneuve was scared. He knew Horatio Nelson’s Mediterranean fleet was headed in his direction and he wanted to leave the West Indies as fast as possible.

As the British prepared for the attack Commander Maurice realized it would be impossible to defend the Rock’s lower cannon placements and moved most of the men, the convalescents in the hospital, and supplies to caves higher up on the island. This move proved prophetic as the intense French gunfire hurled rocks large enough to kill or maim down onto the lower caves and batteries. Many of the French troops who sought shelter in the lower caves after landing were injured or killed by rocks dislodged by friendly fire.

Finally, on May 31st, the wait was over. A French assault force of two 74-gun ships, a frigate, brig, and schooner opened fire on the island. Maurice gave the order to abandon the Queen and Centaur batteries, leaving one man to fire each gun at any target that came within range before retreating to the upper batteries. As the men climbed up the Rock, they cut away or raised the rope ladders and other climbing aids, including the Mail Coach jackstay, to hinder the movement of French troops after they landed. The men in the Hood and Diamond batteries returned fire and managed to inflict some damage, but eventually the French 74s moved so close to the base of the Rock that the summit guns were no longer effective.

As they closed on the island, the British poured murderous cannon and musket fire into the 11 armed and troop-laden longboats and cutters. The men in Hood’s battery managed to sink two while two more were dashed to pieces against the rocks by waves. Thanks to months and months of practice, 108 expert British marksmen (20 marines and 88 men and boys) killed so many men in the leading boats, the survivors threw themselves overboard leaving two more boats filled with dead and dying men drifting out to sea.

By mid-afternoon, about 200 French and Spanish soldiers had landed on the island and taken cover in the lower caves. Many were wounded. Covered by intense fire from the ships, the French continued landing troops and supplies after nightfall, but again, many of the men arrived wounded thanks to the British defense. Besides musket fire, the British were dropping cannonballs and casks full of stones onto the heads of the landing French troops.

After three days and two nights of constant and intense action, the British began running out of ammunition. As for the water situation, the ration had been reduced to one pint of water per man per day. The human body requires 2-1/2 pints of liquid each day to survive, and with the intense heat and activity occurring on the summit, a man could sweat that much in just one hour. With their water supply nearly depleted the men were suffering acutely from dehydration and fatigue. Some were so weak they could barely lift their muskets, and reloading was quickly becoming physically impossible.

Late on the afternoon of June 2nd, knowing a full-scale assault his men couldn’t repel was coming, Maurice sent down a flag of truce and requested a surrender. Articles of capitulation were drawn up and agreed to, and the French took over the batteries and magazines and provided water and food to the British. At sunrise the following morning, the British descended the rock with full military honors and were embarked as prisoners-of-war on the French ships Pluton and Berwick. The following day, Nelson’s squadron arrived in Carlisle Bay, Barbados.

French casualties in the assault are estimated at 50 to 100 killed and over 300 wounded. British casualties were two killed and one wounded. Despite the inevitable French bragging that occurred afterwards, it had taken 3,000 French and Spanish sailors and soldiers (560 of which were landed on the Rock) and 222 cannons on five vessels (including two ships-of-the-line and excluding the brass cannons on the longboats) to defeat 76 British seamen, 12 boys and 20 marines armed with muskets, two cannons and a carronade. That doesn’t sound like something worth boasting about does it? That’s okay, just a few months later, Nelson decimated Villeneuve’s combined fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar.

As for HMS Diamond Rock, the amazing story of its fortification and occupation remains one of the great feats of the Royal Navy in the Napoleonic War. Even today, ships passing Diamond Rock continue to honor the intrepid British sailors who held the island against all odds by dipping their flag in salute.

Footnotes

- Hood’s patrol area stretched from Trinidad to the Virgin Islands.

- When founded, the town was called Fort Royal. The name was briefly changed to Fort de La Republique in the French Revolution, but by the early 19th century the French had settled on the name Fort-de-France.

- The stinginess of the Admiralty was due to the fact that the rest of the Royal Navy was actively blockading every port in France as well as her colonies and overseas stations. This kept the Royal Navy stretched pretty thin, so Hood knew he couldn’t expect any additional ships.

- Diamond Rock is a lava tube, the only visible remnant of an ancient volcano. It got its name because when the sun strikes its salt-encrusted surface from a certain angle, the island sparkles like a gemstone.

- W. B. Rowbotham, “British Occupation of the Diamond Rock, 1804-1805”, Journal of Royal United Service Institution, Volume 101, No. 603, Issue No. 603, page 398.

- This wasn’t wholly true, on September 2, 1804, a hurricane struck Diamond Rock, and although the Rock wasn’t “blown off station”, wind-driven salt water spray spoiled the water in their cistern and soaked half the contents of their powder magazine. Replacing the water was easy. Replacing their damaged powder was not.

- So many bats called the island’s caves home that sailing downwind of the Rock revealed the nauseating stench of the tons of guano that filled the island’s caves.

- This is according to John Eckstein, an artist living on the Rock during the initial fortification efforts. His commentary was published in The Naval Chronicle for 1805.

- Diamond Rock is considered the final home of a critically endangered serpent called Lacépède’s ground snake or the Martinique groundsnake (Erythrolamprus cursor). The last reliable sighting of this snake was in 1968 so scientists have recently wondered if the species is extinct.

- Aware that a French attack was inevitable, permanent climbing aids, like steps, were prohibited. Only temporary climbing aids, like rope ladders and other simple systems, things that could be quickly raised or cut away during an attack, were installed.

- Yeah…um…no chance of this going wrong….

- When the British inspected the tank, they found a large crack crossing the tank’s foundation. Apparently, an earthquake — Commander Maurice had noted the occurrence of a number of small earthquakes in his log — had started the crack, and the intense gunfire that morning had completed the damage.

Interested in learning more? Read His Majesty’s Sloop-of-War Diamond Rock by Vivian Stuart & George T. Eggleston, Robert Hale Limited, London, 1978.