This post is taking a break from the ever-excellent conservation efforts to talk about another important facet of the Monitor Center’s job. Don’t get me wrong; we love the artifacts. Not only are they super cool, but they also connect us to the people who served on board the ship. When we recover a spoon, or a button, or even engine components; we are the first people handling and caring for these artifacts since 1862. We are stewards of the crewmember’s stories.

In honor of African American History Month, I want share the stories of the African Americans who served onboard Monitor.

But first, a (very) brief background into the legislation that made their inclusion possible:

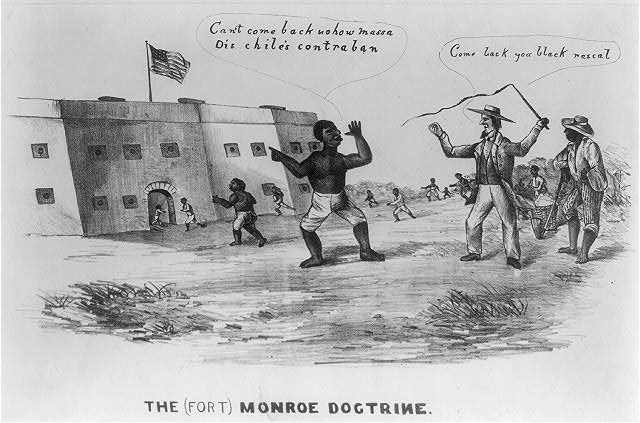

At the outbreak of the Civil War, many enslaved African Americans wanted to join the Union armed forces. (Can you blame them?) However, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 stated that slave owners could request the return of their “property”.

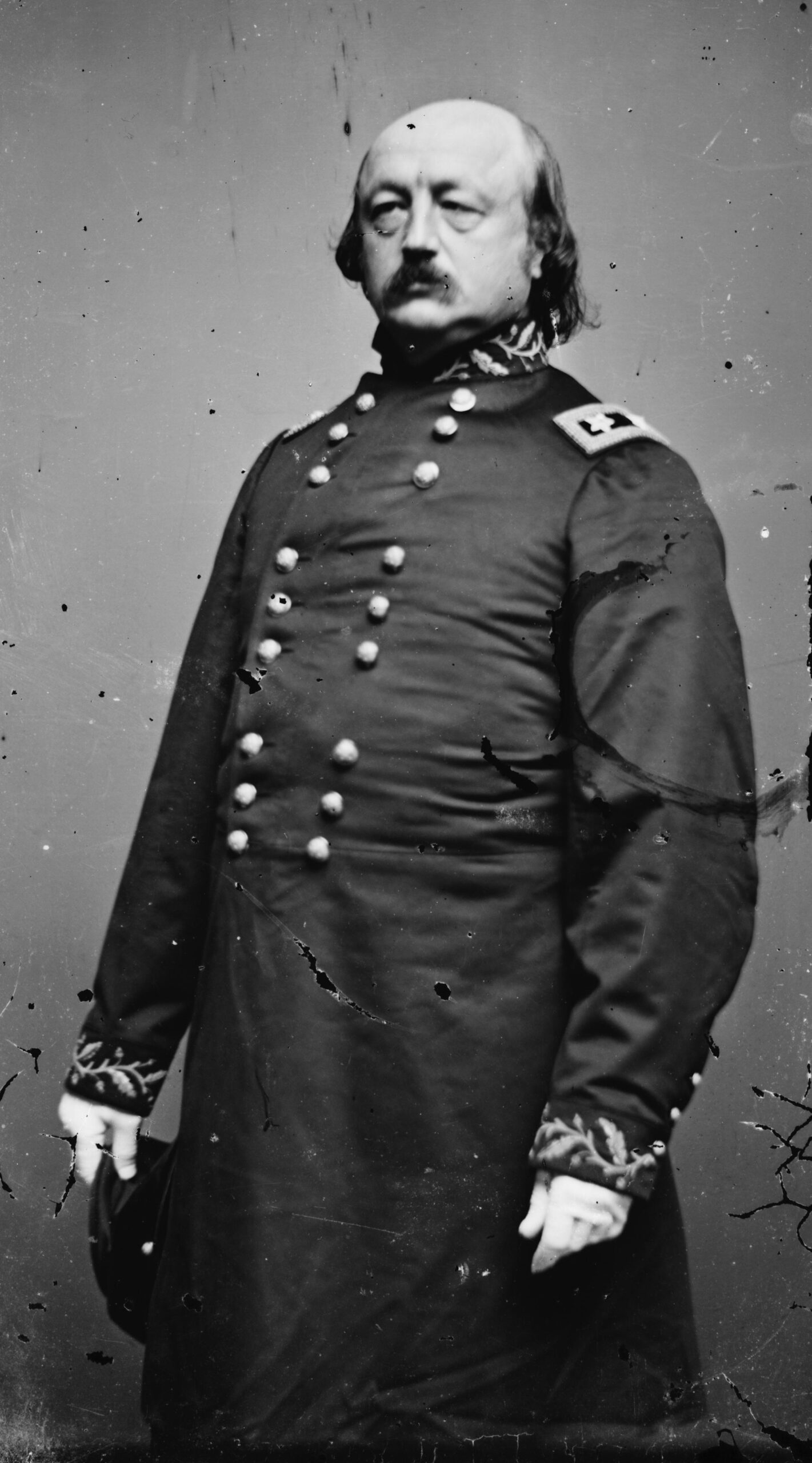

Although Virginia seceded from the Union on 4 April 1861, Fort Monroe remained under Union military control. In May, Major General Benjamin Butler, commander at Fort Monroe, permitted entrance to three slaves attempting to escape compulsory labor in the Confederate forces. When Butler was asked if he would return these slaves per the Fugitive Slave Act, he refused. He stated that these three men were “contraband of war”.

…and so a major change began.

What is contraband, you ask? Here, it is defined as property attained or confiscated by a foreign (in this case, warring) entity.

Since slaves were considered “property” and the southern states had formally seceded, General Butler could legally use this term to refuse their return. Even so, President Lincoln did not necessarily like this decision, because he did not want to consider the Southern States foreign. Nevertheless, in August, Congress passed the Confiscation Act of 1861, allowing the seizure of Confederate military property – slaves included. In September, the Union Navy began paying these “contraband” (oh, the concept!), and the Union Army soon followed suit. Finally, in March 1862, Congress passed the Act Prohibiting the Return of Slaves.

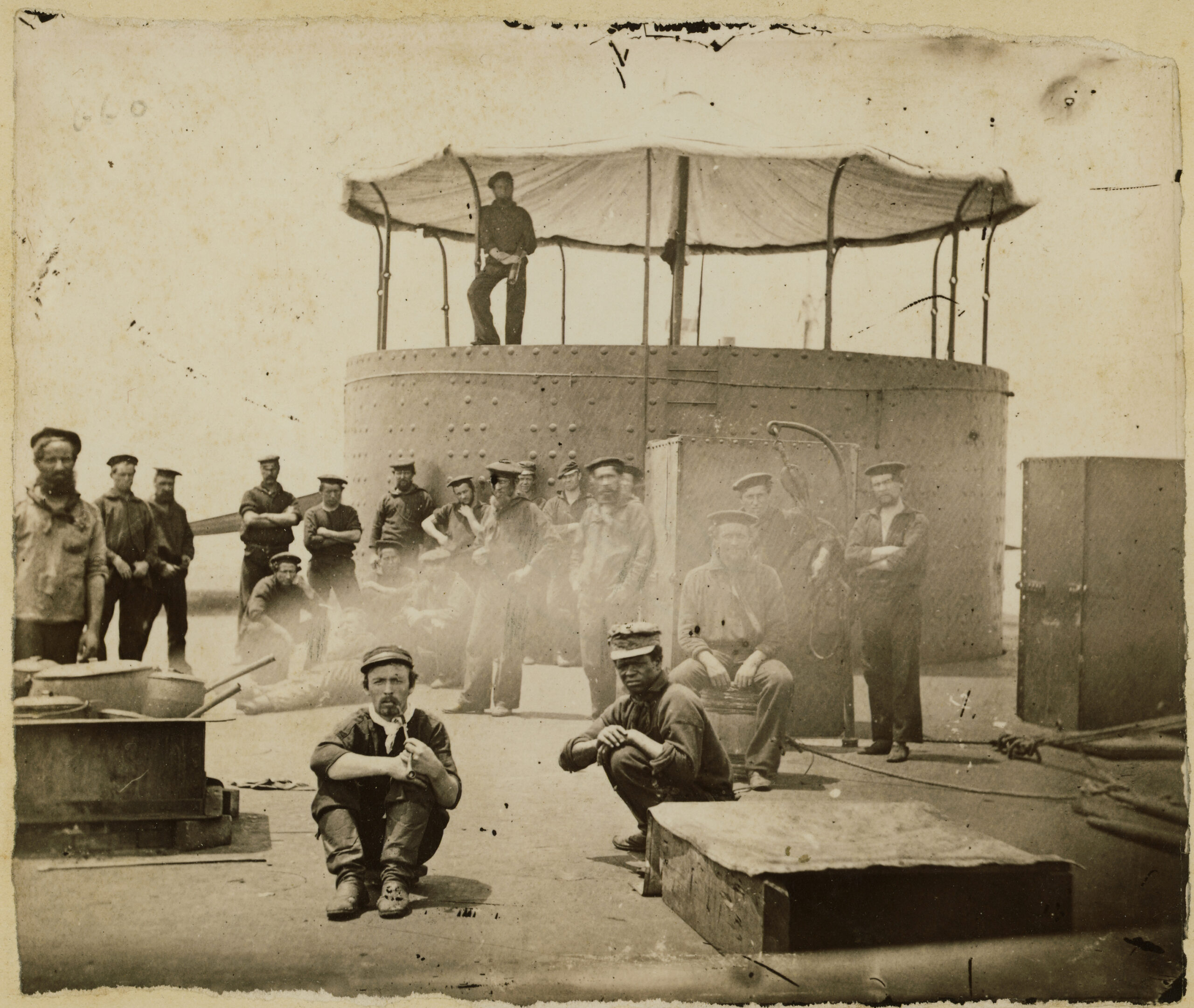

Additionally, there was nothing stopping freed African Americans from joining the Union forces (although the Emancipation Proclamation was not signed until 1 January 1863). While African Americans formed distinct units in the U.S. Army, the Navy integrated them into their ships’ crews. This has made current estimation of the number, or percentage, of African Americans in the Union Navy hard to attain. Union Navy enlistment papers stated an eye color, hair color, and skin complexion, but did not necessarily note ethnicity.

We can, however, positively identify eight men of African American descent in USS Monitor’s crew. We know there were more than these eight, because of correspondence and letters, like those of Assistant Paymaster William Keeler. In a note home to his wife, Keeler clearly stated that his first “servant” was African American, but not what his name was. Including this unidentified man, that means that there were at least two African American “plank owners” on Monitor.

Wait…what? What is a plank owner? A “plank owner” is a sailor who is part of the crew at the ship’s commissioning.

The second known plank owner of African American descent was William Nichols, a 19-year-old, freeman born in Brooklyn, New York. Nichols enlisted in the US Navy in February 1862. He was described on his enlistment papers as a “dark mulatto” and joined the crew as a landsman, before he was promoted to officers’ steward.

We also know of at least one confirmed “contraband” that joined Monitor’s crew. Siah Hulett Carter escaped from Shirley Plantation on 18 May 1862. The “poor trembling contraband” (Keeler, 19 May letter) rowed a boat from the plantation’s river bank out to the anchored USS Monitor by cover of night. Thinking the approaching boat could be a Confederate boarding party, Monitor crewmembers grabbed their small arms and lined the deck. One of them even shot a warning at the approaching vessel.

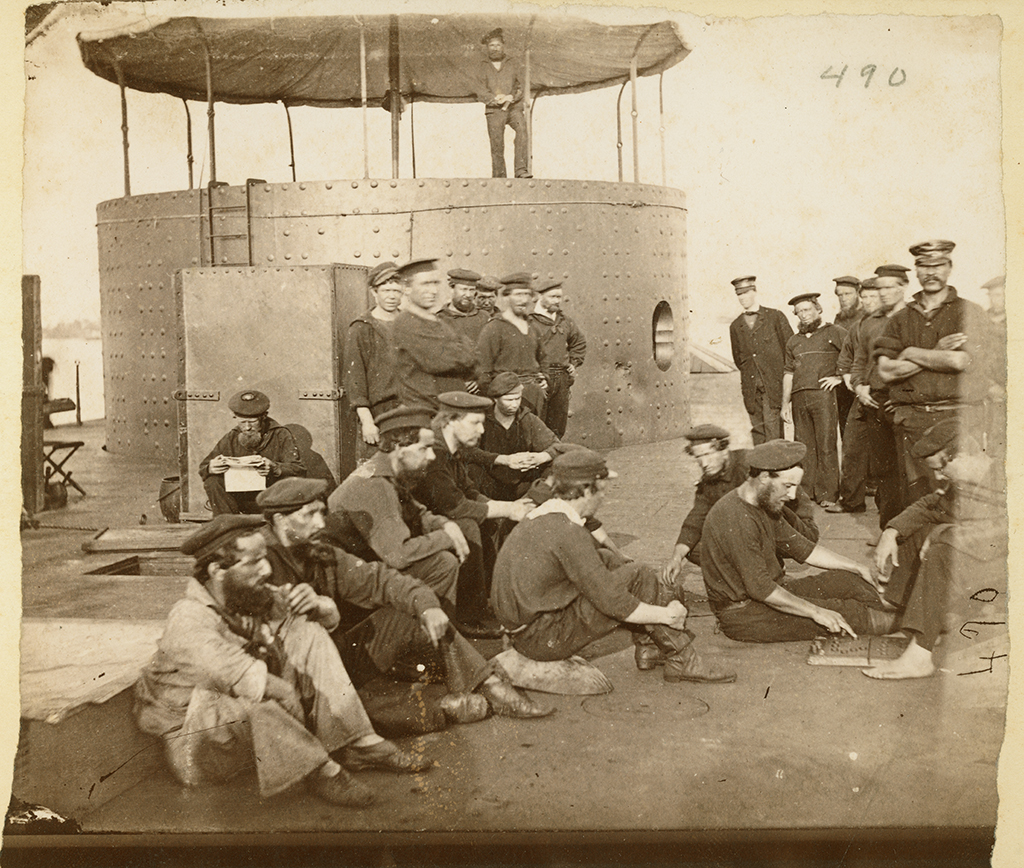

Carter cried, “‘O’ Lor’ Messa, oh don’t shoot, I’se a black man Massa, I’se a black man’” (Keeler, 19 May letter). Carter told the crew that “his master was a colonel in the rebel army…& told [all his slaves] that if any of them went on board of the yankee ships, the yankees would carry them out to sea, tie a piece of iron about their necks & throw them overboard” (Keeler, 19 May letter). Carter joined the crew as a first-class boy and assisted the cook. (Side note: Carter is the only African American crewmember we are lucky enough to have a picture of. See below.)

While the above statement was fiction, the Monitor – which was full with a crew of 65 – could not accept every contraband who escaped slavery and came to their ship. Engineer George Geer wrote to his wife on 9 June 1862:

The conunterbands [sic] still come to us. While I am writing you we have two men and two women, all of them young, not over twenty two or three, in the Engine Room, drying their cloaths [sic] as it rains very hard. They came from a plantation some five miles up the river. As soon as it stops raining they will be put in their old boat and be sent away with the Captain’s advise [sic] to go home again…

(I certainly hope these four made it to safety when they left Monitor.)

In total, there were four other probable contraband in Monitor’s crew. These included: Robert Cook, who was born in Gloucester County, Virginia, and joined the Monitor’s crew in October 1862 as a 16-year-old first-class boy. Robert Howard who was born in Howard County, Virginia, in 1824, and joined the U.S. Navy as a landsman in November 1862. Daniel Moore was also a landsman who joined the crew in November 1862; he was born in Prince William, Virginia. And (last-but-not-least) William Scott, born in Petersburg, Virginia, who joined Monitor’s crew on the James River in August 1862 as a first-class boy.

Rounding out our list of known African American crewmembers are Edward Cann and William Jeffery. Cann’s origins (i.e. place of birth and slave or freeman) have not been identified, but he joined the crew in November 1862 as a first-class boy. Jeffery, described as having a “mulatto” complexion, was born a freeman in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1837. He joined the navy as a landsman for a 3-year term in October 1861, and served on Pembina and in Washington Navy Yard, before he was transferred to Monitor in October 1862.

What happened to these men? Unfortunately, Robert Cook, Robert Howard, and Daniel Moore perished when Monitor sank on 31 December 1862. The other five all (thankfully) survived the ship’s sinking. William Nichols and William Scott deserted the Navy at different times in 1863. Edward Cann simply disappeared from subsequent records. And William Jeffery moved home to Philadelphia after the war.

By far, of the eight, we know the most about Siah Hulett Carter’s life after the sinking of Monitor. He continued to fight for the Union onboard USS Brandywine, Florida, Belmont, Wabash, and Commodore Barney. While serving on the last of these, he suffered from frostbite. After the war, he married Eliza Tarrow and they had 13 (yes, thirteen) children. He worked as a laborer in Philadelphia until his death in 1892 at the age of 53.

These men were essential members of Monitor’s crew and they were at the forefront of the important and impactful disappearance of an unjust social order.

To all the men and women who have served, and who continue to serve, we thank you.