On my team, Collections Management, we tend to move objects around fairly regularly and always with great care. Most of the collection is fairly small and manageable, or maybe requires an extra set of hands like with our ship models. Some of the heavier objects we keep on dollies or pallets so we can move them more easily. But, we have a sizable portion of the collection that requires heavy machinery like a forklift, which in turn requires teamwork from staff members who are qualified to use it. I can move heavy objects but there is a limit when it comes to anchors, boats, and cannons!

The week before the museum temporarily closed due to COVID-19 (coronavirus), we needed to move several large objects so we could rearrange some of our shelving. I was amazed at how many staff members offered to help! We had people from conservation, exhibit design, buildings and grounds, facilities, and three of our volunteers who all came together. Through their amazing team spirit, we moved everything safely and now have better access to some of the objects to get a better view of them and catalog them more thoroughly. The objects we moved included two diving air compressors, ship’s bells, engineering gauges, a range finder, and a large ship’s wheel.

Cataloging is a museum way of saying that we are going to really research something in depth, to have as much history and information about an object for researchers and interpretation for programming or exhibits. I love when I can really catalog something because I learn so much, not only historical facts but it’s a way to really get to know the collection and what we have to offer. It also gives you a sense of personal connection to the artifacts!

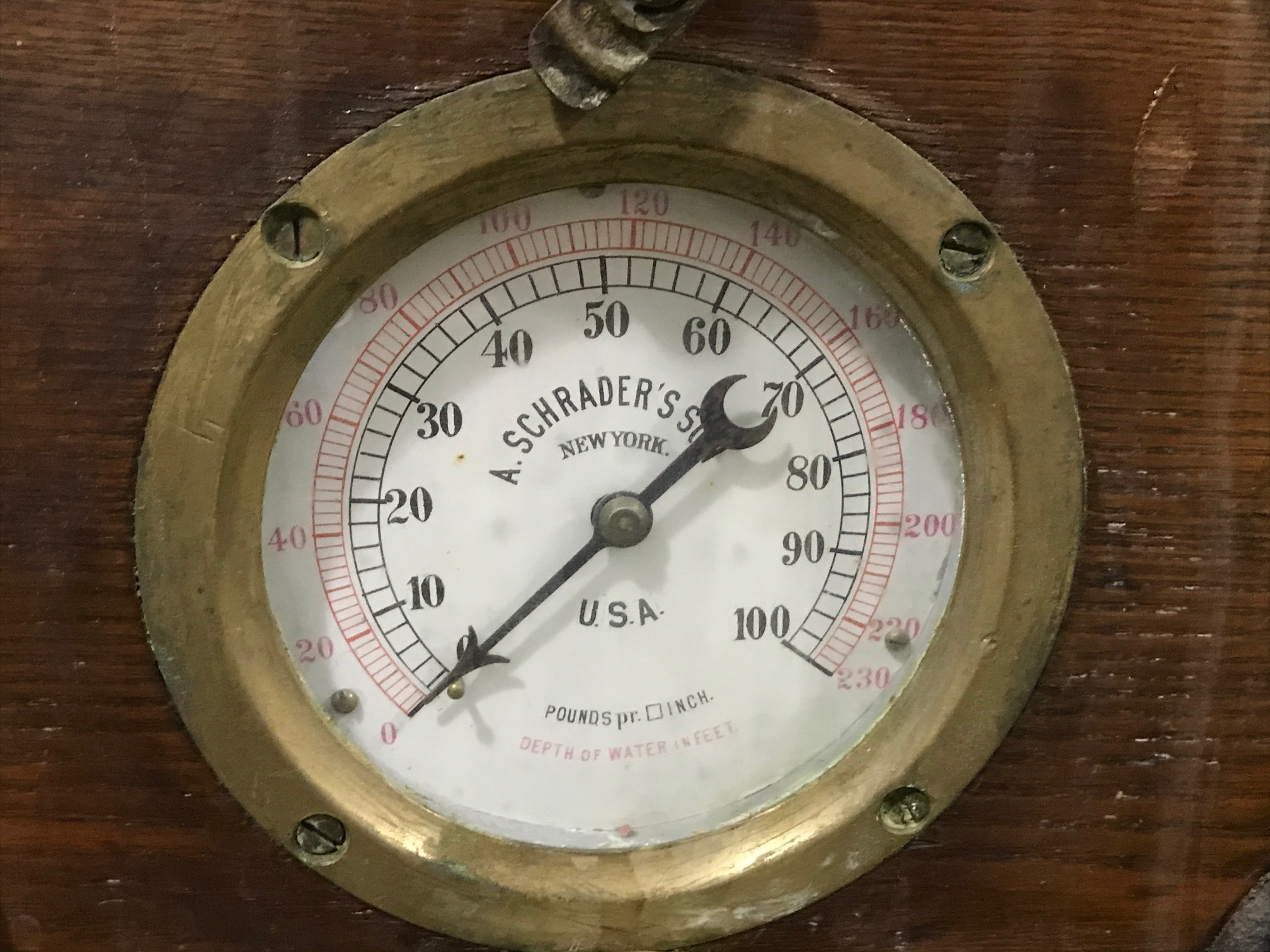

First, my two awesome interns helped gather all of the marks off of the objects we moved from the boiler row, starting with the diving air compressors. Air compressors are the machinery that forces air from the surface through hoses to the submerged divers so they can breathe and do their work. We used flashlights and cameras to gather every inscription, label, and identifying numbers or words we could find. This was tricky as the machinery had many gauges and various parts inside of the wooden cabinet, which meant a lot of careful twisting and searching to read the information.

The interior of the 1942 air compressor. There are numerous parts from different companies, each with their own hard-to-access marks.

Finding the marks can be like a treasure hunt to not only find them but to read what they say after years of wear, so it was great having their help to have extra eyes to verify that we had the correct spelling of each mark. We now have the company names of who made or used the various parts, as well as specific part numbers. I started my research with the companies on the compressors because both of them had the same names and I could catalog two objects at the same time, efficiency for the win!

They were made by A. Schrader’s Son, a company founded in 1844 by August Schrader. He and Christian Baecher were turners and brass finishers according to the federal census records. The business changed when Schrader watched an underwater race one day in the New York harbor and realized that he could make the diving equipment better. This began a lifelong interest in diving equipment and he sold his first two dive helmets for $12 each in 1849 to the Union India Rubber Company. In January 1850 he sold his first air pump to the same company for $25. Baecher seems to have left the company in the early 1850s, and Schrader exhibited more advanced air pumps at the Industrial Fair of 1853 at the Crystal Palace in New York. What I found most fascinating is that August Schrader’s son, George Schrader, joined the company and then patented the pneumatic tire valve, known today as the Schrader valve and still used on almost every car and bicycle tire!

According to his obituary, George allowed the board to run the company and he moved to Iceland to care for the Iceland ponies. If you had spare time and the financial ability, wouldn’t you do that, too? After several years, he became ill and wanted to travel back to New York, but being of German heritage in 1915 he chose not to travel through England so that he wouldn’t be arrested with WWI raging. He died under somewhat curious circumstances on a trawler going to Norway.

Another company name found on the air compressors was the Merritt-Chapman & Scott Corporation, a salvage and wrecking company that probably used one of these compressors rather than manufacturing parts for them. They began in 1860 and were eventually hired to do the initial investigation into the explosion of USS Maine in the Havana Harbor, an incident that kicked off the Spanish-American War. Recent investigations have determined that the explosion came from inside the ship rather than a Spanish bomb from outside the ship.

Another company name found on the air compressors was the Merritt-Chapman & Scott Corporation, a salvage and wrecking company that probably used one of these compressors rather than manufacturing parts for them. They began in 1860 and were eventually hired to do the initial investigation into the explosion of USS Maine in the Havana Harbor, an incident that kicked off the Spanish-American War. Recent investigations have determined that the explosion came from inside the ship rather than a Spanish bomb from outside the ship.

After the air compressors, I switched my attention to an engine plate with steam gauge and counter. As far as machinery goes this is a very pretty piece with several names on it, including Quintard Iron Works and N.F. Palmer Jr. & Co. These companies were much more difficult to find, and I pieced my history together with census records, newspaper articles, and city directories. George W. Quintard started his company around 1869, manufacturing steam engines and other machinery. His son-in-law, Nicholas F. Palmer, Jr., started his own company and eventually ran Quintard Iron Works as a kind of subsidiary of his own. I was surprised to discover that this company made the machinery for USS Maine and was investigated by Merritt-Chapman & Scott who used our air compressor!

After the air compressors, I switched my attention to an engine plate with steam gauge and counter. As far as machinery goes this is a very pretty piece with several names on it, including Quintard Iron Works and N.F. Palmer Jr. & Co. These companies were much more difficult to find, and I pieced my history together with census records, newspaper articles, and city directories. George W. Quintard started his company around 1869, manufacturing steam engines and other machinery. His son-in-law, Nicholas F. Palmer, Jr., started his own company and eventually ran Quintard Iron Works as a kind of subsidiary of his own. I was surprised to discover that this company made the machinery for USS Maine and was investigated by Merritt-Chapman & Scott who used our air compressor!

Quintard’s grandson (also named George W. Quintard) received $1 million after his grandfather passed away in 1913, but according to the newspapers no one ever taught the boy how to handle money. By 1914, two women sued him for breach of promise, stating that he had proposed marriage to each of them and then essentially left them at the altar because he was already married. In 1915, a jewelry store sued him for non-payment, and his response was that an employee abused his situation, that “his memory is foggy, as he was drunk all last January and February.” Two straight months, yikes! Sadly, he fell down a set of stairs and died in 1919 from a fractured skull.

The history of our objects themselves is fascinating, but I love stumbling onto the connections they have to other’s histories! I never would have thought when I started my research that a diving air compressor and a ship’s engine gauge would have any connection to the Spanish-American War, but now they have an extra story to tell beyond their own. Our collection holds a world of surprises!

Below are other marks that we found on the air compressors: