CSS Albemarle was one of three ironclads laid down in early 1863 to combat control of the North Carolina sounds. Only the ram Albemarle would become operational and able to contest Union control of eastern North Carolina until its dramatic sinking in October 1864.

Cornfield Ironclad

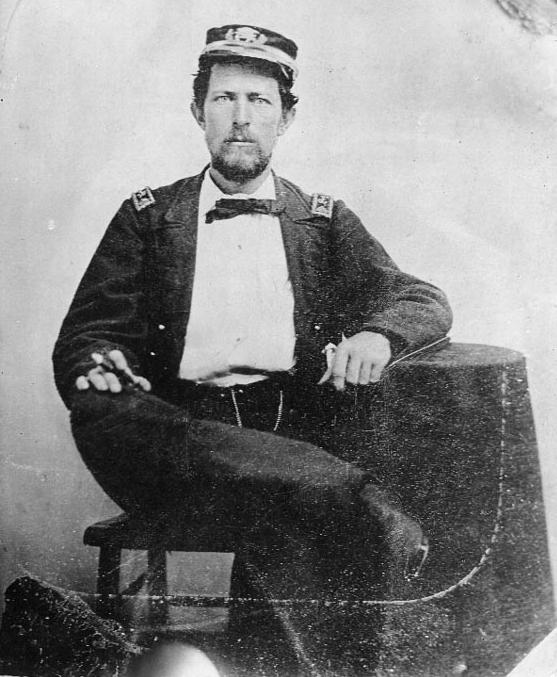

A 19-year-old boatbuilder, Gilbert Elliot of Elizabeth City, North Carolina, sent a proposal to Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Russell Mallory. His idea: to construct ironclads up the various rivers that were out of reach of Union forces. Mallory agreed. So, Elliot submitted sketches to Confederate Naval Constructor John L. Porter, who established working drawings.

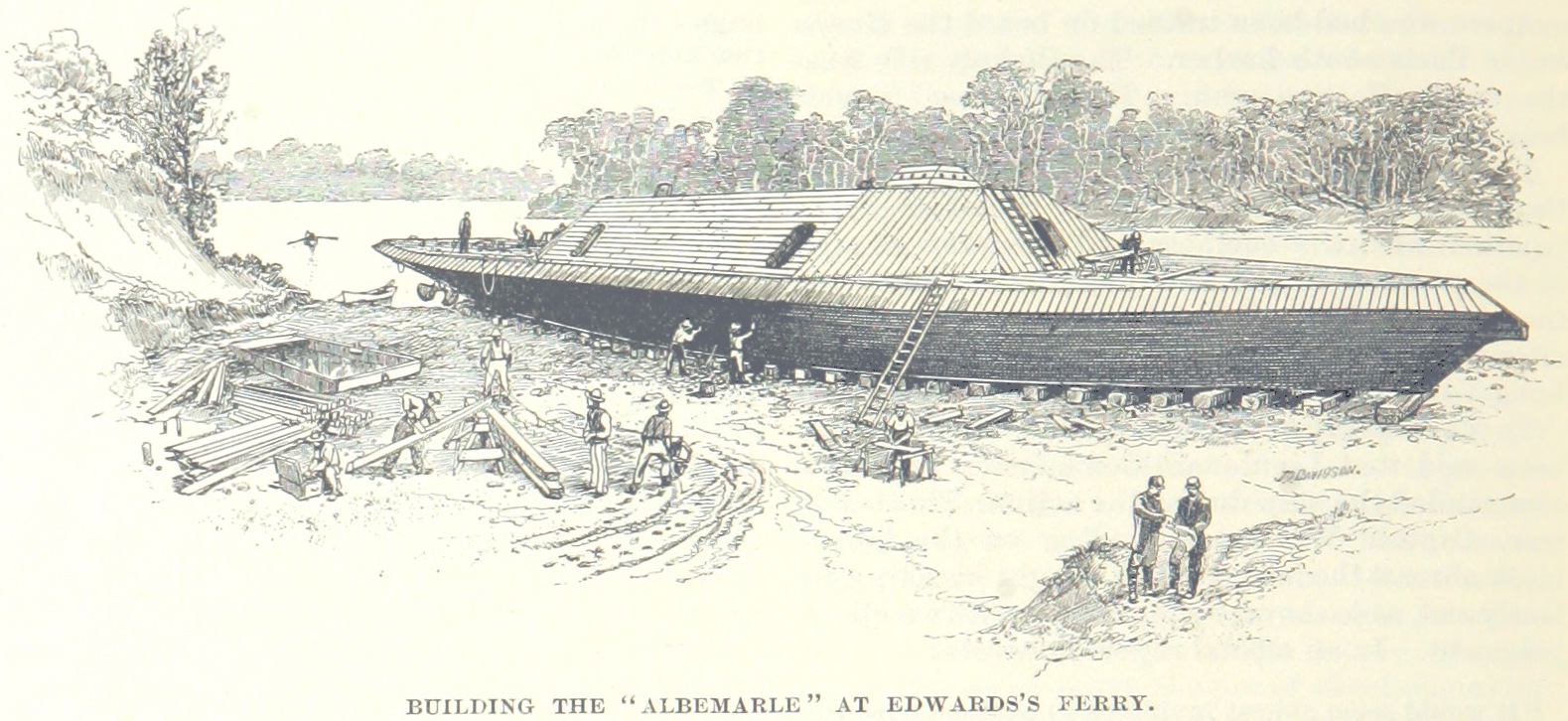

Elliot and his partner, William P. Martin, then received a contract to construct two ironclads: one on the Roanoke River, and the other on the Tar River (soon to be burned by the Federals). Elliot selected a site at Edwards’s Ferry, North Carolina, to build the warship in a makeshift shipyard in Peter Smith’s cornfield. Several forges were located on Smith’s plantation. He would soon receive a drill press. His brother owned a nearby sawmill.

Peter Smith became superintendent of construction. Lieutenant James W. Cooke, CSN, supervised the construction. Cooke became known as the ‘ironmonger captain’ as he sought to receive iron rails from various North Carolina railroads. He collected more than 707 tons that was sent to Richmond’s Tredegar Foundry before being sent back to Halifax, North Carolina, as iron plates. Once the wooden shield and hull were completed, the vessel was launched at Edwards’s Ferry. The hull was damaged, and Albemarle was towed to Halifax, to receive its engines, guns, and iron plating.

Form Follows Function

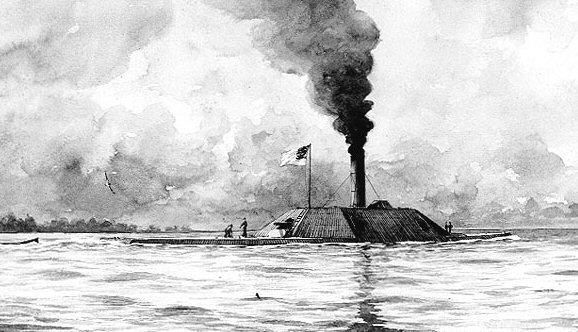

Albemarle’s casemate design had a totally different look than other ironclads. Porter designed it to be built with 30 degree sloped sides and an octagonal look. Often called the diamond pattern, the casemate was smaller which enhanced stability and enabled a lesser draft. The ironclad was flat bottomed, giving it a 9-foot draft, perfect for the shallow waters of the Carolina sounds. Albemarle had a beam of 35.4 feet and a length of 158 feet. Its shorter length allowed the vessel to work down the Roanoke River to the Albemarle Sound. Propulsion was achieved by two horizontal non-condensing engines with two boilers. Elliot built the engines which featured two 3-bladed screws. The ironclad could make four knots.

The casemate was covered by four inches of iron plate with pine backing. It had just enough space to contain two 6.4-inch double-banded Brooke rifles. Each rifle weighed more than six tons. There were six gun ports with iron shutters. The Brooke guns were mounted on the ironclad’s centerline, enabling the guns to fire forward or to have a two-gun broadside on either port or starboard. Each pivot gun had an arc of 180 degrees. The hull had a built in ram that was four feet long, covered by four inches of iron plate.

Grand Strategy

The Confederacy was anxious to finish Albemarle. In February 1864, Lieutenant Robert Minor went to North Carolina from Richmond to inspect the ironclads CSS Neuse in Kinston and CSS Albemarle in Halifax. He reported that Albemarle had all its engines installed and the last course of iron plate was being installed. General Robert E. Lee wanted Confederate troops to strike at New Bern and Plymouth; however, this could only be successful if either or both ironclads could support these infantry assaults.

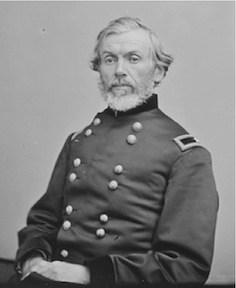

General George Picket had left his New Bern position to return to Virginia as the campaign season was about to begin. He left General Robert Hoke to attack Plymouth. The town was defended by several Union gunboats and General Henry Wessels’s small garrison.

Hoke met with Commander James Cooke. The naval officer assured him that Albemarle would be there when the Confederates began their infantry assault.

The ironclad Albemarle was commissioned on April 17 and began steaming down the Roanoke. Mechanics onboard were still completing work on the vessel. Hoke began his attack the same day.

Albemarle Strikes Southfield

On April 18 Albemarle had to stop for repairs, but the ironclad anchored above the obstructions placed just above Plymouth. After they were surveyed, it was determined that there was sufficient water covering them for the ironclad to proceed. Early the next morning, Albemarle steamed toward Plymouth and passed Fort Grey on Warren’s Neck. The fort sent shells against the ram with no ill effects; and Albemarle soon came abreast of Plymouth.

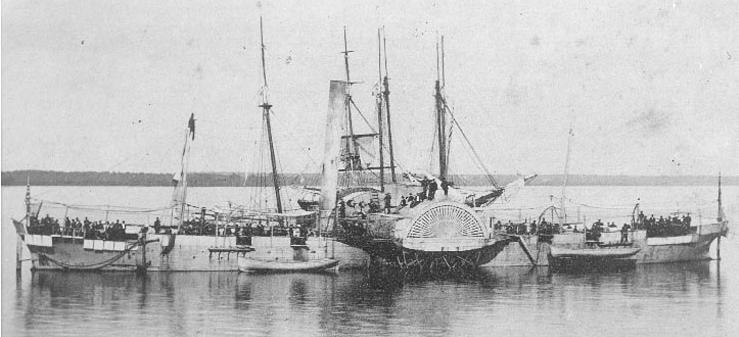

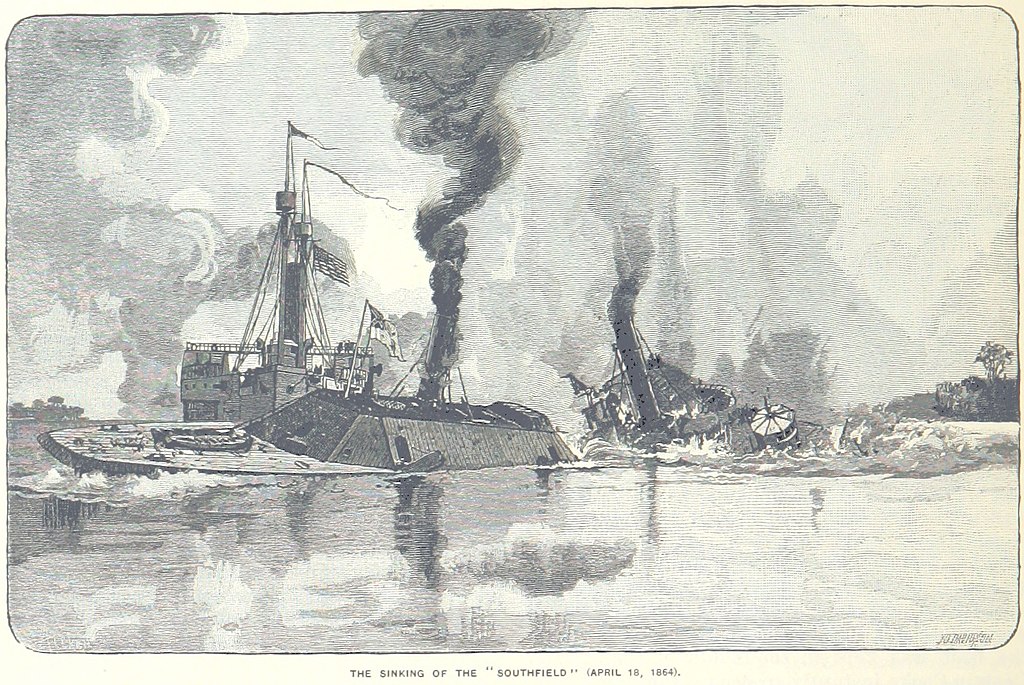

Cooke sighted two Union gunboats near the mouth of the river. Lieutenant Commander Charles Flusser had two of his most powerful gunboats, USS Miami and USS Southfield, prepared to meet the Confederate ironclad.

Flusser had lashed the warships together with hawsers, the idea being to force Albemarle between his vessels and pound the Confederate ram into submission with their heavy guns.

As Albemarle approached the Union gunboats, Cooke noticed the rope linking Miami with Southfield. So, he steered his ironclad toward the Roanoke’s south shore, then swerved his vessel against the Union gunboats.

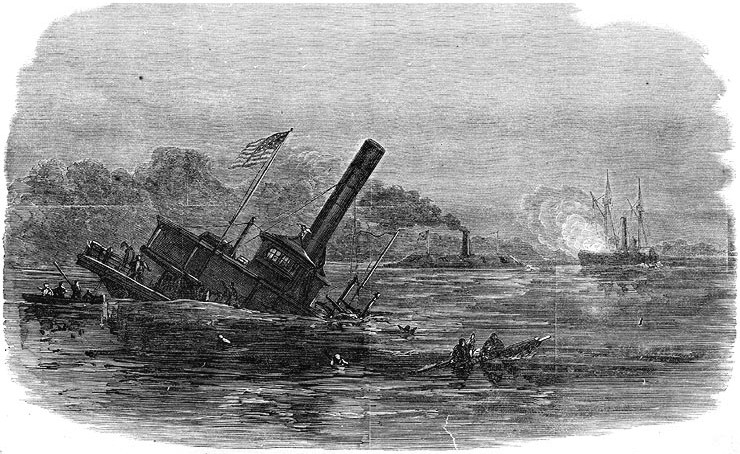

At full throttle, Albemarle glanced off Miami’s port bow and plunged its raminto Southfield which began sinking immediately. Even though Cooke had ordered engines just before impact, Albemarle was wedged 10 feet into Southfield and could not free itself as the Union vessel quickly sank. Consequently, the ram’s bow was pulled under as water poured into the forward gun ports. Somehow, Albemarle broke free.

While lodged in the sinking Southfield, Albemarle was struck by several shells from USS Miami. One of those shells bounced off the sloped iron sides, rebounding onto Miami’s deck, landing at Flusser’s feet. He was killed instantly. Miami and the other Union gunboats quickly escaped. Albemarle began shelling the Union defenses and General Henry Wessels surrendered.

Victory

Albemarle had succeeded in forcing the Federals to abandon Plymouth, Edenton, and Little Washington. Victory was sweet; however, the Union was now plotting for revenge.

Excerpted from A History of Ironclads: The Power of Iron Over Wood, John V. Quarstein. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2006. Available in the Museum Web Shop: https://shop.marinersmuseum.org/a-history-of-ironclads.html