Confederate Retreat from the Peninsula

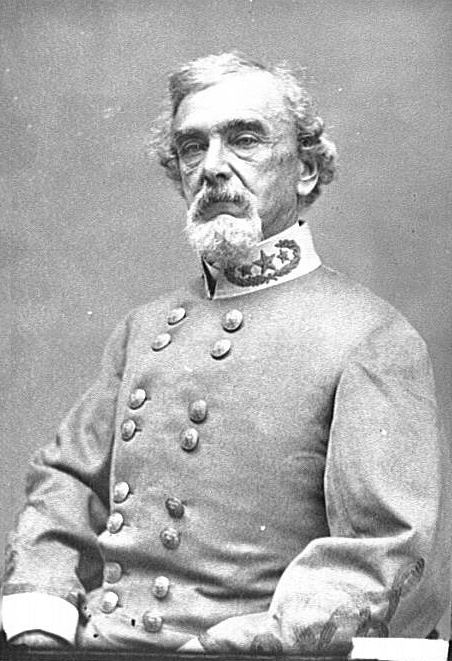

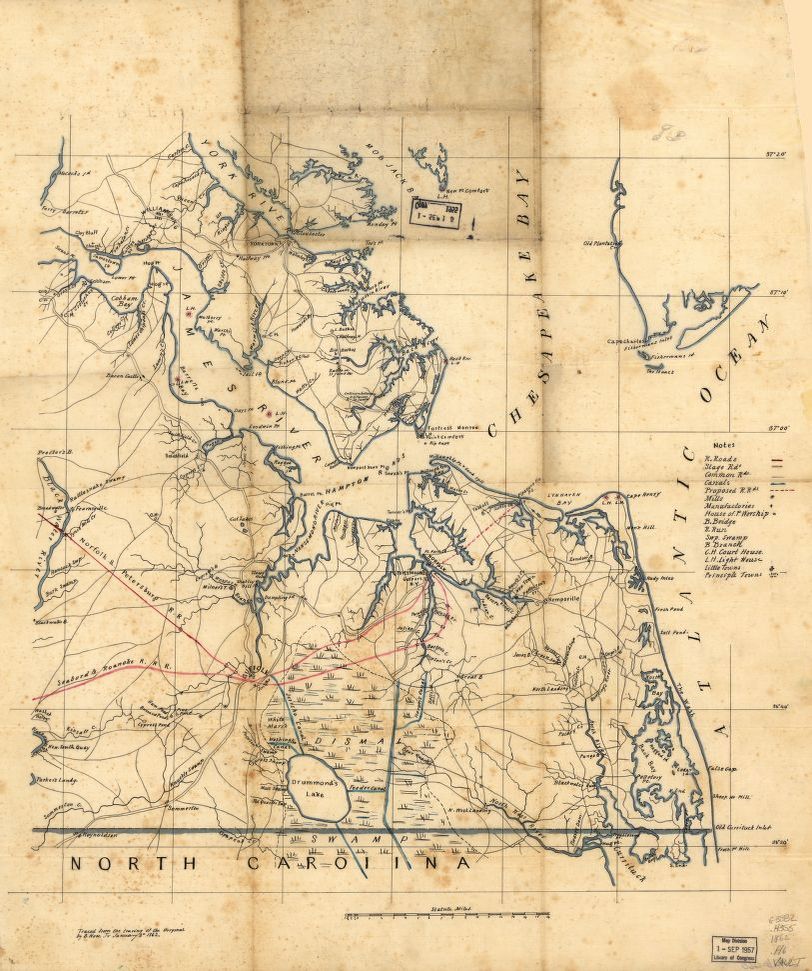

Time was running out for the Confederate navy in Hampton Roads. On the evening of May 3, 1862, General Joseph Eggleston Johnston ordered the evacuation of the Confederate Warwick-Yorktown Line. Johnston believed that the “fight for Yorktown must be one of artillery, in which we cannot win. The result is certain, time only doubtful.”

Johnston’s retreat up the Peninsula toward Richmond forced the Southerners to make plans to abandon the port city and navy yard. When he learned of Johnston’s withdrawal, Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Russell Mallory telegraphed Flag Officer Josiah Tattnall that Virginia alone would have to prevent the enemy from ascending the James River.

Confederate Preparations to Abandon the Yard

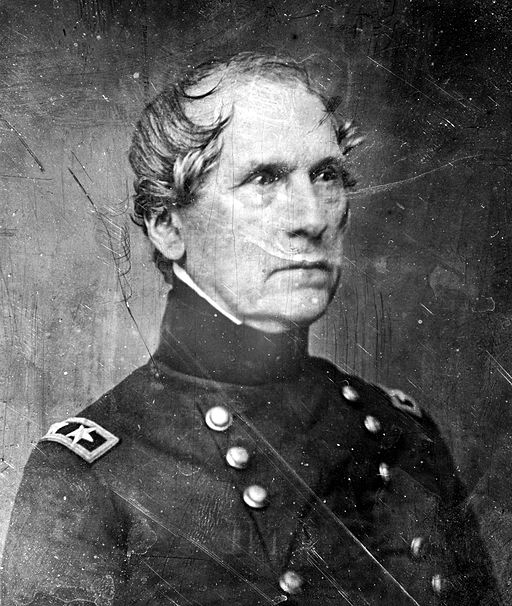

Flag Officer S. Smith Lee, the new commandant of the Gosport Navy Yard, began the evacuation of the yard on May 1, 1862. All the yard’s salvageable material was dismantled and moved to Richmond, Virginia, and Charlotte, North Carolina. It was a herculean and desperate effort.

On the evening of May 6, CSS Yorktown, towing the incomplete CSS Richmond and CSS Hampton, and CSS Jamestown, carrying ordnance supplies and heavy guns, made their escape from Norfolk under the cover of darkness.

Lincoln Comes to Hampton Roads

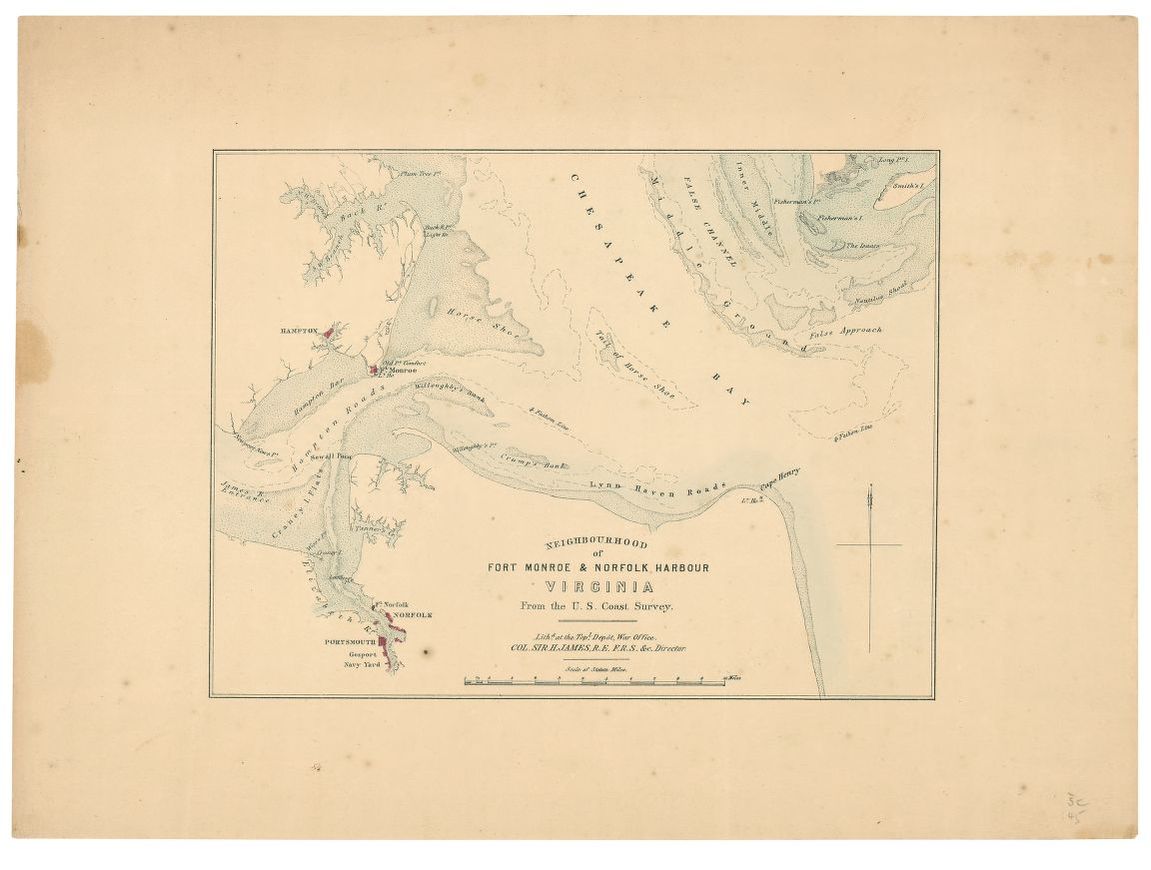

President Lincoln was disenchanted with the Army of the Potomac’s slow progress up the Peninsula, as well as with the US Navy’s inability to contend with CSS Virginia. So, Lincoln traveled to Fort Monroe to prompt resolute action. He arrived at Old Point Comfort on the evening of May 6, accompanied by General Egbert L. Viele, Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase, and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

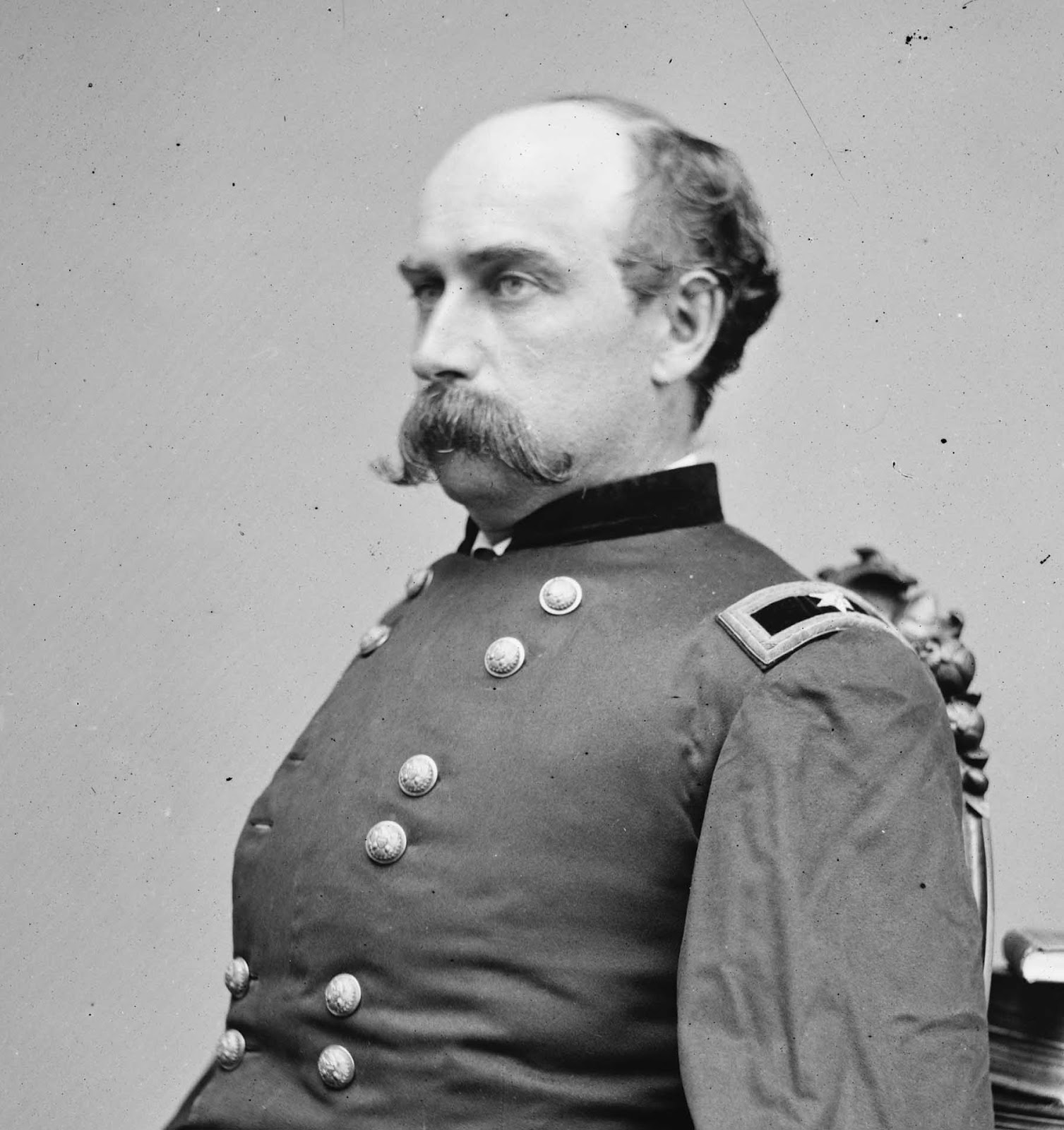

Since General McClellan was advancing toward Richmond after the May 5 Battle of Williamsburg, Lincoln’s focus was on Norfolk and the Merrimack. A council of war was held with General John E. Wool, commander of the Union Department of Virginia, and Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough, commander of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Lincoln was still disturbed by the lack of naval action. He ordered Goldsborough to put his fleet in simultaneous motion against Norfolk and the James River.

Goldsborough, still suffering from the dreaded ‘Ram Fever’ disease, told the president that the US Navy did not have the resources to complete both tasks. Nevertheless, Lincoln pressed Goldsborough to plan a two-prong attack for May 8.

Showdown in Hampton Roads

USS Monitor, supported by the ironclad Naugatuck and the wooden warships USS Susequehanna, San Jacinto, Dacotah, and Seminole attacked the Confederate batteries on Sewell’s Point. Meanwhile, Commander John Rodgers took the ironclad USS Galena and the wooden gunboats USS Port Royal and USS Aroostock into the James River. Rodgers’s command then attacked and defeated two Confederate earthen forts, Boykin and Huger.

Monitor and its consorts moved past Fort Wool and began shelling Sewell’s Point until CSS Virginia entered Hampton Roads.Tattnall faced a difficult decision. He could either take his ironclad up the James River to stop the Union from moving up the river. Or, he could block the advance of Monitor. Since Rodgers was by now far enough up the James River where the Confederate ironclad could not reach due to its draft, Tattnall decided to defend his base and attack Monitor.

While it appeared that a second contest between the two ironclads might occur, Goldsborough ordered the squadron to return to its anchorage near Fort Monroe.Tattnall, disgusted by the Federal retreat, ordered his crew to “fire a gun to windward” as Virginia returned to its buoy.

Lincoln Takes Command

Abraham Lincoln watched the entire action from Fort Wool. Rodgers had now isolated Norfolk by his movement up the James River. However, the president now realized the Confederate port city could only be taken by an amphibious operation. Lincoln surveyed the beach at Ocean View. He then advised General Wool that it was the perfect place for the landing.

Under the cover of a naval bombardment, General Wool ferried 6,000 soldiers in ferry boats to Ocean View, supported by three artillery batteries commanded by General Max Weber. A second wave of troops followed under the command of General Joseph Mansfield. Wool’s command landed unopposed on the morning of May 10, and marched toward Norfolk.

Mayor Lamb and the Keys To Norfolk

The Federals reached the outskirts of Norfolk. There, Wool was met by Mayor William Lamb and a select committee of Norfolk’s municipal council. Lamb welcomed the Union army with a ceremony designed, according to General Viele, as “a most skillful ruse for the Confederates to secure their retreat from the city.”

The ceremony lasted until dark, and according to General Viele, “the Confederates were hurrying their artillery and stores over the ferry to Portsmouth, cutting the water-pipes and flooding the public buildings, setting fire to the navy yard, and having their own way generally, while our General was listening in the most innocent and complacent manner to the long rigmarole so ingeniously prepared by the mayor.”

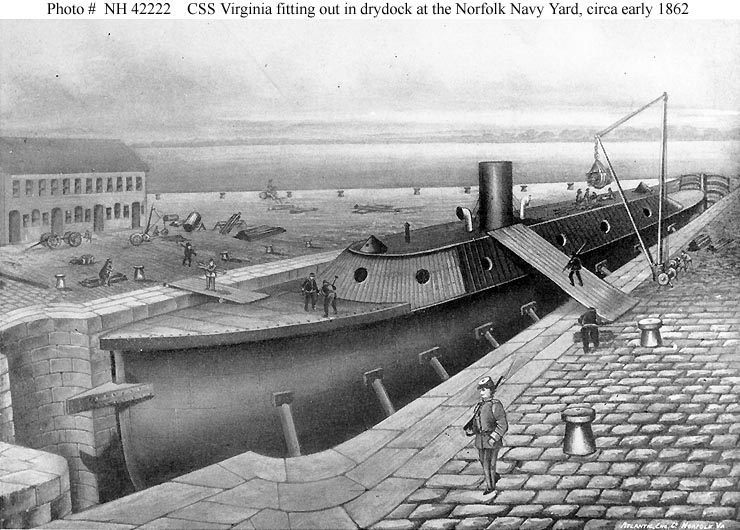

Lamb’s filibuster tactics enabled the partial destruction of Gosport Navy Yard. Once again, the dry dock was not effectively destroyed by the retreating forces, and other ship repair resources were untouched.

Bright Beginning…Sad Finish

General Benjamin Huger, commander of the Confederate Department of Norfolk, abandoned Norfolk and all the Elizabeth River batteries on the evening of May 9 to escape to Suffolk. Meanwhile, CSS Virginia was not informed of the Confederate retreat. This left the Confederate ironclad without a port.

Flag Officer Tattnall was left with few choices. He could take his ironclad out and attack the Union fleet, perhaps destroying several enemy vessels before sinking in a blaze of glory. Neither this course of action, nor any effort to take Virginia out to sea en route to another Southern port was advisable. The ironclad needed to go up the James River to Richmond; but, the vessel’s deep draft was a serious problem. Efforts to lighten the ironclad were to no avail. Virginia was scuttled off Craney Island during the early morning of May 11, 1862.

Lincoln Goes to Norfolk

Monitor led several Union vessels up the Elizabeth River past the smoldering wreck of Virginia to Norfolk. The last vessel in line was the steamer USS Baltimore with President Lincoln aboard. The president took off his hat and bowed as he passed Monitor.

Lincoln was pleased with the events that occurred while he was in Hampton Roads. His presence in Hampton Roads resulted in the surrender of Norfolk, the evacuation of the strong batteries defending the Elizabeth River, the recapture of the Gosport Navy Yard, and the destruction of “the rebel iron-clad steamer Merrimack..” Thanks to his drive and leadership, the Union seemed assured of capturing Richmond.

Excerpted from CSS Virginia: Sink Before Surrender, John V. Quarstein. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2012. and A History of Ironclads: The Power of Iron Over Wood, John V. Quarstein. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2006. Available in the Museum Web Shop: https://www.google.com/url?q=https://shop.marinersmuseum.org/sink-before-surrender-pb.html&sa=D&source=hangouts&ust=1587055613966000&usg=AFQjCNGlDlDHoLEWTXRLO71bPBmtARqV5A