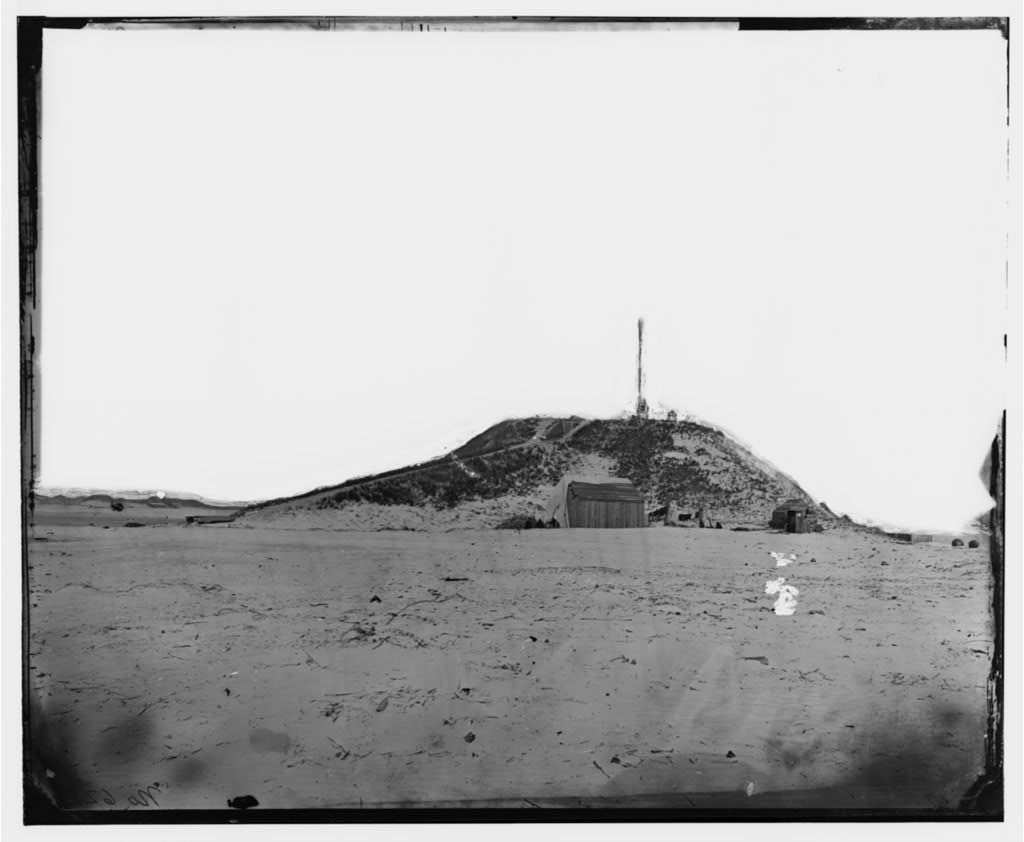

Fort Fisher, N.C., Interior view of first three traverses on land face, 1865. Timothy H. O’Sullivan, photographer. Courtesy Library of Congress.

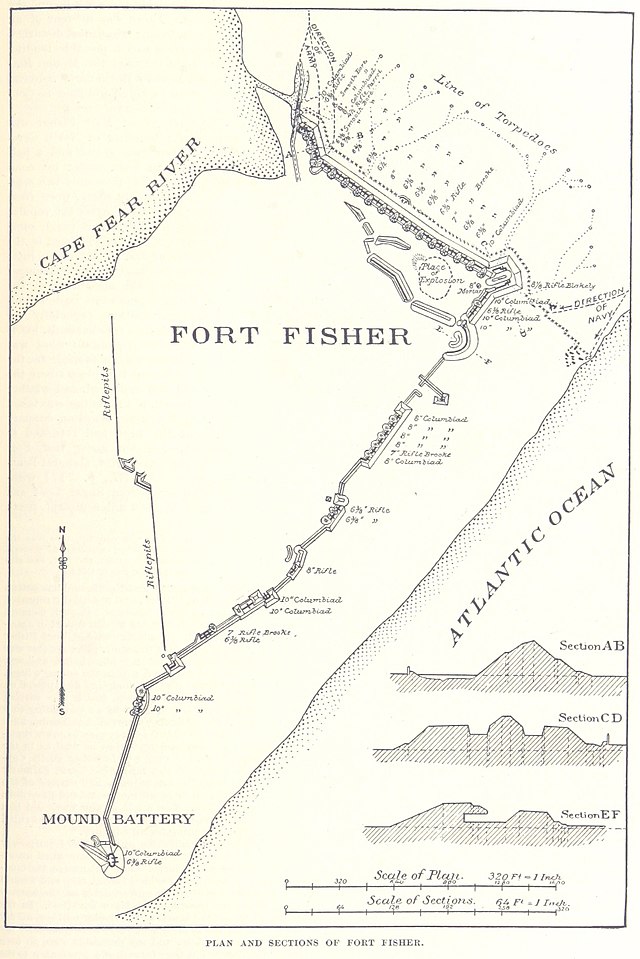

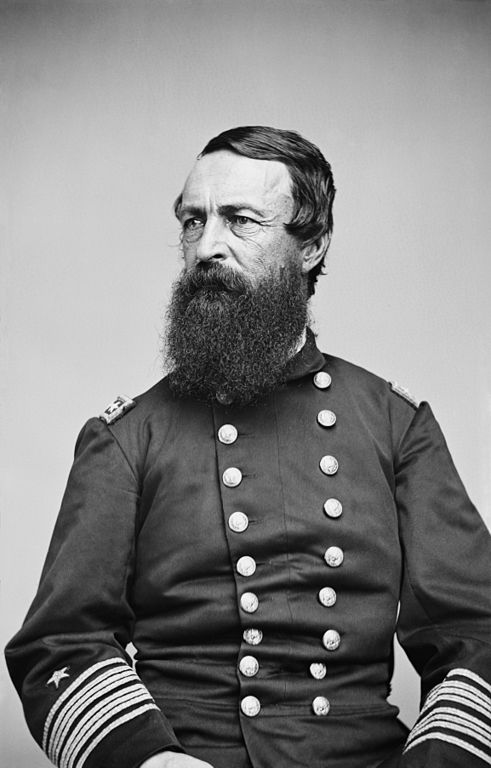

Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles had long recognized Wilmington, North Carolina, as the key blockade runners’ haven in the war. He had tried to create an expedition to capture Wilmington’s prime defender, Fort Fisher. Welles, in conjunction with Rear Admiral Samuel P. Lee, conceived an attack where monitors would pass through Cape Fear’s Old Inlet and bombard Fort Fisher from the rear. A great idea: however, this mode of assault was impractical as the new Passaic-class monitors had too drafts too deep to enter the river. The Federals; nevertheless, did not forget about Cape Fear.

CONCEPT CONCEIVED

The Federals knew that Wilmington needed to be closed; yet, they also recognized the magnitude and extent of the Cape Fear defenses. Fort Fisher was key to General Robert E. Lee’s defense of Petersburg and Richmond. The food, weapons, ammunition, clothing, and medicines that Lee’s army relied upon all came from Wilmington, North Carolina. If this port city were to be captured, Lee would have to abandon his trenches outside of Petersburg.

As 1864 neared its close, Fort Fisher became a major target. General U.S. Grant could spare the troops as the campaigning season in Virginia was over due to winter’s arrival. And since Mobile Bay had been captured, Wilmington was now the Confederacy’s outlet to the world. This doorway had to be closed so that the great Federal snake Anaconda could finish its work.

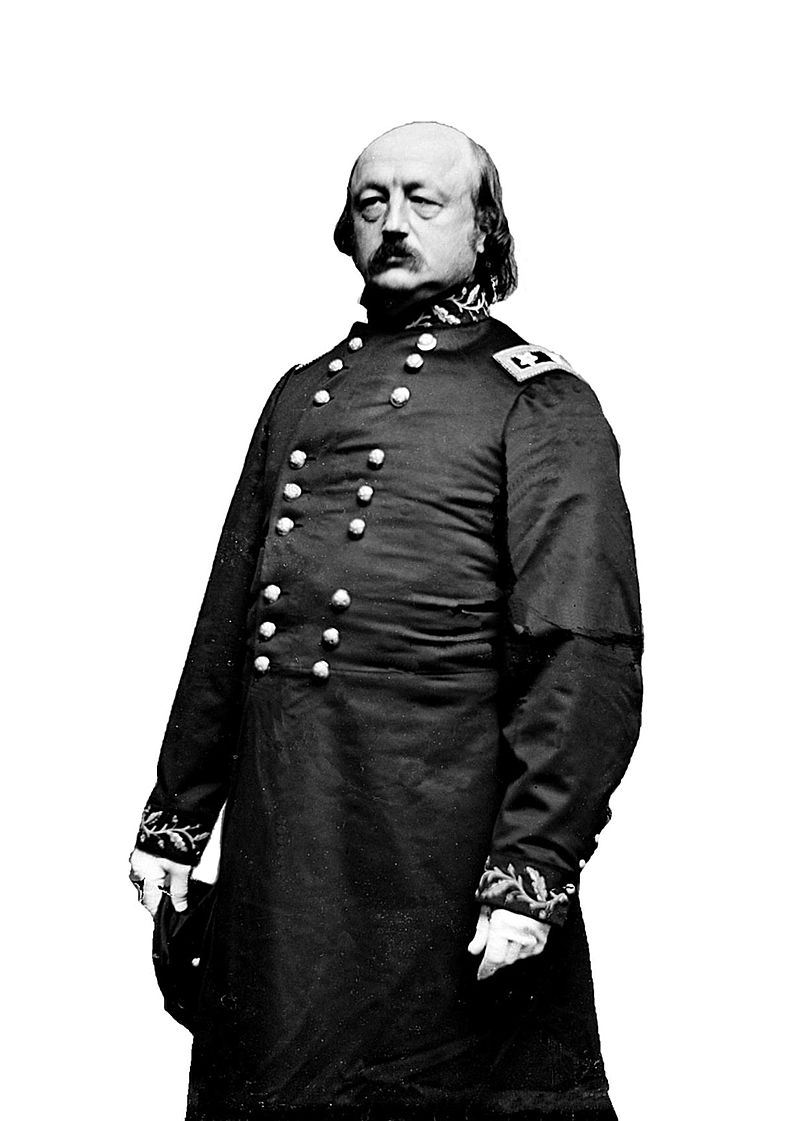

As General Ben Butler’s Army of the James was ‘bottled-up’ at Bermuda Hundred, Grant decided to send Major General Godfrey Weitzel’s division to join with Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter’s North Atlantic Blockading Squadron in efforts to capture Fort Fisher. When Butler learned of this decision, he insisted that he should personally command the expedition as he was the commander of the Union Department of Virginia and North Carolina. Despite his misgivings, Grant agreed to let Butler take charge.

THE BEAST

Benjamin Franklin Butler was an unscrupulous lawyer and slick politician from Lowell, Massachusetts. Originally a Democrat, he changed his party affiliation to Republican when the Civil War erupted. In 1861, Butler was a militia general who tricked his way into command of the 6th and 8th Massachusetts regiments to open the way through Maryland to Washington, D.C. The 6th Massachusetts’ march toward Washington resulted in the April 19, 1861 Baltimore Riot.

Butler was able to occupy Maryland’s capital, Annapolis, and eventually Baltimore. His efforts stopped the secessionist movement in Maryland. Promoted to major general of volunteers, he was assigned as commander of the Union Department of Virginia, headquartered at Fort Monroe. There he proclaimed three escaped slaves as ‘Contraband of War,’ which helped to move the war towards ending slavery. Despite his astute political decisions, he was a terrible army commander. His defeats at Big Bethel and Bermuda Hundred are prime examples of his military ineptitude. Besides his poor leadership qualities, he also had many suspicious financial dealings while in command of New Orleans and the Union Department of Virginia and North Carolina.

POWDER BOAT SCHEME

When Butler received his assignment, he knew that Fort Fisher was the largest earthen fortification in the world. Rather than be encumbered by a lengthy siege, he formulated the Powder Boat Scheme. While Butler was serving at Bermuda Hundred, an ammunition barge was exploded by a Confederate secret agent on August 9, 1864, at City Point, Virginia. City Point was the primary supply base for the Army of Potomac during the siege of Petersburg. The blast killed and wounded 184 people, destroyed docks, buildings, and other barges, causing $4 million in damage.

Butler believed that a similar type of explosion could knock down the walls of Fort Fisher. Against naval ordnance experts’ advice, but, with President Lincoln’s approval, Butler proceeded with his scheme. Admiral Porter thought it was an “experiment worth trying.”

So, USS Louisiana was selected to carry the explosives. This gunboat was built at Harlan & Hollingsworth yard in Wilmington, Delaware, in 1860. The screw iron-hulled steamer, armed with five cannons, was purchased by the US Navy on July 10, 1861.

Louisiana’s first action was receiving the surrender of Chincoteague, Virginia, on October 14, 1861, as well as capturing numerous Confederate schooners. Then the steamer participated in several US North Atlantic Blockading Squadron expeditions in North Carolina waters, including the 1862 Roanoke Island Campaign and the capture of New Bern.

Butler selected Louisiana to deliver 215 tons of gunpowder to Fort Fisher. The vessel was re-confirmed while in Hampton Roads, and was towed south by USS Sassacus beginning December 13 to Beaufort, North Carolina. There the final tons of powder were loaded, and the powder boat was towed 75 miles south to the Cape Fear.

NAVAL ACTIONS

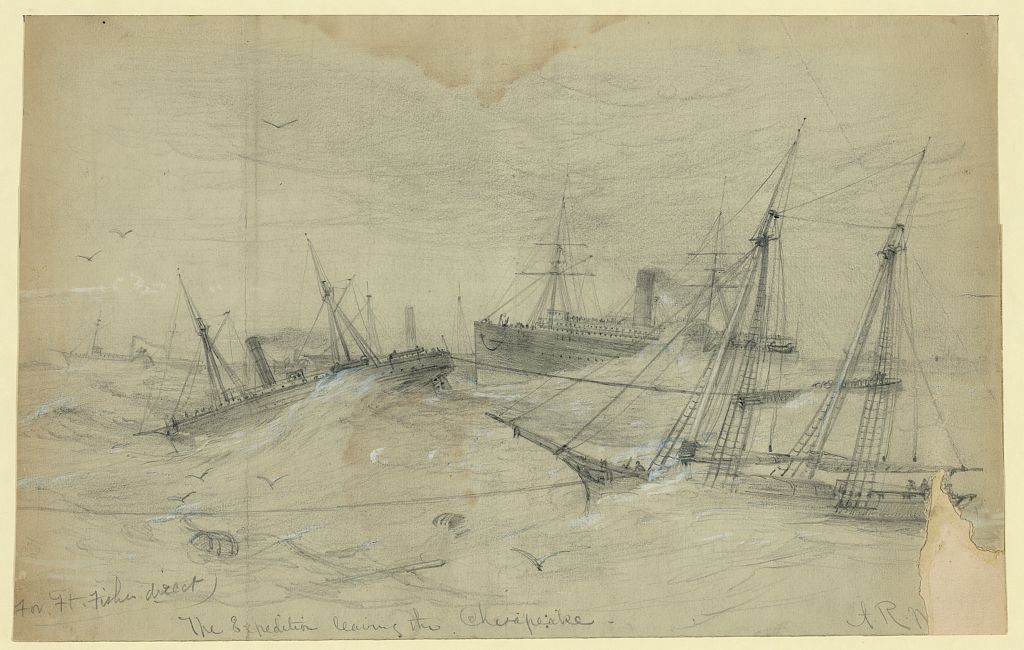

The fleet was assembled in Hampton Roads, Virginia, on December 10, 1864; however, a harsh winter storm delayed the fleet’s departure until December 14. Butler’s transports had already left Virginia and arrived off the Cape Fear River’s New Inlet on December 15. The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron did not arrive until three days later. Porter had assembled a fleet of 57 ships, mounting over 600 cannons. Upon the squadron’s arrival, the weather deteriorated, and Porter sent the transports back to Beaufort. Porter advised Butler to return to Cape Fear on December 23. Butler replied that his troops would arrive on December 24.

Instead of waiting for Butler’s arrival, Porter initiated the attack. That day, Porter’s ships fired almost 10,000 shells into Fort Fisher: but, with little effect. The naval bombardment only damaged four Confederate cannons and inflicted 23 casualties. Meanwhile, the Federal fleet suffered 45 injuries from exploding Parrott rifles. Fort Fisher’s artillery had direct hits on three Union ships. As the evening approached, Porter decided to send Louisiana to position before the fort. The bomb ship was towed by USS Wilderness and reached to within 250 yards of the beach. (Note: this distance is disputed. Some accounts state the powder boat was anywhere from 500 yards up to a mile off the shoreline.)

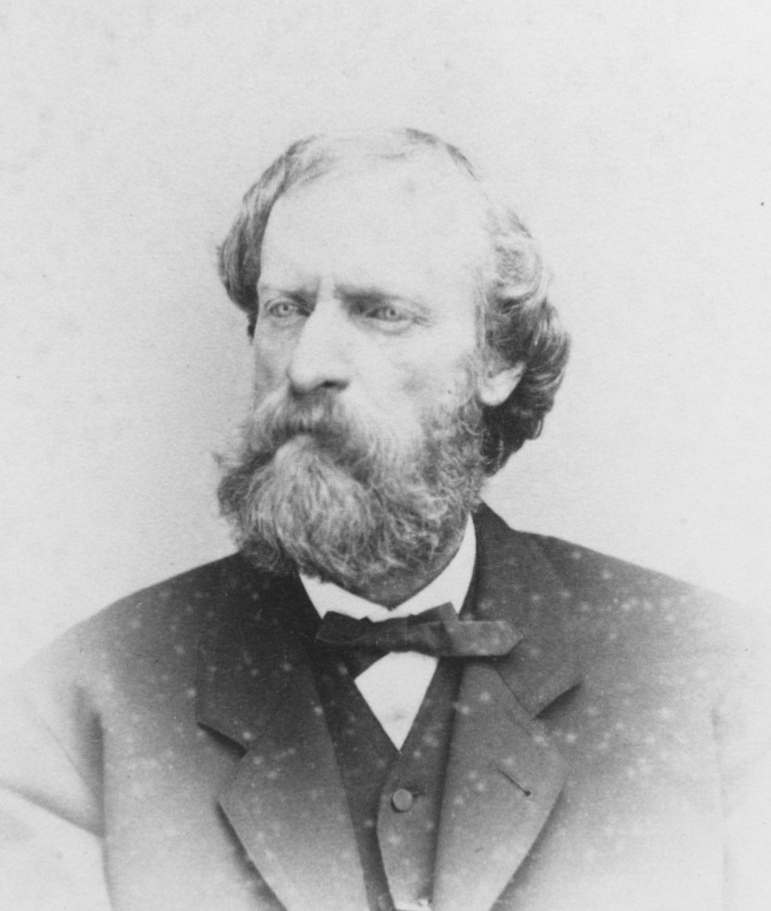

Union naval officer Alexander Rhind, former commander of the ironclad USS Keokuk and steam screw frigate USS Wabash, and some volunteers rowed to Louisiana and lit the fuses and started a small fire in the aft cabin. They then quickly rowed back to Wilderness. Porter, fearing the explosion would be so powerful that it would knock down houses in Wilmington, took his fleet 12 miles out to sea. While the fuses failed to detonate the charges at the appointed time, the wood fire eventually ignited the powder and the bomb ship blew up at about 1:40 a.m. on December 24.

A mighty flame reached up the night sky which quickly turned into a huge, dark sulfurous cloud which drifted out to sea. The powder was defective and Fort Fisher’s defenders hardly thought anything had occurred. Porter, unfazed by this failure, continued his bombardment of the fort, firing another 11,000 rounds into the earthwork. But the range was too far to make any major impact on the fort.

ADVANCE AND RETREAT

Butler and some of the transports arrived late afternoon on Christmas Eve. The rest of his command came the next morning. The landing of Brigadier General Adelbert Ames’s division was achieved without difficulty. Ames then prepared to assault the fort. Butler, however, was beginning to lose his nerve. The Union general thought that the Louisiana explosion had warned the Confederates about the impending attack, and that the naval bombardment had not destroyed Fort Fisher’s land face defenses. Furthermore, Butler had received intelligence indicating that Major General Robert Hoke’s 6,000-strong division had just arrived at Wilmington from Virginia and would soon be in position to attack the Union’s rear. Faced with worsening weather conditions, Butler decided to withdraw his troops on December 27 in heavy surf and return to Hampton Roads.

CONQUERING HERO … (NOT)

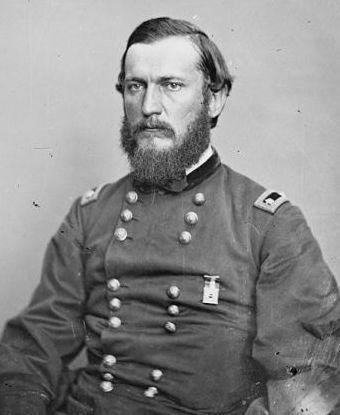

When Butler returned to Virginia, Grant confronted the failed general and fired him for not following orders. Butler’s military incompetence had finally overwhelmed his political connections. Nevertheless, Grant was determined to capture Fort Fisher. He named Major General Alfred H. Terry to take command of the expeditionary force and return to the Cape Fear. He made it clear that Terry was not to return until Fort Fisher was captured.

Excerpted from A History of Ironclads: The Power of Iron Over Wood, John V. Quarstein. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2006. Available in the Museum’s Web Shop: https://shop.marinersmuseum.org/a-history-of-ironclads.html and Confederate Goliath: The Battle of Fort Fisher, Rod Gragg. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1991.