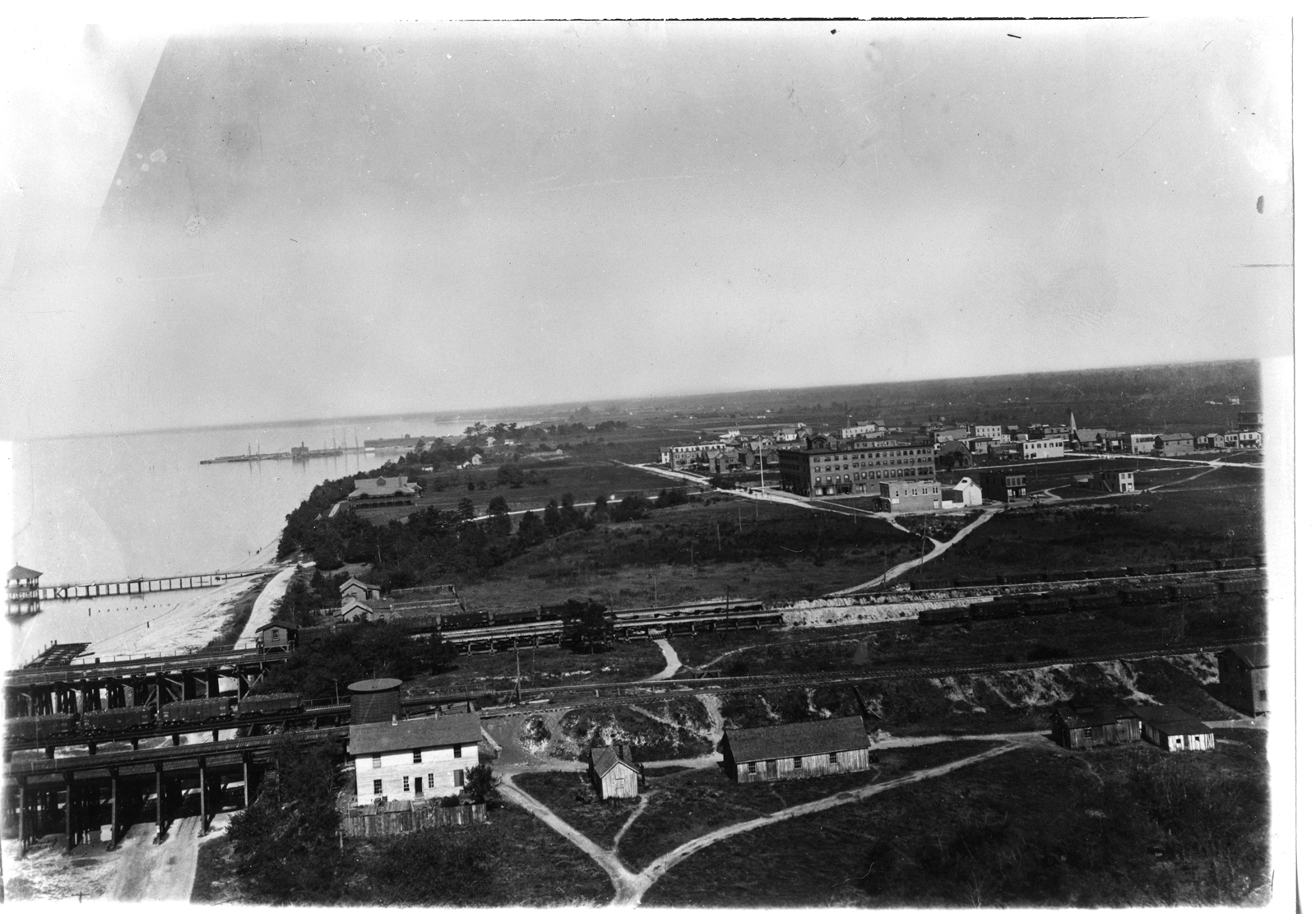

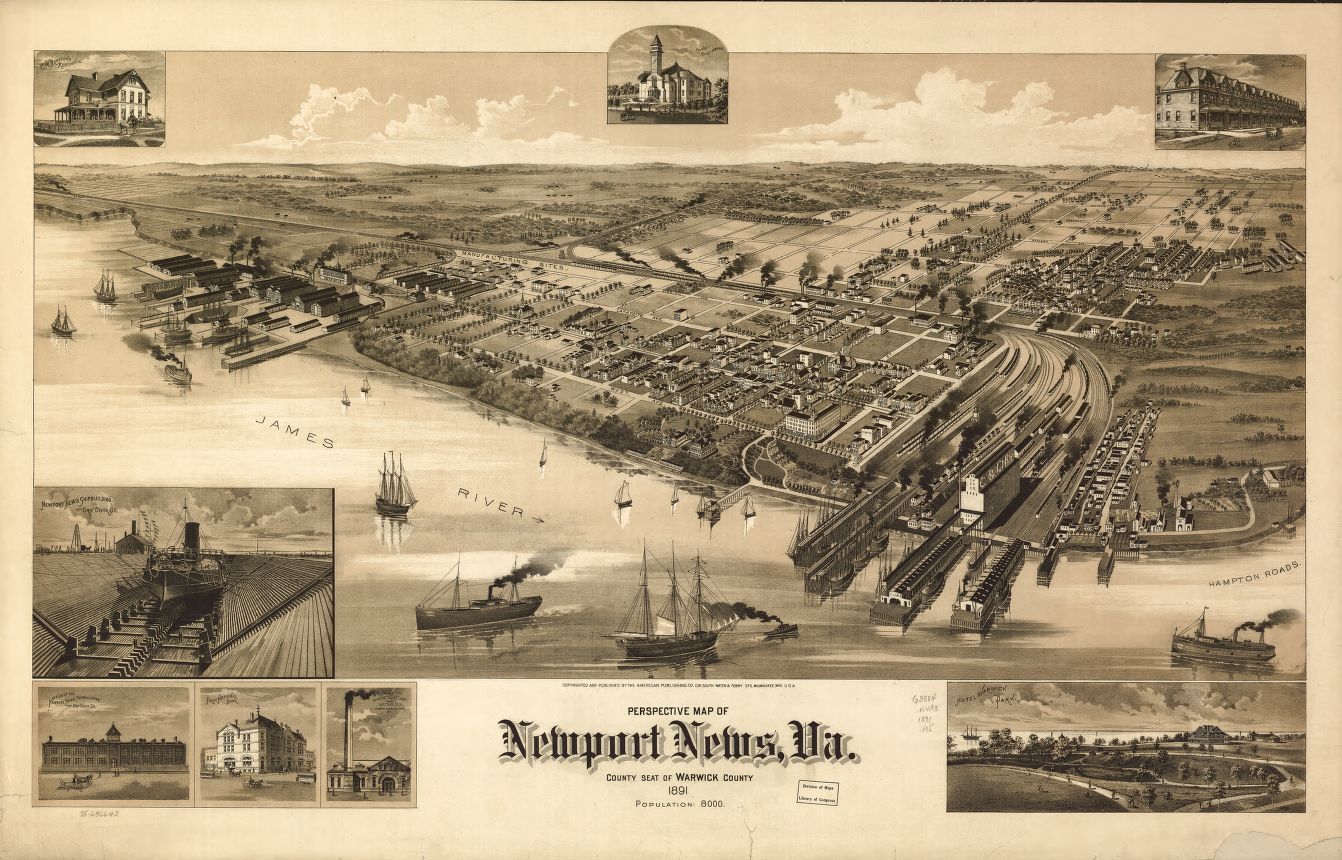

Today, Newport News is over 119 square miles and has a population of over 179,000 people, making it the fifth most populous city in Virginia. That is certainly nothing to sniff at, but, in 1930, Newport News did not extend southeast from Skiffes Creek. It was a concentrated area – only 4 square miles – centered around Newport News Point. The rest of the area that is now Newport News was various villages in Warwick County. Personally, I care most about Morrison (the area where the Museum and Park are), but Hilton, Stanely, Denbigh, ya know all those neighborhoods that still exist, were there, too.

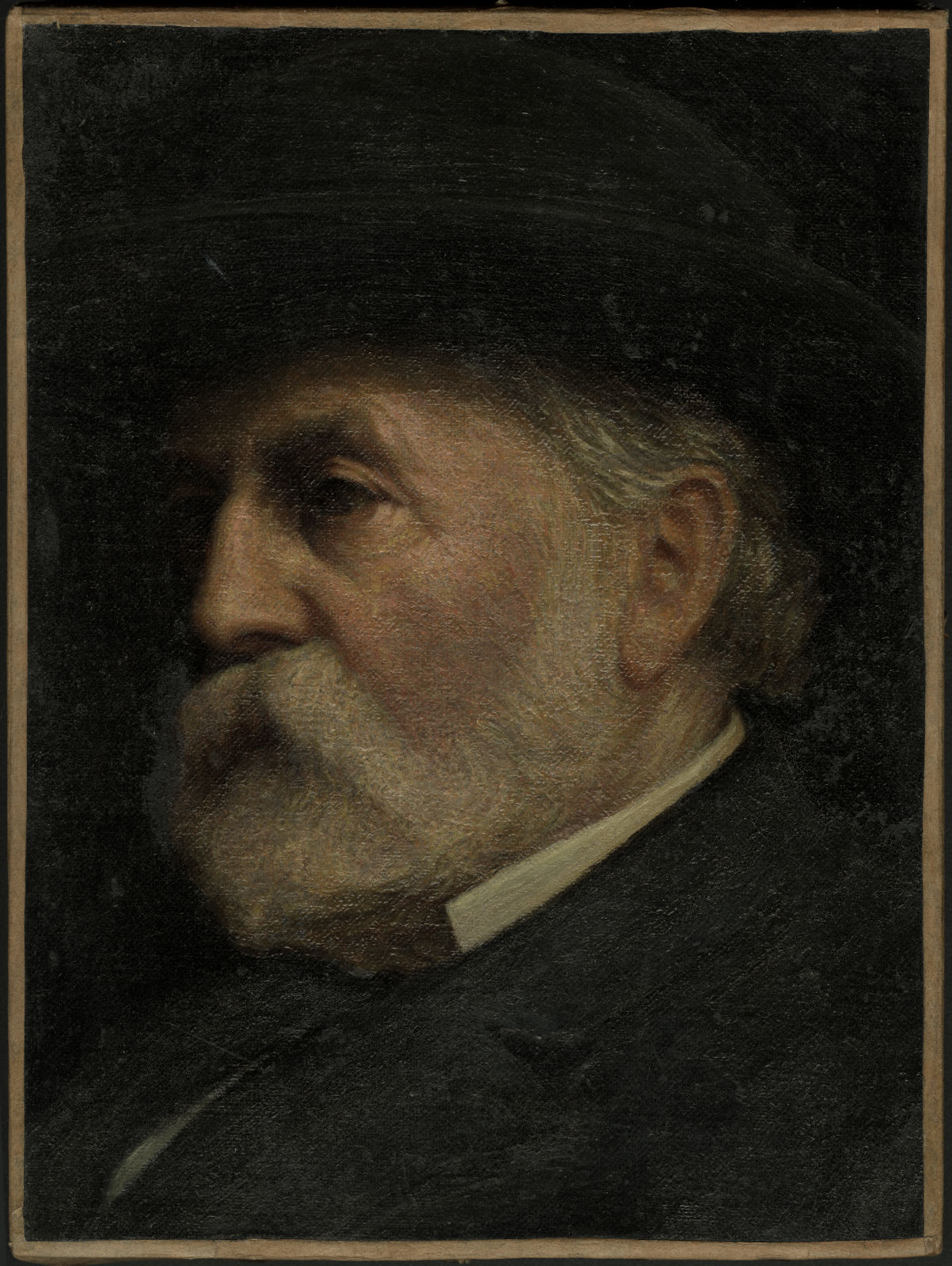

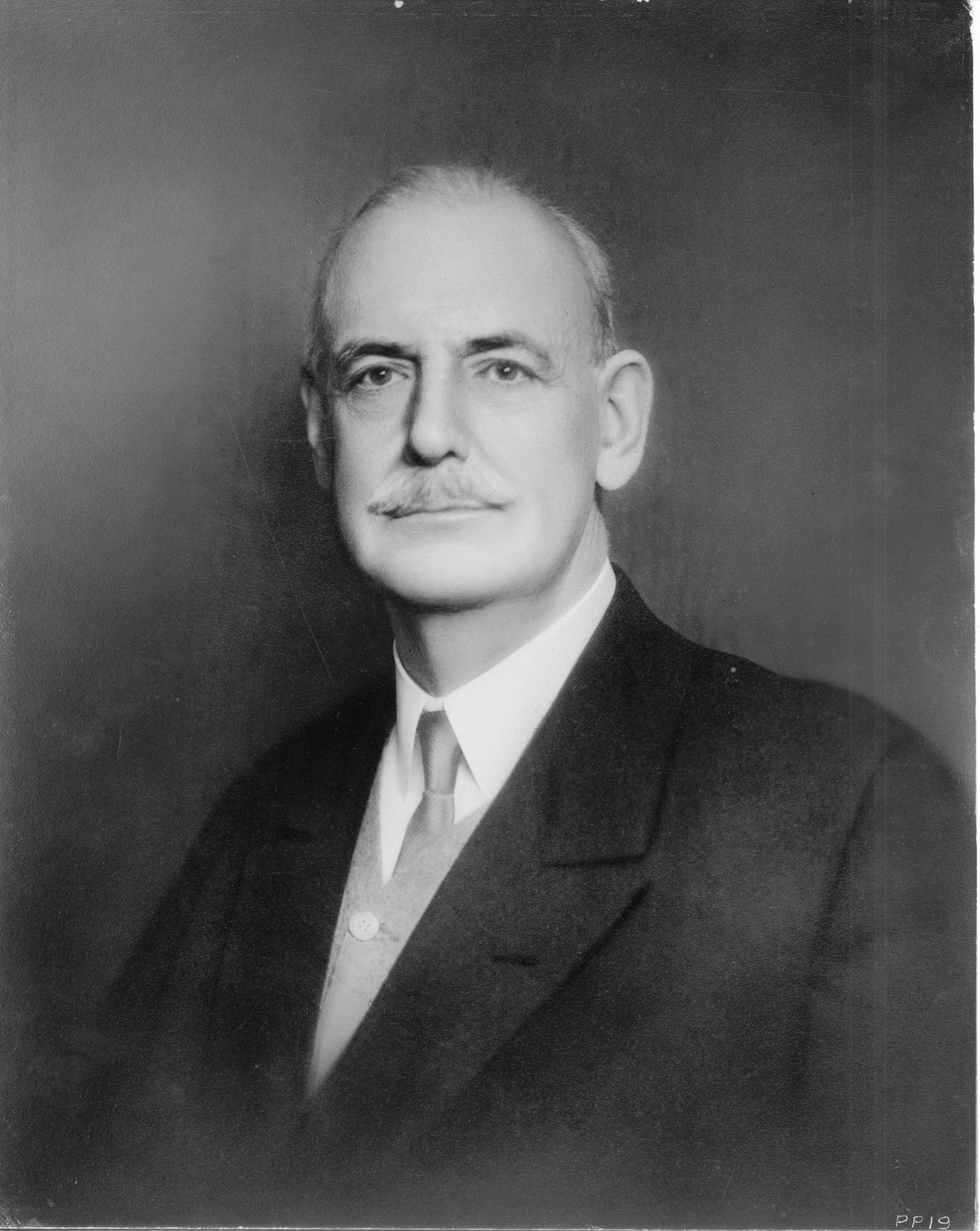

Collis P. Huntington (1821-1900)

Often remembered as one of the “Big Four”, Collis Potter Huntington, was a railroad magnate. Most famously he helped form, and was president of, the Southern Pacific Railroad, but in 1869, Huntington also bought the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Railway with the purpose of extending a single railroad line from coast to coast. His chosen Eastern terminus was Newport News, VA. The *dramatic* (rumored) explanation for this choice was that his mistress was in Richmond, but there was a very practical reason for this decision (too).

To quote the man himself (1800):

There is a point [Newport News] so designed and adapted by nature that it will require comparatively little of the hands of man to fit our purpose. The roadstead, well known to all maritime circles, is large enough to float the ocean commerce of the world; it is easily approached in all winds and weather without pilot or tow; it is never troubled by ice and there is enough depth of water to float any ship that sails the seas and at the same time is so sheltered that vessels can lie there in perfect safety at all times of the year.

Huntington continued to make investments on the Peninsula, starting the Old Dominion Land Company, in 1880, which he used to secure the property for the railroad. C&O Railway then constructed the Peninsula Extension, which ran from Richmond to Newport News Point. The first train ran on this line in 1881 and connected the extension to the Southern Pacific Railroad, which ultimately made a 4,000-mile continuous route from San Francisco to Newport News.

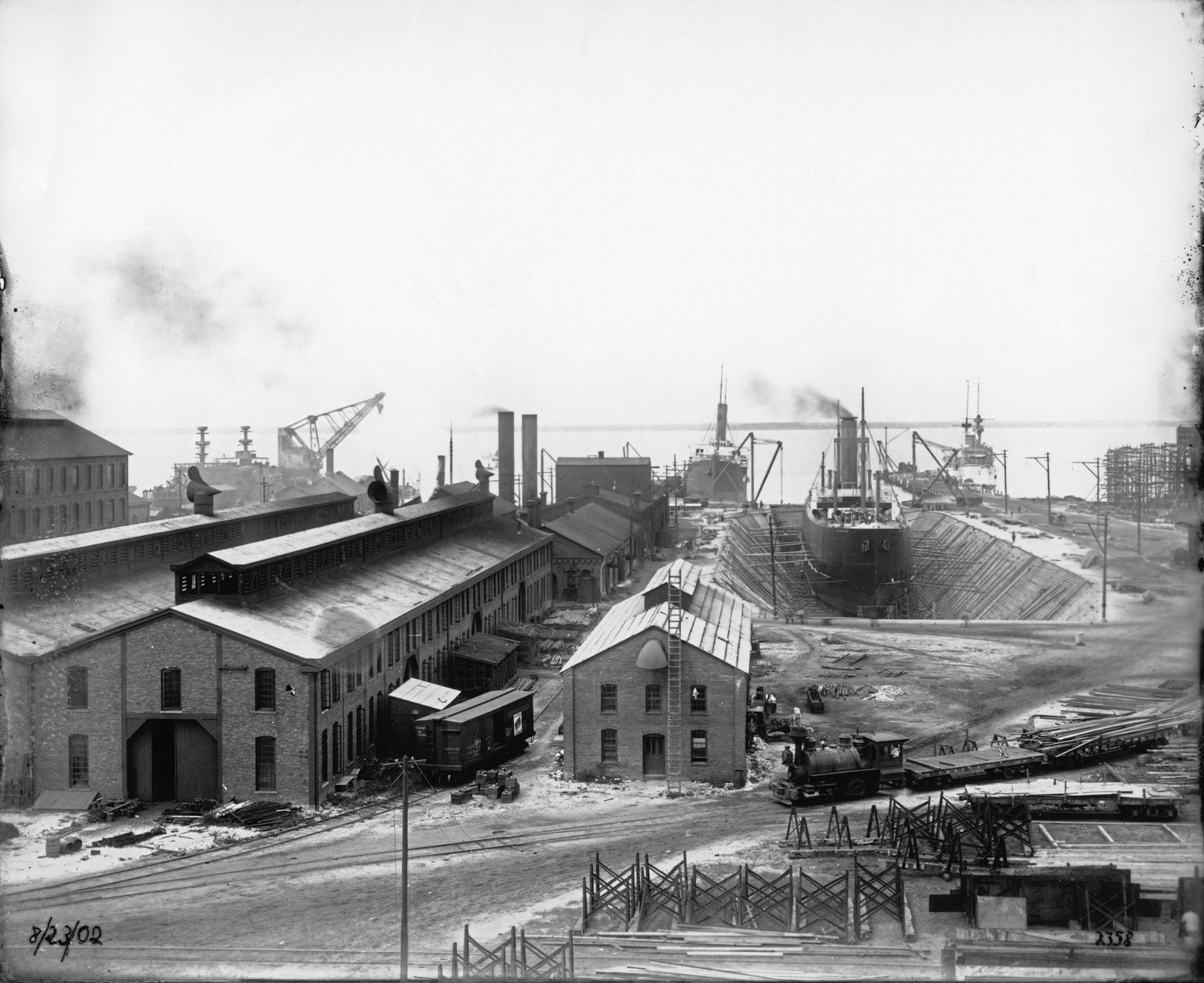

On the Peninsula, Huntington also bought Causey’s Mill Pond and some surrounding land for both railroad purposes and for other business ventures. For example, he thought that Causey’s Mill Pond would one day be a retaining pond for the city’s water supply (fun fact: this Mill Pond is WAY too small to be the city’s water supply). Finally, in 1886 Huntington began construction on the Chesapeake Dry Dock and Construction Company. This opened in 1889. Today, it’s name is Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company.

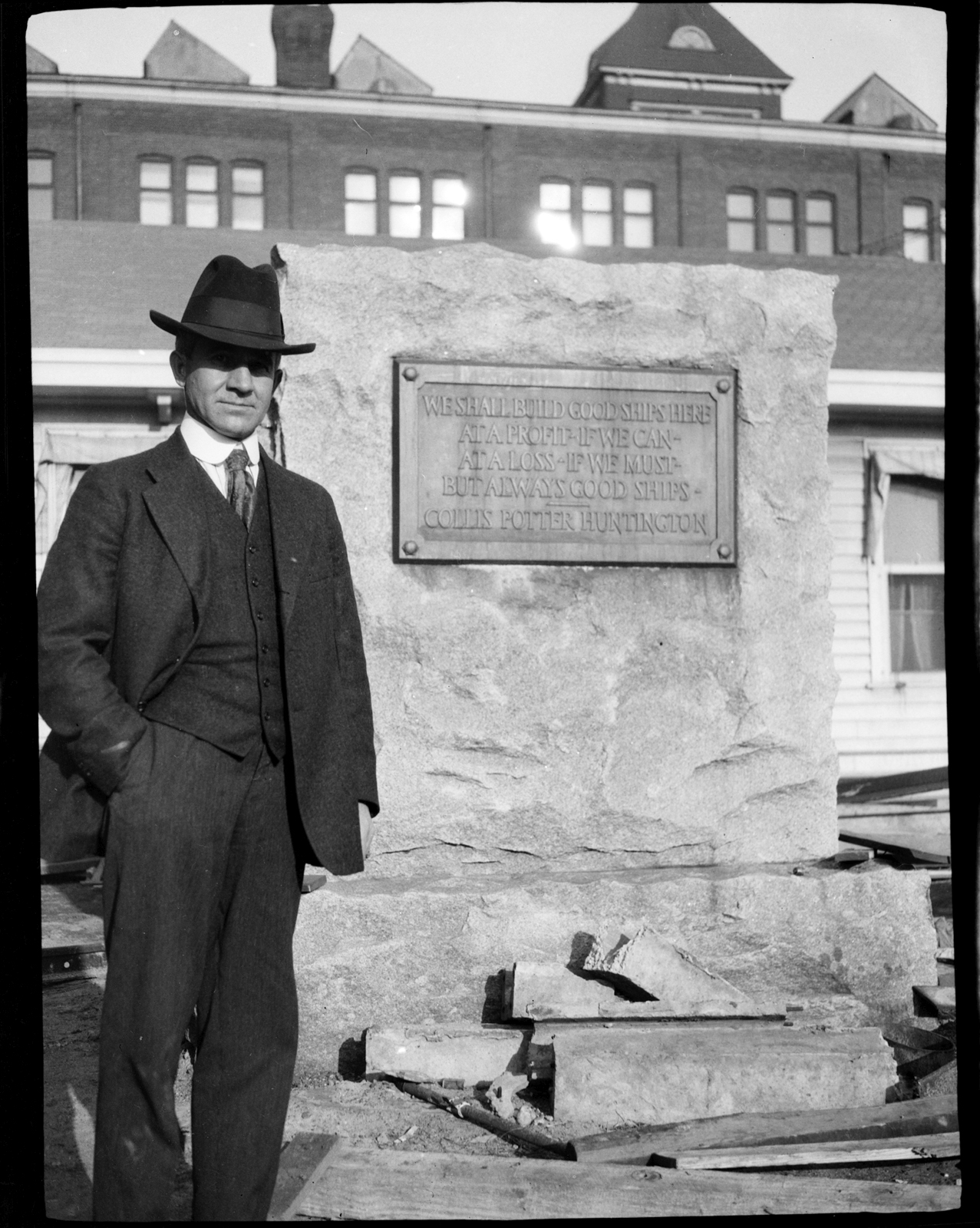

Even though he started this venture very late in life (he died the following year), he saw it as an essential venture because of his overseas coal trade. Did you know that the Peninsula is the largest US coal export location? It became a very successful venture. He famously said, “We shall build good ships here; at a profit, if we can; at a loss, if we must; But always good ships”. In fact, the first vessel served was Puritan, a monitor-class vessel (there are ties to the Museum’s collection everywhere).

How does this tie to the Museum? Collis Huntington’s son, Archer M. Huntington (1870-1955), became a well-respected philanthropist and investor in many cultural institutions. While he was mainly interested in other things, Archer wanted to dedicate a museum to his father’s legacy. See where I am going?

The Village of Morrison

The 1930 census tells us that in that teeny tiny, 4 square mile city – Newport News – there were 34,417 people; while the 65 square mile Warwick County, with all its villages, only had a population of 8,829 people. To give some perspective, that means that every person in Newport News, theoretically, had just over 3,200 square feet of city space to themselves (a really good size house); while in Warwick County every person had over 200,000, theoretical, square feet to themselves (approximately 4.7 acres). By 1929, Morrison news was lumped into “News from Hilton and Vicinity” in the local newspaper, the Daily Press.

Also, based on 1929 voter numbers for Warwick County, we can predict that Hilton Village was larger than Morrison, which was in turn larger than the Denbigh or Stanley precincts. These population numbers were down from the 1920 census, but the economic events of late 1929 surely had an effect on that (what economic events of late 1929?, you ask…keep reading!). Predictions forecast these places becoming huge population centers for the area, though – and they did. By 1950, there were over 42,000 people in Newport News and over 39,000 people in Warwick County (an astounding 450% increase in population!).

Okay, you made it through all the statistics, congrats! Here are some other, less number-y, facts about Morrison. Originally called Gum Grove, because of all the Gum trees in the area, the name for the Village of Morrison changed in 1881, to commemorate Colonel J.S. Morrison, a construction engineer for the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway, working on the Peninsula Extension. They put a train station in Morrison, which was (unsurprisingly) a pretty big deal at the time. In 1883, the town established a post office and in 1906, a public school opened. A high school was added in 1926, which (for you local readers) became Warwick High School, in 1946.

During World War I, Camp Morrison opened as an Embarkation point for U.S. Army Air Corps and Balloon Corps personnel and equipment. It shut down in 1919 after debarking the same personnel and equipment. But, was still a popular Boy Scout camping spot a decade later.

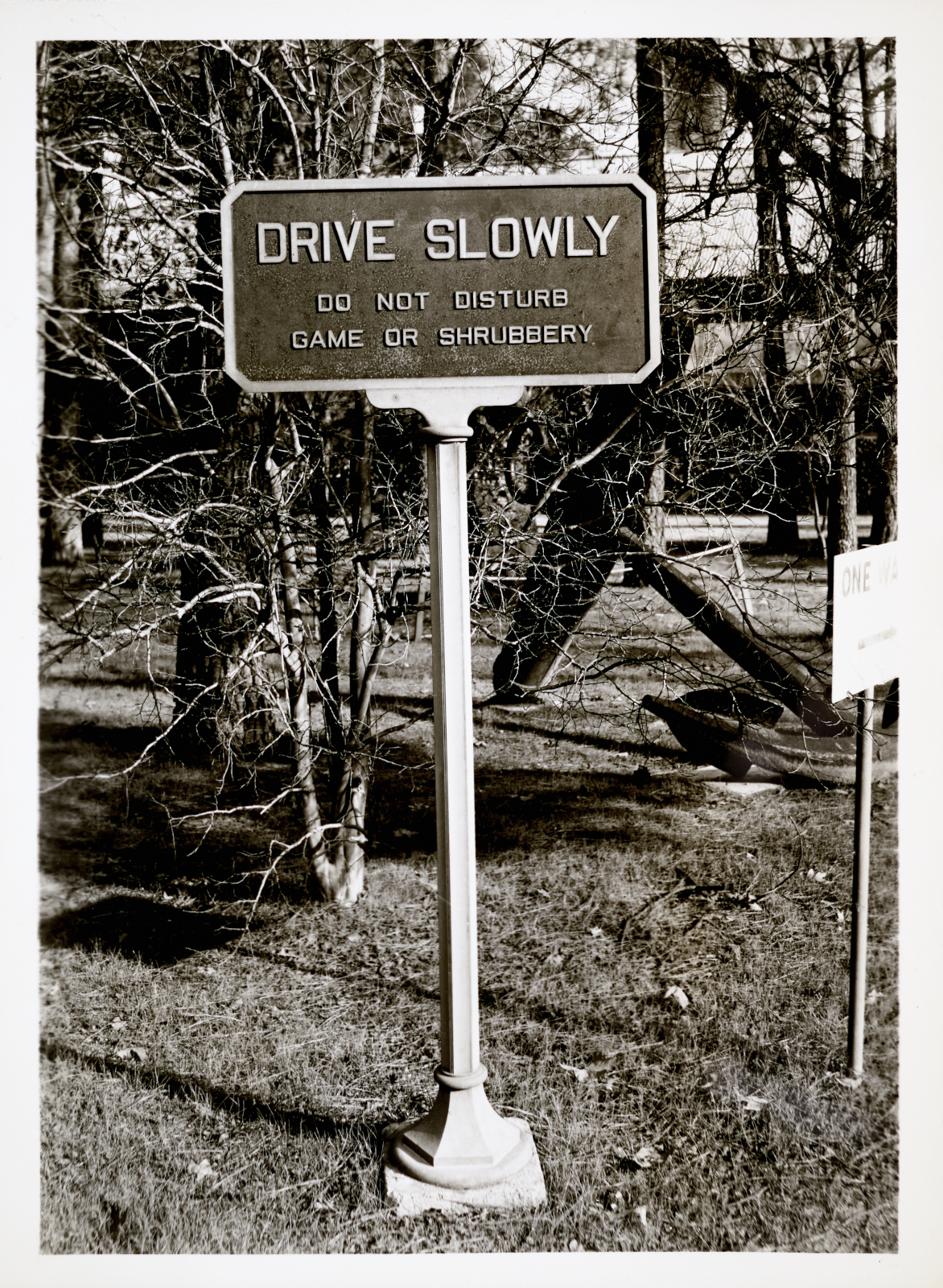

The town was focused around the train station (also unsurprising), but many tenant farmers and landowners had large tracts of land outside of the Village. In the grand scheme of things, most of the town was “new”; only a couple of historic buildings along the James River – including Causey’s Mill – remained. Because of Waters Creek, there was a large area of marshland at the edge of the town. A highway (now Warwick Boulevard) ran through, too, from Richmond to Newport News. The Morrison stretch of road was particularly known for its sharp curve which caused many an accident, but the local government was trying to get that fixed.

Jumping ahead, and just to give more perspective: Over the years, several municipality changes occurred. First Warwick County was incorporated as the City of Warwick in 1952, and in 1958, the City of Warwick joined the City of Newport News. Thus, Morrison ceased to exist, and, like the other villages in Warwick County, it became a neighborhood – Gatewood (at present). There are still a few 1920’s and 1930’s houses in Gatewood. There is even one from 1919! But the neighborhood really grew up in the 1940’s. Thanks, Zillow.

What happened in the USA in 1929-1930?

It is rather shocking, to me, that the top headline for the Daily Press on January 1, 1930, was “Banks of City Set New High Mark in Business For 1929 – One of Most Prosperous Years in History Closed by Local Financial Institutions – Dividends Show Growth of 10% During Period – Slight Decreases in Deposits and Interest; Condition Temporary, Opinion” (Headlines in 1930 were ridiculously long…and subtitles were maxed out). This headline was followed by several others in the same vein – “Pessimism has no place in Programs of Nation’s Heads – Economic Records of Closing Year Indicated Continuation of Expansive Activities, Leaders Believe. – HAIL 1929 AS THE GREATEST OF ANY PEACE-TIME ERA – Resume of Progress for 12 Months Shows Manifold Agencies at Work” and “Vast Development for Newport News Seen by the Mayor – Jones Thinks That The Next Five Years Will See Greatest Expansion in Peninsula’s History – FERGUSON OPTIMISTIC CONCERNING SHIPYARD – Freight Rate Victories, Shipbuilding, New Industries and Tourists Important” (I wasn’t kidding about rambling headlines).

This is a lot of good news and positive outlook considering that in October 1929 the stock market, which until that point skyrocketed, free fell; starting the “Great Crash”. October 24, 1929, or “Black Thursday” was, infamously, the first real day of panic, when investors sold over 12 million shares of stock. Government officials, at first, believed this crash to be a simple fluctuation in the market, and after the panic in October, the dow, which had dropped almost 200 points in less than two months, began to rise again, before the prolonged crash in May 1930.

I would further like to clarify that this news was reported in the Daily Press, and did have effects in this semi-rural area of Virginia. On October 25, 1929, the stock market crisis was front-page news. The headlines read, “No Cause Seen For Government Action in Stock Overturn – Agencies at Washington See No Necessity for Interference of Statement in Wake of Sensation Orgy…” (there is more, but, again, these headlines are long!), “Reaction to Giant Splurge in Market Shown in Wall St. – Famous Financial Thoroughfare, Ordinarily Quiet After Work Hours, Ablaze With Light Far Into Night”, and “Wildest Stock Orgy in History Sweeps Mart Into Tumult – Most Terrifying Stampede on Record Recorded as Almost 12 Million in Sales run Up Before Day’s Close – Most Hectic Scenes Since War-Day Panic – Millions are Reaped in Fantastic Trading; Record 50 Percent over Previous High Mark”.

All this, and still, the outlook in Newport News and Warwick County was positive. In fact, “Newport News and the Virginia Peninsula greet the New Year [1930] with the brightest prospects in many years… unless unforeseen obstacles arise, the next five years should see the greatest progress and prosperity in our history”. Of course, the Great Depression was, most definitely, an unforeseen obstacle, because people didn’t see the October 1929 crash as an impending sign.

The Mariners’ Museum and Park – why here? why then?

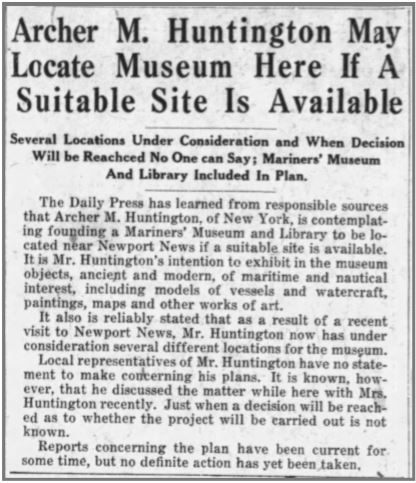

By the end of January 1930, there was clear, public, discussion about bringing a maritime museum to the Virginia Peninsula. Of course, private discussion of the prospect started earlier than that. Legislation had to be passed to dam Water’s Creek, and properties were bought in late 1929.

Why build a museum?, you may ask. That was Archer Huntington’s whole thing. While he was most interested in Spanish culture, he mostly wanted more culture on the whole. He built the Hispanic Society of America, in New York City; this Museum, dedicated to his father; a sculpture garden in South Carolina, for his wife; and offered property and investment to many cultural entities, like the American Geographical Society and the Heye Foundation. The Huntington’s were really interesting people, check out the next blog in this series for more on this subject!

Why here?, you may also ask. With the areas projected growth, Collis Huntington’s influence and investments in the area (there was a high school, road, and several clubs and organizations named in his honor here already), and Archer Huntington’s inheritance of land here; it is pretty easy to see why this was his chosen location for a museum. Rockafeller was also working on restoring Colonial Williamsburg at the same time, presumably ensuring tourist interests in the area.

Why a nautical museum?, you may ask, too. Collis Huntington built the shipyard is the clear, short answer. A longer explanation includes Homer L. Ferguson’s, the shipyard’s president, involvement in museum planning and implementation. In fact, Ferguson also became the Museum’s first president. Collis Huntington’s influence on the area’s shipping, and the close ties between the shipyard and the Museum, makes the subject matter easily understandable.

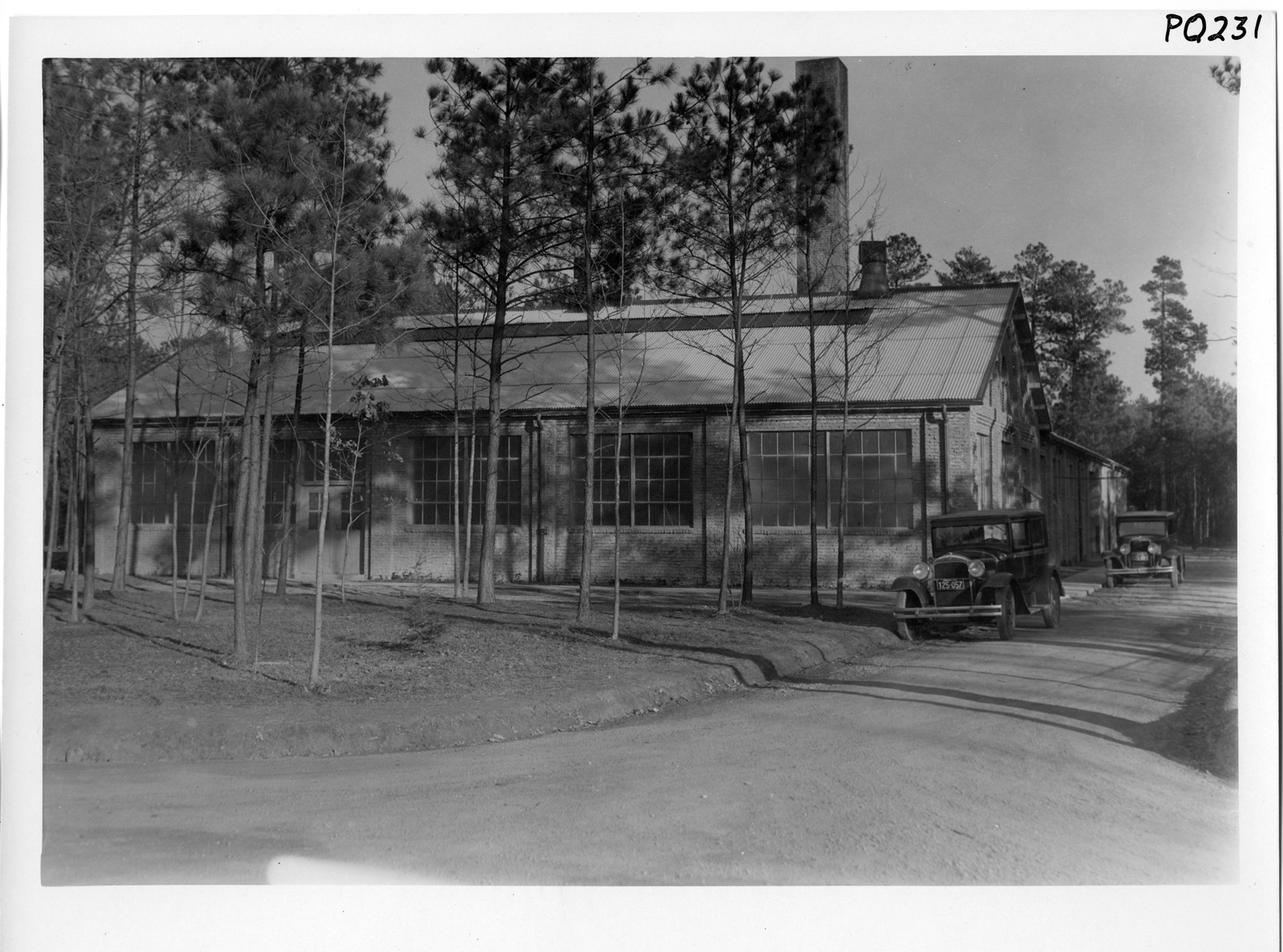

Why 1930?, you may, finally, ask. Whether or not the philanthropist realized the Great Depression loomed just around the corner; starting, and continuing to build, a museum in 1930’s American seems like an odd choice. But, honestly, Archer Huntington’s commitment to building this institution was (and still is) endearing, incredibly admirable, and (at least for me) highly appreciated. There were clear budget shortfalls and focus changes – some of which you will hear about in upcoming anniversary blogs (and, one of my favorite facts, the Museum’s building was originally built and used as a storage shed).

In 1935, Huntington sent his last check to the Museum; the Great Depression hurt everyone, even this ultra-wealthy man, but he tried to use his money for the public good. He built a lasting cultural institution. He bought large tracts of land, many of which did not have current residents. Don’t worry, he continued to lease lands to the tenants for some time, too, so even they weren’t displaced without care. He began collecting locally, buying nautical related goods from the Chesapeake Bay area, before sending buyers to other parts of the globe. And he employed at least a few more individuals in a time of crisis.

Pretty cool, right? Now you know why here, why maritime, and why 1930. I hope this introduction to Morrison at the time is helpful as we continue to share stories about building the Institution and Park with you.

References Cited

Daily Press. Newport News Virginia. 1929-1930. <https://www.newspapers.com/search/#lnd=1&dr_year=1929-1930&t=1773&oquery=1929-1930> (accessed June 1, 2020)

Newport News. “History of Consolidation: Newport News Celebrates 50 Years of Consolidation 1985-2008”. <https://www.nngov.com/282/History-of-Consolidation> (accessed June 1, 2020).

Encyclopedia Britannica. “Great Depression”. <https://www.britannica.com/event/Great-Depression> (accessed June 1, 2020)

Encyclopedia Britannica. “Stock market crash of 1929”. <https://www.britannica.com/event/stock-market-crash-of-1929> (accessed June 1, 2020).

Encyclopedia Britannica. “Collis P. Huntington: American Railroad Magnate”. <https://www.britannica.com/biography/Collis-P-Huntington> (accessed June 1, 2020).

The Hispanic Museum and Library. “Archer Huntington”. <http://hispanicsociety.org/about-us/history/archer-huntington/> (accessed June 1, 2020).

Corporation of Newport News, Virginia. “The Old Dominion Land Company and the Development of the city of Newport News”. <http://cdm15904.contentdm.oclc.org/ui/custom/default/collection/default/resources/custompages/odlcexhibit/index/index.html> (accessed June 1, 2020).

Decennial Census: 1900-1990. “Population by Counties”. <https://www.census.gov/population/cencounts/va190090.txt> (accessed June 1, 2020).

Ferguson Files. Institutional Collection. The Mariners’ Museum Library, Newport News, VA.