I had a little bird,

And its name was Enza.

I opened the window

And in-flu-enza.

– Children’s jump rope rhyme, ca. 1918

About 102 years ago, from this very moment when the world is now gripped by the COVID-19 pandemic, a similar plague, known as the Spanish Flu, struck the globe already in the throes of the vicious and destructive World War I. This flu killed between 20 and 50 million people worldwide.

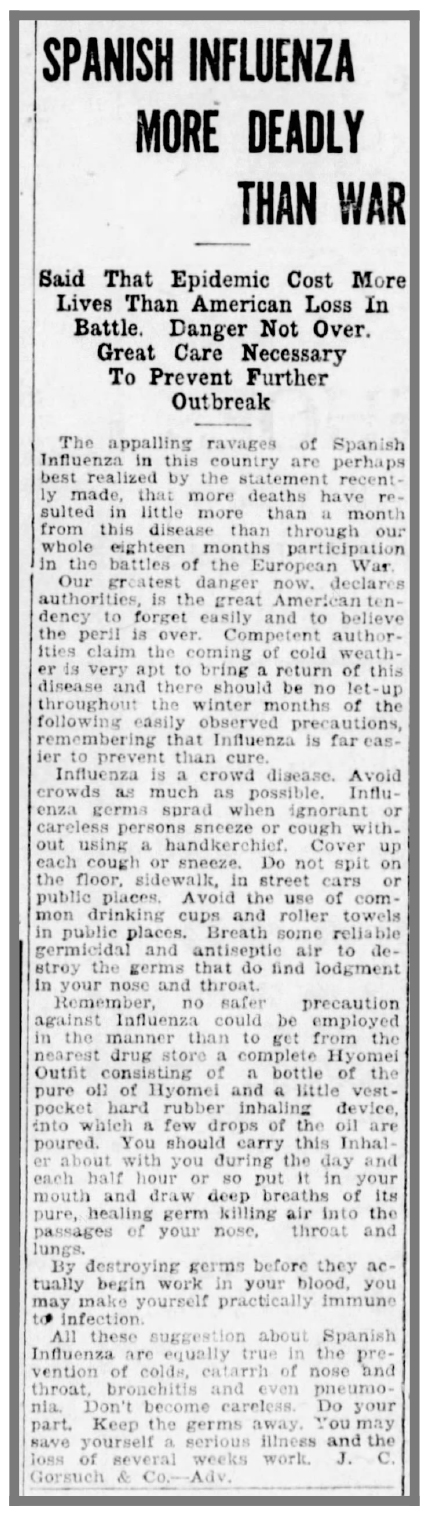

More than 675,000 Americans died during this epidemic that featured three waves of sickness, each one more deadly than the one before. It mostly killed people between 21 and 29 years old. Consequently, it struck soldiers and sailors that were cramped in training camps throughout the nation. The Spanish Flu accounted for more than 80 percent of US combat deaths. Overall, the flu killed more Americans than those who died in World War I, World War II, the Korean War, and Vietnam combined.

Where did Spanish Flu come from?

The Spanish Flu did not originate in Spain; however, it received that name because King Alfonso XIII became extremely ill with the disease. Since much of the world was at war and under censorship, the high profile case of the Spanish king prompted the name. Spain was not involved in the war which enabled news of King Alfonso’s illness to spread throughout the world, as did the disease. Often it was called the ‘Hun plague’ or the German flu as some believed it was the result of an evil plot for the Germans to win the war. Poland called it the ‘Bolshevik disease’ due to the threat of Russian invasion after WWI ended.

The Spanish flu origins have been traced to an Army cook, Albert Gitchell, serving at Camp Funston, Fort Riley, Kansas. Gitchell reported being sick on the morning of March 4, 1918. By lunch time, more than 100 cases were reported at the camp. There were so many sick soldiers within a week that the chief physician had to request a hangar to house all the soldiers who were ill. This first wave of the pandemic quickly spread to the East Coast and then to Europe as the American soldiers moved from camps in the US to those overseas.

The First Wave

The pandemic’s first wave had symptoms of a three-day fever, cough, and runny nose which was followed by a rapid convalescence. No one at that time recognized just how dangerous this flu would be and few precautions were taken. The medical community was ill-prepared to handle this epidemic. Many doctors were poorly trained and some even refuted ‘germ theory.’ Doctors just could not identify how to treat the disease. Most of the work was achieved by nurses and they could only provide comfort to their patients. Some people suggested various remedies, including patent medicine and aspirin. The US Surgeon General recommended that flu victims take 30 grams of aspirin a day. Health officials now know that any dose over four grams a day is unsafe. Accordingly, many deaths were caused by aspirin poisoning.

Not understanding the disease left the medical profession helpless and people sought various quackeries to combat the disease. They just tried to cope with the illness as best they could, and, almost like a miracle, cases dropped to almost zero by August 1918.

Along Come the Second and Third Waves

The Spanish Flu’s second wave hit the United States in September 1918 and was extremely deadly. Of every 1,000 infected, generally 800 had severe flu symptoms, and 200 had lung complications of which 120 could be considered desperately ill or dying. Regular flu symptoms were accompanied by an extremely high fever (up to 105 degrees), delirium, and muscle aches. This weakened the body’s defenses and allowed the onset of pneumonia, which caused most of the deaths, to set-in. Victims would cough up pints of greenish sputum or a frothy, bloody substance. People basically drowned in their own fluids which turned their oxygen-deprived skin blue.

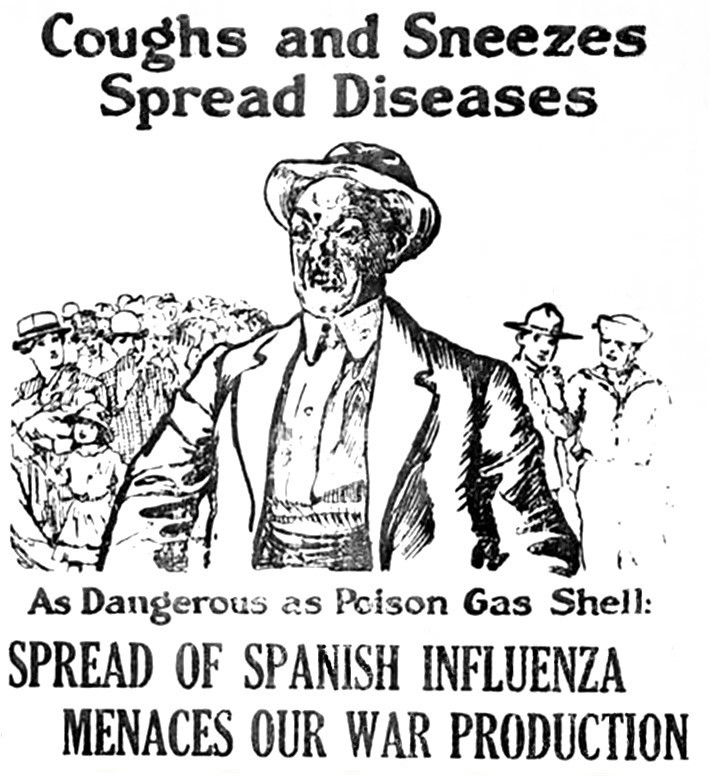

The second wave was fought with more resolute action. Nurses and some doctors recognized that the flu was spread by airborne droplets. So, the Red Cross developed a two-layered gauze mask which was used by many doctors, nurses, police, war work workers, and other civilians.

Other preventative measures were taken. Various diets were suggested. Although unable to stop the spread of the disease, public places, like schools, churches, dance halls and essential businesses, were closed; and public gatherings were not allowed. Hospitals were overwhelmed, morgues were filled to capacity, coffins were scarce, and many vital services were limited. Coal shortages, due to overtaxed transportation networks, left buildings cold, and the lack of heat caused more sickness.

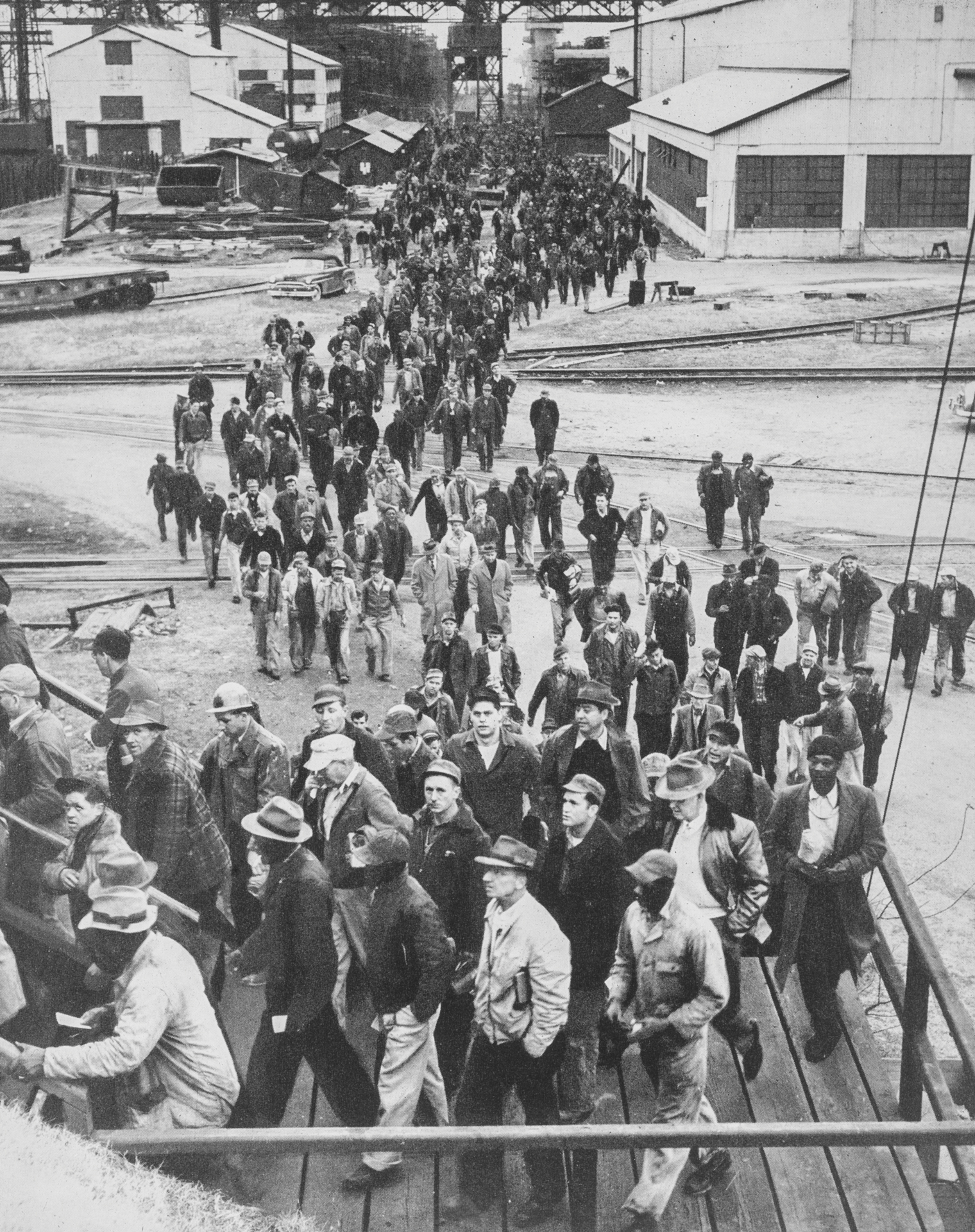

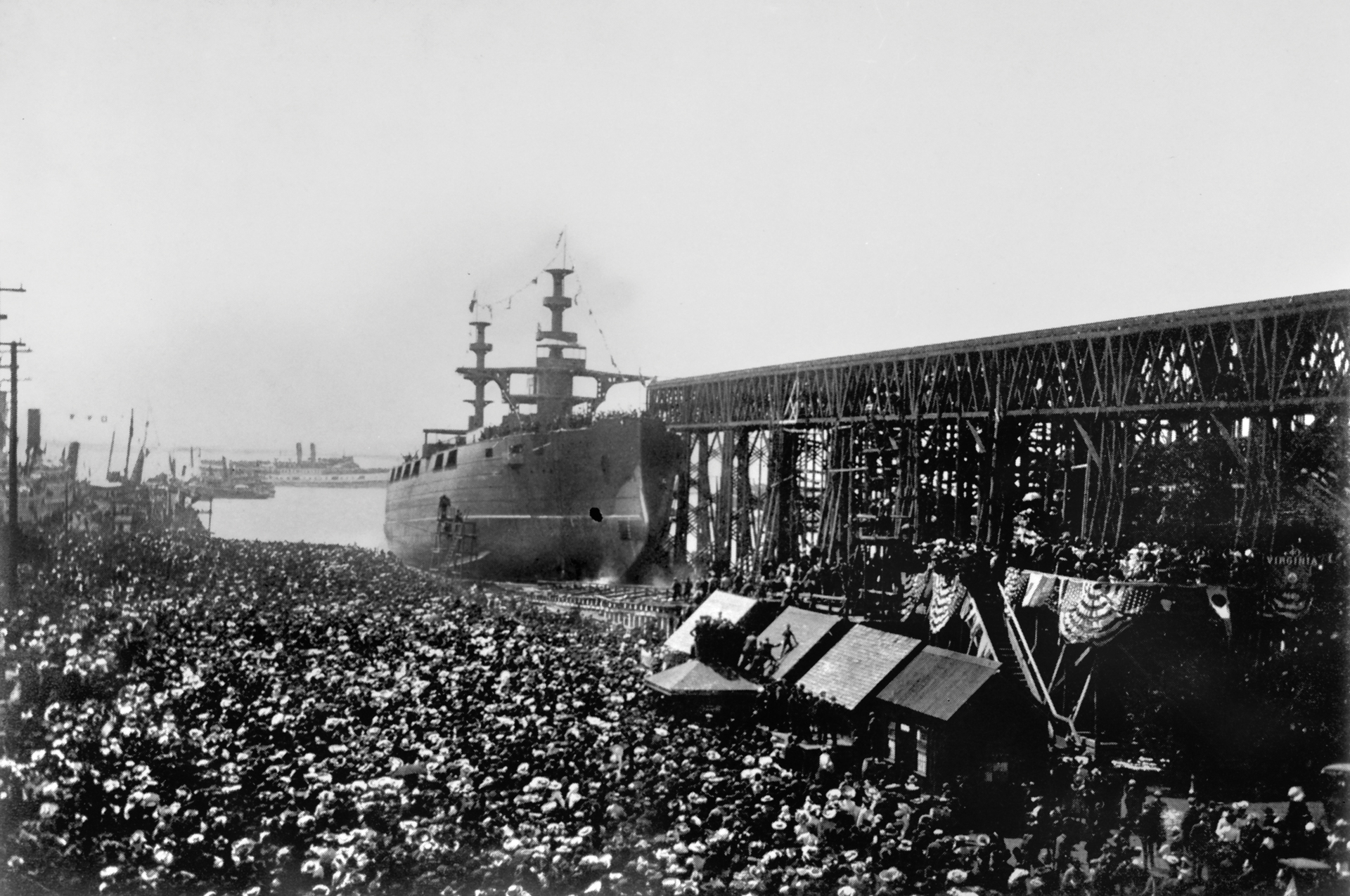

However, it was wartime and the needs of the American military sometimes overruled safety. Soldiers and sailors seemed always in endless lines as they crowded onto ships and into their camps. Shipyard workers had no choice but to do their work to support the war. This caused the flu to spread rapidly. In Europe this wave, and the one to follow, was very deadly. Many note that as the Second Wave struck the German army with such a debilitating effect that it was one of the contributing factors prompting Germany to request an armistice.

The Third Wave was not quite as deadly . Many of the precautions created during the previous waves, were not implemented in the wave that lasted from December; yet it was still impactful.

War-torn Europe was socially and economically weakened due to the conflict war that people died by the thousands. The post-war revolutions only made the flu European death toll rise.

Newport News during the Epidemic

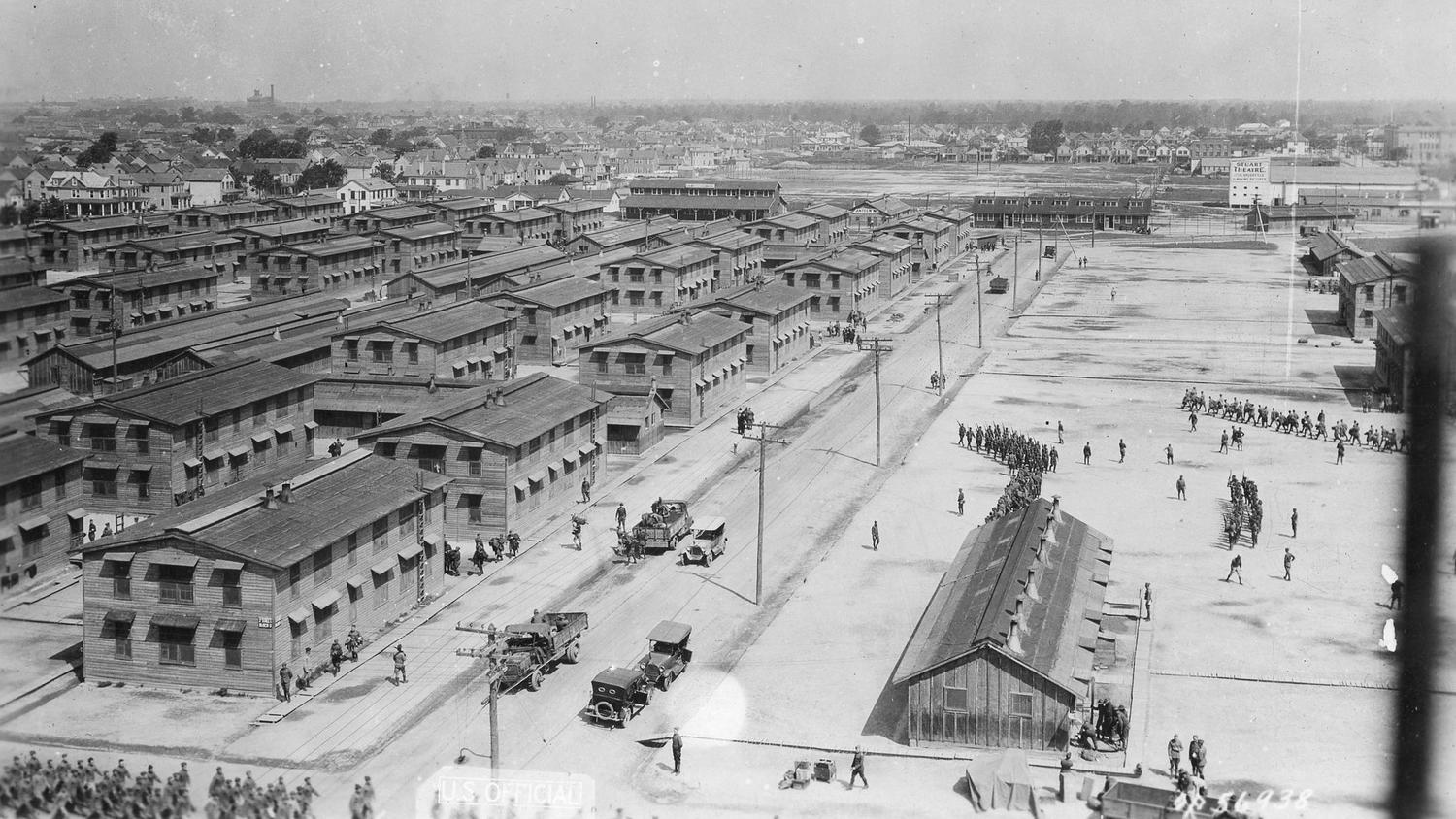

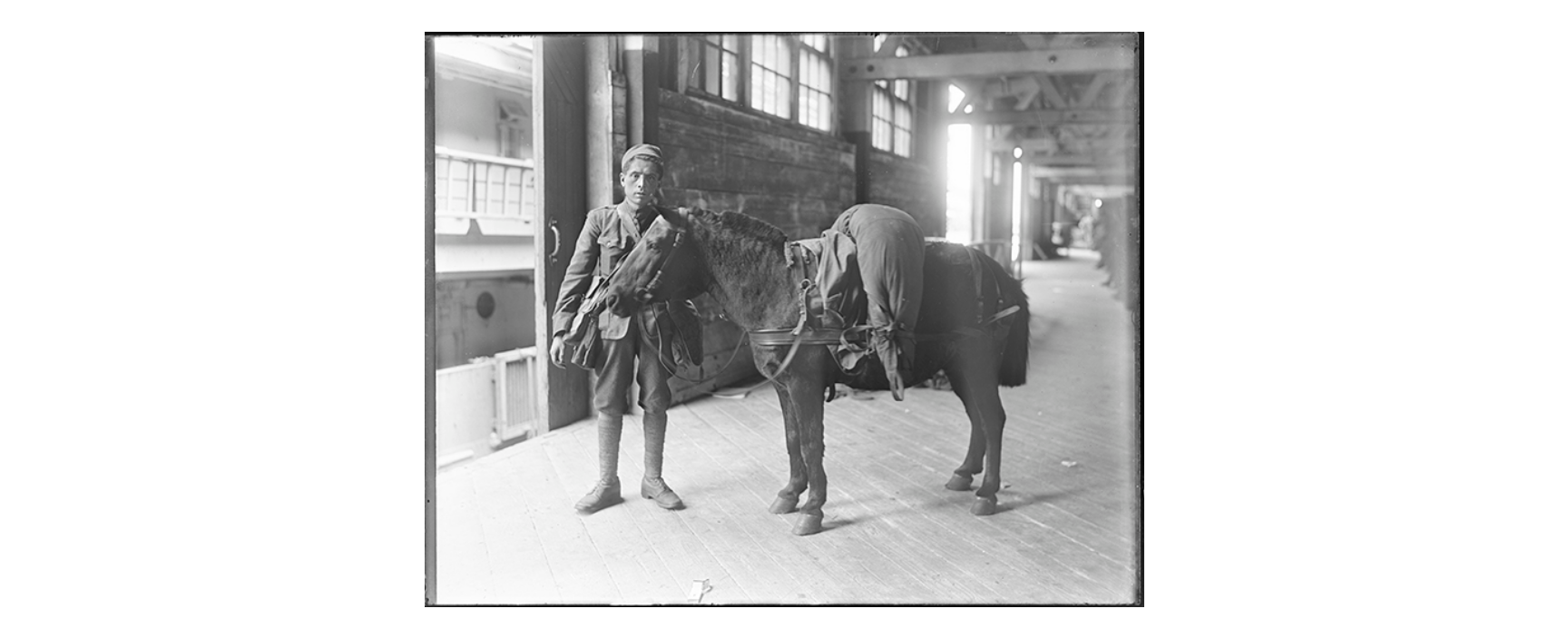

By the end of World War I, Newport News had doubled its population. The city was simply unable to provide all of the housing and services required to support shipyard workers, building construction crews, civilians, and soldiers. Newport News was the headquarters of the Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation and sent 261,820 soldiers overseas during 1918. In August alone, 46,130 troops left the port for France in 145 transports. August also witnessed 438 ships leaving Newport News loaded with horses, mules, and tons of supplies to support the war overseas.

The port was busier than ever and this movement of people through the city in early September caused the pandemic to spread quickly. Nothing seemed to stop the virus. In October, more than 5,000 cases were reported in Newport News. Caskets of flu victims from Camp Stuart, overlooking Hampton Roads, were carried by trucks daily for shipment home. Flu patients at the camp were ‘aired’ in special breezeway wards to help drop the high fevers. This action only caused more deaths. “ The soldiers died like flies out there in the mud,” reported local resident Soloman Travis.

Entire families were overcome with sickness and it was recommended that if one member of the family was ill that they should be isolated in a single room. This was often impossible to achieve. Funeral homes operated around the clock to handle all of the corpses; but it was reported that some of the dead were simply buried in backyards. People sought cures wherever they could look. The Spanish Flu did not seem like a disease to many people; rather, “ more like some diabolical wildfire.”

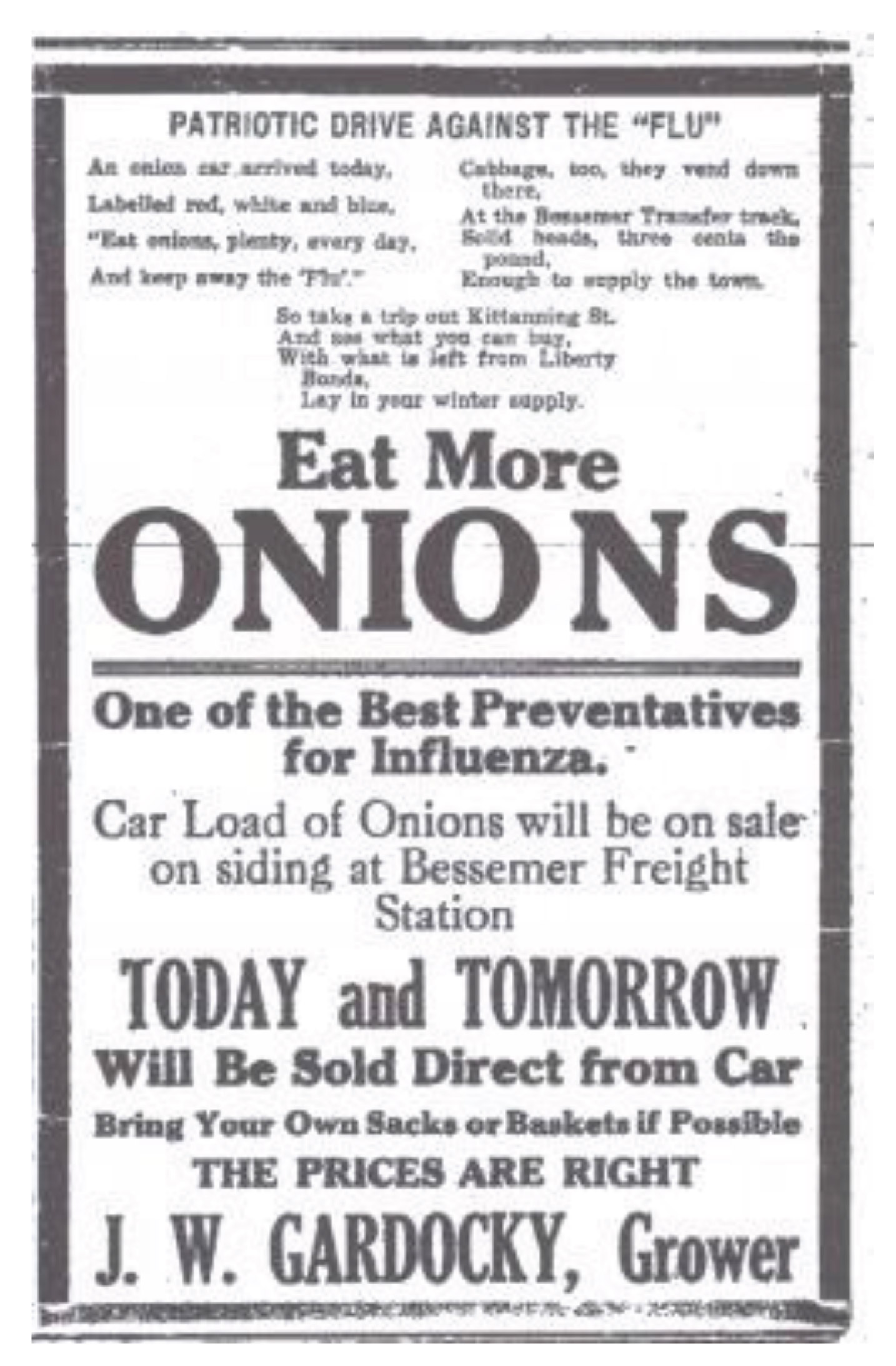

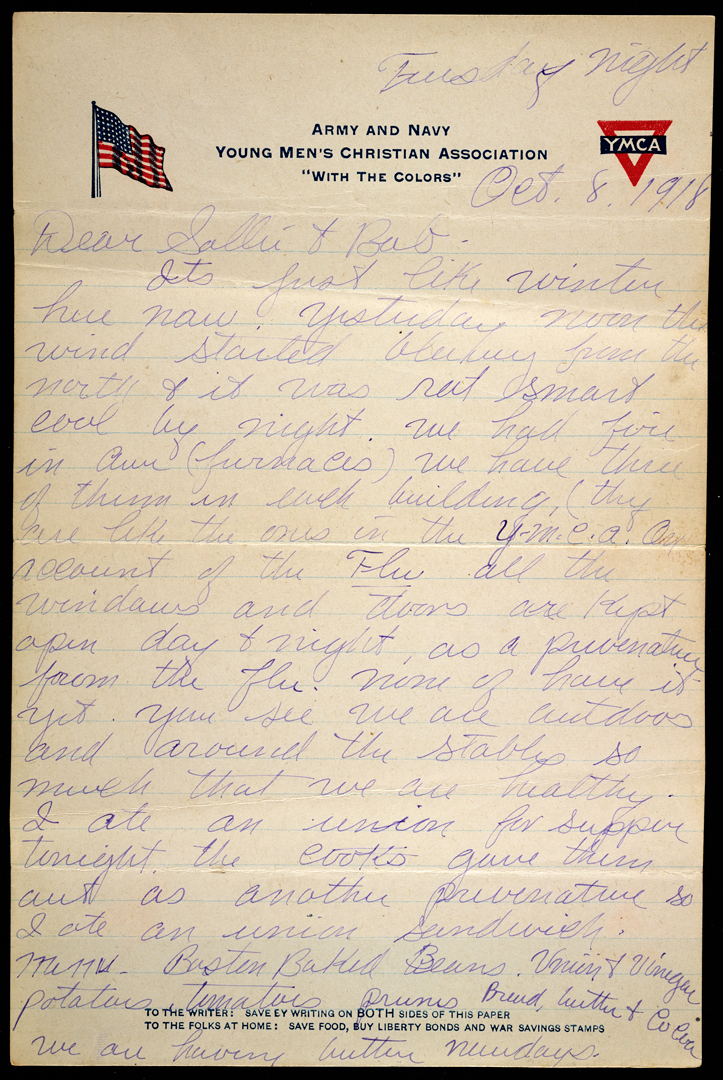

US Army Farrier John J. L. “Joe” Harlin, stationed at Camp Hill, wrote his family on October 8, 1918, that “on account of the flu all of the windows and doors are kept open day & night as a preventative from the flu. None of us have it yet….You see we are outdoors and around the stables so much that we are healthy. I ate an onion for supper tonight. The cooks gave them out as another preventative. So, I ate an onion sandwich….We had company tonight. A man came up and gave us a little talk and told us some stories. He told us not to take any quinine as word came down from Washington that quinine was spreading the flu and for us to take plenty of physic (a medicine that purges, a laxative or cathartic) and drink water.”

Local government struck back against the disease. Movie theaters, dance halls, and hostess houses were closed. The city of Newport News advised that citizens should not get into crowded streetcars; limited access was provided to the courts; churches were closed; and no visitors were allowed in hospitals. Newport News converted the newly completed Walter Reed High School into an emergency hospital and a matching grant was received to combat the illness. Yet, by early November, the flu spike ended and was never again to strike the city with such vengeance.

Norfolk during the Pandemic

Like Newport News, Norfolk was home to training bases, storage facilities, shipyards, and docked warships, all of which had to be manned. The overcrowding made Norfolk a perfect place to spread germs and the accompanying sickness.

There were some who took advantage of the pandemic to push forward their own political or social agendas. Reverend Steinmetz of Norfolk was glad that the dance halls were closed as he believed they were the source of ‘immoral indulgences’ by servicemen that hurt Norfolk’s ability to support the war effort. He said that the dance halls and dances at Armory Hall were especially “heinous,” and that dancing enabled servicemen to meet prostitutes. But, both the military and civilian authorities quickly reopened the dance halls stating that they were well chaperoned.

The second wave appeared in Norfolk (and Newport News) on September 13, 1918. The flu raged through Norfolk like wildfire causing public facilities to close. The first cases were reported in mid-September. During the pandemic 9,000 flu cases were reported in Norfolk and 3,500 cases were recorded at Norfolk Naval Station with 175 deaths.

On October 22, Oregon’s Rogue River Courier published part of a letter from Miss Bernice Umphlette of Norfolk, Virginia, written to her sister. The banner headline read “TERRIBLE DEATH TOLL NORFOLK.” She noted, “ We are having a terrible siege of Spanish Influenza. Really, people are dying by the hundred. They are using school buildings for hospitals and all public places such as barber shops, schools, churches, shows, etc. are closed. The disease is very contagious, but I have not caught it thus far. There are so many dying that the undertaker can scarcely take care of the bodies. The condition is awful, it is like war…”

As in Newport News, the disease was basically gone by November. The town recorded only 273 deaths.

Spanish Flu Comes and Leaves Hampton Roads

By mid-September 1918, the first reported cases of the Spanish Flu were reported. It is no wonder that this disease would strike eastern Virginia as there were just so many soldiers, sailors, and workers coming into the community to support the war effort. Bases and ships had to be built, requiring more workers than Hampton Roads had ever seen before.

The Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation created a need for several new training camps like Camp Eustis and Camp Stuart in Newport News, designed to handle thousands of soldiers heading to Europe. The war was reaching its zenith and shipyards did not stop their important work. Even though between September and November 1918, the community briefly closed down, once the main wave cleared Hampton Roads it was back to business for the region.

Bond drives, Red Cross workers passing out thousands of donuts, and more soldiers and sailors heading out to and from Europe became the norm. It is rather amazing that Hampton Roads did not incur more sickness. Port cities like Philadelphia were badly struck by the disease — from September to December, the town suffered 13,426 deaths. Many of these were attributed to a super spreader event on September 28, 1918. More than 100,000 close-packed people attended a Liberty Loan Bond Campaign parade. Two days later, a hundred people a day were dying of the flu.

Amazingly, Hampton Roads only witnessed about 600 deaths. Once the spike ended in mid-November, schools reopened (students were tested daily for fever through December), and life began to return to normal. Newport News featured Victory parades, celebrations to honor returning soldiers, and numerous Victory Loan Bond drive rallies through June 1919. There was little mention of flu cases. Considering the amount of people who worked in war related industries and the great number of soldiers and sailors passing through Norfolk and Newport News, these communities took precautions when necessary. Citizens considered this as their patriotic duty. The Spanish Flu indicates to us in this age of COVID-19, that history does indeed, repeat itself.

References

Caelleigh, Addeane S. “The Influenza Pandemic in Virginia (1918–1919).” (2020, July 20). Encyclopedia Virginia online. Accessed Dec. 5, 2020. http://www.EncyclopediaVirginia.org/

Daily Press (Newport News, VA). “Spanish Influenza More Deadly Than War,” January 7, 1919.

John J. L. “Joe” Harlin Papers. Collection of The Mariners’ Museum and Park, Newport News, VA.

Parramore, Thomas C. Norfolk: The First Four Centuries. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1994.

Quarstein, John V. World War I on the Virginia Peninsula. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 1998.

Quarstein, John V. and Parke S. Rouse Jr. Newport News: A Centennial History. Newport News, Virginia: The City of Newport News, 1996.

Rogue River Courier (Grants Pass, OR). “Terrible Death Toll Norfolk,” October 22, 1919.

Sharp, John G. M. “The Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 at the Norfolk Naval Shipyard, Naval Training Station Hampton Roads and the Norfolk Naval Hospital.” Naval History and Heritage Command online. Accessed December 2, 2020. https://www.history.navy.mil/