Easy to Overlook

Well, well, well. I’ve definitely done it this time. You’ll hear from museum professionals over and over about the idea of falling down the proverbial rabbit hole. Something captures our attention, and away we go, sometimes spending hours upon hours digging into the topic du jour. It can be anything that causes this condition. It might be a shipwreck, a painting, a moment in time, an exciting person, etc. Sometimes it’s a side dish on a menu. Yeah, you read that right. Come to think of it, though, a side dish might even be too grand a description.

I recently had cause to photograph some of our ephemera (a fancy word for printed memorabilia) from The Baltimore Steam Packet Company. You may be more familiar with their moniker “Old Bay Line.” One of the items I digitized was the menu for the Baltimore Steam Packet Company’s centennial celebration dinner on May 23, 1940. From the menu, it’s safe to assume that it was a grand affair featuring such sophisticated dishes as seafood cocktail, terrapin a la Chesapeake, golden roast pheasant, Maryland Beaten Biscuits, Cen–

Wait. Just. One. Minute.

I’m sorry. Maryland, what now?

A Bit About Old Bay Line

Before we go any further, it seems prudent to know a little more about The Baltimore Steam Packet Company, or Old Bay Line as it was more commonly known. A “steam packet” is a medium-sized steamboat, usually operating on rivers, canals, and bays, in this instance. It ferried mail, typically on a government contract, in addition to freight and passengers. In the latter part of the 19th century, packet lines referred to boats operating on a fixed daily schedule between two or more ports.

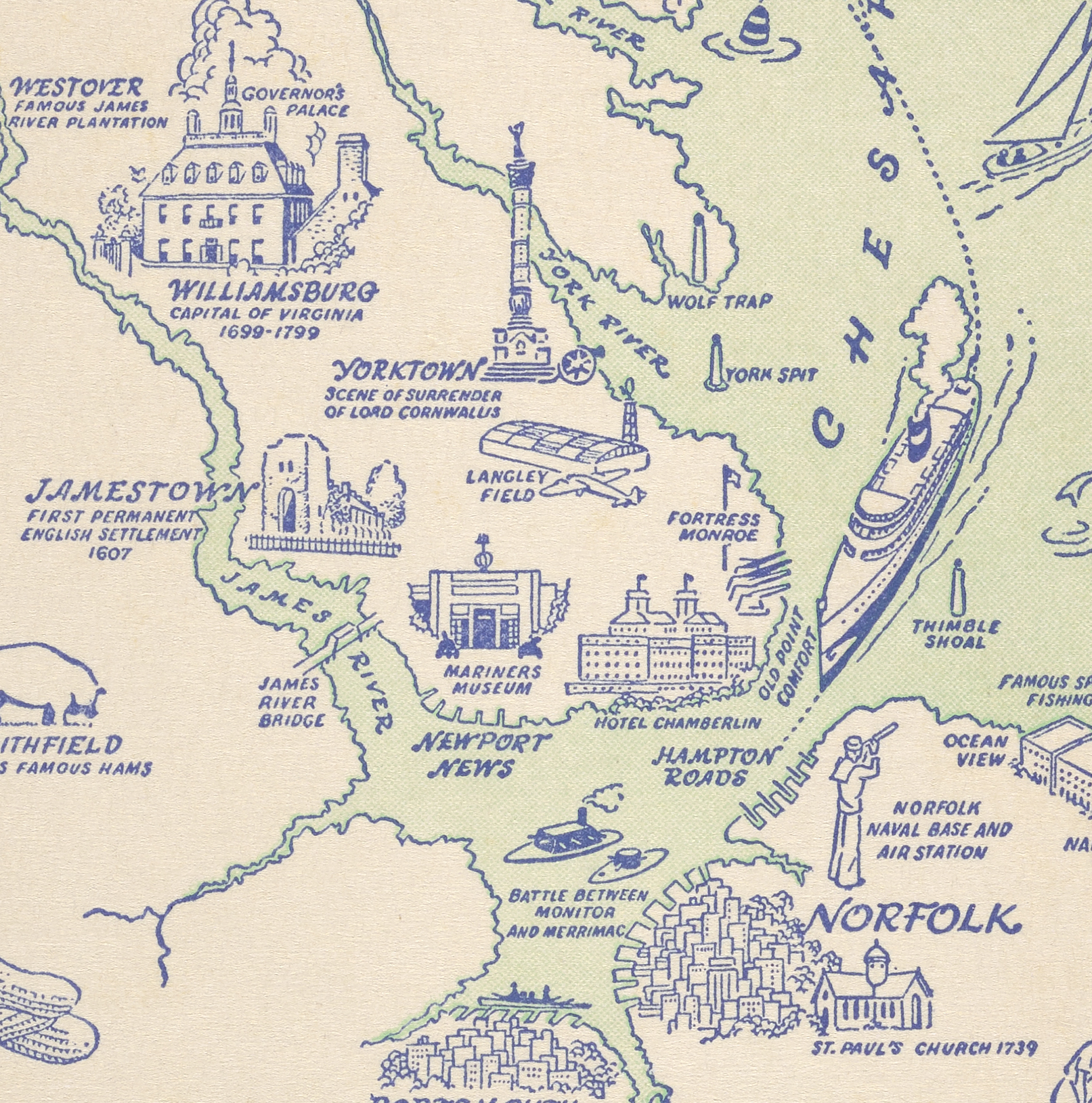

On March 18, 1840, The Baltimore Steam Packet Company was granted a 20-year charter by the Maryland legislature to provide overnight service on the Chesapeake Bay. They began with three vessels acquired from the recently collapsed Maryland & Virginia Steam Boat Company: Pocahontas, Georgia, and Jewess. The Old Bay Line ran predominantly between Baltimore and the “Old Dominion” ports at Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Old Point Comfort (Hampton). It offered daily overnight service, except on Sunday, to both passengers and freight. By 1848, the Old Bay Line’s Herald could make the journey in less than 12 hours.

Based in Baltimore, the Old Bay Line brought together the best of northern technology and engineering with the south’s ease, comfort, and famed hospitality. This seamless blending led to boats that were known for their sophisticated service and steadfast reliability.

So About Those Biscuits?

The Baltimore Steam Packet Company prided itself on serving the best of Chesapeake Bay specialties. That included, at least in the instance of their centennial, Maryland Beaten Biscuits. So what exactly are they?

Maryland Beaten Biscuits are, essentially, a cousin of English naval hardtack. If you’re unfamiliar, hardtack was a simple blend of whole wheat flour, water, and salt. It was mixed and then baked, sometimes upwards of four times, to remove any moisture from the resulting bread altogether. With no water, the flour blocks would last for years and years without going bad. Hardtack was made using whole wheat flour because it provided a good source of protein, vitamins, and calories.

When English settlers came to North America, they brought hardtack with them. It became a staple for survival and the army. It was cheap, easy to prepare, and never went rancid so long as it remained dry. That said, it was not something most people would consider tasty. Hardtack required soaking in coffee, beer, salt water, or any liquid on hand before eating. While dry, it was inedible and was likely to break teeth if you tried.

Cut forward to the 19th century Maryland homestead, and you’ll find a similar problem that requires a slightly different solution. How do you create a simple bread product that can be stored for long periods with no refrigeration, last in the tobacco fields, but, additionally, taste good? Cue the beaten biscuit.

Biscuit Ingenuity

Biscuit Ingenuity

Homestead cooks would have easily had access to the same ingredients required for hardtack; water, salt, and flour. They had the advantage of also having access to another biscuit staple in the form of lard. Lard would have added some flavor, moisture, and more calories to the classic recipe. What they didn’t have easy access to was yeast or chemical leavening. So how do you make these basic ingredients softer and more palatable? Clever home cooks decided to grab a hammer. Or a rolling pin. Or the flat of an ax. Or a baseball bat.

Once you mix all the ingredients into a sticky lump, you remove it from the bowl, place it on a board (or a flattened stump of a tree), and give it a good whack. Well, a lot of good whacks. You must beat the dough between 30 and 60 minutes, depending on how tender you want the resulting biscuits. My favorite description comes from the Delmarva Heritage and Traditions video featuring Barrie Parsons Tilghman and her sister Ellen Hitch. Barrie says the best rule of thumb is “thirty minutes for family and an hour for company.”

Food Science at Work

So, what’s happening to the dough during the beating process? I reached out to Dr. Dennis D. Miller, professor emeritus of food science at Cornell University’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, for answers. “When wheat flour is combined with salt and water and mixed, the gluten in the flour forms a continuous protein network that is capable of trapping air and/or carbon dioxide from leavening agents such as yeast or baking powder,” said Dr. Miller. “This network results in what is called a visco-elastic dough, meaning that it is viscous but will stretch. My guess is that the pounding of the dough will fracture some of the protein network making the length of the protein chains shorter and this will result in a softer final product.”

In traditional yeasted bread baking, you want to use a “strong” flour and knead the dough to create long strings of gluten, the protein found in wheat. These long chains help to trap air bubbles that give the bread its signature webbed texture inside. It also results in it having a more rigid exterior. By beating the dough for as long as possible, you create very short strands of protein and end up with a very soft, very dense final product.

After beating, the dough is rolled into a snake and torn into individual pieces. Each piece should be about the size of a clementine. Each piece is kneaded slightly to smooth it and rolled into a ball. The ball is then poked on top with a fork or a custom pricker to let out moisture, and then they are baked until cooked through but still pale blonde. Traditionally, the biscuits are eaten with butter, country ham, cheddar cheese, or blackstrap molasses. Everyone has their preference, but the neutral flavor of the biscuits allows for plenty of options.

But Did You Make Some?

I attempted to make two batches of Maryland Beaten Biscuits, and, to be honest, I don’t think it went so well. To be fair, I’ve never eaten one before, so all I had to go on was written accounts and the words of people that I’ve spoken to. Don’t get me wrong, they tasted delicious, but the texture didn’t seem to come out the way I had expected. In most accounts, the biscuits are firm on the outside and very dense and soft on the inside. Mine turned out much drier than expected and had a more crumbly texture like a regular biscuit might.

However, it was an interesting and enjoyable process, so I highly encourage you to give it a try. If you are interested in making your own batch, I used Ellen Hitch’s family recipe and followed along with this video:

Family Traditions

The Maryland Beaten Biscuit has remained a staple of Chesapeake Bay families in Maryland. You are unlikely to find anyone making them for Tuesday night’s dinner, but they tend to appear on most holidays and special occasions. Unfortunately, you will not find them commercially produced anymore, either. Orrell’s Maryland Beaten Biscuits, the last commercial biscuit maker, closed its doors in 2013 after the passing of the family patriarch and company founder, Dick Orrell. They are currently working on a documentary project about the company and the tradition of beaten biscuits.

Still, the tradition persists in Maryland communities. Families pass down their biscuit tools like a board, hammer, and pricker. The pricker is an essential part of the making process by letting out moisture, preventing too much rise, and denoting who made the batch of biscuits. Every biscuit maker has their mark. Prickers handed down through families usually have a single point removed to change the pattern for the new maker.

I was fortunate enough to have a call with several people familiar with the making or eating of Maryland Beaten Biscuits. Jan Plotczyk, George Shivers, and Peter Heck, writers for Common Sense Eastern Shore (commonsenseeasternshore.org), sat down with me via Zoom to discuss their ties to Maryland Beaten Biscuits. We had a delightful conversation about the biscuits, and everyone, in turn, shared stories of making them, a family member who would make them, or just enjoying eating them and the comfort they brought. George showed me his family’s biscuit beater and pricker, handed down to him through the generations. Peter recounted a story of his early working days when he would go to the grocery store and get biscuits and country ham for a quick lunch. They all offered sage wisdom on the preparation and recipe for the biscuits and helped to guide me.

A Lesson in Connection

The Mariners’ Museum and Park connects people to the world’s waters because through the waters, through our shared maritime heritage, we are connected to each other. That’s our goal, our hope. I have firsthand seen this play out time and time again. There isn’t an employee at the Museum who doesn’t have a story of connecting with a former stranger because of shared interests, a common hope, or a family story. I have those stories, as well. But this, well, this just solidifies for me how true that capacity to connect really is.

I spotted something small and seemingly insignificant on a single piece of our vast collections. A biscuit I’d never heard of. It was a thread, and when I pulled at it, I found people on the other end. I found a food scientist with knowledge and passion for his job. I found fellow writers excited and eager to share their traditions with me, welcome me into their world, and connect with me. If only for moments, if only through emails or Zoom calls, we came together to share knowledge, stories, traditions, heritage, pieces of ourselves given freely.

That’s the real power of The Mariners’ Museum and Park. That’s the real power of connecting to one another. Food, much like our oceans, has such capacity to bring us all together.