The first combined operation of the Civil War was the capture of Hatteras Inlet. This inlet was used by Confederate gunboats and privateer merchantmen sailing around Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. These Southern commerce raiders’ depreciation was lucrative for the Carolinians; however, Northern losses became so significant that several major maritime insurance brokers demanded something be done about this situation. This prompted the development of the Union’s Hatteras Inlet operation. [1]

North Carolina’s Outer Banks

The North Carolina Sounds reached from the Virginia border to Cape Lookout, the eastern border of North Carolina. Four major inlets could be used to reach the Atlantic Ocean from the Sounds: Hatteras, Oregon, Ocracoke, and Beaufort (Old Inlet). Hatteras Inlet was best situated for commerce raiding. Cape Hatteras was the easternmost point within the Confederacy, overlooking the Gulf Stream. This current was very popular with merchant ships trading between Northern ports like New York, the Caribbean, and South America. Using the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, the Confederates could signal waiting raiders about tempting merchantmen targets. “The enemy’s commerce,” wrote North Carolina governor John Ellis on April 27, 1861, “could be cut off by privateers on the coast of No. Carolina.” [2]

The Need for Coastal Defense

North Carolina immediately set out to fortify these inlets. Beaufort was protected by a brick coastal defense fortification, Fort Macon. Nevertheless, all the other inlets lacked any means of defense to protect them from Union warships. Accordingly, Brigadier General Walter Gwyn was assigned to develop fortifications to guard these important water gateways as commander of Northern Coastal Defenses of North Carolina. Gwyn was an 1822 graduate of West Point. He had resigned his commission to become an international engineer. When the Civil War broke out, Gwyn planned the construction of the Sewells Point batteries defending Norfolk until assigned to North Carolina. [3] Gwyn, however, had few resources at his disposal. North Carolina had raised 22 regiments when the war erupted; yet, all but six were sent to Virginia to defend Richmond, leaving about 1,000 soldiers to defend the North Carolina Sounds. Cannons were also needed to place within forts. These guns had to be shipped from Norfolk via canal and railroad to reach the isolated Outer Banks. Four different forts were planned: Forts Ocracoke, Oregon, Clark, and Hatteras.

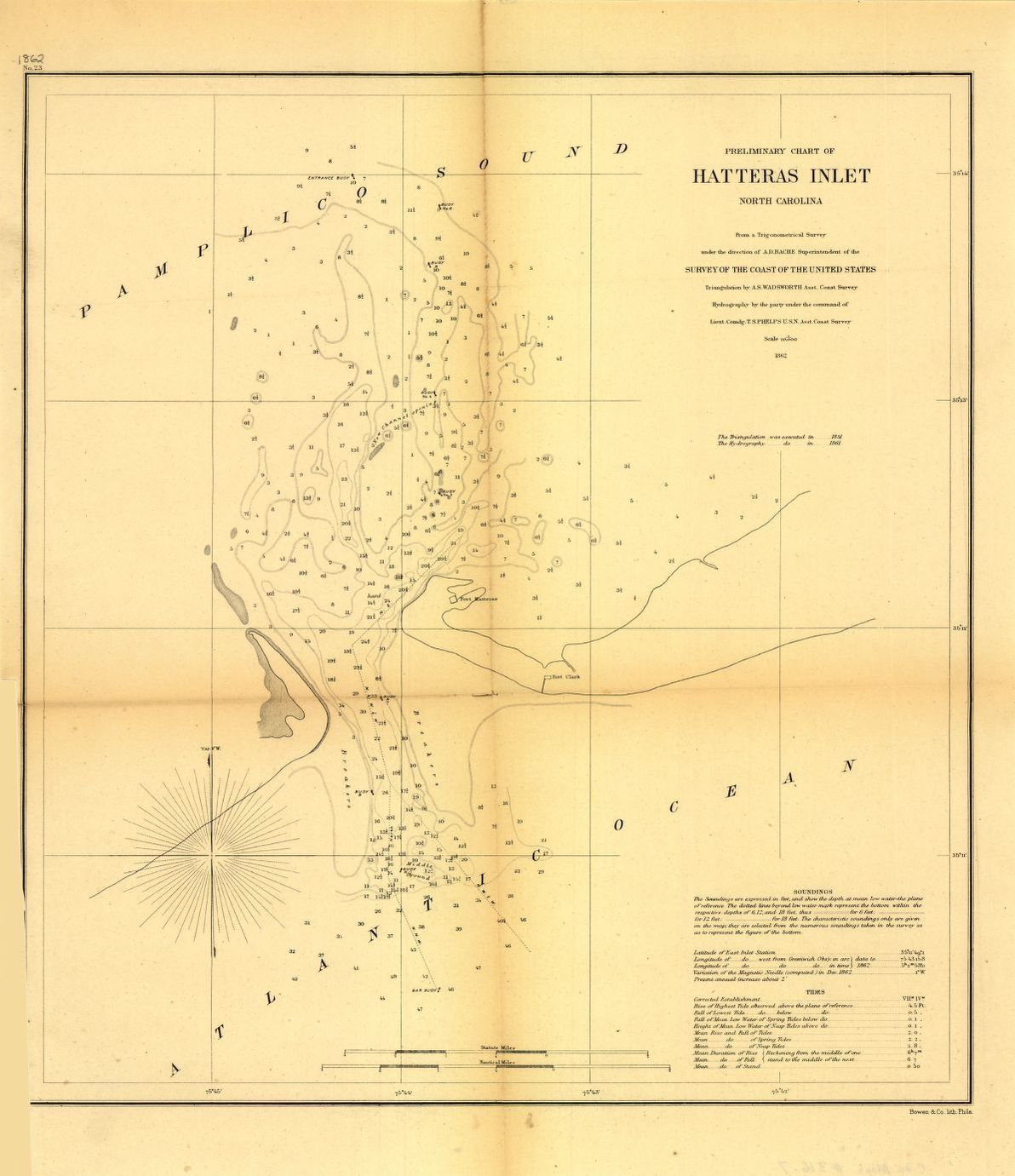

[Washington, U.S. Coast Survey, 1862] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/99447473/.

Hatteras Inlet Forts

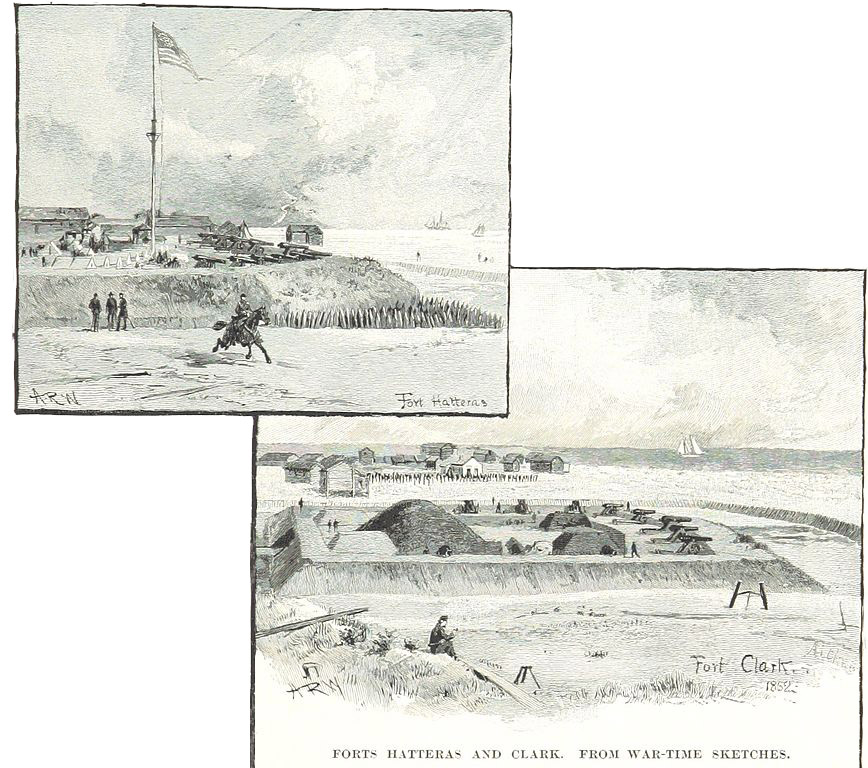

In early summer 1861, the Confederates began the construction of two earthen fortifications to guard Hatteras Inlet. Fort Hatteras was the principal fort, located one-eighth of a mile from the inlet and about three-quarters of a mile from its companion redoubt, Fort Clark. Fort Hatteras commanded the main channel coming through the inlet. It was a square earthwork, approximately 250 feet wide, built of sand. The exterior was covered by wooden planks laid to make a slope. This redoubt was then covered by marsh turf. The fort was armed with a dozen 32-pounders. Another four of these guns had not been mounted. One heavy seacoast gun, a 10-inch rifled gun, had been mounted; however, it did not have any ammunition. Fort Hatteras’s companion fort was sited on the eastern side of the inlet. Named in honor of the governor of North Carolina, Henry Toole Clark, it was much smaller than its counterpart and only mounted five 32-pounders. [4] Both forts were manned by eight companies of the 17th North Carolina Infantry Regiment (previously known as the 7th North Carolina Volunteers). The regiment was organized in June 1861 at Plymouth, North Carolina, and commanded by Colonel William F. Martin. [5] The 17th North Carolina contained companies like the Jonesboro Guards, Tar River Boys, Hamilton Guards, North Carolina Defenders, Lenoir Braves, and Roanoke Guards. [6]

Hatteras Commerce Raiders

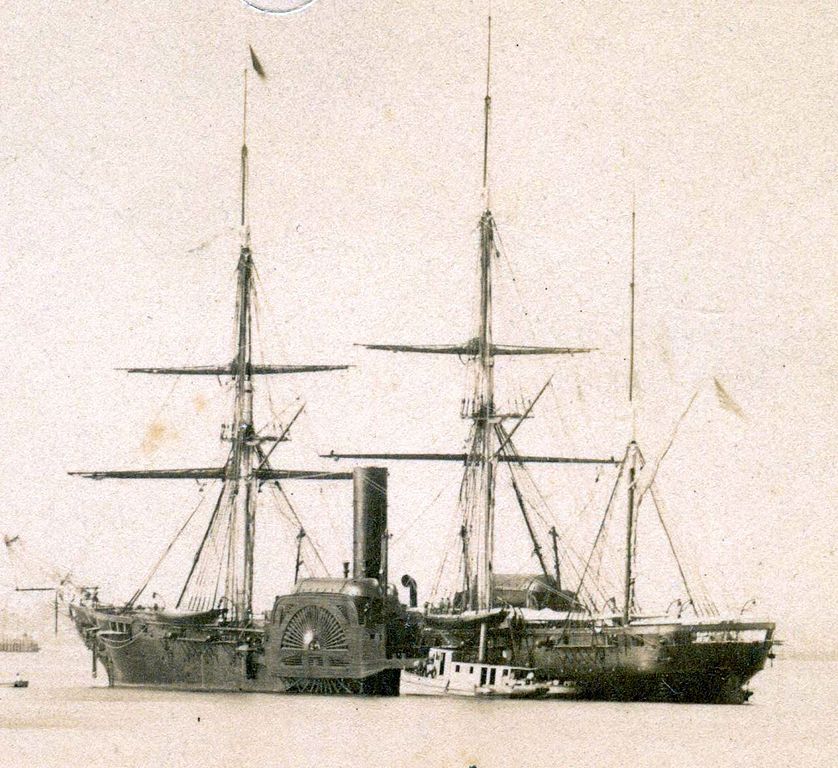

Hatteras Inlet’s unique location was near both Cape Hatteras and the Gulf Stream. This made it a perfect place for Confederate gunboats and privateers to gather and strike out at Northern shipping. Several North Carolina Squadron (Mosquito Fleet) gunboats like CSS Warren Winslow ( often just called Winslow) preyed on Union merchant ships. Lieutenant Commander Thomas M. Crossan commanded Winslow. This steamer enjoyed the most success due to its speed. The sidewheeler was built in 1846 by B. C. Terry of Keyport, New Jersey. The Winslow captured nine vessels, including its richest prize, the brig Lydia Francis, carrying a load of Cuban sugar. Several privateers sought the same easy pickings. The Norfolk pilot boat, the schooner York, captured three merchantmen until it was forced to run aground. A Charleston, South Carolina, privateer, the fast sidewheeler Gordon, took four prizes. [7]

Under Pressure

photographer. Courtesy of National Archives at College Park.

By early August, the Navy Department was bombarded by complaints about the situation along the North Carolina coast by Northern business interests. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles wrote Flag Officer Silas Stringham, commander of the Atlantic Blockading Squadron, that the “accounts we get of intercourse at different ports and inlets on the coast alarm our commercial community and cause embarrassment and distrust to the Department.” Stringham and Welles were well aware of this bad situation. Lieutenant Thomas O. Selfridge Jr., of the sloop of war USS Cumberland, wrote: it “seems that the coast of Carolina is infested with a nest of privateers that have thus far escaped capture, and, in the ingenious method of their cruising, are probably likely to avoid the clutches of our cruisers. Hatteras Inlet, a little south of Cape Hatteras light, seems their principal rendezvous. Here they have a fortification that protects them from assault. A lookout at the light-house proclaims the coast clear and a merchantman in sight; they dash out and are back again in a day with their prize. So long as these remain it will be impossible to prevent their depredations….” [8]

Blockade Strategy Board Speaks

To effectively close Southern ports, the Blockade Strategy Board was established. Led by Captain Samuel Francis DuPont, the Board produced seven reports detailing how to end Southern trade and commerce raiding effectively. It recommended that the first harbor to capture should be Fernandina, Florida; however, they knew that Carolina commerce raiding had to be dealt with first. [9]

Change of Course

The Board recommended that hulk ships be sunk at the entrance to Hatteras Inlet to close it to ship traffic. Commander H.S. Stellwagon was detailed to purchase old hulks in the Chesapeake Bay. When Flag Officer Stringham learned about this proposed action, he immediately wrote Gideon Welles, noting they “speak of the inlet at Hatteras as decidedly the worst place on the coast, and I much regret that I have not two vessels to place and keep there. I have also conversed with these men as to the advantage of sinking vessels in the inlet. They all pronounce it as of little use; because of the light and shifting nature of the sand a new inlet would soon open.[10] Accordingly, it was decided to create a combined operation to capture Hatteras Inlet.

Weakness Discovered

Two of the merchantmen masters captured by the Confederates off Hatteras Inlet wrote a detailed report of Hatteras, Oregon, and Ocracoke inlets’ defenses once they were released. Daniel A. Campbell, master of Lydia Francis, and Henry W. Penny, master of the bark Linwood, had lost their ships. While prisoners, these two men traveled from Hatteras Inlet to New Bern to Raleigh to Ocracoke Inlet until they were allowed in a small boat, with some other Northern seamen, via Oregon Inlet on July 31, 1861. They were eventually picked up by the blockader USS Quaker City. These ship captains made mental notes of Confederate forts guarding the inlets, possible troop landing sites, picket routines, communication problems, mounted cannons, etc. They were very forthright about describing inlet channels, shoals, Confederate gunboats, and privateers. The two captains delivered their report to the New York Board of Underwriters, which had formed a committee to lobby for a Union response to Carolina commerce raiders. [11] This report prompted the Union Anaconda to prepare to squeeze its first victim.

Attack Planning

Gideon Welles approached the War Department about creating a joint operation to capture Hatteras Inlet. The US Navy needed US Army resources to enable a successful operation. Major General John Ellis Wool, a hero of the War of 1812 and the Mexican War, was ordered to provide troops for the expedition. Wool had been advised that the attack on Hatteras Inlet “originated in the Navy Department and is under its control.” [12] When Stringham learned about this stipulation, he knew that his mission’s success or failure had been laid upon his shoulders.

Army Prepares

photographer, Boston. Harper’s Weekly, June 1, 1861.

Wool assigned the mercurial and astute political general Benjamin Franklin Butler to organize a strike force. Butler was famous for his ‘contraband of war decision’; yet, infamous for his command’s defeat during the June 10, 1861 Battle of Big Bethel, in which he started recruiting troops from Camp Butler (Newport News, Virginia) and Camp Hamilton (near Fort Monroe) for the expedition. He successfully secured soldiers from these units:

-220 men from the 9th New York Infantry Regiment (Hawkins Zouaves), commanded by Col. Rush Hawkins;

-500 men from the 20th New York Infantry Regiment (all German immigrants), commanded by Col. Max Weber;

-100 men from the 99th New York Volunteer Infantry (Union Coast Guard), commanded by Captain William Nixon;

-60 men from the 2nd US Artillery Regiment, commanded by Lt. Frank H. Larned.

A total of 880 men were available for the landing on the beach north of Fort Clark. [13] These troops were to be transported to Hatteras Inlet by the steamers Adelaide, captained by Commander Henry S. Stellwagon, and George Peabody, commanded by Lieutenant R.B. Lowry. Neither of these vessels was suited for Atlantic Ocean service; however, they were vessels acquired by Stellwagon to sink, laden with ballast, and block Hatteras Inlet.

Consequently, they were available as troop transports.[14]

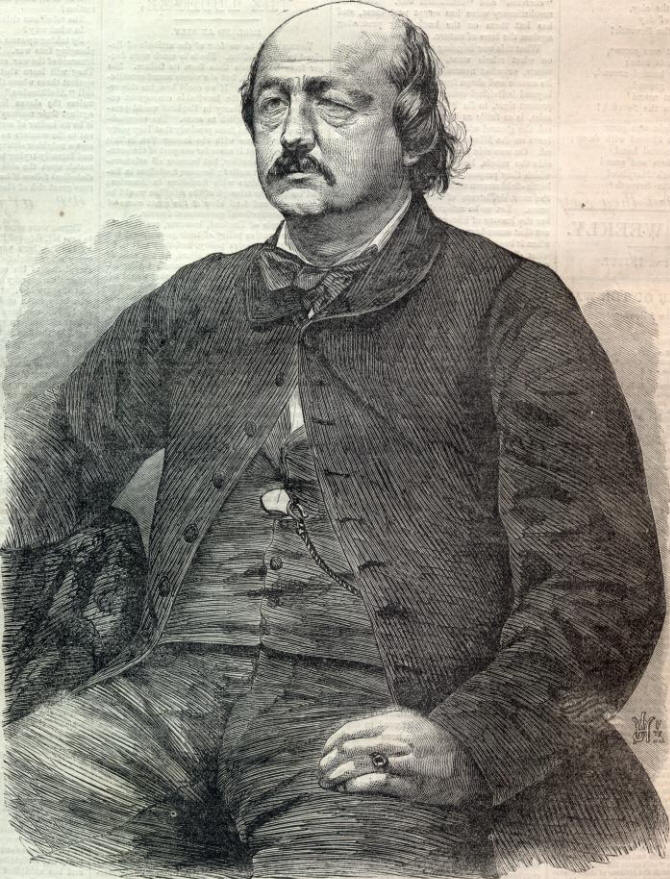

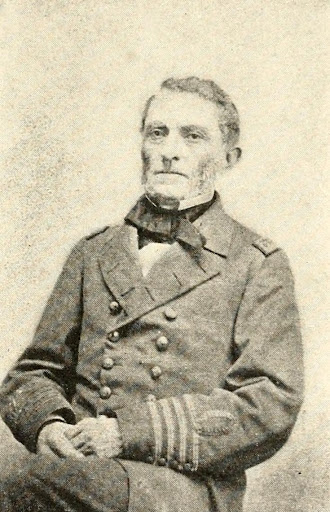

Commander of the Atlantic Blockading Squadron

Flag Officer Silas Horton Stringham was determined to make this amphibious operation a success. He had spent his entire 51-year career in preparation for this event. Stringham joined the US Navy in 1809 at age 11. He served under Captain John Rodgers on the USF President. He participated in the HMS Little Belt Affair (May 1811) and fought during the engagement between President and HMS Belvidera on June 23, 1812. He later engaged in the Second Barbary War under Captain Stephen Decatur. He then spent several years assigned to the Brooklyn and Charlestown Navy Yards and on various warships. Promoted captain in 1841, he commanded the ship of the line USS Ohio during the capture of Vera Cruz in 1847. Before the Civil War, he commanded the Gosport Navy Yard (1851 and 1855-1859) and the Mediterranean Squadron. On May 1, 1861, Stringham was named flag officer, commanding the Atlantic Blockading Squadron. As a senior officer, he had previously participated during the United States’ last amphibious operation during the Mexican War. Now he was in the position to command the Navy’s first amphibious operation of the Civil War. [15]

Hatteras Inlet Naval Expedition Order of Battle

Stringham organized a powerful invasion fleet including:

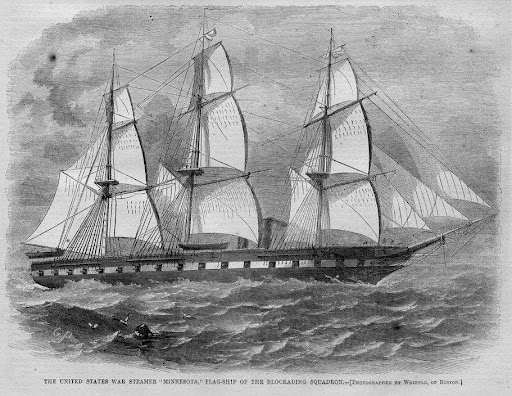

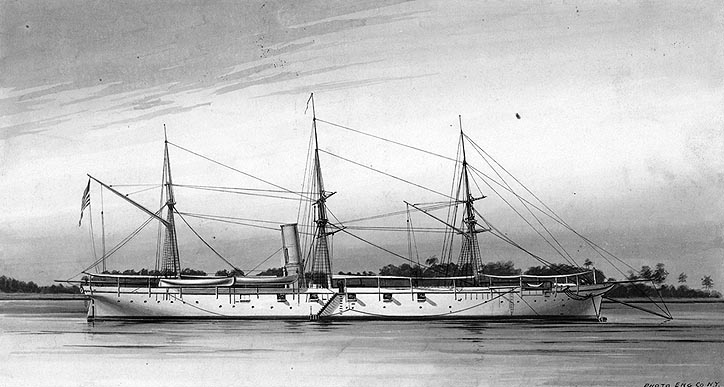

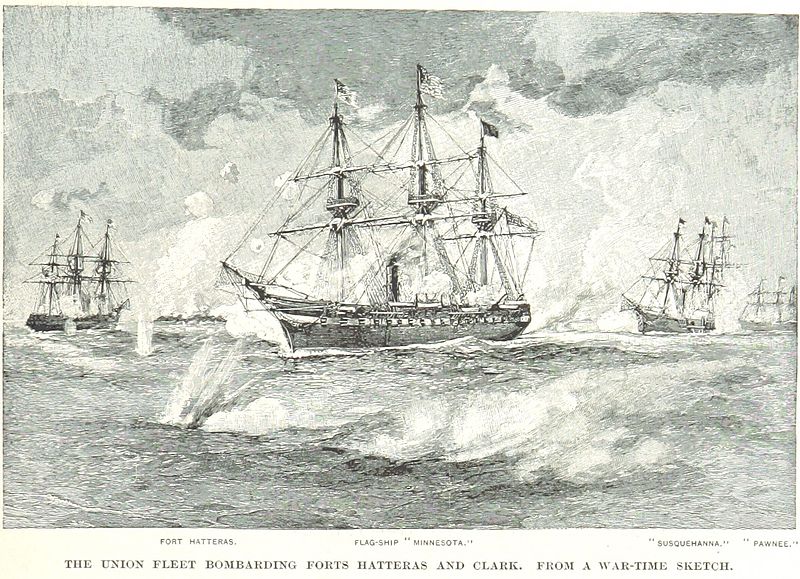

-USS Minnesota, a steam screw frigate mounting one X-inch shell gun, twenty-eight IX-inch shell guns, and fourteen VIII-inch shell guns; commanded by Captain G.J.H. Van Brunt; Flag Officer Stringham’s flagship.

-USS Wabash, steam screw frigate mounting two X-inch shell guns, twenty-eight IX-inch shell guns, fourteen VIII-inch shell guns, and two 12-pounder smoothbores; commanded by Captain Stephen Mercer.

-USRCS Harriet Lane, a sidewheeler commanded by Captain John Faunce, armed with one 4-inch rifled gun, one IX-inch shell gun, two VIII-inch shell guns, and two 24-pounder howitzers.

-USS Monticello, a screw gunboat mounting one X-inch shell gun and two 32-pounders; captained by Commander John P. Gillis.

-USS Pawnee, a screw gunboat mounting four XI-inch shell guns; captained by Commander S.C. Rowan.

-USS Susquehanna, sidewheeler armed with two 150-pound rifles, twelve XI-inch shell guns, and one 12-pounder rifle; commanded by Captain J. Chancey.

-USS Cumberland, sailing sloop of war with an armament of twenty-two IX-inch shell guns, one X-inch shell gun, and one 60-pounder rifle; commanded by Captain John Mason. [16]

Stringham planned to use his heavier ships to bombard the Confederate forts and to use his gunboats to cover the landing. The chartered steamers Adelaide and George Peabody each towed a schooner laden with surf boats. The tug USS Fanny, commanded by Lieutenant Peirce Crosby, came along with the expedition to tow the surf boats ashore.[17]

Destination Hatteras Inlet

Stringham delayed leaving Hampton Roads until August 26, 1861. The flag officer had to wait for good weather due to the poor condition of the transports. The squadron sighted Cape Hatteras Light about 9:30 a.m. on August 27 and moved into position across the bar from the forts. That morning, Colonel Martin was astonished to see all the masts appearing over the horizon in the direction of the inlet. He immediately sent a boat to Portsmouth [Island], North Carolina, to secure reinforcements as he knew he did not have the resources to defend either fort properly. Three hundred sixty-five reinforcements would arrive the next day under the command of Flag Officer Samuel Barron. [18]

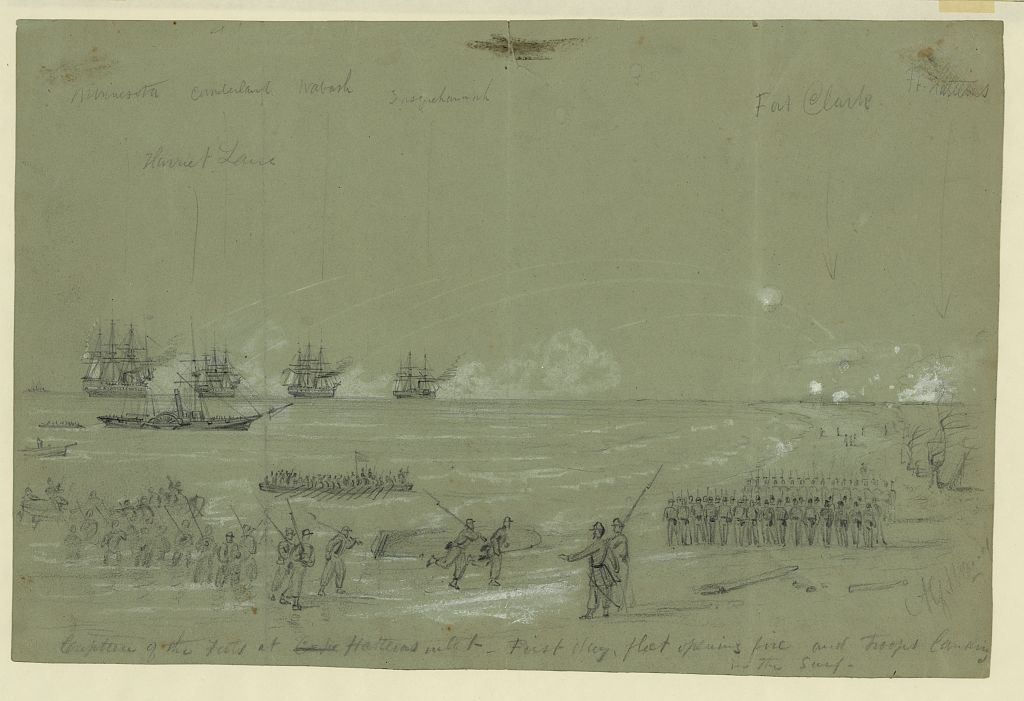

The Landing

When Stringham’s command arrived off Hatteras Inlet, he ordered the surf boats hoisted in preparation for the next morning’s assault. At 4 a.m., the crews were ordered breakfast and then made ready for action. A 12-pounder rifle and a 12-pounder howitzer were lowered into surf boats. Stringham then attached Marines and bluejackets under the command of Captain William L. Shuttleworth to Harriet Lane to support the landing.

Even though there was a strong southerly wind the morning of August 28, which created heavy surf, Stringham signaled to “disbark troops at 6:45 a.m.” The flag officer then detailed Harriet Lane, Monticello, and Pawnee to move toward shore to cover and assist in landing the troops on the beach, two miles north of Fort Clark. [19]

Weather conditions worsened as the morning progressed. Only 320 men landed before General Butler stopped the operation. Colonel Max Weber assumed command of these men, including 100 from his regiment, 68 soldiers from the 9th New York, 28 from the Union Coast Guard, 45 artillerymen, 45 Marines, and 28 sailors. The heavy surf caused the metal surf boats to sink and break up the wooden ones. Somehow they managed to pull the two cannon ashore; however, Weber’s command was stranded. The only water was in their canteens, they had no food or ammunition, and they were soaked to the skin. Luckily, no one drowned. [20]

The Union troops appeared isolated and in trouble. The gunboats observed what appeared to be Confederate cavalry rushing toward the stranded soldiers. Federal ships rapidly opened fire on the ‘raiders,’ however, they turned out to be a herd of wild Hatteras ponies, spooked by the artillery shells landing near Fort Clark. [21]

Stringham’s New Tactics

The heavy ships, Minnesota and Wabash towing Cumberland, got underway at 8:45 a.m. and opened fire on Fort Clark. By 11 a.m., Susquehanna joined the battle line. Stringham took a tactic used by French and British warships at the siege of Sevastopol, and one new to American naval strategy. He kept his ships moving in a circle so they would not be fixed targets for the forts. The Union warships would be the first to fire their broadsides and would reload as they looped back to fire again. None of the Union ships were damaged.

Fort Clark Falls

While Fort Clark was being pounded by the Federals’ ships, the garrison struggled to defend itself. The fort’s 32-pounders did not have the range or accuracy to strike any Union vessels. By 12:25 p.m., the Confederates had run out of ammunition and abandoned Fort Clark. The heavy ships kept firing even though the North Carolinians had lowered Fort Clark’s flag and could be seen escaping from the redoubt. Stringham kept up fire until Col. Weber’s troops made it into the Confederate fort and raised a US flag. One Union soldier was wounded in the hand by a shell fragment. [22]

USS Susquehanna, USS Pawnee bombard Fort Hatteras. From Battles and Leaders

of the Civil War, 1887. Courtesy of Mechanical Curator Collection, British Library.

Mistaken Opportunity

As the bombardment smoke cleared, it was noted that not one Confederate flag was flying from Fort Hatteras. Stringham believed that both forts had been abandoned, so he sent Monticello and Harriet Lane into the inlet. The Harriet Lane grounded inbound; however, Monticello steamed into the channel. Once within range of the fort, it was struck by five shells, “blowing away the steamer’s boat davits, riddling the galley pantry and armory with shell fragments.” [23] The Monticello was not badly damaged despite a gash across its deck. It safely retreated away from Hatteras Inlet. Stringham, shocked by the shellfire from Fort Hatteras, ordered to engage batteries. The Union began to bombard the remaining fort mercilessly until the weather worsened and darkness shrouded Fort Hatteras’s profile.

Alfred Waud, artist, August 28, 1861. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Barron to the Rescue?

Flag Officer Samuel Barron arrived with reinforcements from Fort Ocracoke aboard the gunboat CSS Warren Winslow. Several sailors stayed to help operate the guns. The garrison now reached more than 700 men, and more reinforcements were expected from New Bern. Barron, commander-in-chief of the coastal defense for upper North Carolina and lower Virginia, was asked by Colonel Martin to assume command of Fort Hatteras. The flag officer agreed and then concocted a plan to recapture Fort Clark with a bayonet charge. Little did Barron know that Col. Max Weber’s men were demoralized and isolated in the fort. Nevertheless, when the expected reinforcements did not arrive from New Bern, Barron canceled this assault and decided to focus on strengthening Fort Hatteras. [24]

Bombardment Begins Anew

At 5:30 a.m. on August 29, 1861, Stringham made the general signal, “Prepare to engage batteries and follow my motions.” Stringham had ordered Monticello and Pawnee to attend to the troops ashore. The two gunboats were advised to either re-embark or resupply Weber’s command with food. At 7:30 a.m., he gave another general signal, “Attack batteries, but be careful not to fire near the battery in our possession.” Eventually, Stringham would stop his ships circling movement and anchor them to improve their aim. [25] By 11 a.m., a white flag was raised above Fort Hatteras. Hatteras Inlet was now captured. This meant the beginning of the end for Outer Banks commerce raiders.

Fort Hatteras Surrenders

The fort’s garrison withstood a relentless barrage of shells. “It was like a hailstorm,” one member of the garrison recounted. Another noted the “firing of shells became…literally tremendous as we had falling into and immediately around the work not less on average of ten shells each minute, and the sea being smooth, the firing was remarkably accurate.” [26] It is estimated that more than 3,000 shot and shells were sent into Fort Hatteras that morning.

Barron faced an impossible situation. Not only were the fort’s guns outranged by those of the Federal fleet, but the Confederates were low on ammunition. There was no way for the garrison to escape, and they knew they would not be reinforced. Truly a hopeless situation, so Barron raised the white flag.

Taking Credit

When Ben Butler saw the white flag over Fort Hatteras, he boarded the tug Fanny and rushed to the fort to accept Barron’s unconditional surrender. It was an amazing yet, extremely low cost and lucky victory. The Federals lost one killed and two wounded, whereas the Confederates lost four killed and 20 wounded along with 601 captured.

As soon as the surrender ceremony was completed, Butler dashed back toward the Chesapeake Bay to make a report about his “great” victory. Butler’s command had little to do with the Union victory as it was Stringham’s Atlantic Blockading Squadron’s bombardment of the Confederates’ Hatteras Inlet forts that made the expedition a resounding success. Meanwhile, Stringham collected all prisoners to deliver them to their POW camp at Fort Columbus on Governors Island, New York.

Political Aftermath

As Butler worked to receive the credit for the victory at Hatteras Inlet, Stringham was initially treated like a conquering hero! The North needed a victory after the terrible defeats at Big Bethel and First Manassas (Bull Run) to boost the nation’s morale. The victory at Hatteras Inlet certainly helped. Very quickly, however, the press and public turned against Stringham. Many criticized his actions. The Navy Department did not believe that the flag officer had effectively maintained the blockade of the Southern coast. Furthermore, Stringham was heavily criticized for not following up on the Hatteras Inlet victory. Lieutenant John Pyne Bankhead wrote the Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Vasa Fox: “after the fight they had a foot race North to see who should get there first and get the most credit. Butler beat Strigham Stringham — had they both remained, we might have had the whole coast in our possession.” [27]

Stringham recognized he was losing favor in the Navy Department and was perturbed by Butler’s ascension to glory. Accordingly, he resigned on September 16, 1861. His resignation may have come later anyway as his command would soon be split into the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron and South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Stringham’s ego would not have survived this ‘demotion.’

‘The Vandals Are On Our Coast — Our Soil is Invaded’

The Confederates did not realize the damage that had been wrought to their cause with the loss of Hatteras, North Carolina. The Confederates abandoned Ocracoke and Oregon inlet forts. This move made it simple for the Federals to control much of the Outer Banks and allowed easy access into the Sounds. These actions would set the stage for General Ambrose Burnside’s Roanoke Island Expedition. The Confederate government never recognized the importance of North Carolina’s Sounds to their war effort and never effectively supported the defense of North Carolina. This was an unwise decision. While the loss of this rich agricultural region would harm the Confederate supply system, the capture of Hatteras Inlet gave the Union a position from which they could capture Norfolk or cut the all important railway line from the Deep South to Richmond. Admiral David Dixon Porter later noted: “This was our first naval victory, indeed our first victory of any kind, and should not be forgotten. The Union cause was in a depressed condition, owing to the reverses it had experienced. The moral effect of this affair was great, as it gave us a foothold on Southern soil and possession of the Sounds of North Carolina if we chose to occupy them. It was a death-blow to blockade running in that vicinity and ultimately proved to be one of the most important events of the war.” [28]

Endnotes

1. Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, (Hereinafter referred to as ORN), ser. 1, vol. 6, pp.77-78.

2. William R. Trotter, Ironclads and Columbiads, Winston-Salem, North Carolina: John F. Blair Publisher, 1989, p. 16.

3. John V. Quarstein and J. Michael Moore, Yorktown’s Civil War Siege, History Press: Charleston, South Carolina, 2012, p. 23.

4. Robert Holmes, Encyclopedia Of Historic Forts, New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1988, pp. 612 and 617.

5. Walter Clark, ed., Histories Of The Several Regiments And Battalions From North Carolina In The Great War 1861-1865, Raleigh, NC: E.M. Uzzell, Printers and Binder, 1901, vol. 2, p. 75.

6. ORN, ser. 1, vol. 6, pp. 128-129.

7. Trotter, pp. 22-23, and Paul H. Silverstone, Civil War Navies 1855-1883, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2001, pp. 180-181,185 & 193-194.

8. ORN, ser. 1, vol. 6, pp. 71-72.

9. IBID., p. 72, and ORN, ser. 1, vol. 12, pp. 195-198.

10. IBID., p. 64

11. IBID., pp. 77-80.

12. IBID., p. 109.

13. IBID., p. 112

14. IBID., p. 120.

15. Patricia Faust, ed., Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia Of The Civil War, New York: Harper Perennial, 1986, p.727.

16. Silverstone, pp. 14,16, 25, 80,97,139.

17. ORN, ser. 1, vol. 6, p. 120.

18. Trotter, p.34.

19. ORN, ser. 1, vol. 6, p. 321.

20. War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, ser. 1, vol. 4, pp. 592-594.

21. Trotter, p. 35.

22. ORN, ser. 1, vol, 6, p.121.

23. IBID., p. 123.

24. Robert M. Browning Jr., From Cape Charles to Cape Fear: The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron During the Civil War, Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 1993, pp. 13-14.

25. ORN, ser. 1, vol. 6, p.121.

26. Trotter, p. 37.

27. Browning, p. 15.

28. Naval History Division, Navy Department, Civil War Naval Chronology 1861-1865, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, p. 1971.

Read more about Coastal NC in the Civil War in these blogs by John Quarstein: Burnside’s Roanoke Island Expedition and From New Bern to Beaufort.