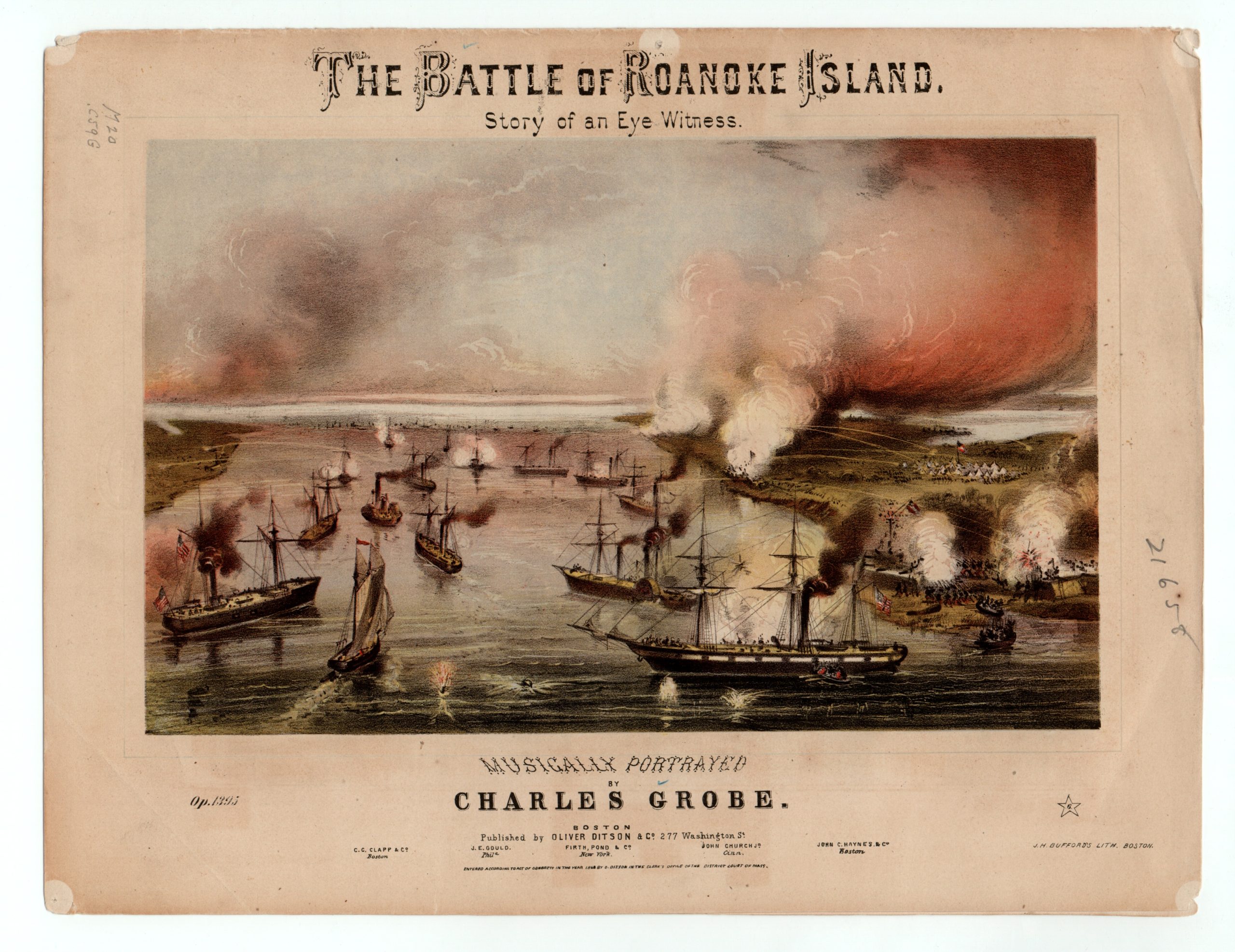

Major General George B. McClellan recognized the need for combined operations to overwhelm the Confederate war effort. With more than 3,000 miles of coastline to defend, the Southerners were often unable to protect their coastal territory effectively. The captures of Hatteras Inlet and Port Royal Sound were decisive actions that furthered General Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan. Brigadier General Ambrose Burnside’s Roanoke Island Expedition would strike at the very heart of the Confederacy. This effort to conquer North Carolina’s inland seas would come close to ending the war in 1862.

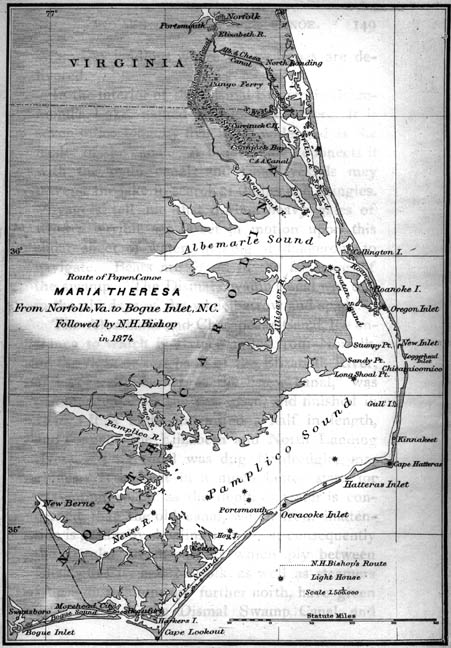

Voyage of the Paper Canoe by Nathaniel H. Bishop, https://www.ibiblio.org/eldritch/nhb/paperc/intro.html#maps.

The Great Inland Sea

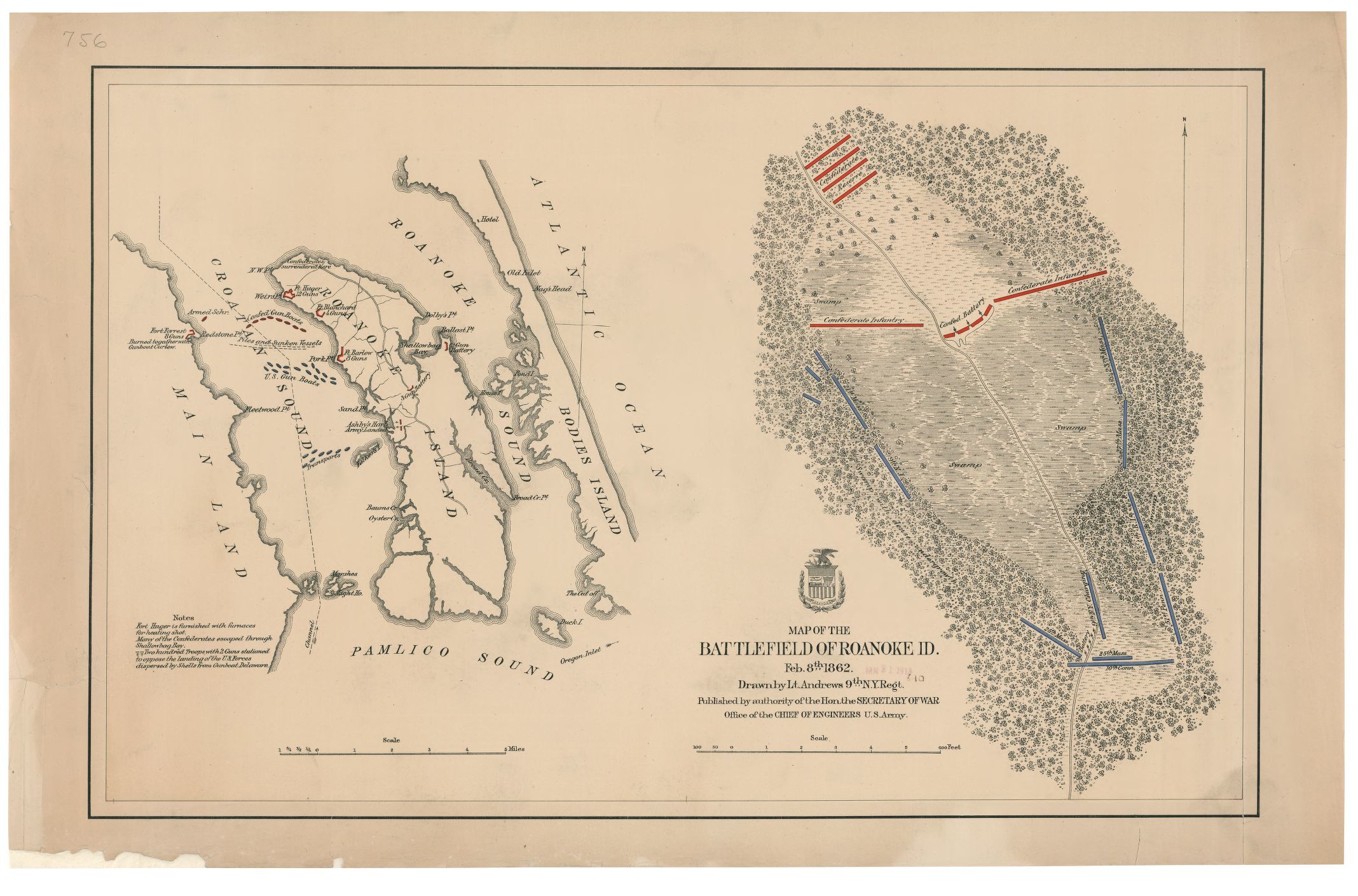

The loss of Hatteras Inlet was a rude awakening for North Carolina. The Federals suddenly had complete access to the sounds, and the key to the control of the various shallow bodies of water was Roanoke Island, located at the confluence of the Albemarle and Currituck Sounds. These large sounds led to Norfolk and Portsmouth, Virginia, via the Great Dismal Swamp and the Albemarle & Chesapeake Canals. This was the backdoor to the South’s largest shipbuilding center and was a direct link to Richmond. These sounds gave access to critical North Carolina river ports such as Elizabeth City, Edenton, and Plymouth.

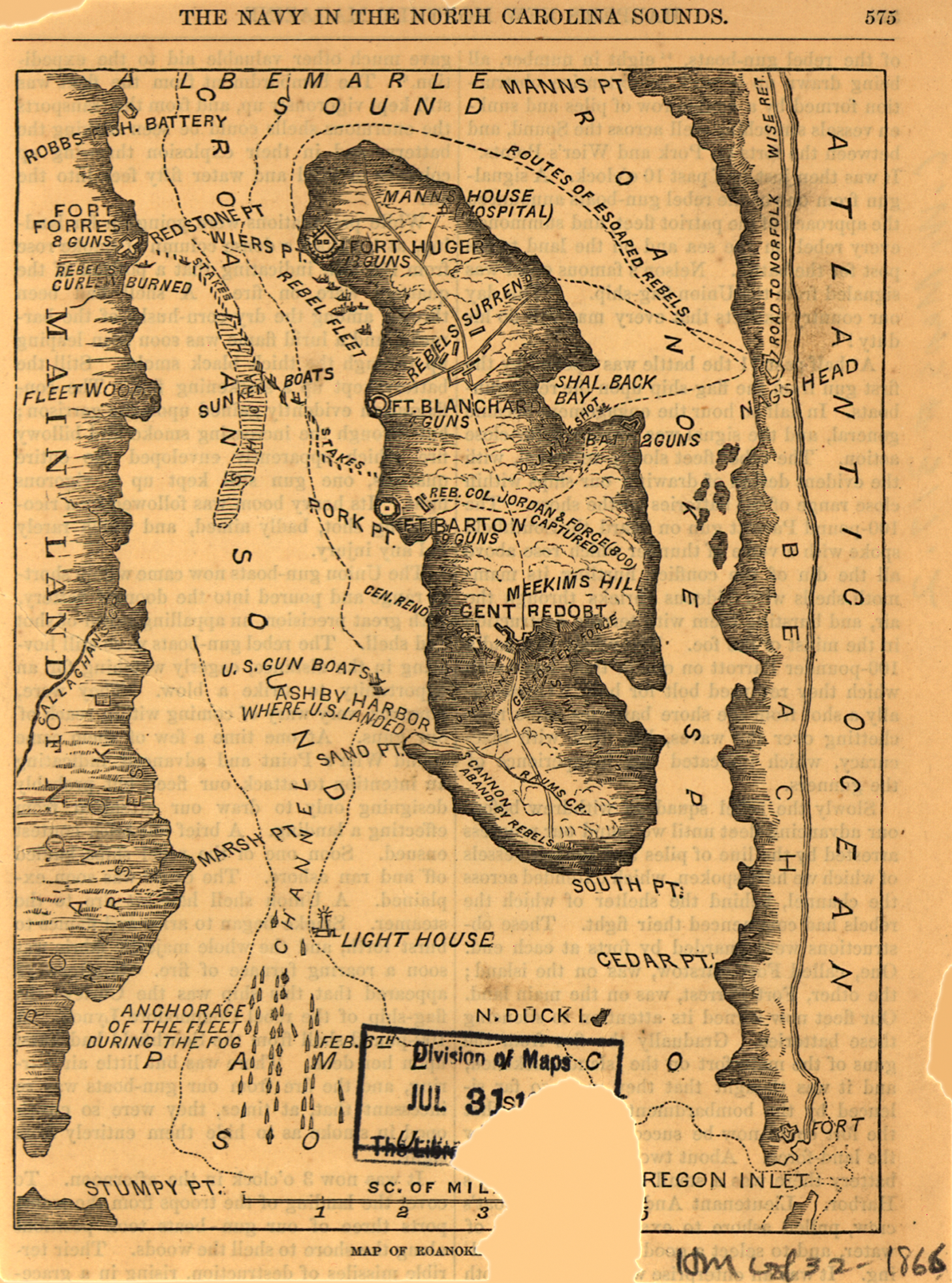

Roanoke Island was bounded to the west by Croatan Sound and the east by Roanoke Sound. Croatan was deeper and led directly to Pamlico Sound, the largest sound that provided access to such major cities as New Bern and Beaufort. The various rivers that fed the sounds reached inland toward railroads, which supplied the main battlefront in Virginia with food and other materiel coming from Wilmington, North Carolina, and the Deep South. Without these connections, the war would be quickly over for the South.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, G3902.R6S5 1862 .A5.

Carolina Defenseless

North Carolina’s governor, Henry T. Clark, pleaded with Confederate president Jefferson Davis to provide more military support for coastal Carolina defense. The Davis administration thought it best to focus and believed that sending military resources to North Carolina would weaken the Confederacy’s opportunity to win a decisive victory in Virginia. After the Union capture of Hatteras Inlet, Governor Clark was especially concerned about Roanoke Island’s defense.

Clark wrote the Confederate Secretary of War Judah Benjamin stating: “Besides the arms sent to Virginia in the hands of our volunteers, we have sent to Virginia 13,500 stands of arms, and we are now out of arms, and our soil invaded, and you refuse our request to send us back some of our own armed regiments to defend us….we have disarmed ourselves to arm you…the recent invasion compels us again to buy a navy for our protection, not receiving it from the Confederate States. We are denied powder, on the ground that we have received more than any other state, without advertising that the powder has been made into cartridges and sent back to Virginia with every regiment….”[1]

New Commanders

Richmond refused to effectively respond to Governor Clark’s needs other than assign two new generals to resolve Eastern North Carolina’s defense. Brigadier General Richard Caswell Gatlin was assigned on July 8, 1861, as the Department of North Carolina commander. Gatlin, an 1832 USMA graduate, fought in the Mexican War and was a member of Albert Sidney Johnston’s Utah Expedition. Heavily criticized for the loss of Hatteras Inlet in late August 1861, Gatlin moved his headquarters to Goldsboro, North Carolina, and reorganized his district into two commands.[2]

Brigadier General Joseph Reid Anderson was given command of the Cape Fear District with a brigade of troops. Anderson, an 1836 West Point graduate, was the owner of Tredegar Iron Co.[3] In turn, Brigadier General D. H. Hill was assigned control of the Pamlico and Albemarle Sounds’ defenses. Hill, who graduated from West Point in 1842, was a veteran of the Mexican War and had served as the superintendent of the North Carolina Military Institute when North Carolina left the Union. He commanded the Ist North Carolina Regiment during the Confederate’s first victory at Big Bethel, Virginia, and was promoted brigadier general. Abrasive and outspoken to his fellow officers, Hill was recklessly brave and well-loved by soldiers under his command. [4]

Inadequate Support

General Hill assumed his new command in October 1861. He went on a 15-day inspection tour and submitted a report detailing the poor conditions found throughout Eastern North Carolina. “Fort Macon has but four guns of long range, and these are badly supplied with ammunition….New Bern has a tolerable battery, two 8-inch Columbiads and two 32-pounders. It is; however, badly supplied with powder….Roanoke Island is the key to one-third of North Carolina, and whose occupation by the enemy would enable him to reach the great railroad from Richmond to New Orleans. Four additional regiments are absolutely indispensable to the protection of this island. The batteries also need four rifled cannons….the towns of Elizabeth City, Edenton, Plymouth, and Williamston will all be taken should Roanoke be captured or passed.”[5]

Change in Command

Hill then set to work building earthworks to defend the island, which was 12 miles long and three wide at its widest point. Hill began to prepare an earthwork across the island’s center to block any possible Union advance. Unfortunately, he was transferred back to Virginia, and his district was divided in two. The Confederacy placed the southern part (Pamlico, Core, and Bogue Sounds) under Brigadier General Lawrence O’Bryan Branch’s command. Branch reported to General Gatlin.

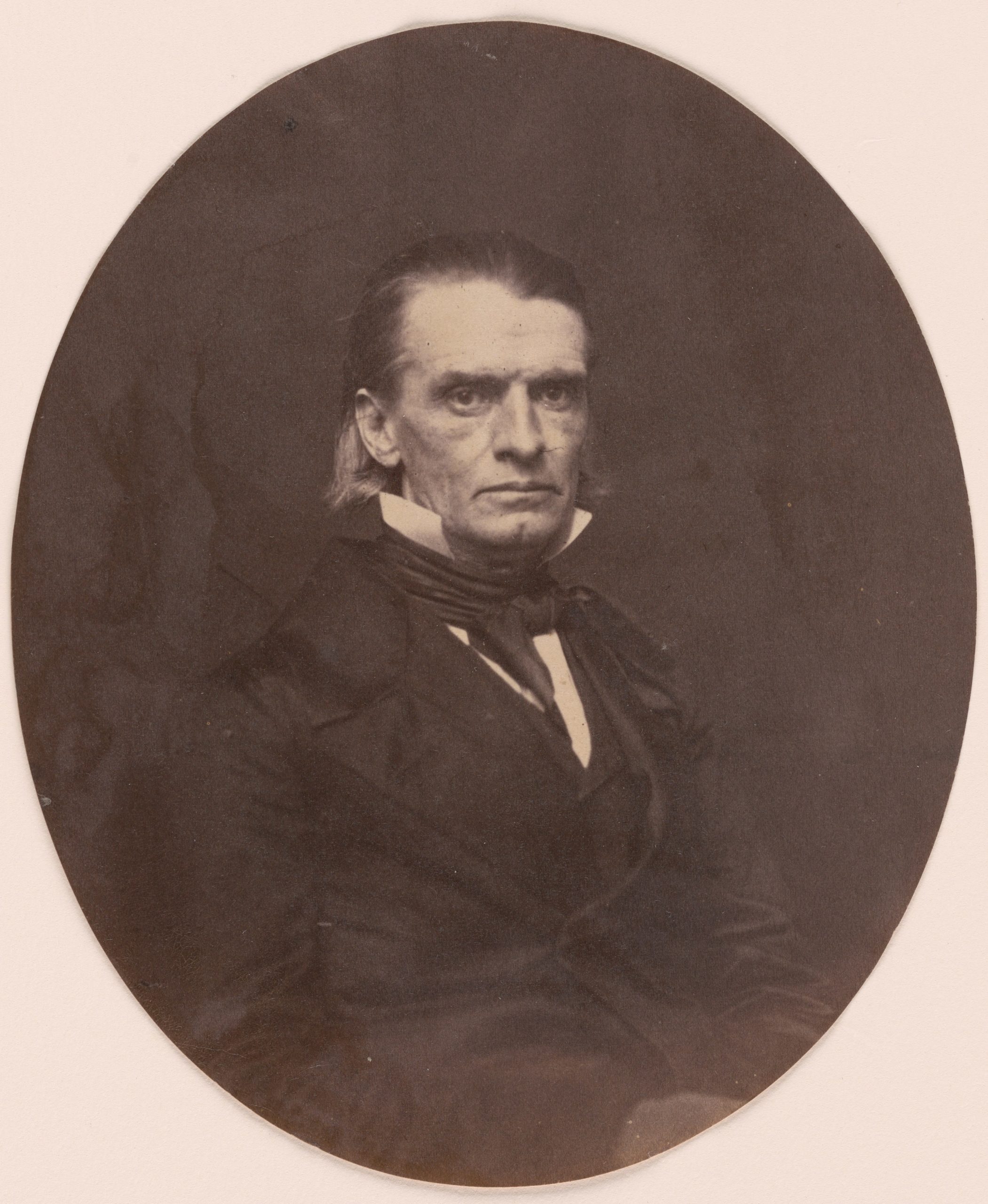

The northern section covered Croatan, Albemarle, and Currituck Sounds. This region included Roanoke Island as well as the canals and railroads reaching Virginia. A strategic area, this was placed under the command of Brigadier General Henry Alexander Wise. Unfortunately, Wise’s command was placed within the Norfolk Department commanded by Major General Benjamin Huger.

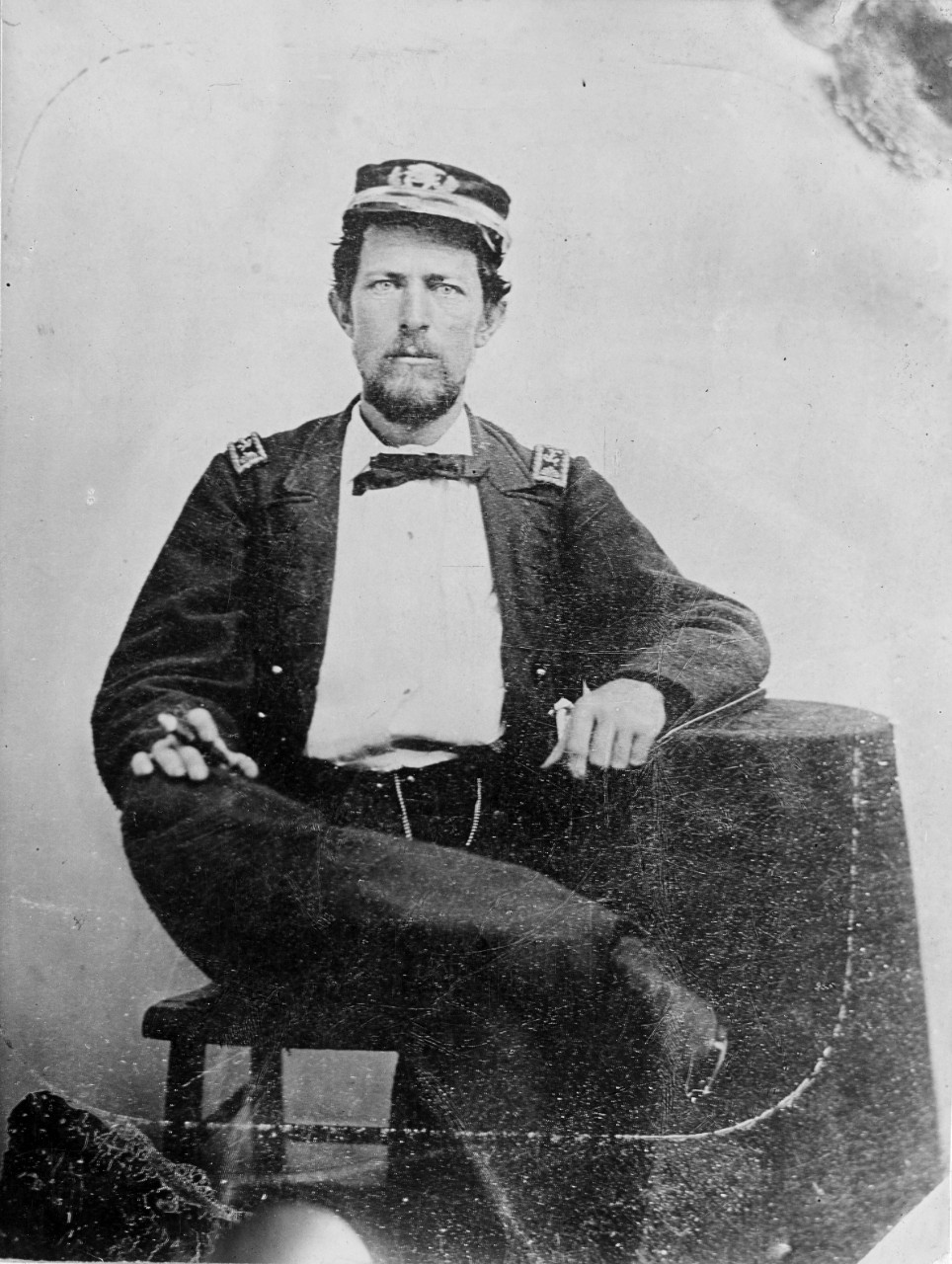

Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Henry Alexander Wise, from Virginia’s Eastern Shore, was an excellent orator and dynamic politician. He attended Washington College in Pennsylvania, and then became a successful lawyer. Wise was elected to the US House of Representatives in 1832. He served as a Congressman until 1843, when he was appointed minister to Brazil, serving until 1847. Elected governor of Virginia in 1856, the final act of Wise’s term was the execution of abolitionist John Brown. A strong advocate of Virginia’s secession. Wise joined the Confederate army as a brigadier general on June 5, 1861, despite having no prior military service. Following a failed campaign in West Virginia, he was assigned to command the North Carolina Sounds’ Northern District.[6]

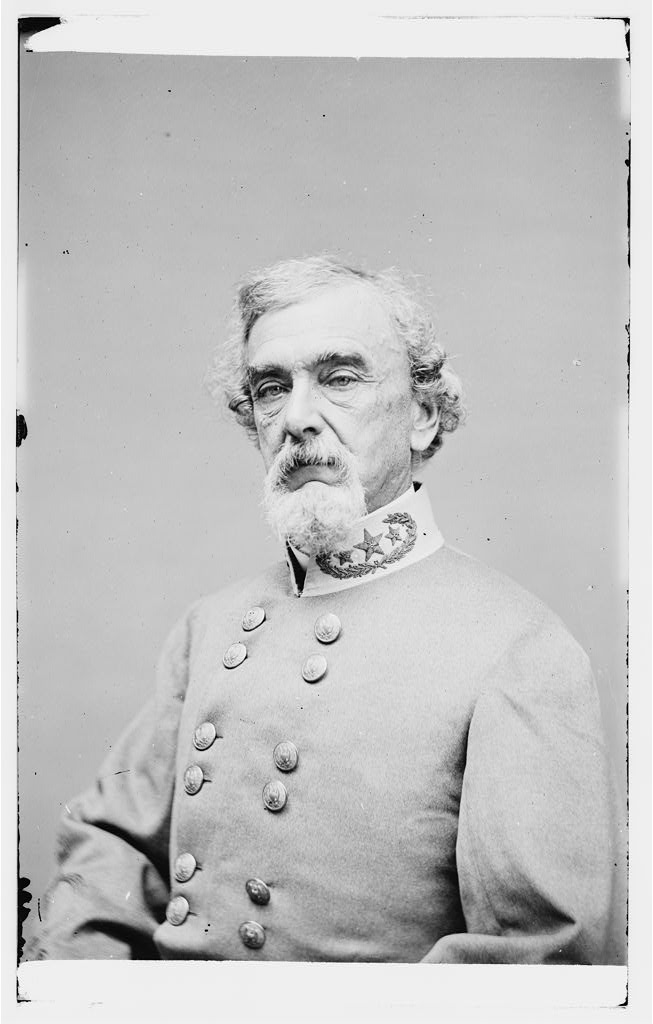

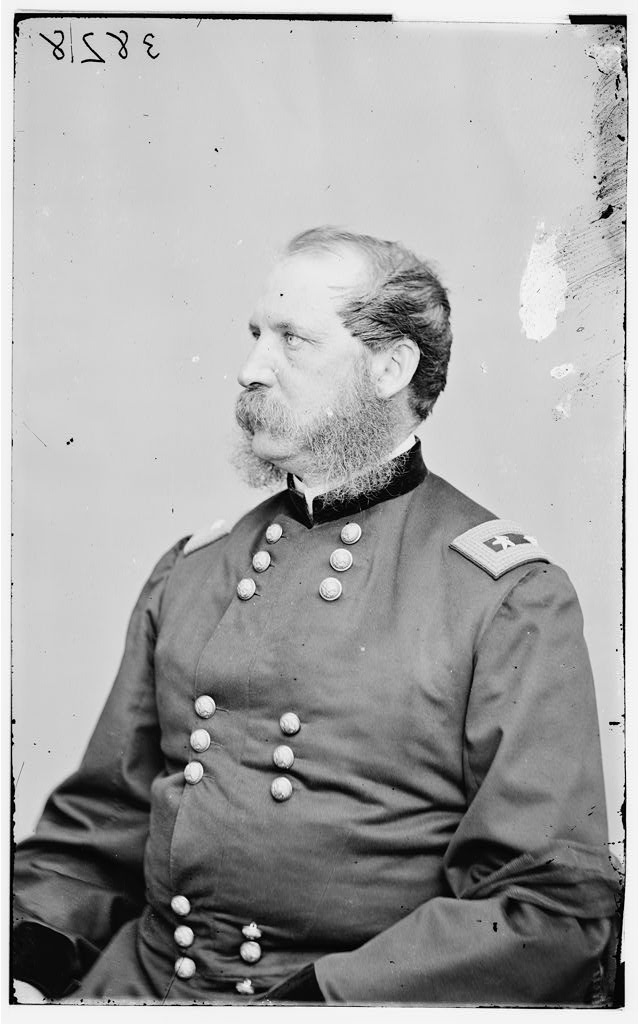

Wise reported to Major General Benjamin Huger, whose headquarters was in Norfolk, Virginia. Huger, an 1825 graduate of USMA, was eventually assigned to the Ordnance Department. He assumed command of various armories, such as at Fort Monroe, Virginia. During the Mexican War, Huger served as chief of ordnance for General Winfield Scott’s army that captured Mexico City. He was brevet colonel and spent the 1850s managing armories in the Upper South. South Carolina presented him a dress sword “in recognition of the honor his career had cast upon his native state.”[7] Huger joined the Confederate army as a brigadier general on June 17, 1861, and was soon promoted to major general.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-B813- 1978 A [P&P] LOT 4213.

Norfolk Must Be Protected

Huger focused on building forts, like Sewell’s Point Battery, to defend the river approaches to Norfolk and Gosport Navy Yard. He failed to appreciate the critically strategic importance of Roanoke Island. Norfolk was directly connected to the Currituck and Albemarle Sounds via two significant canals: the Dismal Swamp and Albemarle & Chesapeake Canals. General Wise continued to request troops and cannons for the defense of Roanoke Island. It was evident to most military commanders that Roanoke Island was a key to Norfolk’s defense; yet, Huger did not seem to grasp this concept.

Forts are Built

Secretary of the Navy Stephen Russell Mallory sent 242 cannons from Gosport Navy Yard to North Carolina. Many of these found their way to Roanoke Island.[8] Wise continued to build the fortifications started by Hill. The island’s defense began north of Port Ashby, with earthworks crossing the center of the island. This fortification blocked the one road running the island’s length. This redoubt was eighty feet long and set at right angles to the road and armed with one 24-pounder, one 18-pounder, and one six-pounder. Impassable cypress swamps and bogs supposedly secured the fort’s flanks. One Roanoke Island native firmly stated: “When one of the cows gets in there, we leave her there, for we know we can’t get her out.”[9] Several other forts were constructed to guard the Croatan Sound coastline.

Fort Bartow was sited on Pork Point and armed with nine 32-pounders. The artillery was commanded by Lt. Benjamin Loyall, CSN. Two additional earthworks were constructed overlooking Croatan Sound. Fort Blanchard was armed with four 32-pounders. Fort Huger, at Weir’s Point, mounted ten 32-pounders and ten 32-pounder rifles. Across Croatan Sound, on Redstone Point, was Fort Forrest. This position was two old canal boats pushed up onto the mudflats. Cotton bales and sandbags protected the fort’s seven 32-pounders. Wise had placed piles and old wrecks sunk by CSS Appomattox to act as a barrier from the east side of Fulker’s Shoals. Also, on the east side of the island, a two-gun battery was positioned on Ballast Point. [10]

More Troops Needed

Wise believed that he needed 5,000 men to defend the island. Instead, he only had just over 1,400 soldiers. The former Virginia governor pleaded with General Huger, who had 15,000 soldiers assigned to the defense of Norfolk, for additional troops. Huger just could not grasp the concept that Roanoke Island was the key to the canals that reached Norfolk, and he refused to support Wise. By the end of January 1862, Roanoke Island’s defenses were manned by troops from Virginia and North Carolina.

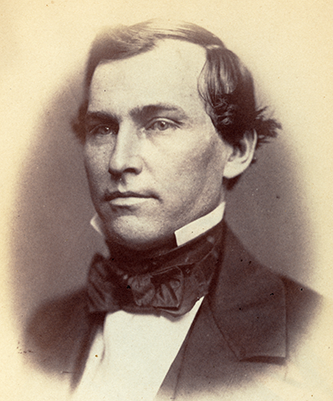

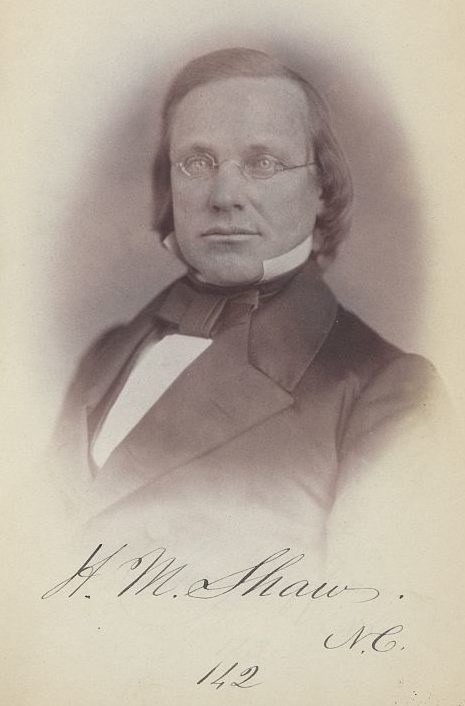

The 46th and 59th Virginia regiments were originally part of Wise’s Legion. They were well-armed and equipped. The North Carolina units were recently formed and rushed to the island to aid in its defense. Colonel Henry M. Shaw was a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. He moved to Indiantown (now Shawboro), North Carolina, to establish a practice. He was elected to the House of Representatives in 1852 and again in 1856. An advocate of North Carolina’s secession, he organized the 8th North Carolina Regiment and was detailed to Roanoke Island. Shaw became second in command of the island’s defenses and controlled elements of the 2nd and 17th North Carolina regiments. These units were newly organized and poorly trained. Many were armed with shotguns, fowling pieces, and small-game rifles. The artillery crews were “infantrymen the week before and did not know a ramrod from a lanyard.” [11]

It was noted after the island’s capture that the “prisoners were mostly set, all clothed (I can hardly say uniformed) in dirty looking homespun gray cloth. I should think every man’s suit was cut from a design of his own… and no two men dressed alike. Their head covering was in unison with the rest of their rig from stovepipe hats to coonskin caps…”.[12]

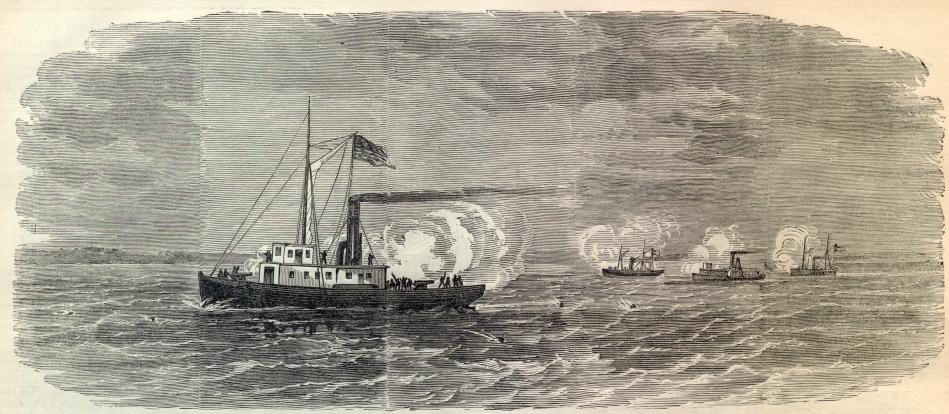

The Mosquito Fleet

In addition to these limited land defensive resources, Flag Officer William Lynch had organized the 9-vessel North Carolina Squadron. Known as the ‘Mosquito Fleet,’ it consisted of converted tugs and transports/passenger vessels. Lynch joined the US Navy in 1819 and is most noted for exploring the Jordan River and the Dead Sea. In 1849 he published his findings, Narrative Of The United States To The Jordan River And Dead Sea. Lynch proved that the Dead Sea was below sea level. He also wrote Naval Life; Or, Observations Afloat And On Shore. A true gentleman in every sense and a devout Episcopalian, he resigned his commission and joined the CS Navy. He first commanded Confederate batteries at Aquia Creek, Virginia, and then was assigned to lead the North Carolina Squadron. An outstanding combat leader, Lynch’s administrative skills were lacking, and he was called by CSS Albemarle’s builder Gilbert Elliot as being “incompetent, inefficient and also an imbecile.” [13]

General Wise thought that “Captain Lynch was energetic, zealous, and active, but he gave too much consequence entirely to his fleet of gunboats, which hindered transportation of piles, lumber, forager, supplies of all kinds, and of troops, by taking away the steam-tugs and converting them into perfectly imbecile gunboats.” [14]

The squadron’s flagship was CSS Sea Bird, a sidewheeler built by Benjamin Terry at Keyport, New Jersey, in 1854, and commanded by Lieutenant Patrick McCarrick. Just 133 feet long, Sea Bird mounted one 32-pounder shell gun and one 30-pounder rifle.

The other North Carolina Squadron warships included:

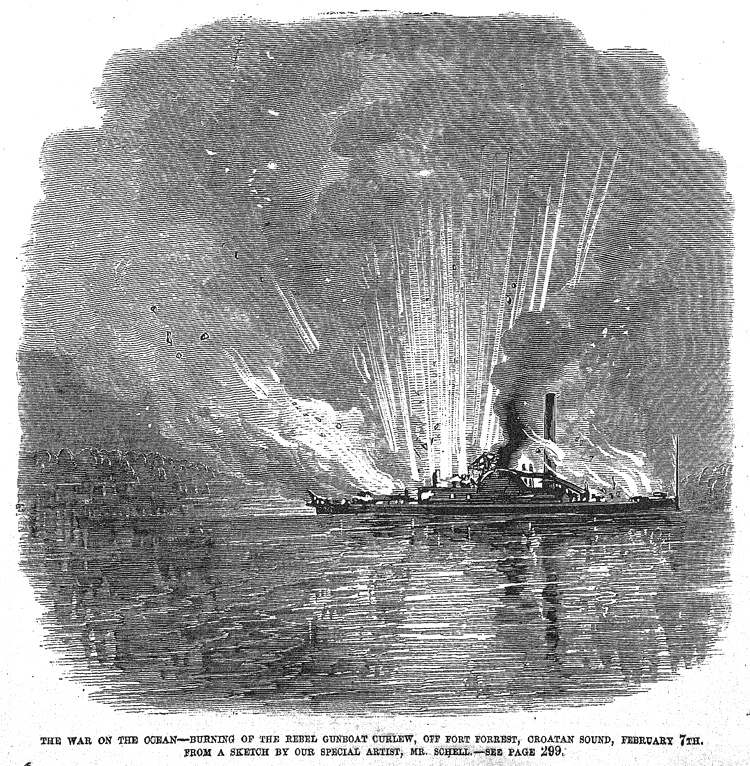

–CSS Curlew: an iron-hulled gunboat built by Harlan & Hollingsworth Iron Shipbuilding Company of Wilmington, Delaware, in 1856. The 135-foot-long steamer, commanded by Lt. Thomas T. ‘Tornado’ Hunter, was armed with one 32-pounder and one 12-pounder howitzer.

–CSS Ellis: an iron-hulled screw steamer built in Wilmington, Delaware. This shallow draft gunboat was armed with one 32-pounder rifle and one 12-pounder howitzer.

–CSS Beaufort: Built in Wilmington, Delaware, and first named Caledonia, this 85-foot-long screw steamer mounted one 32-pounder rifle and was commanded by Lt. William Harwar Parker.

–CSS Raleigh: Originally an iron-hulled screw tugboat working the Albemarle Sound, this steamer commanded by Lt. Joseph W. Alexander, was armed with two 6-pounders.

–CSS Forrest: Previously named J.A. Smith and Weldon N. Edwards, CSS Forrest was a worn-out steam screw tug armed with one 32-pounder and one 12-pounder howitzer.

–CSS Appomattox: Constructed in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1850. An 86-foot-long steam screw tug commanded by Lieutenant Charles Carroll Simms, the gunboat was armed with one 32-pounder and one 12-pounder howitzer. It was used to tow blockships to sink hulks in the Croatan Sound.

–CSS Black Warrior: A two-masted 92-foot-long schooner built at Plymouth, North Carolina, it was armed with two 32-pounders.

This small squadron did have one victorious action. On October 1, 1861, Curlew, Raleigh, and Junaluska surprised and captured the USS Fanny in Loggerhead Inlet. The Fanny was added to the Mosquito Fleet and was armed with a 4.62-inch Sawyer rifle and one 8-pounder rifle. Junaluska did not remain with the squadron[15]

Harper’s Weekly, Oct. 19, 1861.

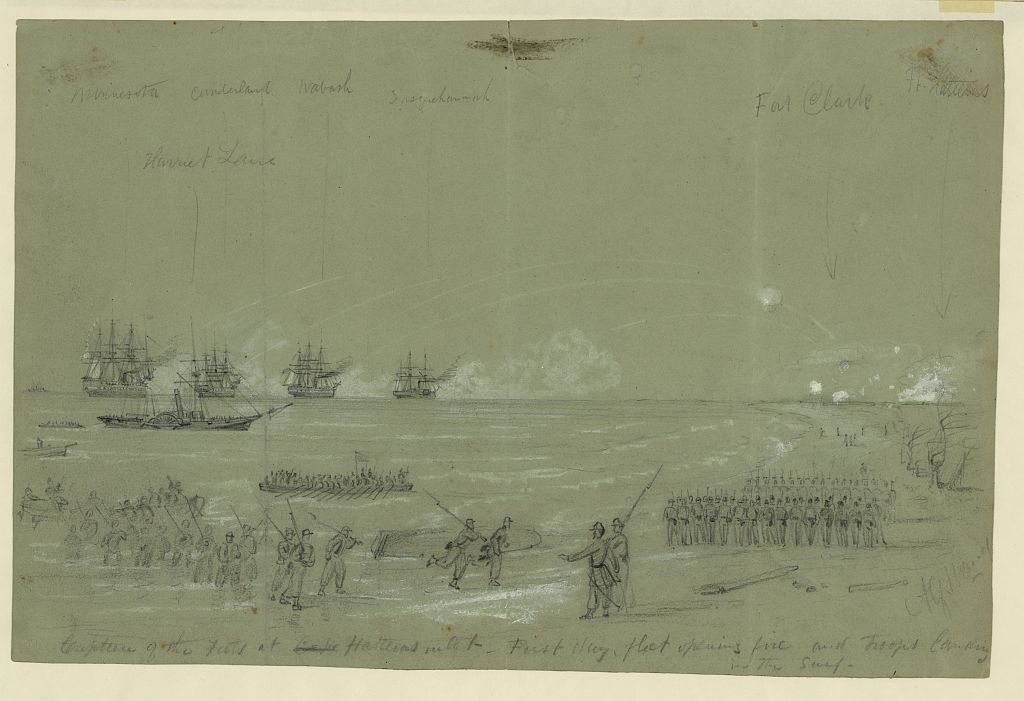

North Atlantic Blockading Squadron

As the Confederates struggled with developing the defense of the sounds, the Federals made plans to invade the inland sea. The joint operation by Flag Officer Silas Horton Stringham and Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler that had captured Hatteras Inlet gave the Union the deepest entrance into the sounds. Confederate gunboats and privateers continued to harass Northern shipping off the Outer Banks. This squadron’s purpose was to maintain the blockade from Cape Charles, Virginia, to Cape Fear, North Carolina. The newly minted commander of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron was Flag Officer Louis Malesherbes Goldsborough.

Goldsborough’s first order of business was to close Oregon, Loggerhead, and Ocracoke Inlets with sunken hulks. Commander Henry S. Stellwagen was initially given the task; however, he failed to sink any old vessels in any channel because of harassment by Confederate gunboats, a lack of knowledgeable pilots, and bad weather. Lieutenant Commander Reed Werden replaced Stellwagen with Goldsborough’s admonition that “what the Department wishes is to have its orders executed, if possible, and nothing more.” [16] Even though he believed the project was without merit, Werden temporarily blocked Ocracoke Inlet with three hulks by November 14, 1861.

‘Old Guts’

Flag Officer Goldsborough was a difficult man to please and was not well-loved by the officers and men serving under him. Born in 1805, he was warranted a midshipman at the age of seven. Goldsborough did not see active duty until he was eleven years old. He led a steamboat expedition during the 2nd Seminole War and commanded the ship of the line USS Ohio during the Mexican War. During the 1850s, Goldsborough served as superintendent of the US Naval Academy and as commander of the Brazil Squadron. [17]

While considered a capable officer by many of his peers and the Navy Department, numerous officers who served beneath him did not appreciate his talents or command style. Acting Assistant Paymaster William Keeler of USS Monitor believed that “the commodore is not the man for the position he occupies–real merit never placed him there. He is coarse, rough, vulgar & profane, fawning & obsequious to his superiors–supercilious, tyrannical & brutal to his inferiors.” The paymaster also advised his wife: “He hasn’t the first qualification of an officer or a gentleman & I don’t know if any officer under him respects him in the least. He is monstrous in size, a huge mass of inert animal matter & is known throughout his whole fleet by the very significant appellation of ‘Old Guts.’” [18]

The Blockade

The Blockade Strategy Board believed that combined operations with the Army could provide the US Navy with bases up and down the Confederate coast. The capture of Forts Clark and Hatteras guarding Hatteras Inlet gave the Federals a toehold entrance into the North Carolina sounds. As the Federal fleet endeavored to block other inlets, Brigadier General Ambrose Burnside had already approached Major General George Brinton McClellan about his concept to organize a ‘coastal division’ to operate within the Chesapeake region. Burnside thought recruiting fishermen, sailors, and watermen from New England’s seacoast towns would result in troops well-trained for amphibious operations.

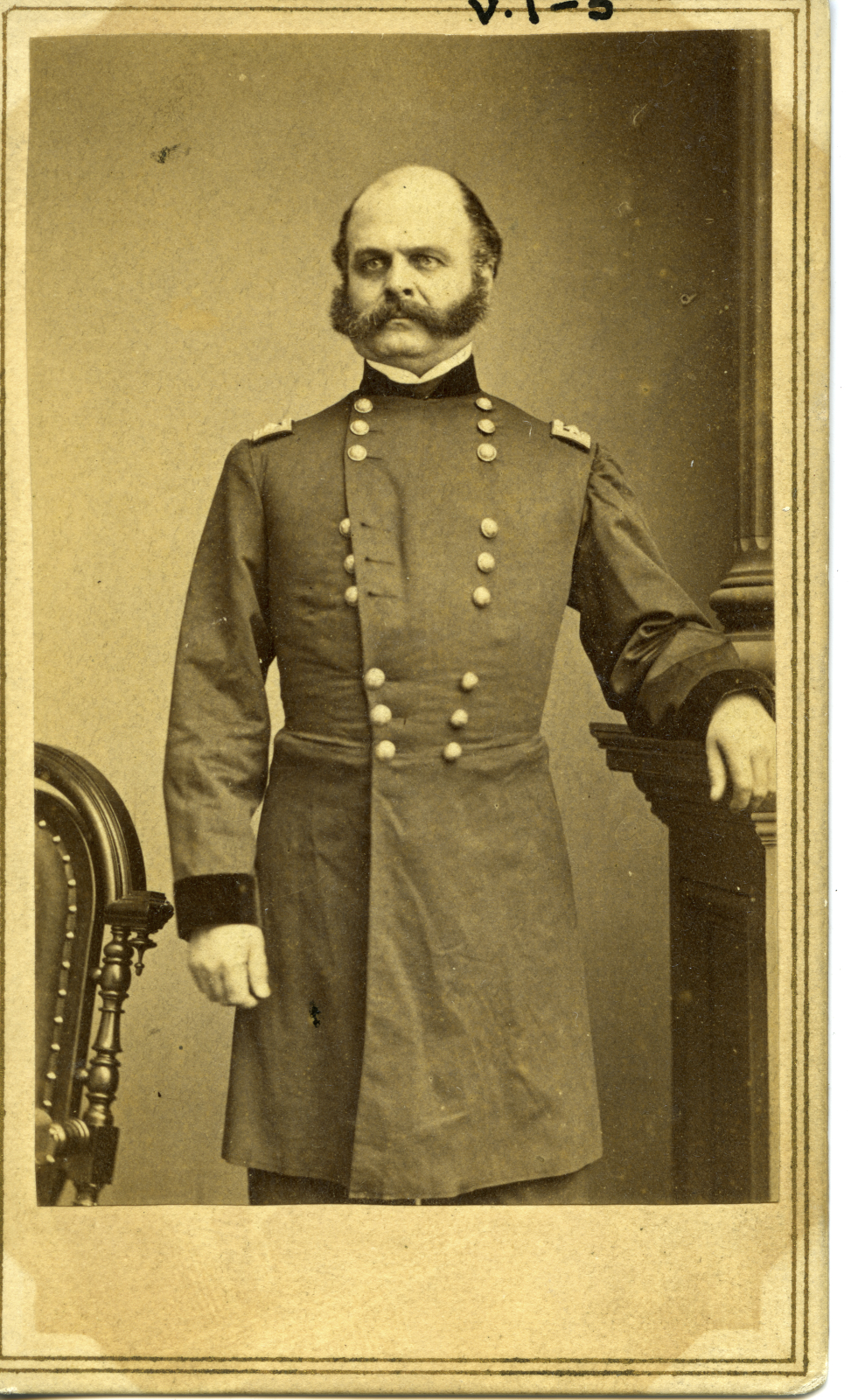

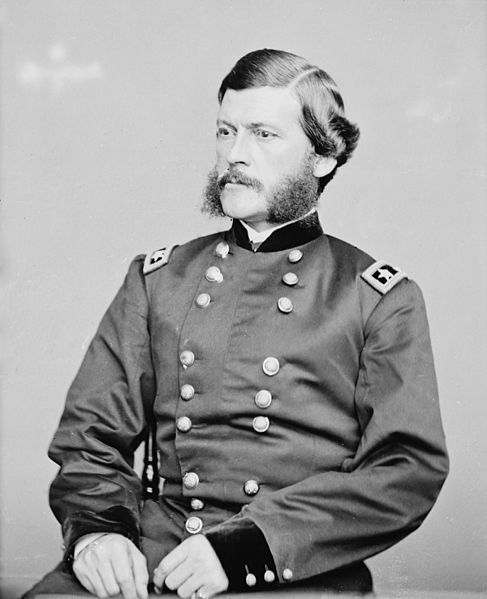

Ambrose Everett Burnside: The Man Who Made Sideburns Stylish

Burnside was an 1847 graduate of USMA and served in garrison duty and on the southwest frontier. He resigned his commission in 1853 to go into the arms manufacturing business as he had invented a breech-loading carbine. Sadly, his Bristol Firearms Co. of Rhode Island failed to secure any government contracts. Burnside went bankrupt. Fortunately, his close friend, George McClellan, was chief engineer of the Illinois Central Railroad and gave him a job as treasurer. When war threatened, Burnside organized the 1st Rhode Island Volunteers in April 1861 and, as a colonel, commanded a brigade during the First Battle of Bull Run. [19] Promoted to brigadier general, he began to recruit troops for his Coastal Division in October 1861.

Coastal Division

Promoted to brigadier general, Burnside immediately began recruiting troops for his Coastal Division in October 1861. He was able to create an amphibious division of about 12,000 men. The division’s commander picked three of his good friends from West Point to be his brigade commanders. Brigadier General John Gray Foster, USMA 1846, had fought in the Mexican War and was severely wounded at the battle of Molino del Ray. Foster had been chief engineer for the Charleston, South Carolina, coastal defenses during the siege and capture of Ft. Sumter in April 1861. Foster commanded the First Brigade.

Brigadier General Jesse Lee Reno commanded the Second Brigade. Reno was an 1846 graduate of USMA and fought with “gallant and meritorious conduct” during the battles leading to Mexico City’s capture. Before the war, he was an instructor at West Point and commanded arsenals at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

Brigadier General John Grubb Parke first attended the University of Pennsylvania and then graduated from USMA in 1849. Before the Civil War, he served as an engineer in Minnesota, New Mexico Territory, California, and Washington Territory. [20]

Union Order of Battle

First Brigade

10th Connecticut

23rd Massachusetts

25th Massachusetts

27th Massachusetts

Second Brigade

21st Massachusetts

51st Pennsylvania

9th New Jersey

51st New York

6th New Hampshire

Third Brigade

53rd New York

89th New York

8th Connecticut

11th Connecticut

4th Rhode Island

5th Rhode Island Battalion

9th New York, Hawkins Zouaves, from Newport News Point, Virginia,

was added to this brigade.

Artillery

Battery F. 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery

1st New York Marine Artillery

Burnside’s Navy

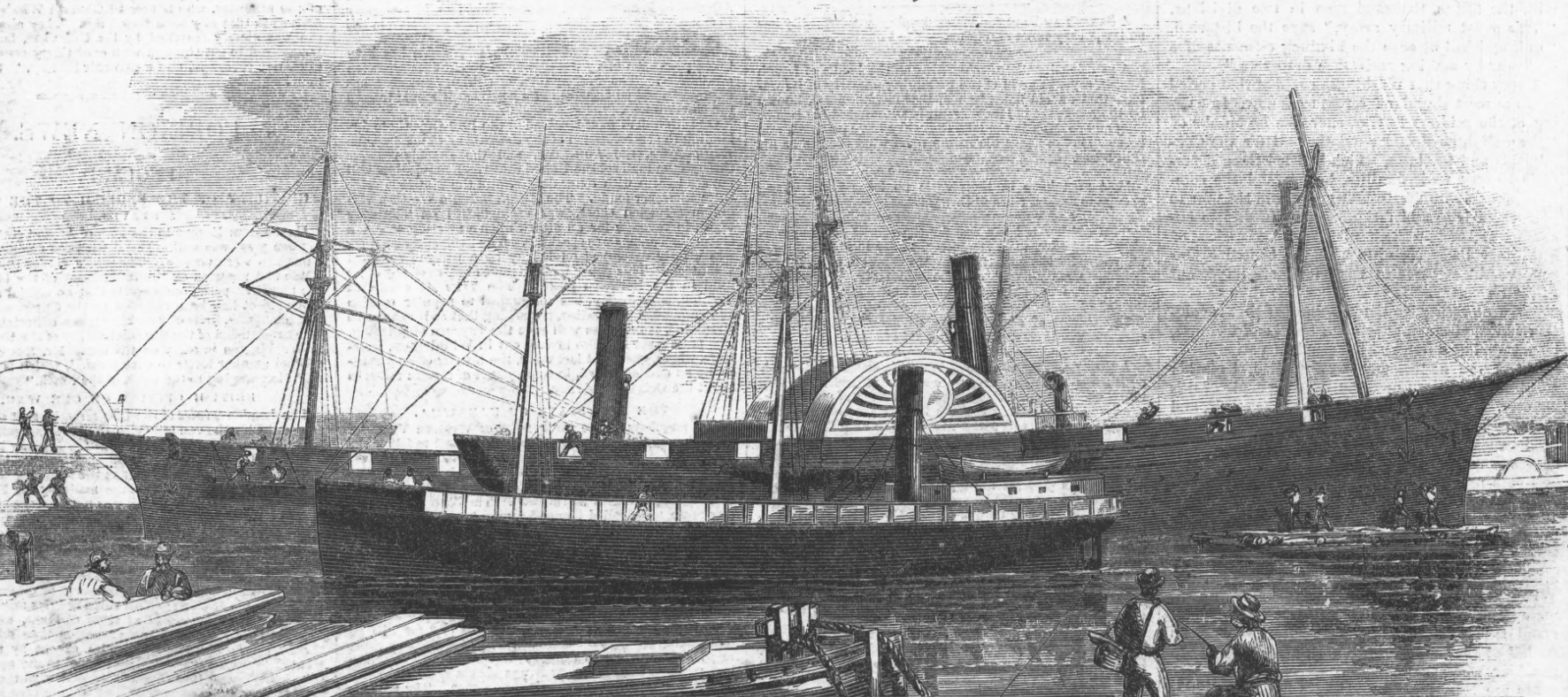

General Burnside also needed to obtain ships with drafts that could pass through the shallow Hatteras Inlet. The general purchased old ferry boats, transports, tugs, and garbage scows. Most of these ships had too great a draft or were otherwise ill-suited for the task at hand. He also purchased some gunboats to provide close-in support, which Goldsborough called a ”paste-board fleet,” as the Army maintained control of its ships just as the Navy did theirs. He suggested to Assistant Secretary of the Navy G. V. Fox that “in case of another joint expedition, everything concerning all vessels should be arranged exclusively by the Navy, & kept under Naval control. DUALITY, I assure you, will not answer.” Goldsborough’s message: If it walks, it belongs to the Army; if it floats, it belongs to the Navy. [21]

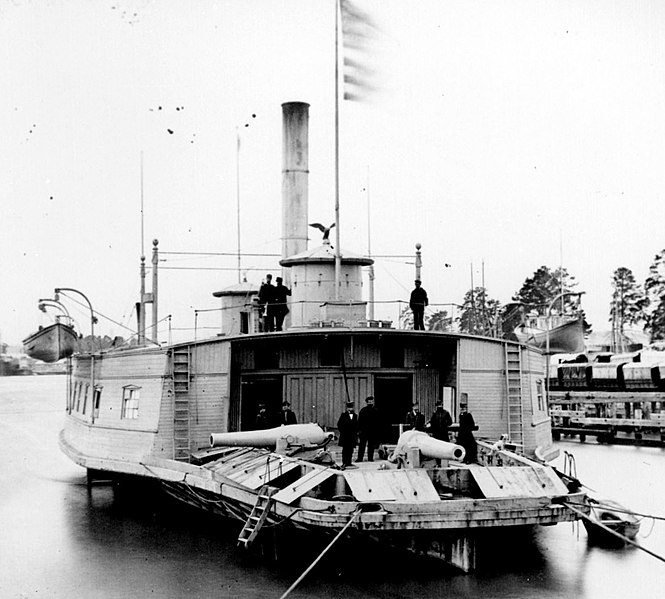

US Navy Gunboats

Goldsborough focused on bringing nearly 20 shallow-draft gunboats to support Burnside’s Expedition. The naval force featured:

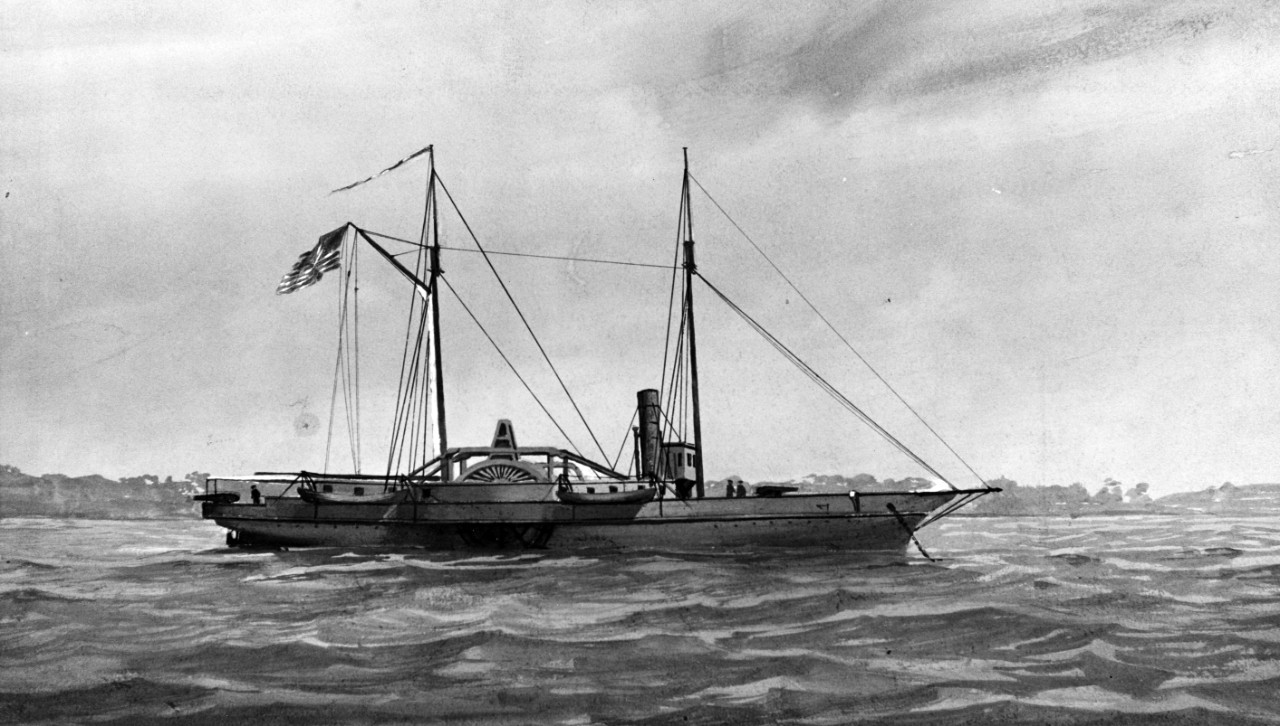

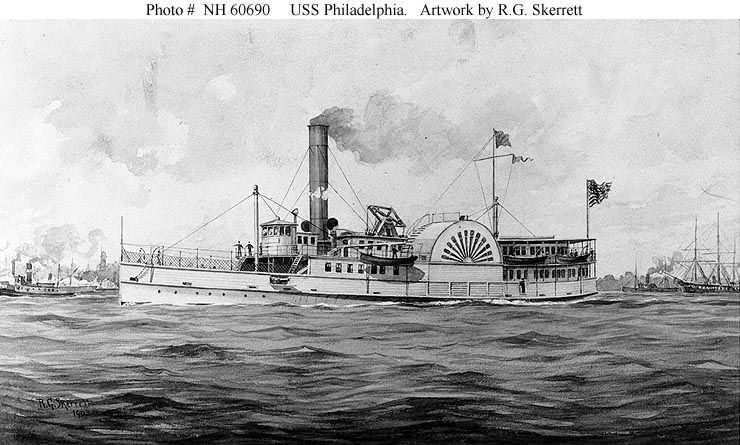

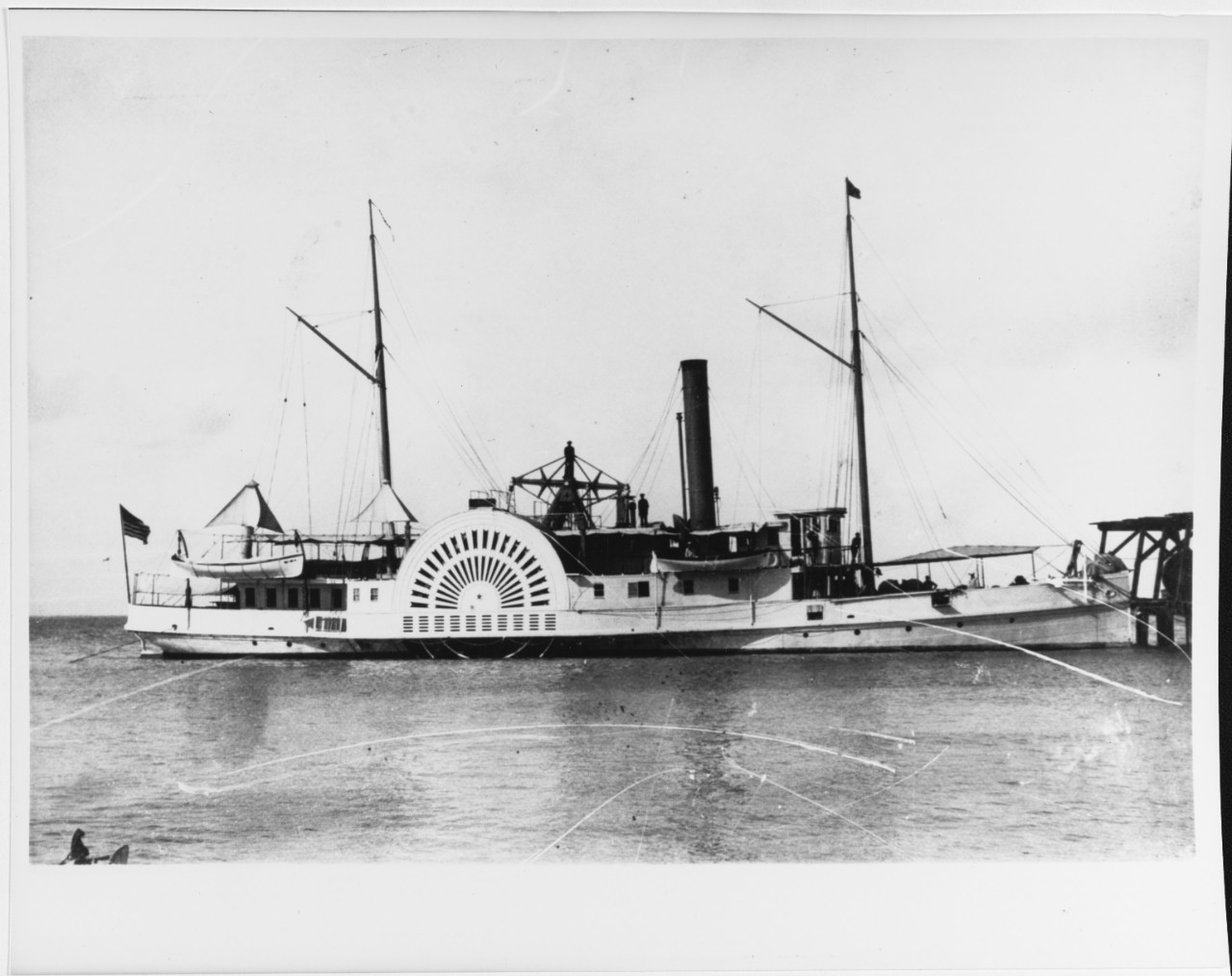

–USS Philadelphia (flagship): This sidewheel steamer was built in Chester, Pennsylvania, by Reaney Neafie, in 1859. The US Navy obtained the vessel in 1861. The Philadelphia was 200 feet in length with a 7.6-foot draft and was armed with two 12-pounder rifles.

–USS Southfield: A 200-foot-long sidewheeler with a draft of 6.6 feet, this steamer could make 12 knots. Englis of New York built Southfield in 1857. The ship’s armament included three IX-inch shell guns and one100-pounder rifle.

–USS Hunchback: This former New York ferry boat was built in 1852 by Simonson of New York and obtained by the US Navy in 1861. The sidewheeler was 179.5 feet in length with a 9-foot draft and could make 11 knots using an engine built by Novelty Iron Works. The vessel was armed with two IX-inch shell guns and one 100-pounder rifle.

–USS Commodore Perry: Formerly a New York ferryboat built in New York by Stack in 1859, this sidewheeler was 144.6 feet in length with a draft of 9 feet. The gunboat was armed with two IX-inch shell guns and two 32-pounders.

–USS Ceres: This sidewheeler was built by Terry of New York in 1856, and purchased by the Navy in September 1861. The gunboat was 108.4 feet long with a draft of 6.3 feet. It could make 9 knots and featured a battery of one 30-pounder rifle and one 32-pounder.

–USS Whitehead: Built in New Brunswick, New Jersey, in 1861, the screw steamer was 93 feet in length with an 8-foot draft. The gunboat was armed with just one IX-inch shell gun.

–USS Underwriter: This sidewheeler was built in Brooklyn, New York, in 1852. Just 103.6 feet in length with a 7.6-foot draft, the steamer was armed with one 80-pounder rifle and one XIII-inch shell gun.

–USS William G. Putnam: This sidewheel tug was built in 1857 and purchased by the Navy in 1861. With a speed of 7 knots, this tug was 103.6 feet in length with a draft of 7.6 feet. It was armed with six 32-pounders and one 24-pounder howitzer.

–USS Valley City: Built by Birdy in Philadelphia in 1859 and obtained by the Navy two years later, this 133-foot long screw steamer could make 10 knots and was armed with four 32-pounders. It had a draft of 8.4 feet,

–USS Delaware: Built in Wilmington, Delaware, by Harlan, this sidewheeler could make 13 knots. The gunboat was 161 feet in length with a draft of 6 feet. The sidewheeler’s armament included four 32-pounders and one 12-pounder rifle.

The squadron’s six other similar ships included: Stars and Stripes, Hetzel, Louisiana, Daylight, State of Georgia, and Chippewa. [22] Goldsborough could bring 19 gunboats with 57 guns to deal with the Confederate naval forces in the sounds. [23]

Goals and Objectives

Burnside’s 80 transports and gunboats rendezvoused in Hampton Roads on January 5. McClellan had previously changed the target of the Burnside Expedition to Roanoke Island. The Union general-in-chief recognized that he wished to strike at Richmond by way of Tidewater Virginia’s rivers and that Burnside could threaten Norfolk from North Carolina.

Burnside’s mission was direct. He, in cooperation with Flag Officer Goldsborough, was to capture Roanoke Island, seize or block canals leading to Norfolk, capture the major ports within the sounds like New Bern, Edenton, and Elizabeth City, capture or destroy Fort Macon on Bogue Banks, and destroy the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad at Goldsboro.

McClellan knew that the canals and railroads were critical to the Confederate war effort. Destroying these transportation systems would break the Confederate supply line and result in a Union victory. Burnside was also advised that if all of the goals above were achieved, he could use his Coastal Division to strike against Raleigh or Wilmington if feasible.

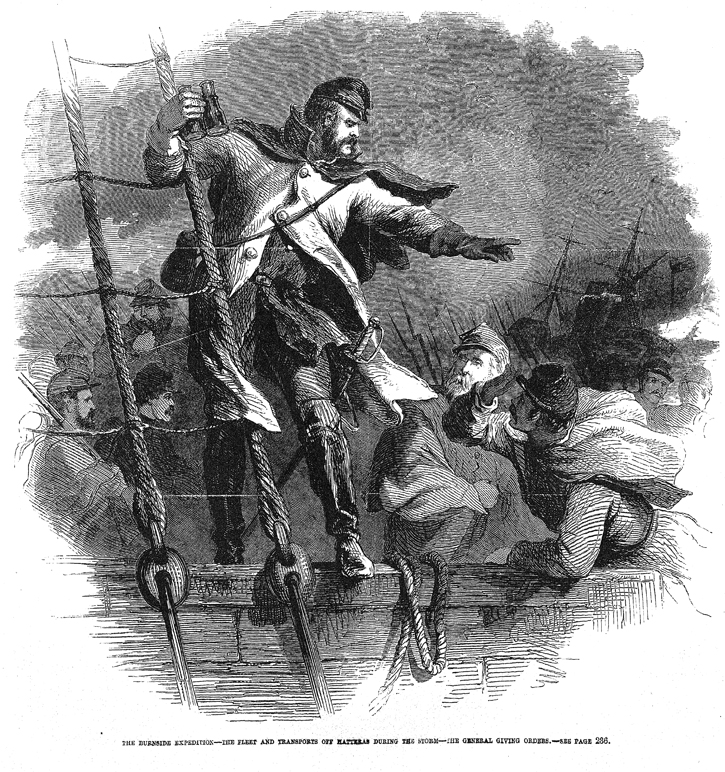

Dangerous Passage

Burnside’s 80 transports and gunboats rendezvoused in Hampton Roads on January 5, 1862, and sailed the next day to Annapolis, Maryland, to pick up tons of supplies, animals, artillery, ammunition, and 12,000 soldiers. On January 9, Burnside arrived with great fanfare, and the armada then returned to Hampton Roads. On the night of January 11, the fleet went to sea. Two days later, the convoy was struck by a heavy gale which endangered many of the ships. Five ships were destroyed or grounded.

Courtesy of the New York State Library.

The City of New York ran aground with its cargo of guns, ammunition, and almost $200,000 worth of supplies. The weather was so bad that the crew members could not be rescued for nearly 40 hours. The Army gunboat Zouave and a floating battery sank without a trace, but with no loss of life. The transport Pocahontas went down with 100 horses.[24] Two officers with the 9th New Jersey, Colonel Joseph W. Allen and Surgeon Weller, died as a result of the storms. [25]

A Waiting Game

When Goldsborough’s squadron joined Burnside’s transports off Hatteras Inlet, another heavy storm struck between January 22-24. Somehow both commands managed no losses during this gale. The soldiers were miserable while waiting to reach into Pamlico Sound. The Ann E. Thompson was struck so hard by the ‘maddening waves’ that the stove in the gallery was knocked over and started a fire which “in an instant heavy black smoke from the greasy floor made its way down into the hold, in which nearly seven hundred men were confined, creating a panic.”

The fires were subdued; however, the experience only added to the soldiers’ misery. They suffered from a lack of proper food. Aboard the troopship Dragon, members of the 9th New Jersey believed that the water was an “unpalatable liquid” and discovered pieces of dead rats deep within the water casks. As one New Jersey soldier stated, “it’s a wonder you are not all sick.” [26]

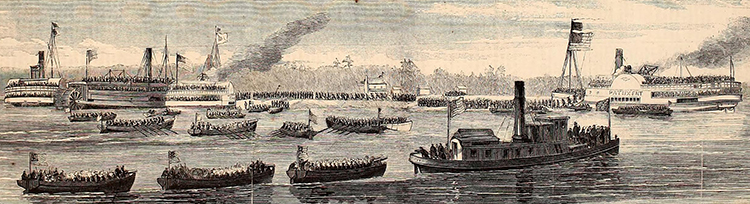

Crossing the Bar

Another great task had to be accomplished in late January and early February 1862. The transports and gunboats had to make their way into Pamlico Sound. The channel was treacherous, and at high tide, the depth at some places was just seven and a half feet. Burnside’s transports and many of Goldsborough’s gunboats needed much more water to access Pamlico Sound. Several large ships had to unload their cargoes at Hatteras and then return North, while others strained to make it through the channel. Ballast, supplies, and guns were off-loaded to lessen a vessel’s draft. Once lightened, some ships were kedged into the sound. Others would run into the bar at full speed in reverse. Then tugs would push the vessels to deepen the channel. By February 5, all of the required ships had made it through the inlet and began organizing for the attack.[27]

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In Awe of the Armada

The entire Union fleet anchored off the southern tip of Roanoke Island by February 5. The next day the weather was so bad that it made it infeasible to launch an amphibious assault. Nevertheless, on February 6, the CSS Appomattox steamed below the pilings to better view the Union armada. Appomattox reported this awe-inspiring site to Flag Officer William Lynch. Lynch, aboard his flagship Sea Bird, was visited by Lieutenant William H. Parker of the CSS Beaufort. They discussed, with a sense of fatalism, the upcoming engagement. They knew that the Mosquito Fleet’s prospects the next day were dim.

After reviewing these unpleasant thoughts, they then drifted into a discussion about Sir Walter Scott’s literary works. They talked and shared their favorite scenes and characters in several of Scott’s novels, especially Ivanhoe. Time passed quickly without care for the future; just the meaning of the noble deeds of the past was important. Soon, the ship’s bell tolled midnight, and Lynch accompanied Parker off the Sea Bird with a brooding farewell: “Ah, if we could only hope for success…..but come again when you can!” Parker, as he rowed back toward his gunboat, thought about “what strangely constituted beings…we are after all. Here were two men looking forward to death in less than 24 hours–death, two, in defeat, not in victory–and yet able to lose themselves in works of fiction.” [28]

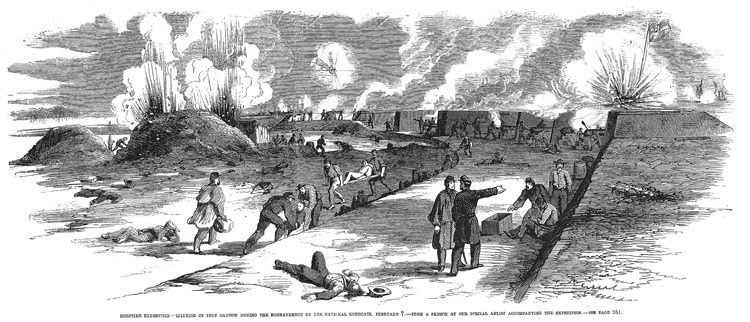

Attack Begins

Such literary discussions drifted far from the reality of the upcoming battle at hand. Continued bad weather delayed Union movements until 9:30 a.m. on February 7. Goldsborough moved his flag from the Philadelphia to the Southfield and hoisted the signal: “Our country expects every man to do his duty.” [29] Goldsborough divided his force into two groups: the first portion led the bombardment, and the rear division towed the army boats ashore. Ashby Harbor was the landing site. USS Underwriter opened the battle by shelling the nearby landscape at 11:30 a.m. No Confederate defenses were discovered, so the landing craft were readied. The first division then concentrated their fire at Fort Bartow.

Mosquito Fleet Swatted Away

The Confederate gunboats remained behind the obstructions as most of the Union naval guns outranged their guns. The CSS Forrest’s engines were struck early in the fight, and the gunboat steamed away to Elizabeth City. The Curlew, striving to bait the Union gunboats past the obstructions, was severely struck by a shell from USS Southfield. The shell went through the Confederate gunboat’s upper deck clear through the ship’s bottom. Lt. ’Tornado’ Hunter became overly excited and tried to save his ship by running it aground. Unfortunately, Curlew grounded in front of Ft. Forrest, which blocked the fort’s ability to fire its guns. Consequently, the fort could not participate in the fight. By mid-afternoon, the Mosquito Fleet had used all of its ammunition. It was a hot action despite the disparity in numbers. Lynch broke off the action and eventually steamed to Elizabeth City.[30]

Gunboat Attack

The Union gunboats primarily focused their fire on Fort Bartow. They thought they had caused great damage to the fort; however, they had not. Fort Bartow could only bear four of its nine guns on the Union warships. Nevertheless, the Confederates scored 27 hits. USS Commodore Perry received eight hits, three hits below the waterline. Hetzel was knocked out of action by a shot between wind and water, and Hunchback was struck eight times. Valley City was also badly hit by a shell. [31]

Ashby Harbor Landings

The gunboats’ actions enabled the Union to begin landing troops unmolested. Small steamers towed the boats ashore and then released them as vessels glided toward the shore. More than 10,000 men landed that afternoon. Goldsborough thought that the Confederates should have fortified Sand Point or should have opposed the landings somehow. Hidden in the nearby woods was Colonel J. V. Jordan with 200 marksmen and two cannons.

Jordan did not allow his men to fire. It was a missed opportunity that could have greatly disrupted the landing operation. Instead, Commander Stephen Rowan of the USS Delaware noticed the glint of gun barrels and peppered the woods with canister and grapeshot. The Confederates retreated to their main defensive line. All of the Coastal Division troops camped for the evening, planning to advance in the morning.

Vacuum in Leadership

Unfortunately for the Confederates, their most aggressive officer and commander was not available as the Federals completed their landing. Henry Wise was ill in bed at the Nags Head Hotel with pneumonia. So, Col. Shaw assumed command of the Roanoke Island defenses. Shaw had no military experience, and many believed, as Captain Henry McCrae stated, that he “was not worth the powder and shot it would take to kill him.”[32]

Shaw’s concept for the island’s defense was to rely on the central redoubt that blocked the main road. Because this earthwork was 80 feet long on a narrow causeway, Shaw could only place 400 men in the defensive position. He then deployed the remaining 1,000, about 250 yards behind the earthworks, to act as a reserve. At the last minute, Shaw received some reinforcements in the guise of elements of the 46th Virginia. Shaw did not place skirmishers to guard his flanks as he believed, as did everyone else, the swamps could not be transversed.

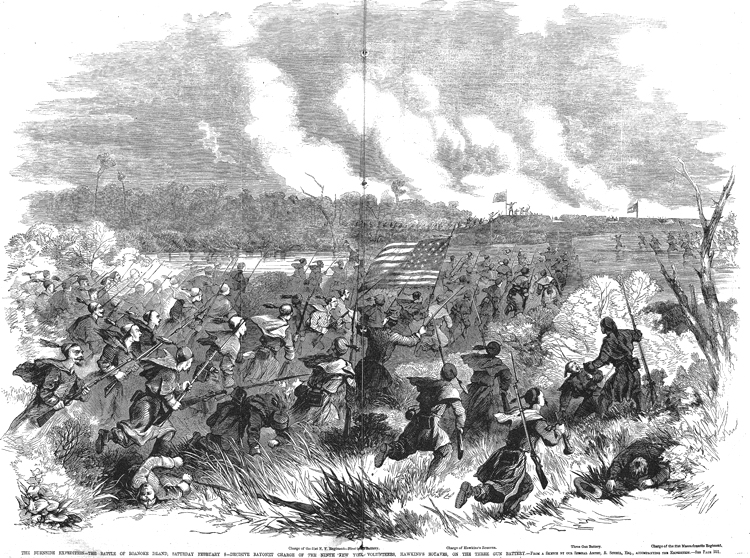

The Land Attack

Intermittent cold rains throughout the night had made for a miserable night for Burnside’s soldiers. Nevertheless, early on the morning of February 8, Burnside ordered the advance. The Confederate works were about a mile away from Ashby Harbor. This single track was muddy, filled with bog holes, and very narrow, which only allowed for a double-file advance. General Foster’s First Brigade led the advance. At the forefront of Foster’s column was the 25th Massachusetts, and by about 9:30 a.m., they engaged the enemy. The Massachusetts troops were aided by three boat howitzers commanded by Midshipman Benjamin H. Porter which leapfrogged in support of the 25th’s advance. The advance became bogged down in the 70-yard clearing the Confederates had cut to give them a clear field of fire.

After almost two hours of volleys being traded in the thick black smoke. Foster ordered forward the 10th Connecticut to replace the 25th Massachusetts; however, he also realized that he could not effectively advance on such a constricted front. Accordingly, he sent the 23rd and 27th Massachusetts regiments into the swamps toward the Confederate left.[33]

Into the Swamps We Go

Likewise, as Jesse Reno reached toward the front lines, he ordered his entire brigade — 9th New Jersey, 21st Massachusetts, and 51st New York — “off the road and into the swamp.” Captain Drake of the 9th New Jersey remembered, “to turn the enemy’s right. The men waded through waist-deep in mud and water, occasionally raising their cartridge boxes and haversacks to keep that from getting wet. A worse place for men to move and maneuver would be difficult to imagine. The Confederates, having no idea that any attempt would be made to enter the swamp at that point, had trained their guns in the other direction, for which we were thankful.”[34]

George Washington Whitman wrote his brother the poet Walt, “We worked our way on their right flank through a thicket that you would think it was impossible for a man to pass through.” [35]

Victory is Ours

As the units of Reno and Foster first emerged from the swamps, Colonel Rush Hawkins, a wealthy New York attorney and member of the 9th New York, implored Gen. John Foster for permission to make a frontal assault against the Confederate works. Foster agreed. Hawkins ordered his men, known as the Hawkins Zouaves, rapidly forward with the cry of ‘Zou-zou-zou’ as they reached the Confederate parapet. The Zouaves claimed that their bayonet charge had won the day for the Union.

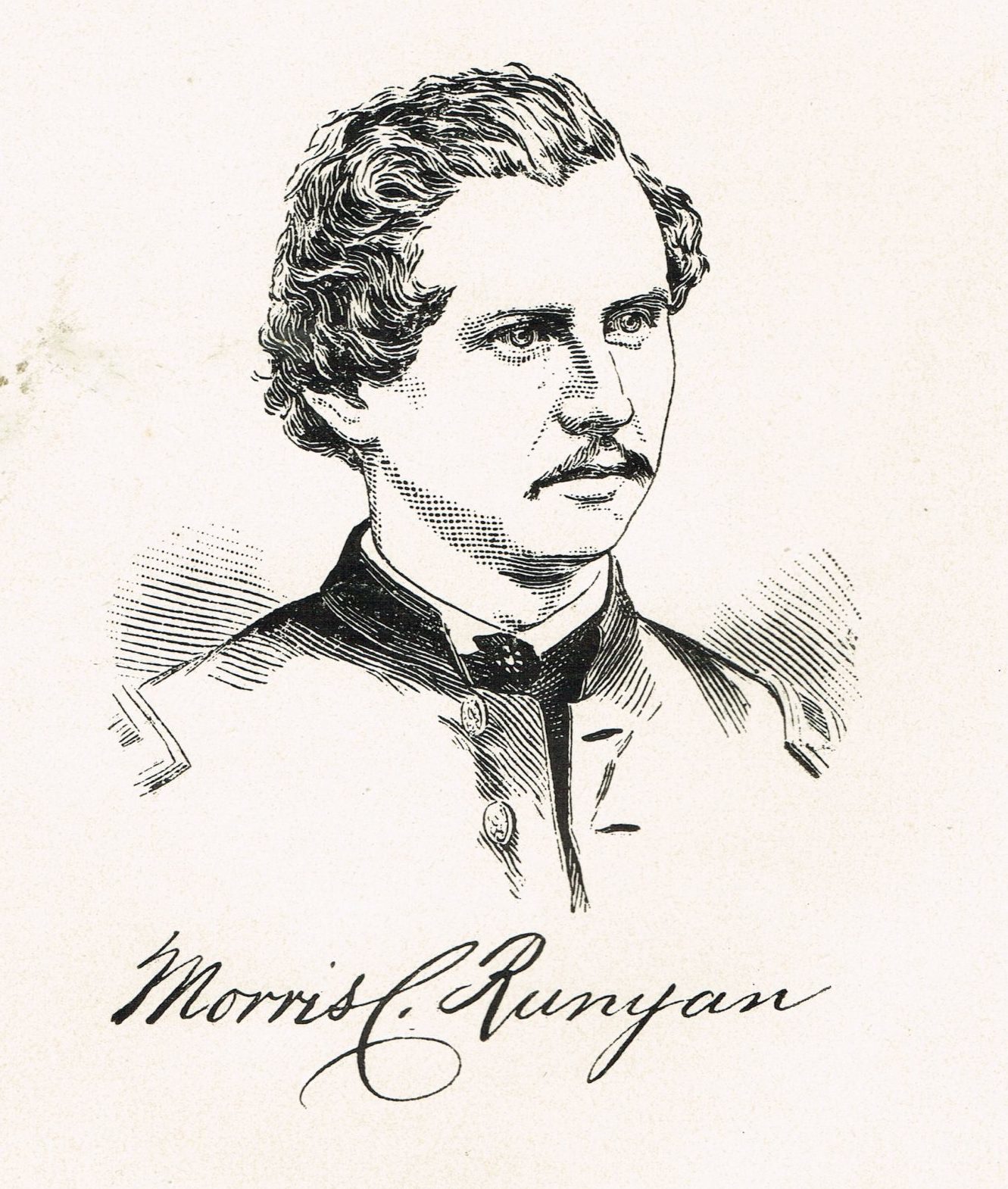

Other units disavowed (this argument would last for the next 40 years) the 9th New York’s claim as it was actually the 51st New York and 21st Massachusetts that first planted their flags on the Confederate earthworks. The 9th New Jersey claimed equal glory for their flank attack. The marsh assault at Roanoke Island prompted Captain Morris Runyan to call his unit the New Jersey Muskrats [36] and Capt. Drake referred to the regiment as the Swamp Rats.[37]

The battle was now over. Colonel Shaw, who had no contingency plan to stem any breach in his defensive line, surrendered more than 2,500 men, including recent reinforcements and all of the men in the forts. By early afternoon, December 8, 1862, Burnside had achieved his greatest victory that gave control of the North Carolina sounds to the North.[38]

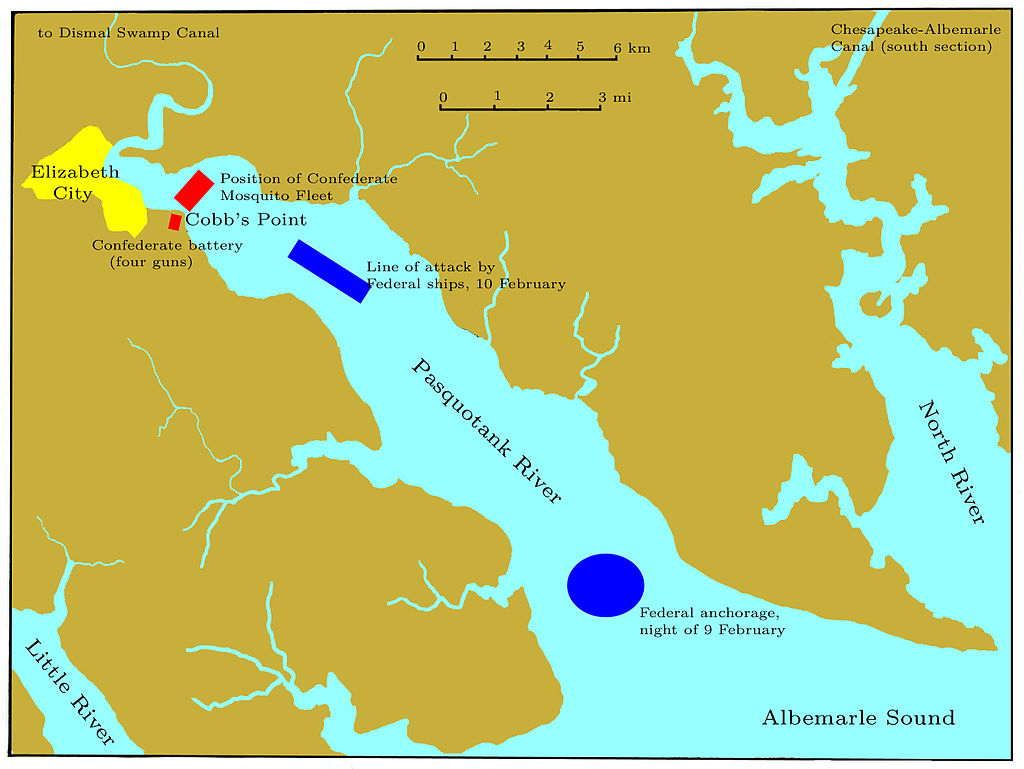

Mosquito Fleet Survived to Fight Another Day

On February 7, 1862, Lynch’s North Carolina Squadron had bravely engaged the Federal fleet. CSS Curlew was lost, and CSS Forrest had to undergo significant repairs. Nevertheless, the Mosquito Fleet retreated into Albemarle Sound and then up the Pasquotank River to Elizabeth City near the Dismal Swamp Canal entrance. Lynch, having limited ammunition, could have escaped up the Dismal Swamp Canal. Instead, he sent CSS Raleigh to secure more ammunition from Gosport Navy Yard and began preparations to defend Elizabeth City. The flag officer believed that if he left the town it “would have been unseemly and discouraging…as I had urged the inhabitants to defend it to the last extremity.”[39]

Confederate Preparations

With only 10 rounds per gun, Lynch anchored his defense on Cobb’s Point Battery. This defensive work was manned by local militiamen and contained four 32-pounder guns. He placed the schooner Black Warrior, with two 32-pounders, off the battery. He then stationed the rest of his fleet across the Pasquotank River. There, Sea Bird, Ellis, Appomattox, Beaufort, and Fanny awaited their fate.

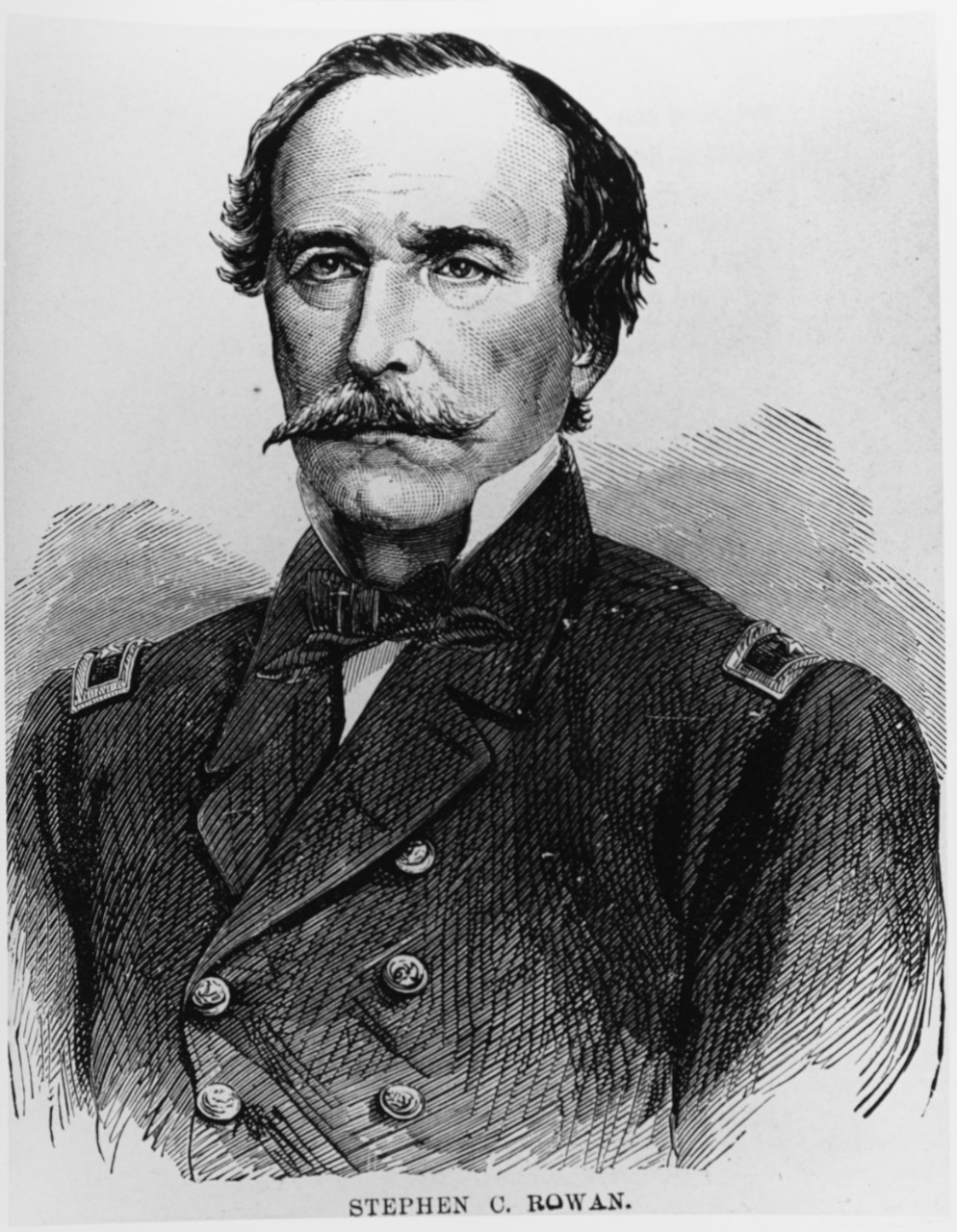

Federal Approach

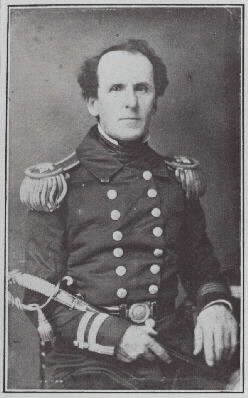

Commander Stephen C. Rowan was sent by Flag Officer Goldsborough to terminate the Mosquito Fleet once and for all. Rowan, an Irish immigrant and graduate of Miami University, was appointed a midshipman in the US Navy on February 1, 1826, at the age of 17. He served as the executive officer of USS Cyane during the Mexican War. Rowan commanded the gunboat USS Pawnee during the Union’s failed attempts to save Fort Sumter and Gosport Navy Yard. Rowan played an important role in the August 28-29, 1861 capture of Hatteras Inlet and was second-in-command to Flag Officer L.M. Goldsborough during the Roanoke Island Expedition. [40]

A Decisive Plan

Rowan’s force consisted of 14 gunboats containing 37 guns. The steamers included Delaware, Underwriter, Commodore Perry, Hetzel, and Whitehead. The Union vessels arrived at the mouth of the Pasquotank River late on February 9. The flotilla’s commander called all of his officers to his flagship Delaware and made plans for the next day. He informed them that they only had 20 rounds of ammunition per gun. Consequently, their movement up river would be a reconnaissance in force. If Rowan felt the situation was favorable it would be “converted into an attack.” He stressed that the next day’s struggle should be fought “hand to hand” to “economize ammunition.” [41]

At dawn the next day, February 10, the Federal gunboats steamed up the river in three columns. Flag Officer Lynch, expecting the Union attack to focus on the Cobb’s Point Battery, inspected the fort and found that the militia had “All run away.” Lynch ordered Lt. Parker to use his men to man the fort. Parker called the battery “a wretchedly constructed affair” with four 32-pounders “badly mounted.” Only two guns could be trained on the approaching enemy. Parker left orders for Beaufort’s pilot to “slip the chain and escape through the canal to Norfolk.” [42]

“Dash At the Enemy!”

At 8:30 a.m., the Federals came within sight of Lynch’s command. Rowan ordered his ships full throttle forward with the signal “Dash At the Enemy!” They passed Cobb’s Point Battery and then sent a shell into Black Warrior. The Confederates set fire to and abandoned the schooner. Lieutenant Charles Flusser of Commodore Perry sped toward Sea Bird. “I fired a nine-inch shell at her,” Flusser later wrote, “which struck her amidships at the water line, passing through her as if so much paper. I then called away boarders and ran for her, my men picking up their muskets, pistols, and cutlasses for a hand to hand fight.”

Flusser tried to stop the momentum of his gunboat as Sea Bird had surrendered; however, Commodore Perry smashed into the Confederate flagship. Sea Bird then sank. CSS Fanny was boarded and captured by USS Delaware and the Ceres closed onto CSS Ellis. The gunboat’s commander Lieutenant James W. Cooke ordered most of his men to abandon ship while he and a few others tried to repel the Union boarders. Cooke was seriously wounded and Ellis became a prize. The Beaufort and Appomattox raced toward the Dismal Swamp Canal’s South Mills lock. The Appomattox was two inches too wide to make it into the lock and was scuttled by its commander Lieutenant Charles Carroll Simms. The only Union gunboat damaged was the USS Valley City. The shell had passed through the magazine and entered a locker near the magazine, starting a fire which was calmly controlled by the ship’s gunner John Davis. [43]

Aftermath

The citizens of Elizabeth City burned part of their town and the Federals destroyed two vessels on the stocks. The gunboat Forrest, which was under repair, was burned. Edenton, North Carolina, was captured on February 12 and the entrance to the Albemarle & Chesapeake Canal was blocked by an expedition led by Lieutenant William Jeffers of USS Underwriter using two schooners captured at Edenton and an old dredge on February 14, 1861. [44]

In a matter of a week, the Union used a well-conceived combined operation to control all of the upper North Carolina sounds. The Unionists realized that the capture of Roanoke Island and the surrounding sounds drove a stake into the heart of the Confederacy.

The Confederacy would never truly recover from the loss of Roanoke Island which should have been one of the most heavily fortified places in the South. Instead, it was considered a backwater by many government officials in Richmond. Perhaps Major General Benjamin Huger should receive the most blame as he failed to provide adequate resources to defend one of the approaches to Norfolk and Portsmouth. His fixation on defenses in Hampton Roads rather than in the North Carolina sounds was his greatest error of the war. He had the available resources to make Roanoke Island the Gibraltar of the South. Yet, Huger lacked the strategic vision to do so.

Endnotes

1. Davis, Archie K., Boy Colonel Of The Confederacy–The Life And Times Of Henry King Burgwyn, Jr.. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1985, pp. 89-90.

2. Faust, Patricia L., ed., Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia Of The Civil War, New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1986, pp. 301-302.

3. IBID, p.14.

4. IBID, pp. 361-362.

5. Official Records Of The Union And Confederate Navies In The War Of The Rebellion (Hereinafter referred to as ORN.) Washington: Government Printing Office, 1897, Ser.1, Vol IV, p. 682.

6. Faust, pp. 838-839.

7. Faust, p. 374.

8. Scharf,J. Thomas, History Of The Confederate States Navy. New York: Gramercy Books, 1996, p. 384.

9. Hill, Daniel Harvey, A History Of North Carolina In The War Between The States, Volume I – Bethel to Sharpsburg. Raleigh, North Carolina: Edwards & Broughton, 1926, p. 207.

10. Faust, pp. 387-388.

11. Hill, p. 263.

12. Day, D.L. My Diary Of Rambles With Burnside’s Coastal Division. Privately printed, Milford, Massachusetts, p. 35.

13. Still, William N., Jr., Iron Afloat: The Story Of The Confederate Armorclads. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1985, p.151.

14. ORN, Ser.1, Vol. 9, p.129.

15. Silverstone, Paul.H., Civil War Navies 1855-1883. Annapois, Maryand: Naval Institute Press, 2001, pp.179-181.

16. ORN, Ser, I, Vol.6, p.428

17. Faust, p.314.

18. Daly, Robert W., ed., Aboard The Monitor:1862. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute Press, 1964, p. 155.

19. Faust, pp.96-97.

20. Faust, pp. 282, 556, 623.

21. Browning, Robert M. Jr., From Cape Charles To Cape Fear: The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron During The Civil War. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 1993, pp. 21-23.

22. Silverstone, pp.67-73.

23. ORN, Ser. 1, Vol. 6, pp. 551-552.

24. Burnside, “Burnside’s Expedition,” Personal Narratives of Events in the War of the Rebellion, Being Papers Read before the Rhode Island Soldiers and Sailors Historical Society, 2d ser., no. 6, Providence: N. Bangs Williams, 1882, pp. 18-19.

25. Drake, J. Madison, Ninth New Jersey Vols. Elizabeth, New Jersey: Journal Printing House, 1889, pp.26-27.

26. IBID, pp. 31-33.

27. Trotter, William R., Ironclads And Columbiads: The Civil War In North Carolina The Coast. Winston-Salem, North Carolina: John F. Blair, Publisher, 1989, pp. 71-73.

28. Parker, William Harwar, Recollections Of A Naval Officer. New York: Charles Scribners’ Sons, 1883, pp. 228-229.

29. ORN, Ser. 1, Vol.6, p. 569.

30. IBID, p. 594.

31. Browning, p. 26

32 Barrett, The Civil War in North Carolina, p. 74.

33. Harper’s Pictorial History Of The Civil War. New York: The Fairfax Press, 1993, pp. 245-46.

34. Drake, p. 42.

35, Loving, The Civil War Letters Of George Washington Whitman, p. 76.

36. Runyan, Morris R., Eight Days With The Confederates. Princeton, New Jersey: Wm. C. C. Zapf, Printer, 1896, frontispiece.

37. Drake, pp. 43-45.

38. Harper’s Pictorial History of The Civil War, p. 246.

39. ORN, Ser 1, Vol. 6, p. 595.

40. Faust, p. 646.

41 ORN, Ser. 1, Vol. 6, p. 603.

42. Parker, pp. 234-238.

43. ORN, Ser. 1, Vol. 6, pp. 607-621.

44. IBID.