In honor of Armistice/Veterans day I thought I would tell one local man’s World War I story. That man is Henry Redmond Hendren. Henry was born in Norfolk, Virginia on October 4, 1900 making him just 13 when the war started in Europe in July 1914.

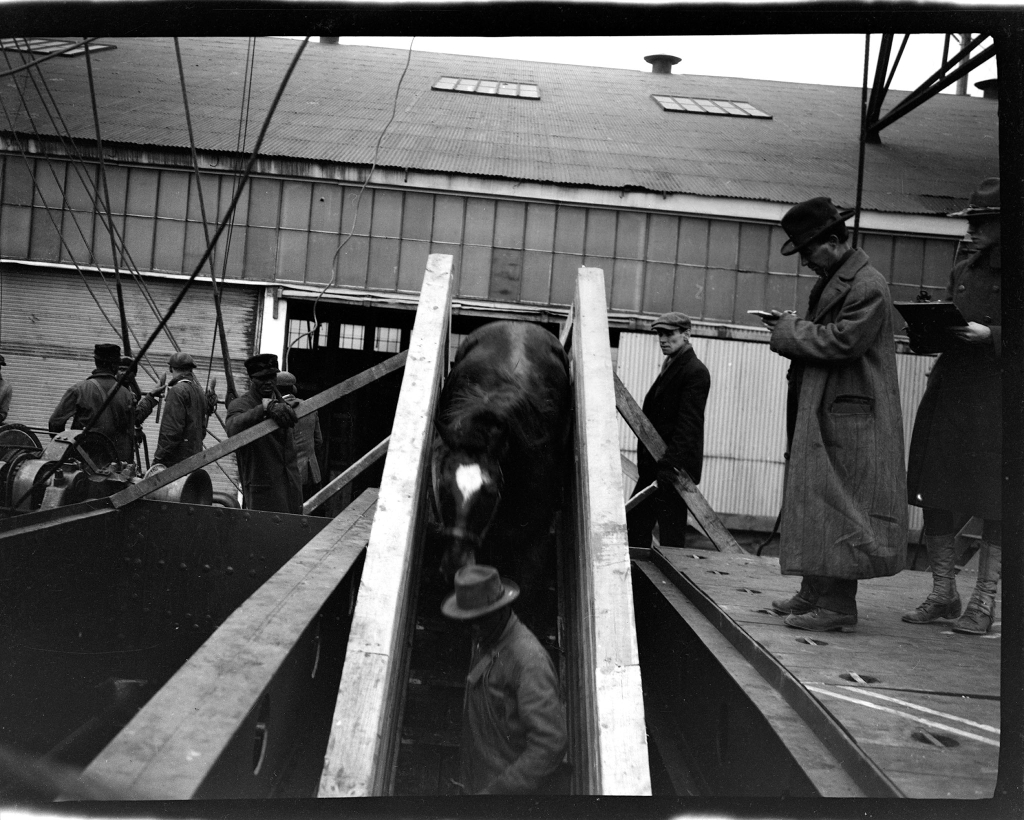

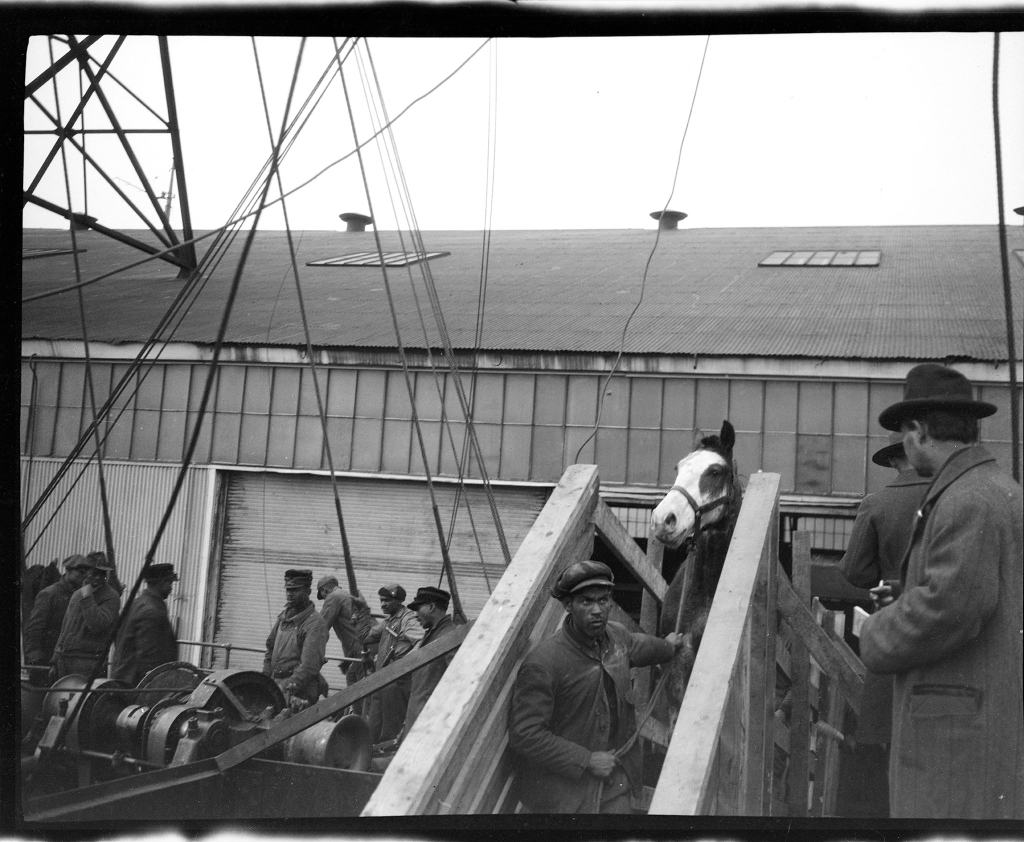

For those of you who aren’t aware of Newport News history in World War I, here’s a little bit of backstory to help explain what happened to Henry. Just a few months after the start of World War I the British, who still relied heavily on the use of horses and mules to transport matériel and wounded on the battlefield, had exhausted Britain’s supply of animals. They looked to the United States to provide this necessary resource and established facilities to house and transport the animals—the largest in Missouri. Thank to our extensive railroad infrastructure and protected port, Newport News was chosen as an embarkation facility. Between late November 1914 and the end of the war Newport News became the biggest and most important shipper of horses and mules to the British army in Europe.

With both a British Remount Station (which could accommodate 5,000 animals) and the American Animal Embarkation Depot No. 301 at Camp Hill (built to accommodate 10,000 animals) located in Newport News hundreds of ships came to the port to ferry the animals to European battlefields. By the end of the war nearly 500,000 animals had been transported through Newport News.

In January of 1916, at the age of 15, Henry joined the crew of a British livestock transport ship called Esmeraldas as a muleteer. The 4,678 ton Esmeraldas was operated by the Pacific Steam Navigation Company in the service of the British Admiralty and traveled between Newport News and Liverpool with shipments of horses and mules. Because of the secrecy surrounding the shipments, its difficult to know exactly how many voyages Henry participated in.

On January 28, 1917 Esmeraldas sailed from Newport News with a cargo of 950 horses. It arrived safely in England, unloaded its valuable cargo, took on ballast and began its return voyage to Newport News in mid to late February–but it never arrived. By the end of March everyone feared the worst, especially when a veterinarian named Clarke, who had missed the ship’s departure and was forced to return on a passenger ship had arrived back home quite some time before.

As it turned out, around 2:00 AM on March 10th while 420 miles off the Azores the Esmeraldas had been overtaken and captured by the German commerce raider SMS Möwe. Upon overtaking the vessel, Möwe signaled Esmeraldas to surrender which it backed up with a shot across the bow. Instead, the crew aboard Esmeraldas fired up the ship’s engines to full speed ahead. Displeased, the Möwe fired straight at Esmeraldas and the shot was so close as it whistled overhead that the concussion knocked the officers on the bridge down.

The ship was quickly surrendered and the Germans clambered aboard and transferred the Esmeraldas 58 crew, which included 54 American muleteers, and 60 passengers onto the Möwe. The Esmeraldas was scuttled with three explosives and the Möwe continued on her way. Later that same day Möwe tangled with the armed New Zealand Shipping Company merchant ship Otaki. The ship, which was protected by only one gun, managed to fire off nine shots eight of which hit the Möwe. The brief battle ended with the sinking of Otaki but she had done enough damage that Möwe was forced to return to Germany for repair.

Möwe, one of Germany’s most successful raiders caught and sunk about forty allied ships during two brief voyages. The battle with Otaki pretty much ended her raiding career with only two more vessels caught and sunk on her way back to Germany. When Möwe arrived at Kiel she had about 593 prisoners on board. They remained at Kiel for four days and were then sent to Durmen. Several weeks later they were taken to a prison camp near Brandenburg. Prisoner Walter Smith of Norway, Connecticut describes ill treatment of the men in the camp: “they pushed us and shoved us a good deal and called us swine and some other things” and stated that their food consisted of “one chunk of bread daily and turnip soup. That turnip soup was good water spoiled.”

The next time we hear of young Henry is in a Washington Post article dated February 10, 1918 discussing how prisoners in some of the camps were not receiving any mail from home. In the article Henry, who was being held in a camp at Lubeck, asked E. G. Wilson of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) to notify his mother of his whereabouts. His letter also gives us some indication of Henry’s difficult situation. Although his letter doesn’t mention it, Lübeck was the site of a huge iron foundry and many of the prisoners were put to work there.

“I was certainly glad to hear from you. I am in need of your assistance very much. I have written to the British Red Cross several times for bread, but have not received a reply. I wish you would kindly notify my mother of my whereabouts” he said “I have written to her several times, but have not received a reply. The address is 210 Maple Avenue, Berkeley, Norfolk, Va. I saw in one of my mates’ letters that you were from Charlotte, N.C. I am from Virginia. I would like to correspond with you, as it is lonely here not receiving any mail and others receive letters. I am sixteen years old. It seems very young to be a prisoner-of-war, but it was not my fault. I was a member of the Young Men’s Christian Association in Norfolk, Virginia. I would like to hear from you soon. Hoping to be your friend.”

Shit. Hang tight. This is a child in a German prison camp. I need to compose myself.

Henry spent nearly two years as a prisoner-of-war. When the Esmeraldas was caught he was just 16. He celebrated two birthdays in a German prison camp and had only been 18 for a month when the armistice ended the fighting. Finally released from the prison camp in January 1919, Henry was sent to Denmark and then to Liverpool where he boarded the RMS Carmania bound for New York. He arrived back in the United States February 11, 1919.

If you would like to learn more about Newport News and its role in transporting horses and mules in World War I visit these sites. Mark St. John Erickson’s article has excellent information and images of the British Remount Station.

Check out this great blog post to learn more about prisoners of war and the iron foundry at Lübeck: https://palmerww1powtrail.wordpress.com/2017/04/09/hochofenwerk-lubeck-the-worst-factory-in-the-whole-of-germany/