While working on researching one of the objects in the upcoming Sailor Made exhibition I stumbled across some interesting history—but its discovery also presented a bit of a dilemma for us. The piece is a Pacific Northwest Coast Tlingit halibut hook. I don’t know if most of you have ever seen a fishhook like this, but it really is super cool (especially for those of us who are closet anthropologists!).

Most native-made fishhooks are a beautiful combination of form and function designed to attract a specific species of fish. While they might appear decorative because of the materials used, for the cultures that used them it was really all about functionality. This just isn’t the case with Tlingit halibut hooks. While their V-shaped hooks were perfectly designed to catch halibut, they also featured symbolism intended to secure supernatural assistance to ensure their catch, protect the fisherman at sea and guarantee his safe return to the village.

I guess part of the reason for feeling the need for supernatural assistance was that fishing for halibut could be a seriously dangerous undertaking. It required the fisherman to leave the safety of the village and head several miles out into the open ocean, in a canoe, in the late winter and spring—a time when Alaskan waters are often rough and subject to sudden squalls.

The hooks are truly fantastic with the upper arm carved with animals, birds, human figures, sea creatures and other symbols. We have six hooks in the collection so I chose the one I thought was the coolest. It features a three-quarter view of a standing man with a killer whale parked on his head. Across his chest and stomach he holds a double-bladed fighting knife (for a while I suspected the hook might have been from the Haida culture, but the presence of this weapon convinced me it was Tlingit).

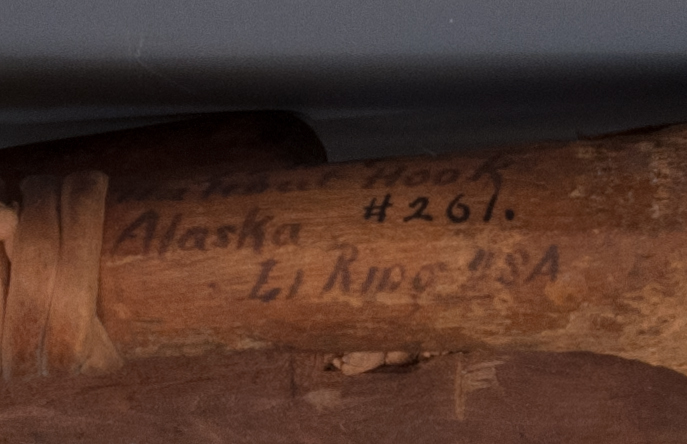

The hook carries an inked mark I didn’t fully understand until I stumbled across an article by Jonathan Malindine, Assistant Curator for Archaeological and Ethnographic Collections at the Department of Anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. The mark is “9104, Halibut Hook, Alaska Lt. Ring USA.” It also carries the inked number #261, but in a different hand. Obviously, this is simply information identifying the hook and I assumed it was done by the person who acquired it, but it turned out to be different than I expected.

The surprise came on page four of an article by Mr. Malindine in the journal Human Ecology. It was a picture of hook with a similar inked inscription: “9103 Halibut hook Alaska Lt. Ring USA.” Needless to say, the discovery stopped me dead in my tracks. The hook in the article is from the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. After a few moments of sheer panic that involved visions of the NMNH staff swooping in with paratroopers to take the piece away, the more rational side of my brain intervened. There had to be a logical reason the piece was no longer in their collection, but I will admit to having my fingers crossed that it wasn’t because of a theft (if so, I would feel ethically bound to let them know we have it). So, I put my detective hat on and went to work.

After a bit of searching I was able to locate the online database for the Anthropology collection at NMNH. It was a little difficult to navigate at first, but by using the most simplistic search I could think of, 9103, I found the hook I was looking for and it helped illuminate some really great history about the piece in our collection. Thankfully, NMNH also attaches images of their accession registers to their object records and those images helped us fill in the story of how the object left their collection.

According to their register the hook had been collected by Lt. Franklin M. Ring of the US Army and had been donated by Lt. Ring, with other items, to the NMNH in November/December 1869. Further research told me that Ring had been part of a detachment of Battery E, 2nd U.S. Artillery under Captain Charles H. Peirce which established Fort Wrangell on May 5, 1868. The establishment of the fort was a direct result of the purchase of Alaska in 1867. South of the fort was a Tlingit village of about 35 houses and 500 inhabitants which may be where Lt. Ring acquired the items he donated to the Smithsonian.

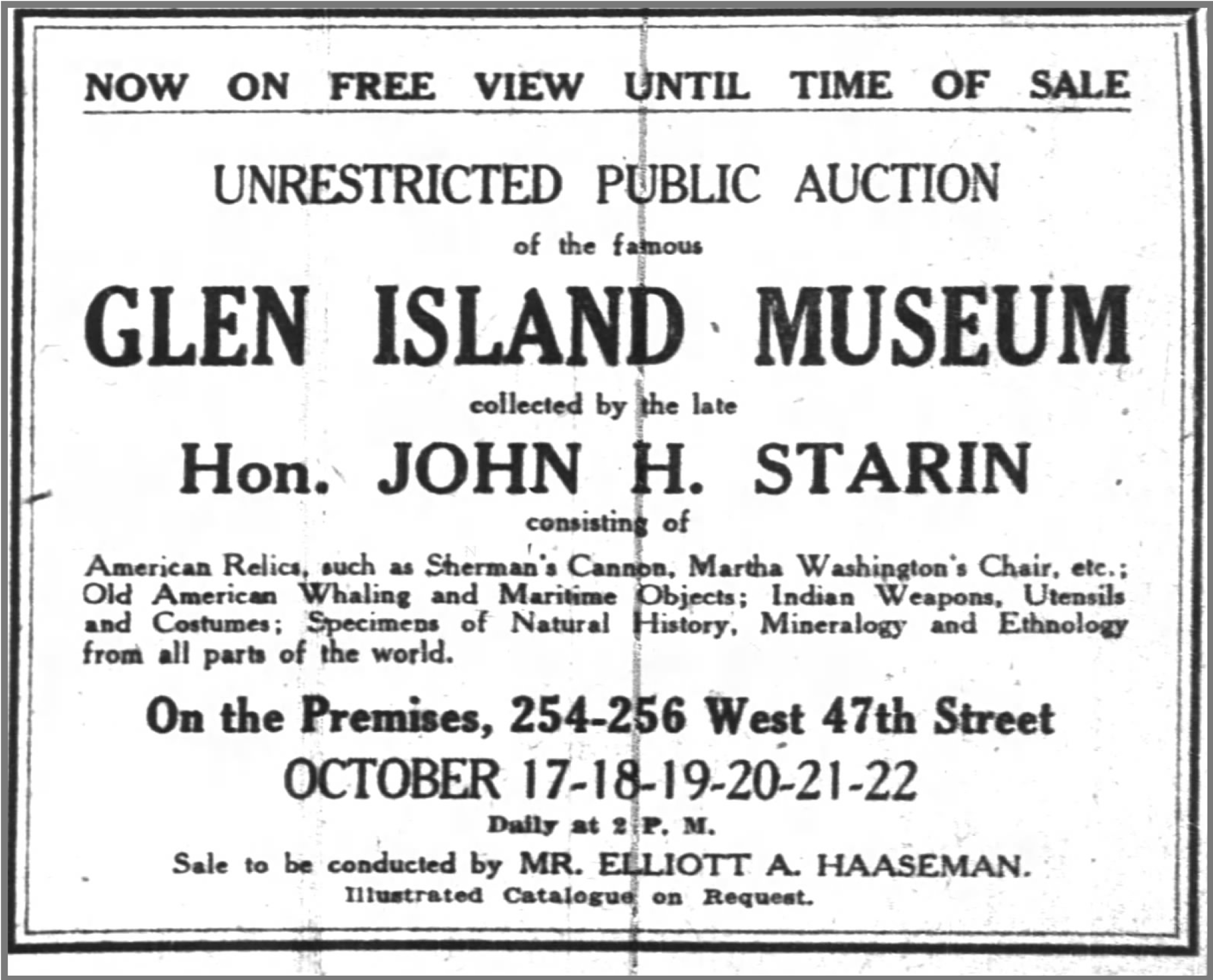

The record for our hook was marked in a later hand with the words “Glen Is. Mus N.Y.” The day after my discovery I relayed the story to my staff and they hit the ground running and discovered that the Glen Island Museum had been assembled and operated by John Henry Starin, the US Representative for New York and founder of a resort on Glen Island, which apparently was America’s first amusement park. Starin died in 1909 and the museum closed at some point after that. In 1915 the museum’s collection was sold to Mr. Harry Hagerty and in 1921 the collection was sold at public auction. We aren’t sure what happened after 1921, but in 1937 one of our buyers, Isabel Redpath, purchased a collection of several hundred items that all appear to have been a part of the Glen Island Museum collection (many of the items bear numbers similar to the #261 that appears on our hook).

Both auctions were very well advertised so I’m pretty sure that if the hook had been part of a loan to the Glen Island Museum the Smithsonian would have claimed it back pretty quickly. Whew! Crisis averted.

At this point I have to say that this is one of the reasons I love my job. It seems like every day reveals a new historical surprise or problem to be solved. Every day is a learning and teaching experience and I can’t imagine that anyone could have a job as cool as mine!