On Saturday we hosted a behind the scenes tour for Hudgins Construction (they very nicely re-graveled our boat building shed so we could easily move and store objects in there). There were a lot of families involved so I programmed two different tours in order to show the kids objects I hoped they might find entertaining (an image of seasick passengers, an early 17th century version of a blokart, a Viking sword, you get the idea).

One of the pieces I showed them was our 1645 Dutch whaling painting by Bonaventura Peters which I supplemented with an engraving of a beached whale on the Dutch coast. As I researched the image, I discovered the reason for its creation was quite fascinating and revealed something I didn’t understand about the weird proliferation of 17th century images of whale strandings.

I won’t bore you with the incredibly long title—which is in Latin and Greek—but the image shows war hero Ernst Casimir I, Count of Nassau-Dietz, visiting the site of a sperm whale stranding that occurred on the coast of North Holland between Beverwijk and Wijk aan Zee (that’s the area where the North Sea and the English Channel meet) in January of 1601. Apparently, tourism to see stinky dead whales was quite the thing in the 16th and 17th centuries. In the image, you can see Casimir and his entourage standing front and center (he’s the guy with the large feather in his hat). If you look closely, you can also see he has a large handkerchief near his face. His visit occurred about two weeks after the whale came ashore so you can imagine the smell must have been pretty intense.

The engraving makes the event look more like a carnival than the gag and vomit-fest you know it truly was. There are thousands of people streaming along the shoreline to see the whale, while other more adventurous souls, obviously those with Anosmia, are investigating the whale up close and personal. Two men are sticking a sword in its blow hole (or maybe it’s his ear?), measuring its length, and even climbing on the carcass like it’s a jungle gym (I wouldn’t want to be standing on this thing when the gases associated with decomposition ruptured the whale’s skin—I gag just thinking about it!).

To commemorate the visit and prove he witnessed the event, the artist, Jan Saenredam, has placed himself to the left of Casimir. He’s easy to spot—there is a barrel and board in front of him and he is actively drawing the whale.

While the image is most definitely documentary in nature—Saenredam even includes images of the entrails–what struck me as really interesting (aside from the huge number of people who actually WANTED to see a really big stinky dead fish) is that apparently the beaching of a whale in the 17th century was considered to be an omen of impending disaster (if that’s true I’m not sure I’d want to be anywhere near it!), anything from military losses to natural disasters.

To reflect this belief, Saenredam has included some interesting imagery across the top of the engraving. While some of the images document events that actually occurred, most are simply reflections of Dutch fears and uncertainties about the wars raging around them (this stranding occurred during the Eighty Years War and Anglo-Spanish War) and their potential to cause a reversal of national fortunes.

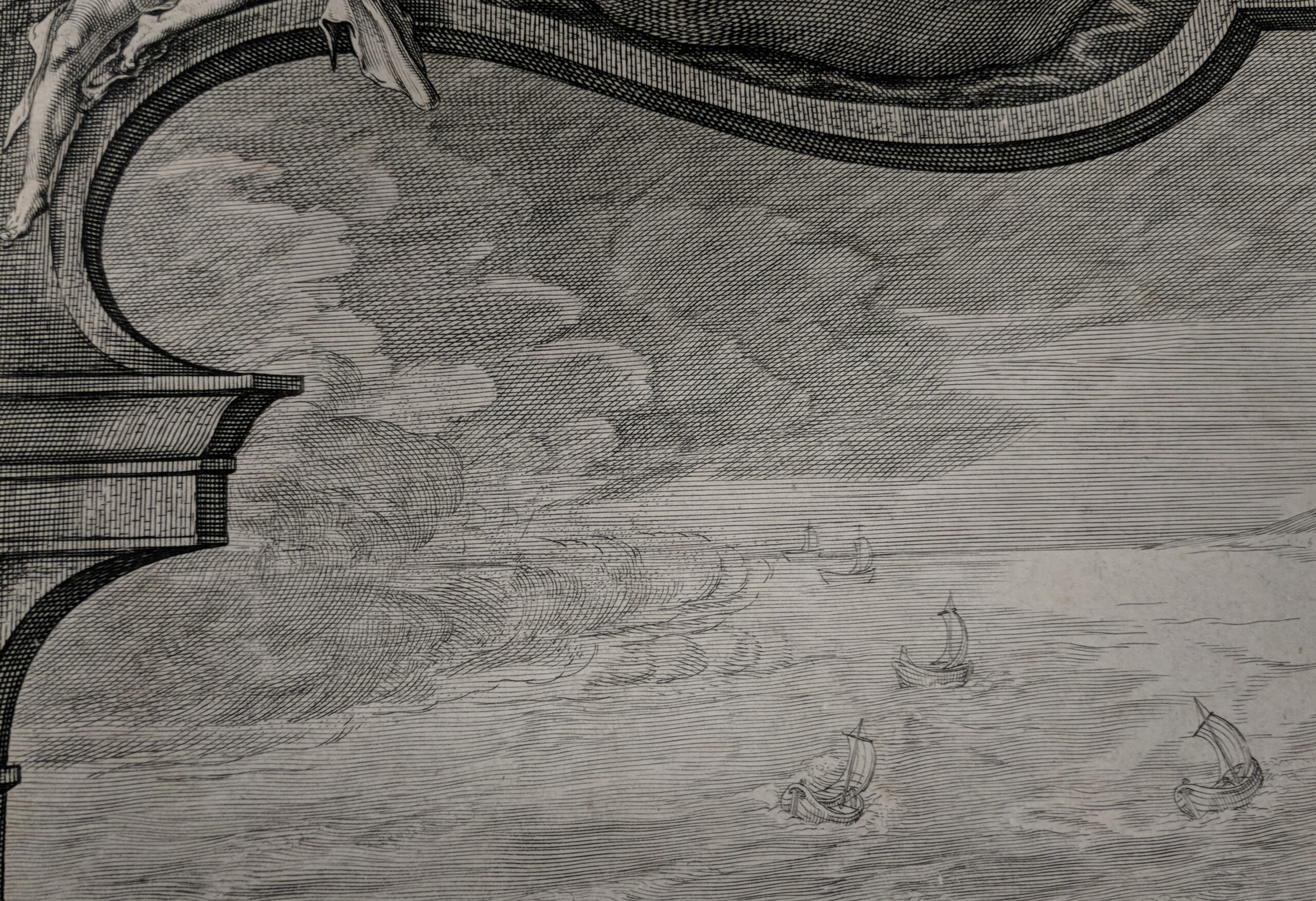

At the left, Saenredam includes the rather obligatory view of an old and serious looking Father Time to illustrate the feeling that time was running out for the Dutch Republic. Beneath him is a depiction of a severe storm headed for the coast. Apparently there were reports coming out of Spain that a large armada was about to sail for the Netherlands. The reports actually had some basis in reality as a massive assault (10,000 men strong) was launched by Spain on the port of Ostend in Flanders in January 1602. While this particular assault was not successful, the siege would last another three years and is considered to be one of the longest and bloodiest sieges in world history.

Moving to the center, Saenredam reinforces the populace’s concern over the Dutch military situation by including an image of a rearing lion holding a sword and arrows (the symbol of the Dutch Republic) caged within a wattle fence.

The disaster allegory continues with images representing natural disasters or phenomena that occurred around the time of the stranding. There are three very distraught-looking moons and a partial solar eclipse that document an annular eclipse that occurred on December 24, 1601 and affected most of the North Sea and Baltic countries.

Underneath the caged lion is an image of a populated coastline and a cartographic symbol for the wind which is blowing towards the city. Just to make sure the viewer understands exactly what is going on, Saenredam has included people running for their lives, wheels underneath the city and the words ‘terra motus’—it’s an earthquake! There are reports of two earthquakes occurring in the North Sea area around the time this image was in production. One occurred on December 24th, 1601—the same date as the eclipse—and another reputedly occurred in February 1602. Researchers believe only one earthquake actually occurred or that the February quake was just a delayed aftershock. Others believe it’s just inaccurate reports of the incident made in 1690. If the December 24th earthquake coincided with an eclipse, it’s easy to imagine the long lasting effect an incident of that magnitude would have on Dutch memory.

Of all of the images of 17th century whale strandings that exist, Saenredam’s is certainly the most elaborate and surpasses all similarly-themed prints in terms of the sheer spectacle the engraving reflects. As the situation in the Netherlands stabilized and the Dutch Republic’s world standing seemed more secure and as the whale became viewed more as a commodity than a harbinger of doom, the production of this sort of image decreased. By the 18th and 19th centuries, the production of views of whale strandings had shifted to a purely documentary view of a rare and interesting event (see https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/jun/04/restoration-hidden-whale-dutch-painting for a cool story about a painting showing a beached whale).