It has been too long since we’ve given an update on the conservation of Monitor’s port gun carriage. So long in fact, that the conservation of its 250-ish components are now complete!!!

Looking back and reflecting on the many steps of this (large) object’s treatment, I really love that it has benefited from all of the research and discoveries done in the lab over the past 10 years. It is, after all, the largest Monitor object completed thus far and we were experimenting a lot along the way to provide the best treatment possible with current knowledge. We also knew that the work would benefit not only “our little Monitor” but the field at large. And we learned so much!

In terms of conservation, the complexity of this artifact was multifaceted:

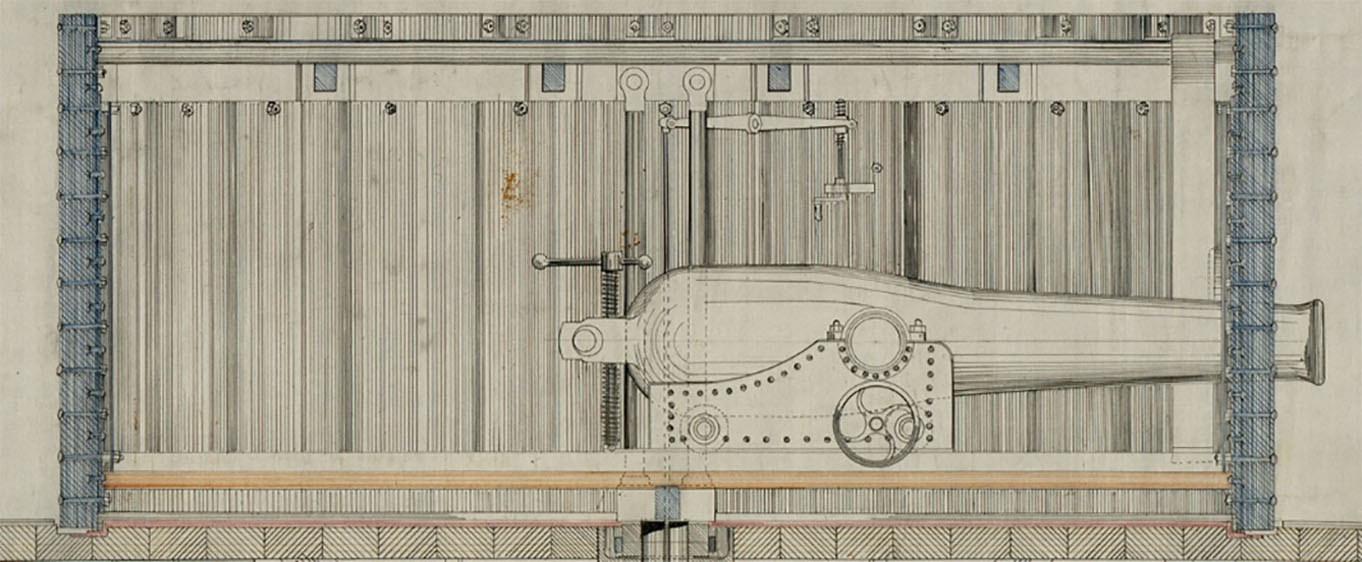

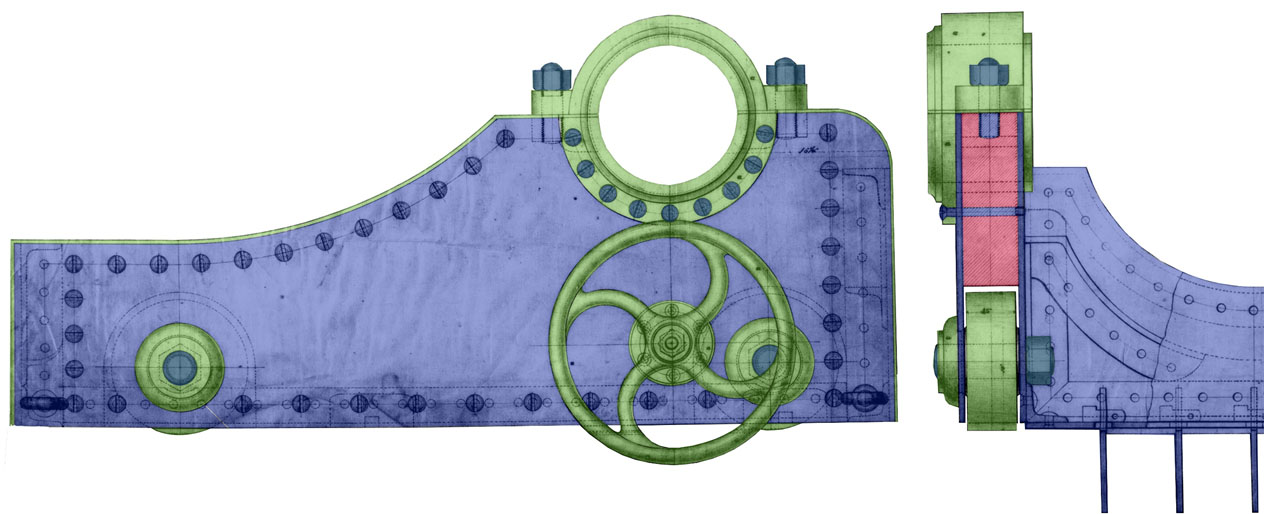

- It is made of 3 different materials (iron, copper alloy and wood), all requiring different types of treatment.

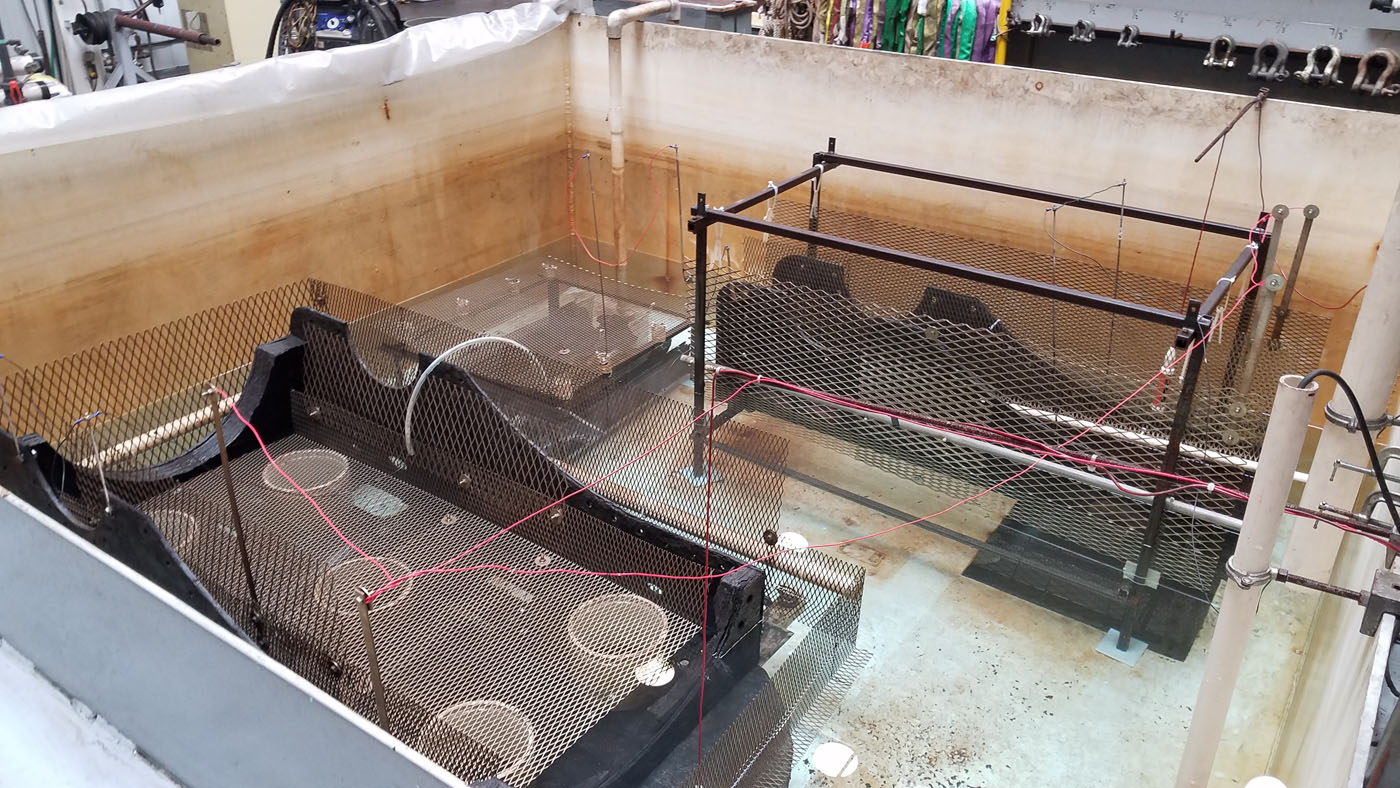

- Like all USS Monitor artifacts, having spent almost 150 years at the bottom of the ocean, the carriage needed to be desalinated. Since ocean salts had many years to enter the materials, reversing the process was a slow procedure. Failing to do so could lead to the formation of detrimental corrosion in the future.

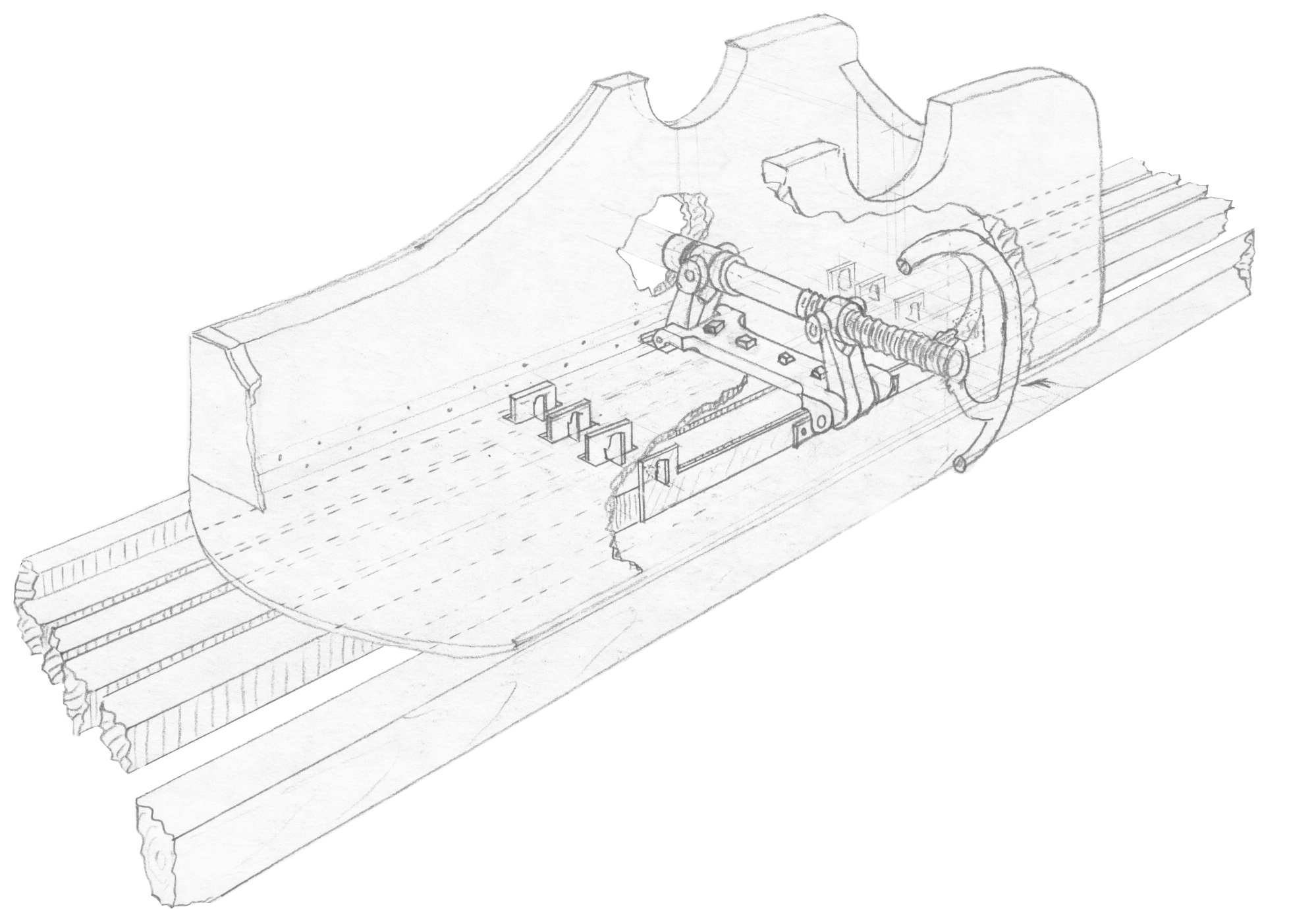

- In order to address the first two points, we wanted to fully disassemble the carriage. This would enable us to provide the most ideal conservation treatment for different materials and expose more metal surfaces for better desalination.

- However, full disassembly proved impossible due to 2 sets of white oak planking which are held together by large iron rivets that could not be taken apart. As a result, this made them wooden/iron composite objects of their own. Research and extensive testing had to be set to find an appropriate treatment to conserve these two materials together… which intrinsically require opposite types of care.

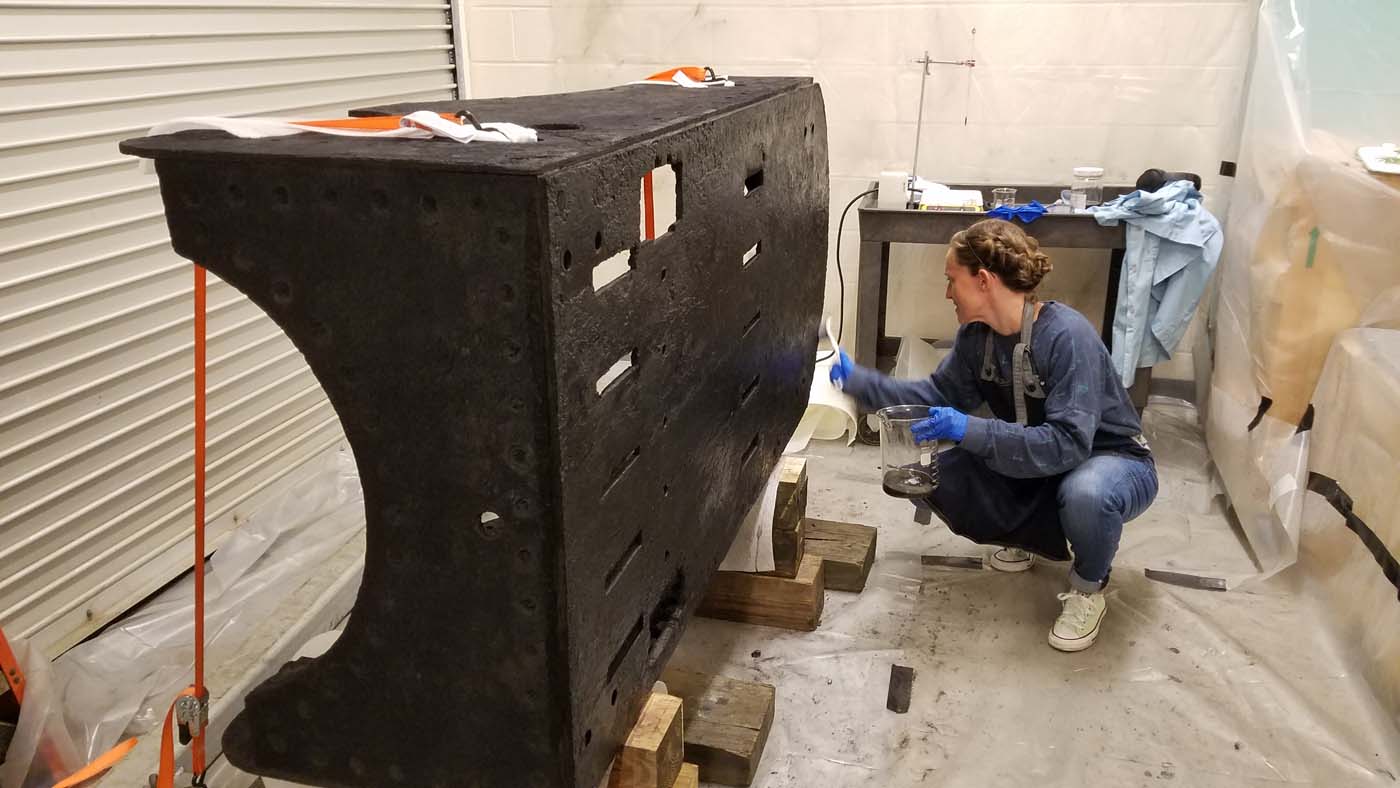

- And last but not least, the carriage is approximately the size of a compact car and weighs about a ton (literally!). Working on the object required draining its tank, rinsing it, using the overhead crane to lift the object, and then moving it back and refilling the tank at the end of the day (not something you start on a Friday afternoon!).

While it took approximately 2 staff members about a year to take the object apart as far as ethically possible (without damaging it), the metallic parts were in desalination for approximately 8 years afterwards (told you it was slow!).

Meanwhile in the lab, Will was having great success testing dry ice blasting to clean wrought iron surfaces. And, experience showed that the metal needed 3 passes of dry ice to be appropriately cleaned. Between each pass, artifacts were returned to desalination, where due to being cleaner, salts could be extracted more readily.

As a result, even after having already spent 5 years in a desalination bath, we decided to perform dry ice blasting on the main frame of the carriage and associated components, once a year, for the last 3 years of desalination treatment. Wrought iron has a unique way of corroding with pockets of impurities degrading first which make a perfect home for salts to accumulate. Cleaning the objects as thoroughly as possible is in their best interest!

At this time too, Laurie found the right parameters for us to clean copper alloys with dry ice. This allowed us to use this technique to complete the treatments of the copper alloy parts.

In the meantime, an appropriate solution was found to treat our wood/iron composites by adding a corrosion inhibitor to the bulking bath of the wood. Now the reason why we need to bulk the waterlogged wood is because its shape is mostly maintained by water molecules since the wooden cells are degraded. So if we dry, i.e. remove the water molecule from the wood, it will shrink and twist. And the reason why we had to add a corrosion inhibitor to the bath is because this bulking solution has a pH too low for iron, which would corrode if not protected. In any event… eventually, we had what we needed! Kate and I even pushed the study to make sure this corrosion inhibitor was not harmful to the wood (no discoloration or added degradation, click here if you would like to know more).

So after many years of cleaning, disassembling, successes and step backs, 2019 felt like time flew by as we dried the wooden/iron sides and the main iron components. The latter were also coated for added protection from environmental variations and they look phenomenal! We were recently in the process of prepping crates for storage of the many parts until an exhibit plan can be implemented and will get back to it as soon as possible.

It has been an adventure and we are well armed now to tackle the second gun carriage as well as many other Monitor assemblies.

Stay home and healthy everyone! We’re looking forward to seeing you all again once this storm has passed.