FAE: Forensic Art Examiner. Or maybe a “graphics imaging reprographic specialist” would be more appropriate? I need help as I’m slowly being driven crazy by a little graphite drawing with india wash by the Willem Van de Veldes (both the older and the younger).

This beautiful little artwork was acquired by the Museum in 1945 with a collection of 285 artworks on paper and prints accumulated by New York collector Pauline Riggs Noyes. It came to my attention after the Museum’s patron group, the Bronze Door Society, awarded the collections department $31,000 to buy some new cabinetry to store our artworks on paper. It intrigued me because it is one of the oldest drawings in the collection, it was simply cataloged as “men-of-war in a calm” when obviously there is something more interesting going on, and because it’s a freaking Van de Velde!!!! The father and son drawing and painting duo who many feel are the two most important maritime artists of the 17th century–if not EVERY century.

By the time the Museum was founded in 1930 the number of Van de Velde’s on the market was small and their prices were high so even if our buyers had found one they probably didn’t have the budget to acquire it. The purchase of the Noyes collection added three Van de Velde’s to our collection–although not one of the elder’s glorious pen paintings nor one of the younger’s beautiful oil paintings (????sad, pouty face aimed at all you collectors out there–can you help us fill this glaring gap in our maritime art collection?)

Like many pieces in our collection this little wash drawing has never been the subject of any sort of serious study. Unlike the other images, in 1973 curator John Sands asked the world’s foremost expert on the Van de Veldes, Michael S. Robinson, keeper of pictures at the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich from 1947 to 1970, to examine the piece and provide his thoughts–which then sat in the object file for 46 years with no one paying them any mind. I decided to use his comments as a springboard from which to launch my own investigation–and it’s caused me several months of intense frustration!

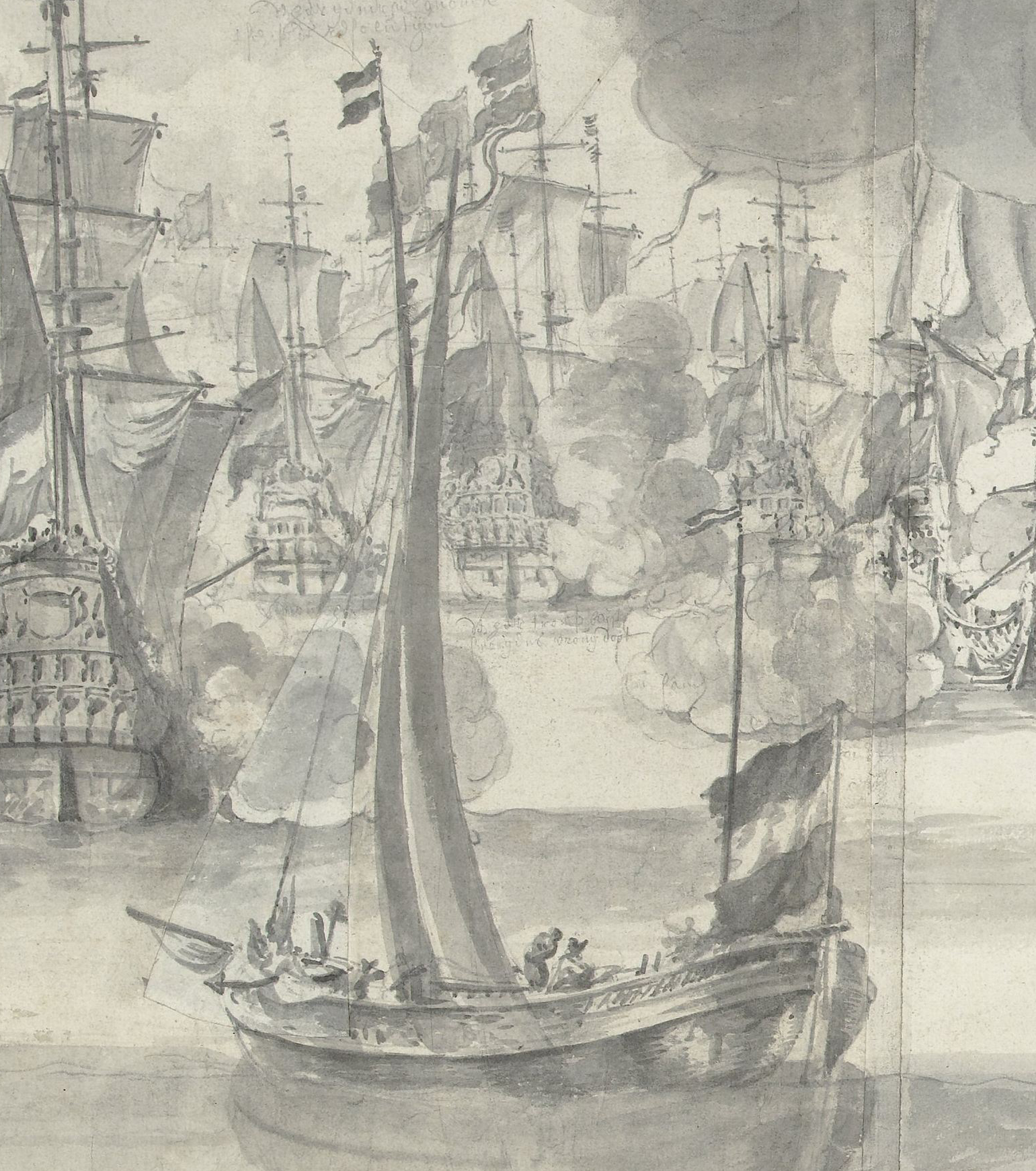

In his comments Michael Robinson stated that as the long handwritten inscription in the top left corner indicates the drawing shows a council of war in the Dutch fleet. Wait a minute. I didn’t notice an inscription did you? Well, if you look really hard it’s there. Sadly most of the text is too faint to read. What is legible is in Dutch so even when I can see the words (or parts of them) I still don’t understand them. Mr. Robinson was able to read just two words: Krÿgsraet houdende, which was just enough to determine that the scene shows a council of war.

Robinson commented that Admiral Michiel De Ruyter held a council of war before the Four Days battle in June 1666. Since none of the ships is flying the flag and pendant of De Ruyter’s flagship Zeven Provincien that seems to rule out this event. To make doubly sure I studied a large pen painting by Van de Velde the Elder of De Ruyter’s 1666 war council and clearly the ship holding the council in our artwork is not the Zeven Provincien.

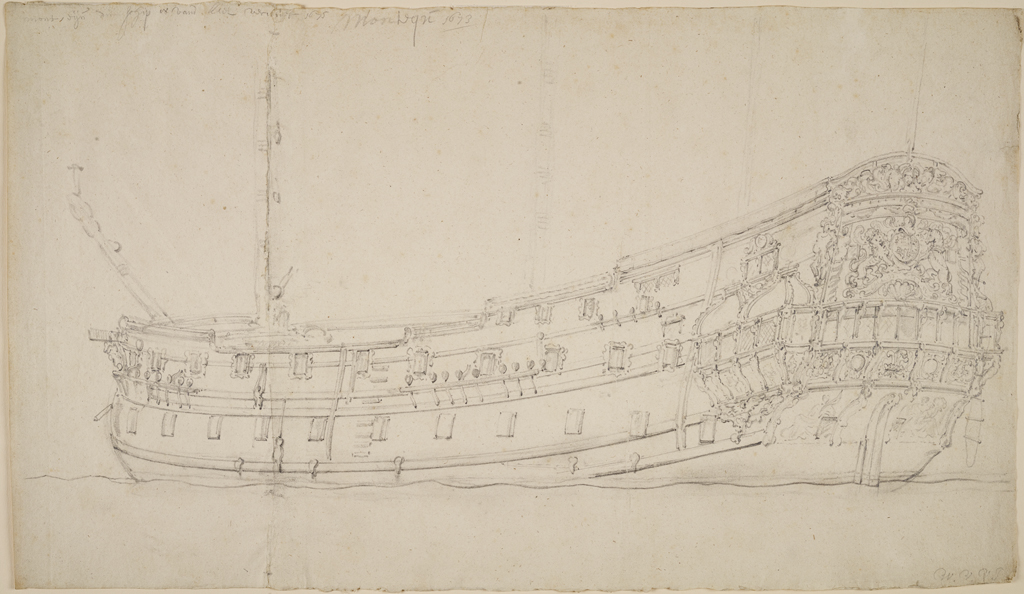

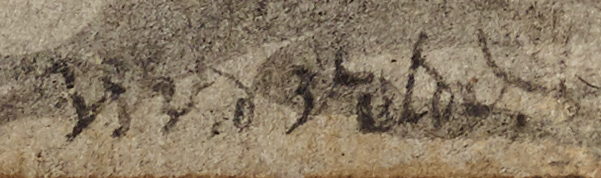

Robinson also indicated that the ship on the right is the Ster (also known as the Gouden Ster)– super obvious thanks to the large six-pointed star on her taffrail. He also stated that the ship at the left flying a flag on the main mast and a pendant on the foremast is a Zeeland ship that’s carrying an admiral of the van squadron. Robinson’s only other comments were that the ships in the background at the left were probably the original work of the Elder, but that the rest of the drawing has obviously been “worked up” with wash applied by another hand. At the time he didn’t believe the signature at the lower left was either the Elders or the Youngers but most experts now recognize it as an early signature of Van de Velde the Younger.

From this point I was on my own. My first task was to try and use today’s advanced technology to make the inscription more legible. Experimenting with various forms of lighting (raking, backlit, straight down, etc.), magnification with loupes and a microscope, and infrared photography (courtesy of conservator Paige Schmidt) revealed some of the text, but in the end, the most useful tool proved to be high resolution digital photographs manipulated in Photoshop. With a little more of the text legible I sent the images to a friend in the Netherlands to see if he could interpret the inscription. He wasn’t willing to take a crack at it but he sent the images to former colleague, Dr. Remmelt Daalder, who was. While I waited for a response, I focused my attention on interpreting the scene itself.

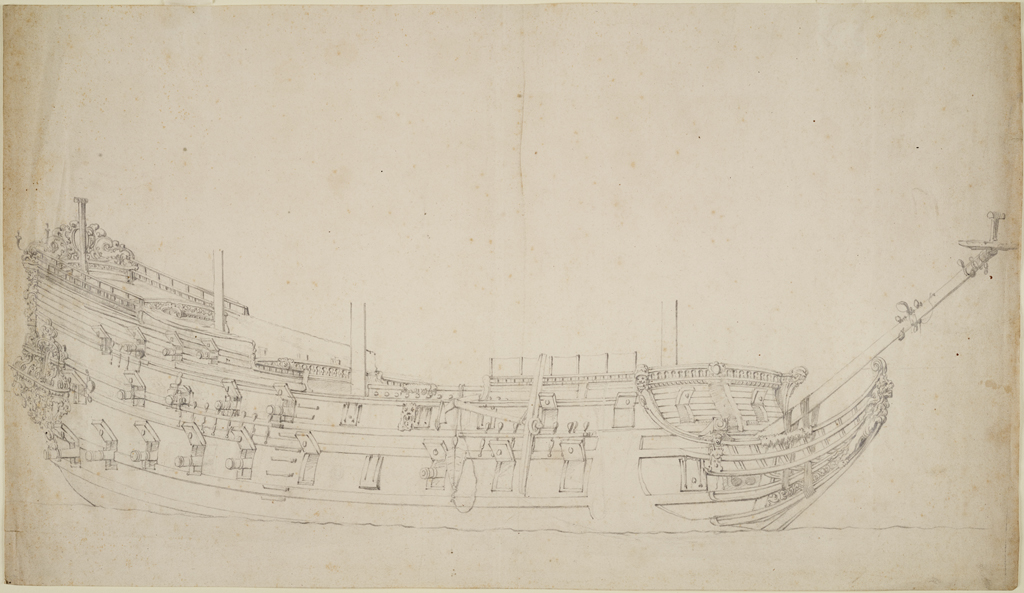

One of the nice things about Dutch ships in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is that they are easily identified by the decoration on their taffrails (that fancy decorative bit on the back of the ship). Since I could see the taffrails of three ships fairly well and Mr. Robinson had already supplied the identification of Ster I figured that was the best place to start–knowing what ships were depicted might help identify the event.

Maritime art was “invented” in the Netherlands in the 16th century. By the 17th century there was a burgeoning trade in the “marine,” as it was called, so there is a lot of imagery available to help identify individual ships. One of the most prolific studios of the time belonged to the Van de Veldes.

Willem Van de Velde the Elder worked as a deckhand on his father’s barge and served on a warship. By the end of the 1630s he was trading as a “ship’s draughtsman” and was supplying drawings to engravers for prints. Around 1640 Van de Velde developed his unique art form of pen painting, also called a penschilderij, a durable form of drawing that wouldn’t deteriorate with long term exposure to light or moisture. By the 1650s Van de Velde had developed such a reputation as an artist that he was employed by the admiralties of the Republic of the United Netherlands to document naval actions involving the Dutch fleet. Starting with the 1653 Battle of Scheveningen (also called the Battle of Ter Heijde) Van de Velde sailed with the fleet at least six times. Besides documenting the fleet’s activities he also delivered official correspondence and provided written reports of the actions. Willem Van de Velde the Younger followed directly in his father’s footsteps although his preferred art form was the oil painting.

Amazingly, the very first book I cracked open (The Willem van de Velde drawings in the Boymans-van Beuningen Museum, Rotterdam) provided the identification of the ship holding the council of war as well as a possible attribution for the scene.

As I mentioned earlier, the first naval action Van de Velde documented was the August 1653 Battle of Scheveningen, the final action of the First Anglo-Dutch war. After his defeat at the June 12-13, 1653 Battle of Gabbard Vice Admiral Maarten Harpertszoon Tromp withdrew his fleet to the roads off Flushing to refit. Other parts of the Dutch fleet lay in the roads off Goeree and Texel so while Tromp repaired the main fleet, Vice Admiral Witte de With was given the task of assembling a secondary squadron in the Texel roads. Van de Velde joined this smaller squadron while it was still anchored near Den Helder in early August.

Van de Velde immediately began documenting the squadron’s activities and the very first image drawn showed Commodore Evert Marre in Hollandia flying the signal for a council of war. Unfortunately the quality of the image in the book is fairly poor so the vessel’s taffrail is fairly indistinct. Luckily, just a few pages later another image provided a slightly clearer view of Hollandia’s taffrail and it looks suspiciously similar to the vessel holding the council of war in our artwork. My theory that our ship is Hollandia was reinforced by another Van de Velde drawing at the Boijmans-van Beuningen Museum as well as a Van de Velde pen painting in the Rijksmuseum. [Note the similar taffrail decoration of a rampant lion on a round/oval shield in each of the images.]

Working on the assumption that our image depicts the ships of Witte de With’s squadron anchored off Den Helder I tentatively identified the third ship–thanks to Mr. Robinson’s identification of the vessel as a Zeeland ship with an Admiral on board–as the Indiaman Vlissingen. This ship was purchased by the Admiralty of Zeeland for use as a warship in 1653. According to ‘Dutch Warships in the Age of Sail 1600-1714’ the 50-gun Zeeland ship named Vlissingen had Vice Admiral Johan Evertsen on board during the Battle of Scheveningen. This final attribution left just two ships unidentified and since I couldn’t see any details of their taffrails I figured I was pretty much out of luck–and then an email arrived from the Netherlands.

Unfortunately, while Dr. Daalder was able to read more of the inscription than Michael Robinson knowing the additional words didn’t provide any help with identifying or dating the scene. What Dr. Daalder did notice, however, was a faint pencil inscription beneath the hull of the ship at the far left: de Vreede. The Vrede was a 44-gun ship built in 1650 by the Admiralty of Amsterdam.

With four of the five major ships identified, I felt fairly confident that I could provide a tentative attribution for the scene. And then I stumbled across a small artwork in the collection of the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich that was so similar to our image in size and style it pretty much sealed the deal.

Robinson’s description of the artwork at the National Maritime Museum provides a description that’s fairly consistent with the image at Mariners: “the pencil work of this drawing may have been done at sea, but the heavy black wash was added later…The inscriptions are certainly by the Elder, but the signature may well be a genuine early signature of the Younger, which suggests that he may have put on the wash.”

So, even after spending many, many, many hours agonizing over the inability to read the inscription I feel fairly confident the scene shows a council of war held by Commodore Evert Marre and/or Vice Admiral Witt de With as the Dutch fleet lay off the entrances of the Texel around August 7, 1653. I do hold out hope that someone with some sort of super technology will crawl out of the woodwork and magically make the inscription legible. With luck, it will confirm my research is sound and my tentative attribution is correct.

P.S.: If any of you Photoshop gurus want to try your hand at making the inscription more legible check out this article by the Smithsonian Institution Archives: https://siarchives.si.edu/what-we-do/forums/collections-care-guidelines-resources/help-making-documents-more-legible

If you shoot me a message I’ll send you a TIFF file to play with!