In recent months, I’ve learned two amazing tales of deception and daring that thrilled me to no end. Although the events occurred almost two centuries apart (the first in the late 17th century and the second during the American Civil War) the men involved were that rare breed of human male that inspires fictional characters like Jack Aubrey, Horatio Hornblower or my all time favorite Lord Nicholas Ramage (I actually had to remind myself to BREATHE while reading this series!). Since we could all use some excitement in our new stay-at-home-where-nothing-interesting-ever-occurs lives, I thought I would pass them along.

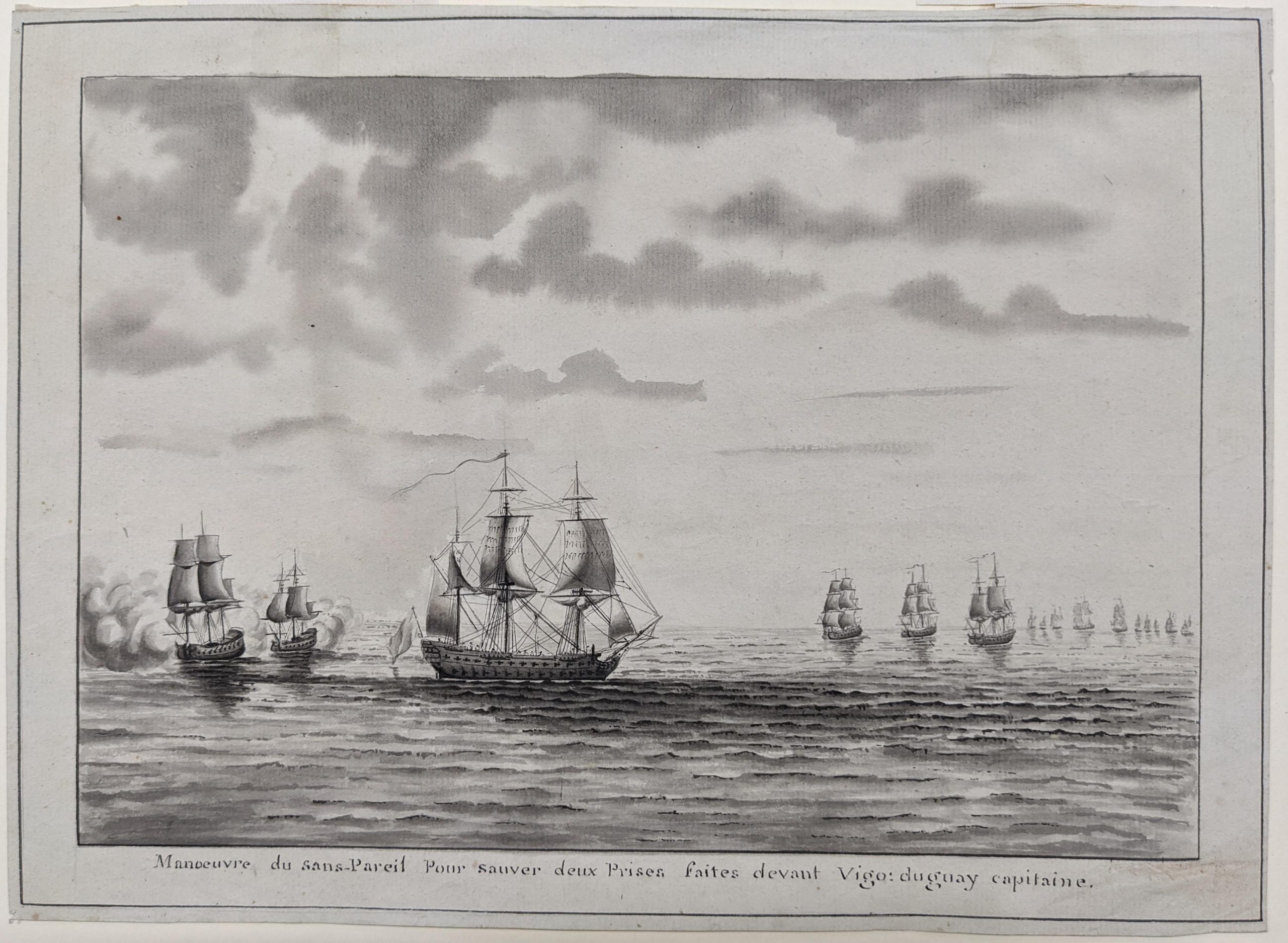

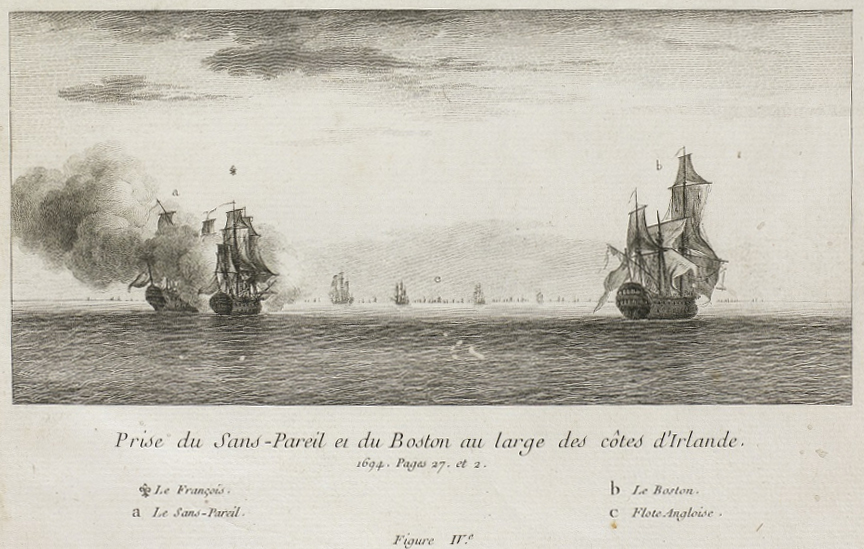

I stumbled across the first story while working on our watercolor rehousing project. The image is a small india wash drawing by Nicolas Marie Ozanne titled Manoeuvre du Sans-Pareil pour sauver deux prises faits devant Vigo [Maneuver of Sans-Pareil to save two prizes taken before Vigo]. The artwork was engraved by Jeanne Francoise Ozanne and published by Yves Marie Le Gouaz in ‘Recueil des combats de Duguay-Trouin’ which is where I learned the story behind the image.

It all starts during the Nine Years’ War (1688-1697) on January 15, 1695 when René Duguay-Trouin, a daring and wildly successful French privateer, captures the 42-gun English fourth-rate ship Nonsuch off the Isles of Scilly. The ship is taken into the French service as the privateer Sans Pareil and Duguay-Trouin is made her captain.

While sailing off the coast of Spain in July of the following year Duguay-Trouin learns from several French fishermen that three Dutch merchant ships loaded with large masts and other merchandise are anchored in Vigo harbor. The merchantmen are waiting for an English warship from Coruña that will escort their little convoy to Lisbon. Duguay-Trouin decides to try and use Sans Pareil’s English construction to his advantage and trick the Dutchmen into leaving port. [Could merchant sailors in the 17th century really tell what country a warship was constructed in just by looking at it? Might be a good topic for a future blog post!]

On a beautiful, calm morning the Sans Pareil appears at the entrance of Vigo harbor. The ship is flying English flags and pennants from every mast, the ship’s main courses are brailed up to the yards and its topsails are “hanging loose and flying” to give the appearance of a consort leisurely waiting for its charges to leave port.

Two of the Dutchmen immediately begin setting sail to join their “English” escort. The third vessel tries to do the same but finds herself in a position that prevents the crew from weighing anchor. Once the ships are clear of the port’s protecting guns Sans Pareil hoists her French colors and leisurely places prize crews aboard the merchantmen who really didn’t have any choice but to shake their heads and surrender. Duguay-Trouin then steers his little fleet for the closest French port.

Early the following morning Duguay-Trouin finds himself several miles downwind from a large English fleet. He orders the prize crews to fly the Dutch flag and salute the Sans Pareil with cannon fire, before sailing downwind to make it appear as though the Sans Pareil was simply an English ship rounding up his charges to join the English fleet. He then sails towards the English fleet with “as much assurance and tranquility as I could have done if I had been a real one of their own” all the while praying that his maneuvers with the two prize ships and Sans Pareil’s English construction would fool the British.

Upon seeing the three vessels on the horizon the British commander detaches two large vessels and a 36-gun frigate to investigate the newcomers. The two larger vessels are deceived by Sans Pareil’s appearance and non-hurried actions and begin sailing back to the fleet. The frigate captain, however, persists in wanting to speak to the crew aboard the two prizes. Duguay-Trouin must have been worried the frigate would discover his ruse because he carefully, but calmly maneuvers his ship between the two prizes and the frigate.

Remaining distrustful, the captain of the frigate keeps his crew on alert and sends a ship’s boat to speak with the Sans Pareil. Halfway there, the British crew recognize the ship is actually French and turn around to warn the frigate. Realizing his ruse has been discovered Duguay-Trouin lowers the British flag, hoists the French flag and fires a broadside. The frigate responds in kind but is unable to withstand the firepower of the larger Sans Pareil. The two larger British vessels immediately sail to the frigate’s aid so Duguay-Trouin sensibly quits the fight.

Alerted to the frigate’s sinking condition the two larger vessels end their pursuit and sail to her aid picking up the ship’s boat that had been trapped between the two battling vessels on the way (I bet the sailors in that little boat needed to change their pants when they got back to the ship!). All of this activity and oncoming darkness enables Duguay-Trouin to hustle her two prizes away to the safety of Port-Louis.

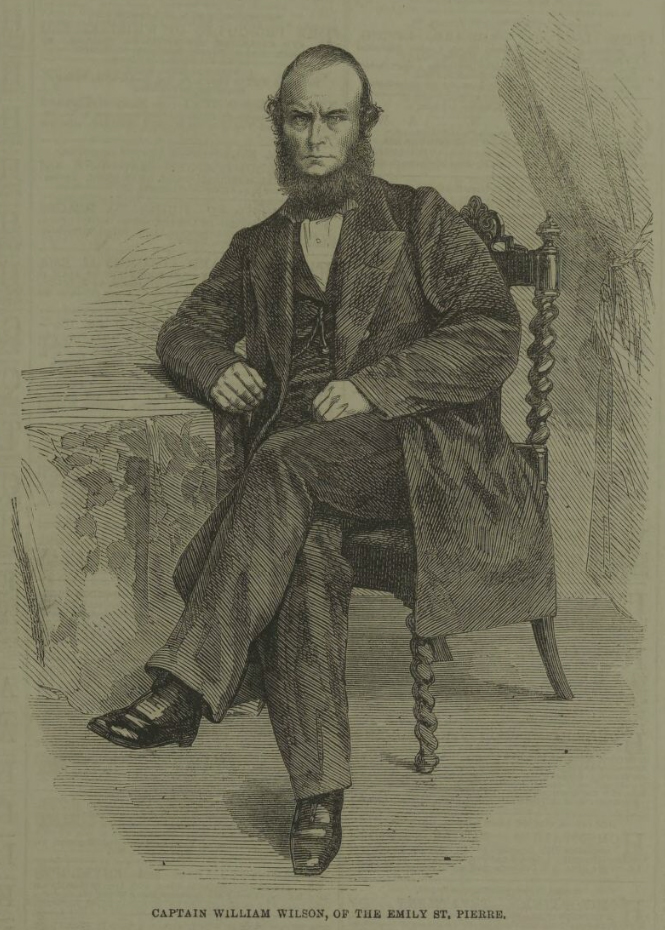

As I mentioned earlier, the second story occurs during the American Civil War. It starts with a February 7, 1862 letter from Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles to the flag officers of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. In the letter he reports that the three-masted, square rigged, British owned ship Emilie St. Pierre (884 tons) had cleared Calcutta on November 27, 1861 and was headed for St. John, New Brunswick. Although her manifest indicated she was headed to Canada, the ship had run the blockade in 1861 and Welles felt her true destination was one of the blockaded southern ports.

Emilie St. Pierre, captained by William Wilson, was owned by Fraser, Trenholm and Company, a British company with heavy ties to the south and a fleet of ships that regularly ran the blockade. The company’s orders to Wilson were a little looser than those written on the manifest. Wilson was to take the Emilie St. Pierre to Charleston and ascertain whether a blockade of the port remained in place. If not, he was to take on a pilot and enter the port. If the port was blockaded, he was to proceed to St. John, New Brunswick. As Wilson felt he wasn’t carrying anything construed as contraband (2,173 bales of gunny bags for baling cotton) and he was only off the coast to “determine if a blockade was in place” (yeah…right…) he apparently didn’t feel threatened by the possibility of seizure.

On March 18, 1862 while still twelve miles off the port of Charleston The Emilie St. Pierre was confronted by the Federal warship James Adger. Wilson hauled up the courses and backed the main yard and was boarded by two boats. The boarding sailors took possession of the vessel and sailed it to the blockading fleet. Captain Wilson was taken on board the USS Florida and told by flag officer J. R. Goldsborough that because there was a small quantity of saltpetre on board, the ship was being seized as a “lawful prize of the Federal Government.”

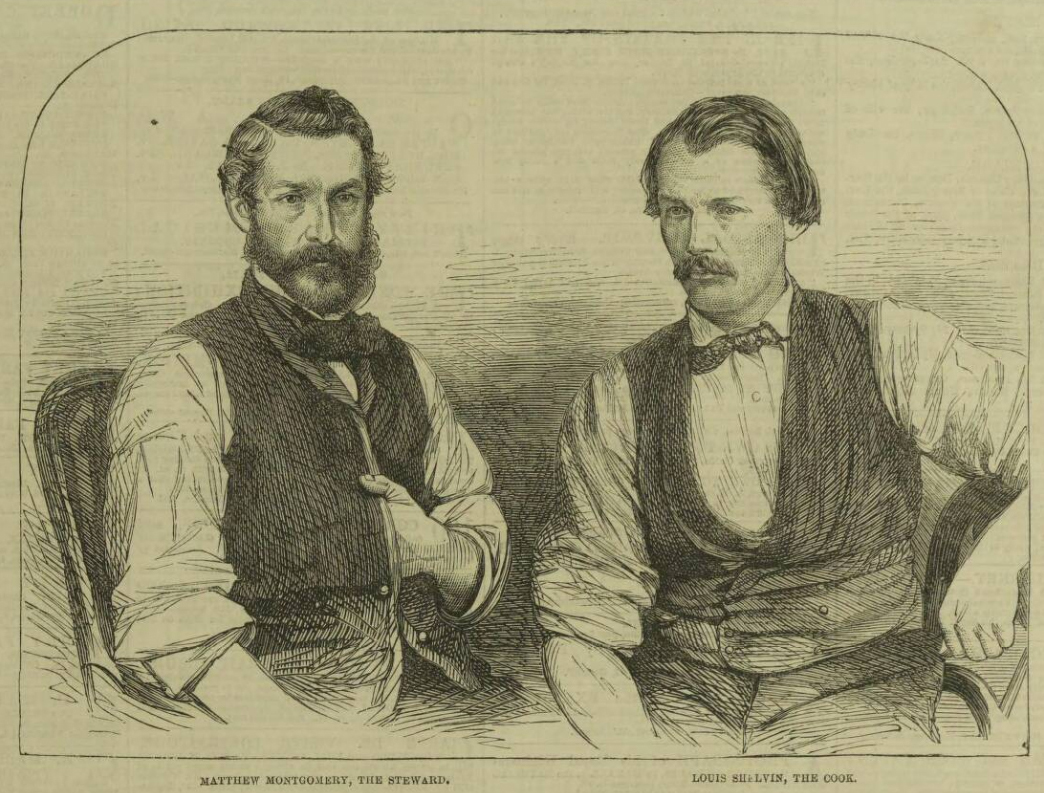

When told the ship was being sent to Philadelphia Wilson arranged to travel as a passenger on the vessel so he might argue for the ship’s release once they reached port. Upon returning to Emilie St. Pierre Wilson found a prize crew consisting of Acting Master Lieutenant Josiah Stone and First Assistant Engineer John S. Smith, both of the USS Florida, acting master’s mate Hornsby of the USS Onward and ten men in charge of the vessel. Only two of the Emilie St. Pierre’s original crew remained aboard, steward Matthew Montgomery and cook Louis Schelvin.

Around 4:00 AM on March 21st Wilson woke Montgomery and Schelvin and recruited their assistance in a desperate plan to retake the ship. Their first two victims were the acting master’s mate Hornsby and first assistant engineer John S. Smith who were asleep in cabins in the after part of the ship. The three conspirators carefully relieved both men of their weapons before gagging them, clapping them in irons and locking them in their cabins to prevent them from raising an alarm.

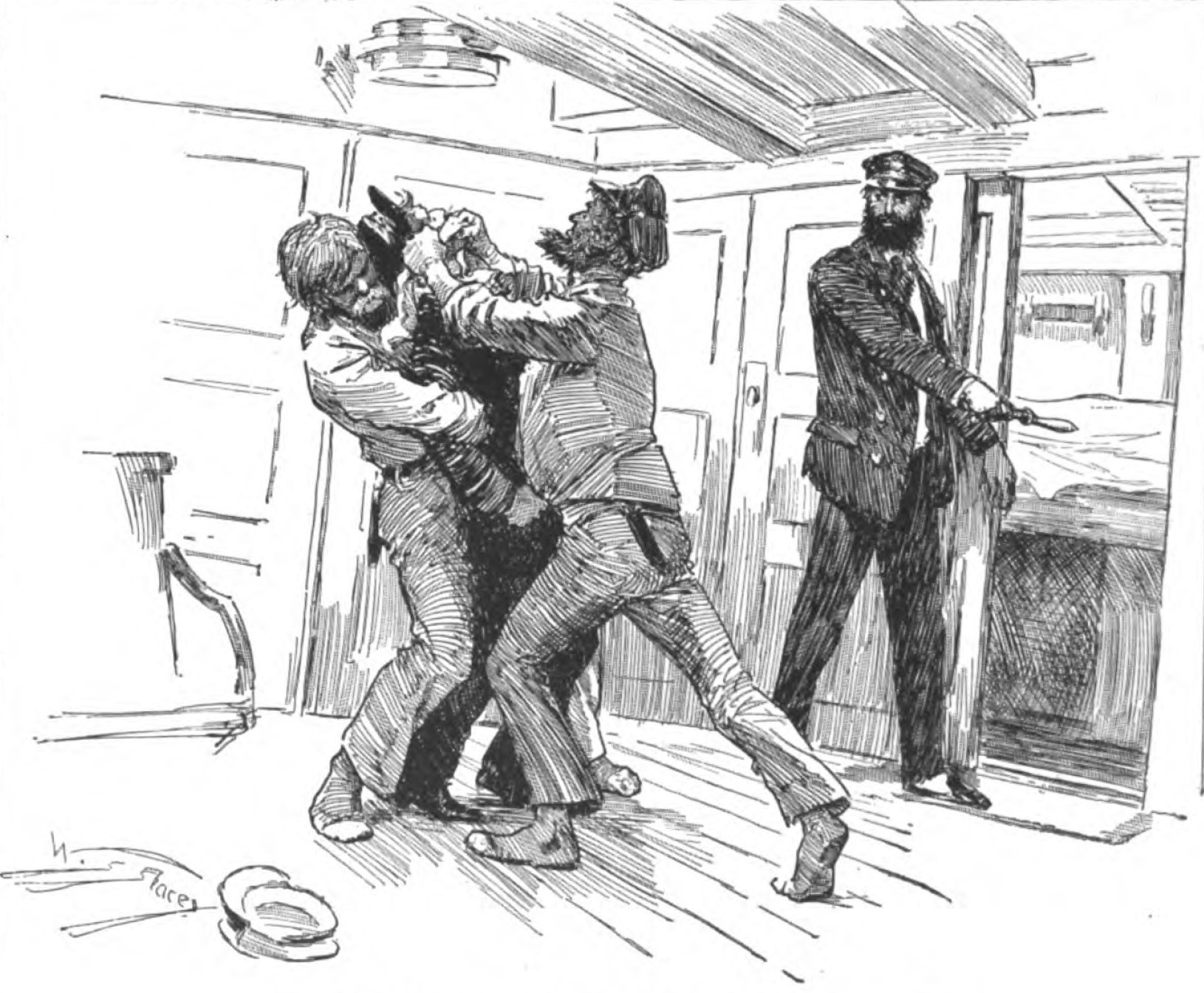

Captain Wilson then, ever so coolly, headed for the deck where he spent a casual ten minutes walking the deck with Lt. Stone discussing the weather and the ship’s position. After casually questioning Lt. Stone’s navigation around Cape Hatteras, Captain Wilson invited the unsuspecting lieutenant into his cabin to mark the vessel’s position on the chart and have a cup of coffee. Upon entering the cabin Wilson, armed with an iron belaying pin, informed Lt. Stone that under no circumstances was Emilie St. Pierre sailing to Philadelphia while Montgomery and Schelvin tackled, gagged, tied up the hapless lieutenant, tossed him headfirst into a berth and locked him in.

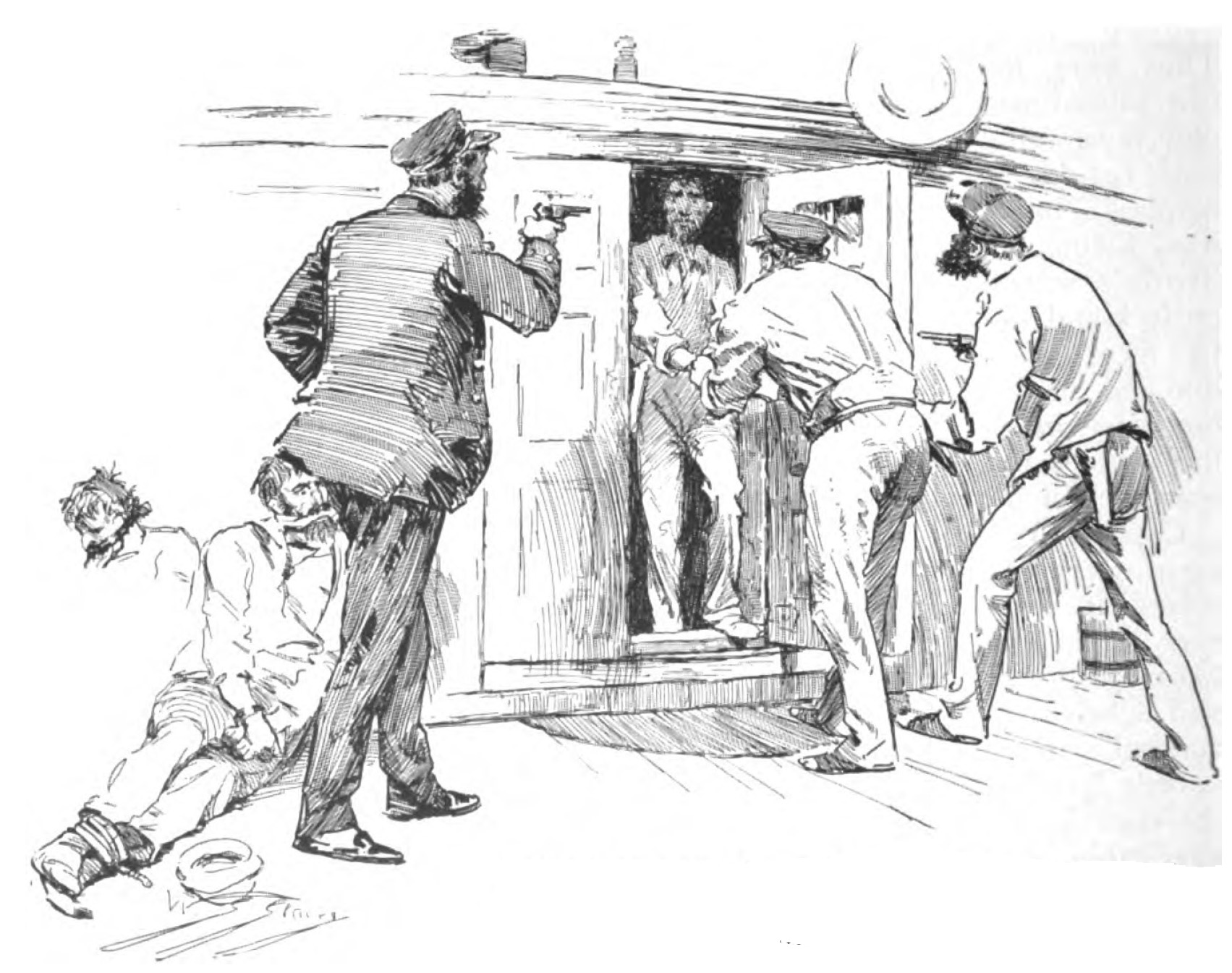

With the three officers secured, Wilson returned to the deck to deal with the five men standing watch on deck. At the same time the cook and steward secured the last remaining members of the still unsuspecting prize crew by sealing the door to the fo’c’sle. Wilson quickly formed a plan to entrap three members of the prize crew by pretending to pass on orders from Lt. Stone regarding the retrieval of a coil of rope from a nearby scuttle. Suspecting nothing, the three men entered the scuttle and quickly found themselves trapped by a hatch sealed over the only way in and out. Wilson then spun around and aimed a captured pistol at the helmsman and told the man to remain quiet or suffer the consequences. Calling aft the last remaining member of the prize crew (he had been standing lookout on the bow) Wilson asked the man if he would assist with sailing Emilie St. Pierre back to England. When he declined the man was unceremoniously bound and gagged and chucked into the scuttle with the other trapped men.

At this point Wilson had to deal with the remaining members of the crew– those trapped in the fo’c’sle– who, it appears, still remained blissfully unaware of what had taken place. Unlocking the door, Wilson called to the watch below and as each man came on deck they were seized by Montgomery and Schelvin. The first two men were captured without incident but the third saw what was happening, cried out, pulled a knife and rushed towards Montgomery giving the steward no choice but to shoot him. This was the only shot fired during the takeover and luckily the bullet passed cleanly through the man’s shoulder.

The remaining members of the prize crew were allowed to come on deck one at a time and were questioned by Captain Wilson about their willingness to help take the ship to England. Two men volunteered but were “landsmen” which meant their sailing skills were pretty limited. A few days later two more men volunteered, but one of them (one of the few qualified sailors on board) had apparently only volunteered to make an effort to retake the ship so he was quickly reconfined.

At this point, if you’ve been counting, you’ll note that Captain Wilson has just five men–none of whom are sailors–and himself to navigate the huge vessel across 3,000 miles of open ocean. Astoundingly Wilson succeeded but sadly exactly how he did it wasn’t recorded which isn’t exactly surprising considering how shorthanded they were. I don’t think I would have taken notes either if I was pretty much single-handedly sailing a ship like that across the ocean.

It took Wilson thirty days to get Emilie St. Pierre back to England and I have no clue how he did it. I guess he was lucky in that all of the sails were set when the takeover occurred so all Wilson had to do was manage them–but that doesn’t mean it was an easy task. When a gale hit, Wilson passed the reef-tackles through the capstan so a single man could haul them and then turned the wheel over to Montgomery and Schelvin while he climbed aloft to tie reef points in the sails. Unfortunately that storm also carried away the tiller and the ship spent twelve hours pretty much uncontrollable until a jury-rigged rudder could be set up.

I’m obviously not the only person who was astounded by what Wilson accomplished. All of England applauded Wilson’s exploits. The Mercantile Merchant Association raised a subscription and presented Captain Wilson with “a magnificent service of plate” and a gold chronometer watch. Fraser, Trenholm and Company presented Wilson with 2000 pounds while the cook and steward each received purses of 20 pounds and silver medals commemorating their actions. Once the original crew of Emilie St. Pierre arrived in England they presented Wilson with a “splendid sextant.” That beautiful instrument now resides in the Museum’s collection where it will remain a testament to Wilson’s daring and courage.