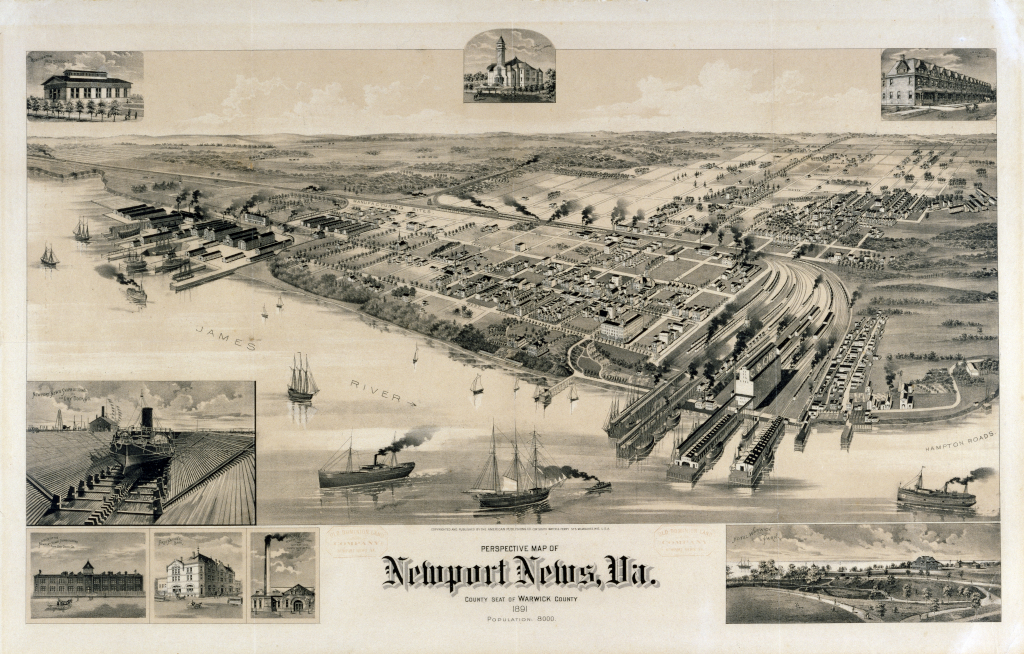

Although several sections of modern Newport News were visited when the English colonists first came to Virginia, Newport News remained just a place name on maps for more than 250 years. Yet, the Civil War brought attention to this point of land and 30 years later, the city of Newport News was born.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

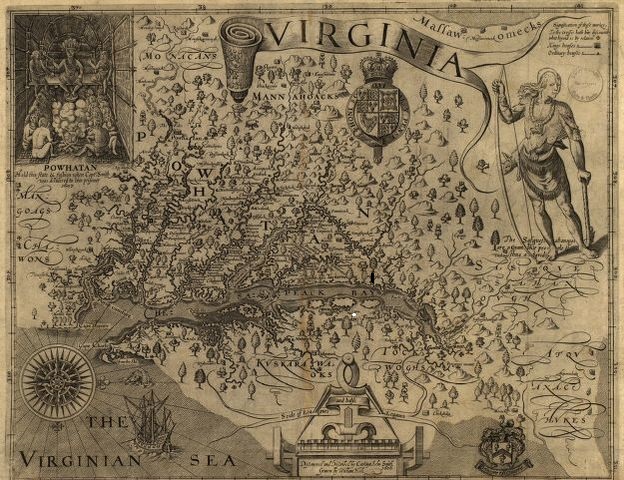

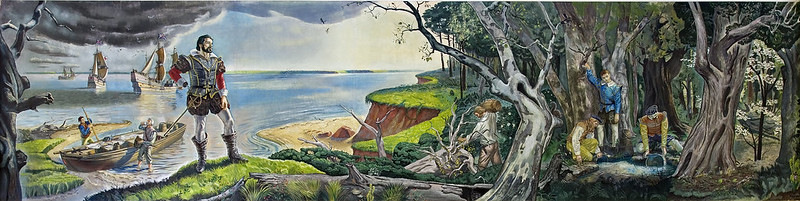

So, where did the unusual name of Newport News come from? The city’s downtown was labeled Point Hope on Captain John Smith’s map of Virginia. The first references to “Newportes Newes,” with eight different spellings, appears in the Virginia Company’s record of 1619, making it one of the oldest English place names in the New World.

It is clear that the name had been in common usage from the colony’s beginning. According to one popular version, when the colonists abandoned Jamestown in 1610, they ended their exodus when they learned of Lord De La Warr’s arrival with more settlers and food. It was Captain Christopher Newport, so the story goes, who delivered the news prompting their turnabout and the colony’s salvation. So, the place where that occurred is remembered as “Newport’s News,” which is how the name was usually printed until the city’s formal founding in 1896.

However, there are competing explanations, or folk etymologies, for the name origins. One holds that it was called “New Port Newce” after Captain Thomas Newce and Sir William Newce, who came to Virginia from Newcetown (also called Port Newce), Ireland, in 1620-1621. According to Hugh Blair Grigsby, this combination links the names of Newport and Newce.

Yet another theory comes from American writer Edward Everett Hale, author of the short story “The Man Without a Country,” first published in the Atlantic in December 1863. Hale suggested the name was a corruption of Newport Ness – “ness” being an Old English word for a headland or promontory.

Whatever the fabled or real truth may be, it seems impossible to say with absolute certainty just how Newport News got its name. But the most obvious reasoning would appear to credit the explorer, Captain Christopher Newport. He made five trips to Virginia when the colony was young, bringing, according to Captain John Smith, that most important cargo: news.

NEWPORT’S NEWS POINT

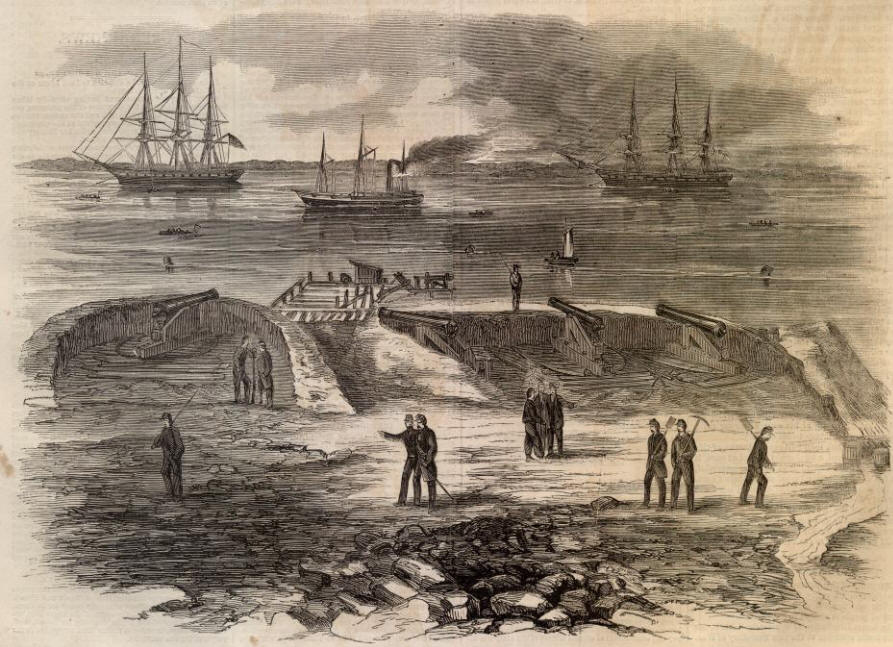

When the Civil War erupted, Newport’s News Point became a household name. On May 27, 1861, Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler built Camp Butler on the point where the James River empties into Hampton Roads. Camp Butler had a water battery and was reinforced by two Union warships, USS Congress and USS Cumberland.

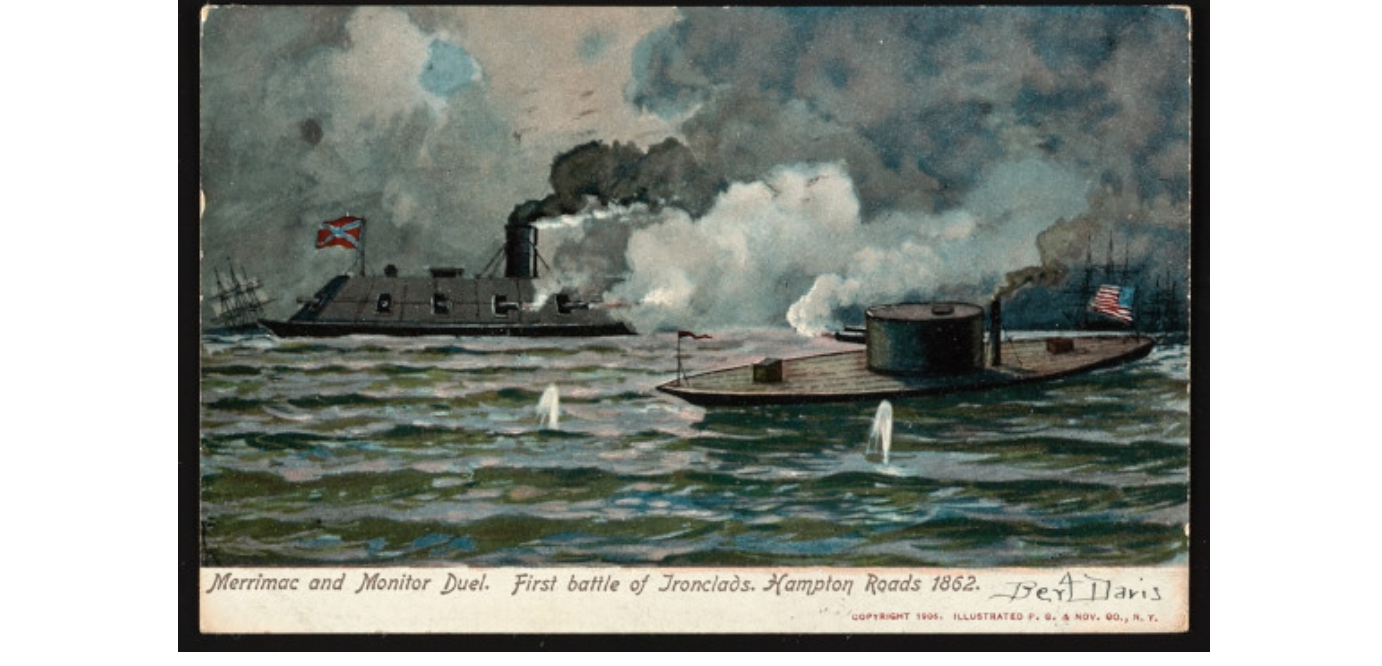

On March 8, 1862, Newport News became a household name when the Confederate ironclad ram, CSS Virginia (Merrimack), sank both of these powerful warships in one afternoon, proving the power of iron over wood. At the war’s end, the Newport News POW camp was established next to Camp Butler, holding Confederate soldiers. Newport News was now a place of importance. Yet, it was soon forgotten as the entire region of eastern Virginia strived to rebuild after the war.

A CITY IS BORN.

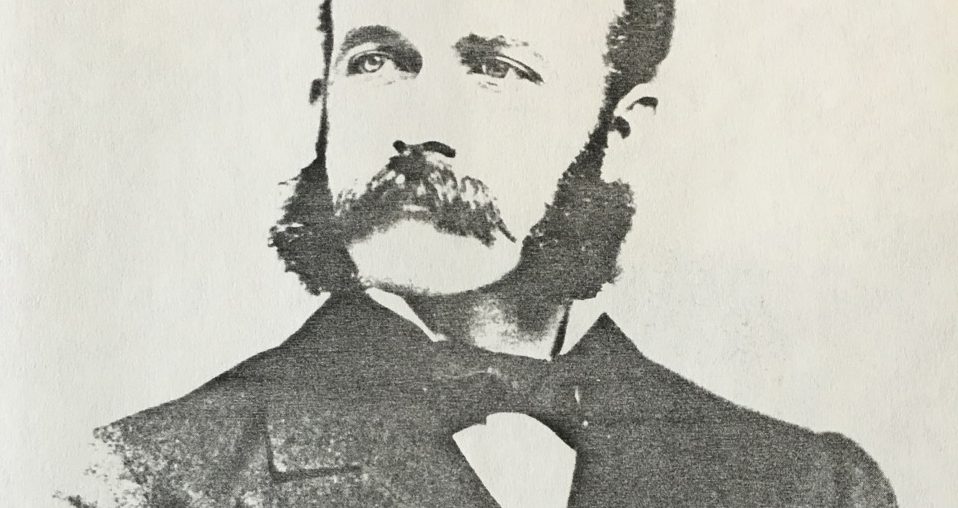

As a young man, Collis Potter Huntington traveled throughout the north and southeast coast as a Yankee peddler. His travels brought him, as the story goes, to Hampton Roads. While there he visited Newport’s News Point about 1839 or 1841. He later reflected, there is:

“a point so designed and adapted by nature that it will require comparatively little at the hand of man to fit our purposes. The roadstead, well known to all maritime circles, is large enough to float the ocean commerce ….it is never troubled by ice and there is enough depth of water to float any ship that sails the seas and at the same time is so sheltered that vessels can lie there in perfect safety at all times of the year.”

Huntington believed that there “could no better place for a city.” However, his fortunes blossomed when he was in California: he created the Central Pacific Railroad which became part of the Transcontinental Railroad, and the Southern Pacific Railroad. He then acquired the bankrupt Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad with the goal of connecting the Ohio River with the Atlantic Ocean.

Using the Old Dominion Land Company as a cover, Huntington began purchasing land at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula to bring his railroad to Newport News Point. He had other options like West Point or Yorktown; yet Huntington liked to control everything. So, he chose Newport News.

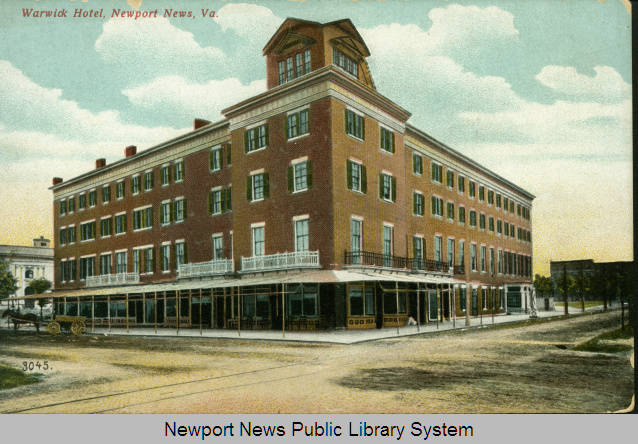

On December 6, 1880, Huntington endeavored to change the town’s name to “Minnetta” in honor of his adopted daughter. But local opposition blocked this name change, making this rebuff Huntington’s only defeat on the Peninsula. By 1881, the C & O reached the mouth of the James River to the new port city. Huntington owned and created everything — port facilities, land that was sold as lots for house construction, the Hotel Warwick and Casino Grounds, water supply, and gas and electric companies — everything.

Huntington knew that inter-city transportation was a necessity. Accordingly, the C & O established a ferry service to Norfolk and Col. Carter M. Braxton, who worked for Huntington building the railroad, established the Newport News Street Railway Company which later expanded into Hampton and Newport News Electric Car Company. The city began to prosper as workers and businessmen began moving to Newport News to partake in this economic growth.

THE CITY EXPANDS.

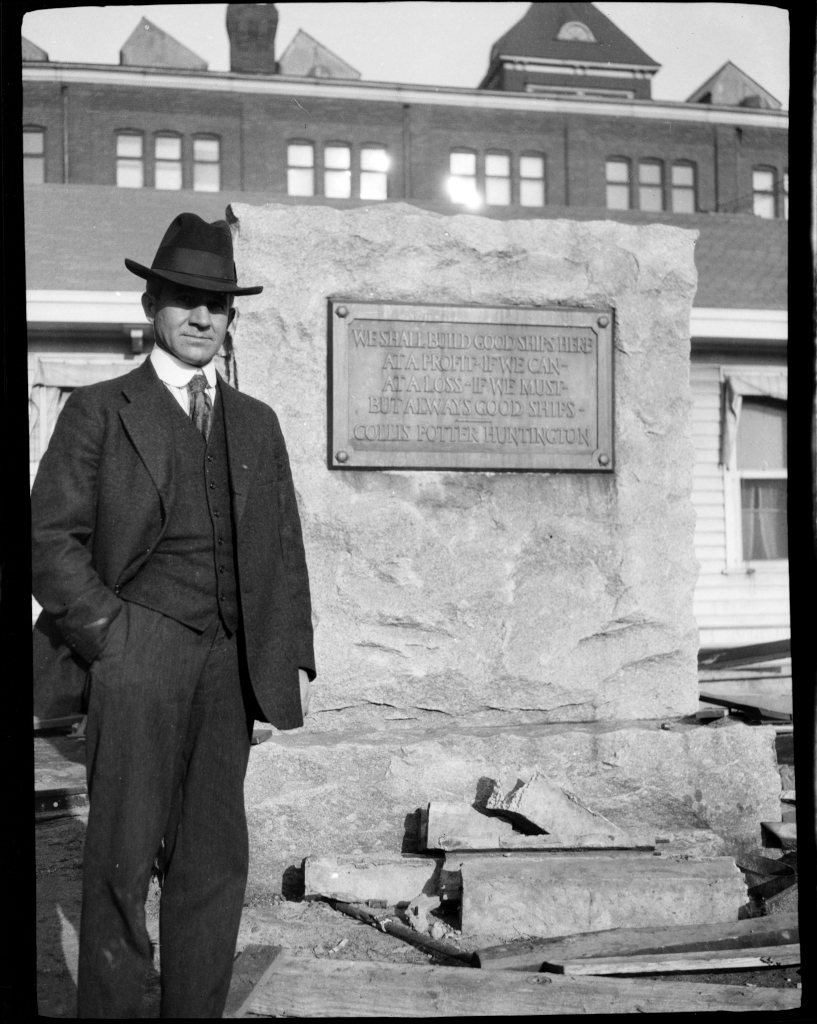

Collis Potter Huntington understood that a successful city required various major industries. His initial vision for Newport News included the railroad and the port. Nevertheless, as he did with other towns like Huntington, West Virginia, he needed yet another major industry for Newport News. The coal from his mines was placed in his trains and delivered to his docks; but he did not control the colliers or have the ability to build or repair those ships.

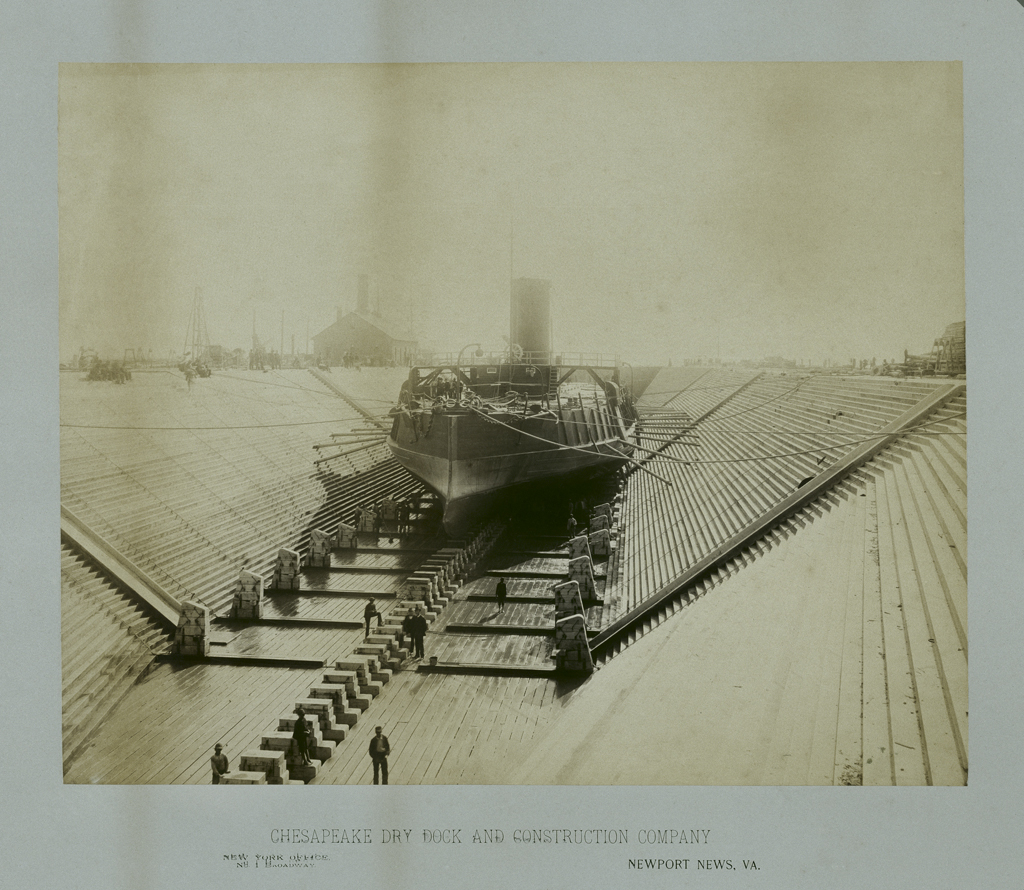

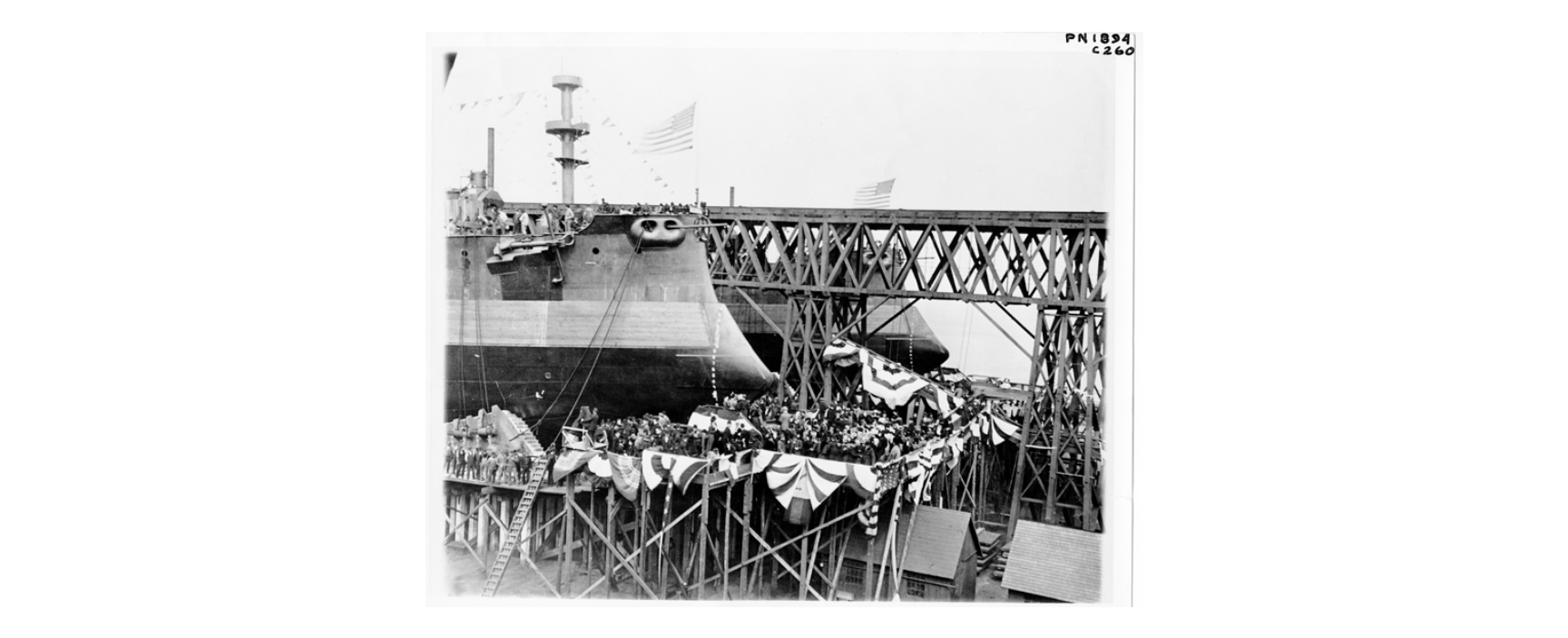

So, in 1886, Huntington created the Chesapeake Dry Dock & Construction Company. Dry Dock #1 officially opened with the docking, at no charge to the US Navy, of the monitor Puritan. It was a grand affair. Huntington attended with two noted poets, Joaquin Miller and Walt Whitman, along with Governor Fitzhugh Lee of Virginia.

Less than a year later, the yard was renamed Newport News Shipbuilding & Drydock Company.

By 1896, the yard received its first US Navy contract to build the USS Kentucky and Kearsarge. By the time of C.P. Huntington’s death in 1900, Newport News was becoming a household name. The city was truly a Huntington legacy with its schools, commercial areas, thriving major industries, and rising population.

NEWPORT NEWS SHIPBUILDING

Arabella Huntington became the owner of the shipyard, and the chairman of its board of directors was C.P. Huntington’s nephew, Henry Edwards “Eddie” Huntington. They later married; but they left the business of the yard to various presidents like Walter Post.

When then- president Albert Hopkins went down with RMS Lusitania on May 7, 1915, Homer Lenoir Ferguson took the helm. Ferguson readied the yard for war with major improvements and expanded ship repair capabilities.

When the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, the yard was quickly expanding. The shipyard received over $100 million in contracts to build battleships, battle cruisers, destroyers and transports, as well as to repair more than 1,400 vessels. Workers worked round-the-clock. On July 4, 1918, known as Liberty Launching Day, Newport News Shipbuilding launched three destroyers: Thomas, Haraden, and Abbott. The Daily Press proclaimed that “Each one was a death blow to Prussianism.” The yard’s employment increased from 7,600 workers to a peak of 12,512 in September 1919.

Workers building ships or the nearby military camps flooded the community and the need for housing was acute. “People who never before thought of taking in any roomers or boarders could not resist the opportunity to make money quickly,” according to the 1919 Municipal Survey. Many boarding houses resorted to the device of “hot bedding” or room sharing. But the officials at the shipyard were finding it hard to attract and keep older, skilled workers, the ones who were needed most.

Shipyard president Homer Ferguson testified before the US Senate and was able to receive financing from the US Emergency Fleet Corporation, an agency of the War Shipping Board. This resulted in the construction of the Shipyard Apartments, across from the yard’s main gate.

Also, the unique Garden City Movement community of Hilton Village was built arising out of the piney woods of Warwick County. Houses appeared as English cottages with churches, schools, a business district, and access to the James River. When the war ended, construction of the village stopped. Consequently, Henry E. Huntington made sure that this community was finished in 1919. Huntington would eventually purchase this federally-funded village so that he could sell the houses to individual homeowners. He also made important improvements to the community such as building the Colony Inn and installing gas lines.

HAMPTON ROADS PORT OF EMBARKATION

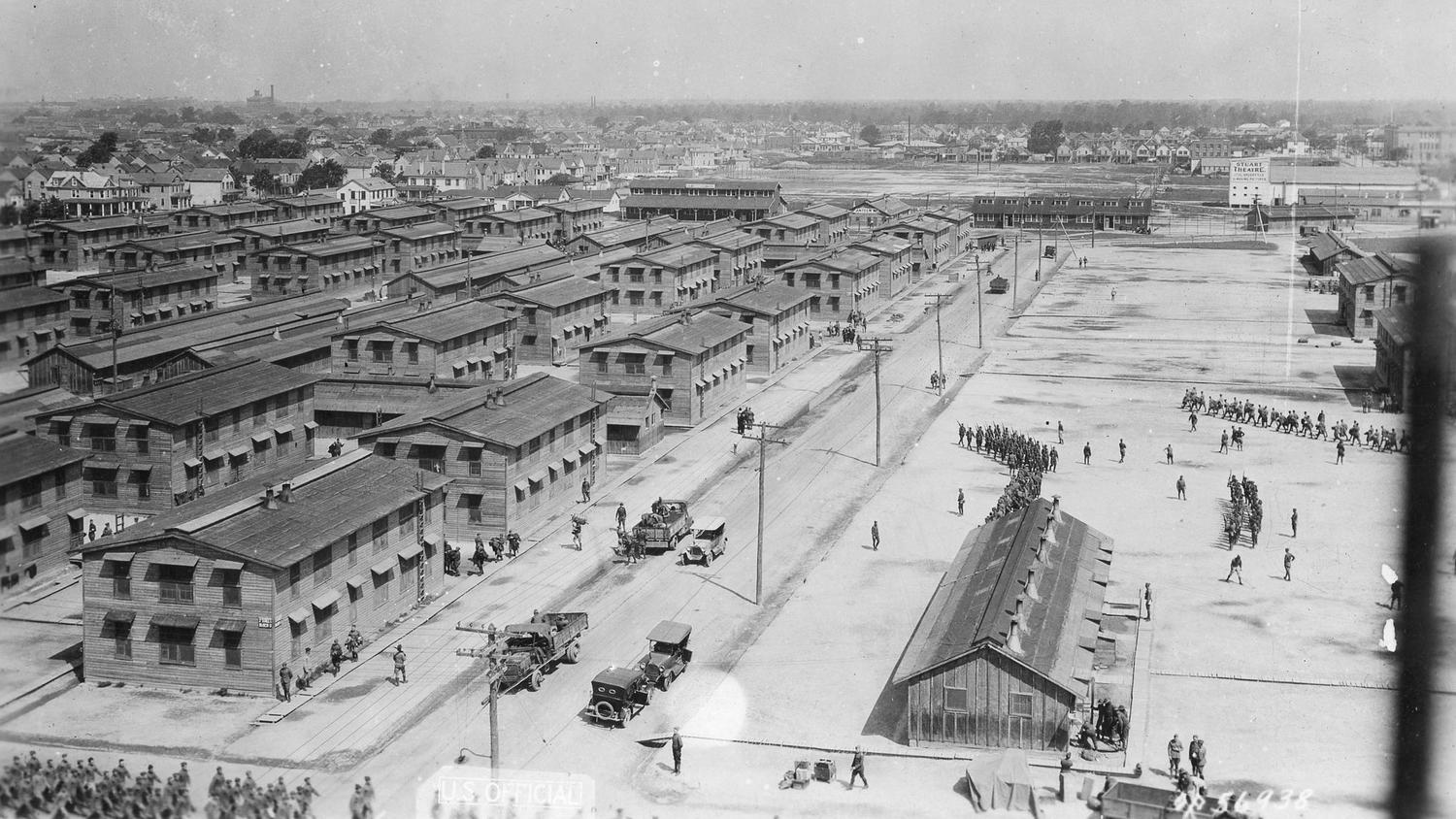

Shortly after the United States declared war, Newport News was named Headquarters, Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation. The US Army took over the operation of the port from the C & O and began to establish embarkation camps and training areas in Newport News and Warwick County. Camps Stuart, Hill, and Alexander existed primarily to process troops going overseas. The town was teaming with troops as Thomas Wolfe later wrote in Look Homeward, Angel:

“Twice a week the troops went through. They stood densely in brown and weary thousands on the pier while a council of officers, tabled at the gangways, went through their clearance papers. Then, each below the sweating torture of his pack, they were filed from the hot furnace of the pier into the hotter prison of the ship. The great ships, with their motley jagged patches of deception, waited in the stream; they slid in and out in unending squadrons.”

Camp Stuart was America’s largest troop clearinghouse and was located between the Small Boat Harbor and Salter’s Creek. It was America’s largest troop clearinghouse during the war with 115,000 soldiers. Camp Hill, positioned along the James River, processed 67,887 men overseas. It also served as the port’s animal embarkation area. The camp’s capacity was 10,000 animals with 900 men to manage the 33,704 horses and 24, 474 mules that were handled by this camp. Due to racial tensions, Camp Hill was divided to create Camp Alexander for Black labor battalions and stevedores.

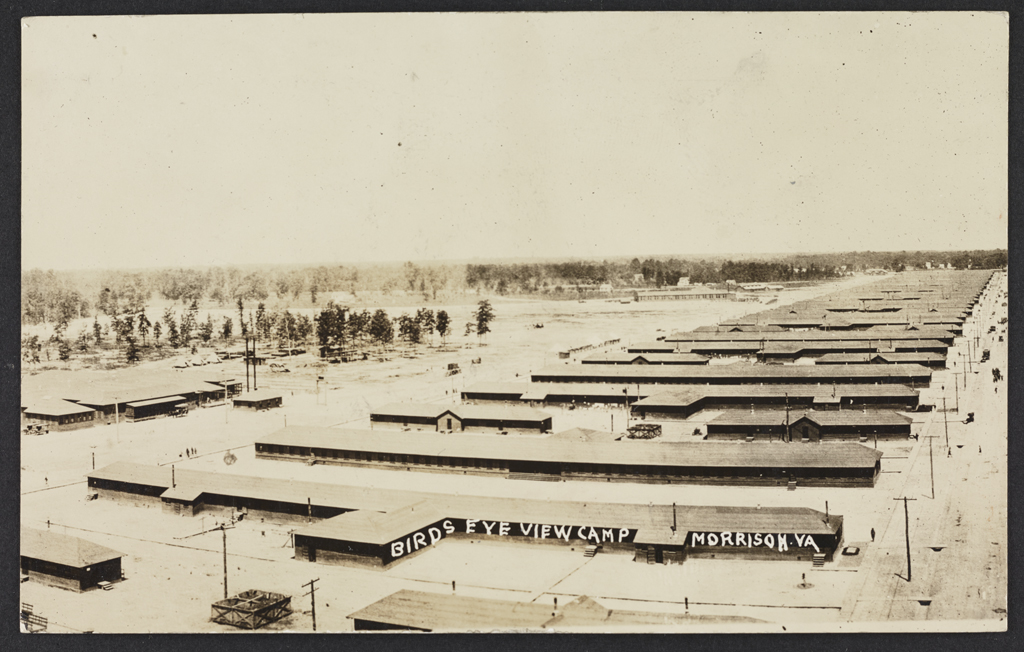

Up Warwick Road, near Hilton Village, was Camp Morrison; it served as an Air Service Depot for the embarkation of balloons and aero squadrons. The final major military base established in Warwick County during World War I was Camp (later Fort) Eustis, built on Mulberry Island with a deep water harbor on Skiffes Creek. Eustis was named for the founder of Fort Monroe’s School of Artillery Practice Bvt. Brigadier General Abraham Eustis. This camp was used for an artillery range. It also became known as the “experimental shop of the Coast Artillery” as soldiers pioneered two new fields of artillery science: anti-aircraft and railway artillery.

The Army Air Service Balloon Observation School, also known as the Lee Hall Balloon School, was also created as part of Camp Eustis. In August alone, 46,130 soldiers were sent to France in 31 transports. A total of 261,820 soldiers were sent overseas from Newport News, while another 441,146 soldiers returned. It was an amazing effort.

“NEWPORT NEWS BLUES”

The citizens of Newport News opened their hearts and homes for all of these servicemen passing through the port. Numerous organizations were established or expanded to handle the influx of soldiers and seamen. In one month, the YMCA on 32nd Street provided 2,200 baths, slept 2,475 soldiers, and served 6,000 meals. Other organizations like the Salvation Army, Women’s Service League, Jewish Welfare Board, and American Library Association endeavored to attend to the servicemen’s needs. The Girl’s Patriotic League knitted socks, rolled bandages, and made masks, while Boy Scouts sold war bonds. Dances were held and concerts were given to provide patriotic enjoyment for the thousands passing through Newport News.

One soldier noted he had never seen such a town and such generous people. He ate very well: “That’s the fifth invitation today and I can’t hold another bit.” But not all was perfect. There was a downtown Newport News riot over merchants profiteering on November 11, 1918. Soldiers suffered greatly from the Spanish Flu, loneliness, and living away from their loved ones.

Two doughboys, Sgt. Hal Oliver and Crp. Willie Shifrin, wrote this popular little ditty, “Newport News Blues”:

Oh! Newport News Blues is the latest fad

Newport News will surely drive you mad,

You start into jazz–then raz-ma-taz-

Oh, way down south – in the land of cotton,

Your Uncle Sam has not forgotten,

You’re a-way-a-way far a-way from Broadway-

They sing and dance that haunting mel-o-dy-

Oh! When you’re down in Newport News

What do they want to play that dog-gone blues for?

The blues of Newport News … Oh! News.

A STEPPING STONE

In less than 60 years after the end of the Civil War, the city of Newport News was internationally known as a shipbuilding center with excellent port facilities. C. P. Huntington’s vision had proven to be more than correct. Huntington laid the groundwork with his railroad and port, both connecting Newport News with all of the United States and nations throughout the world. Newport News surely became a boom town during World War I which provided the platform from which it grew into the thriving city it is today.

References: Quarstein, John V. Hilton Village: America's First Planned Community. Staunton, Virginia: American History Press, 2017. _______________ World War I on the Virginia Peninsula. Dover, New Hampshire: Arcadia Press. 1998. Quarstein, John V., and Parke S. Rouse Jr. Newport News: A Centennial History. Newport News, Virginia: City of Newport News, 1996.