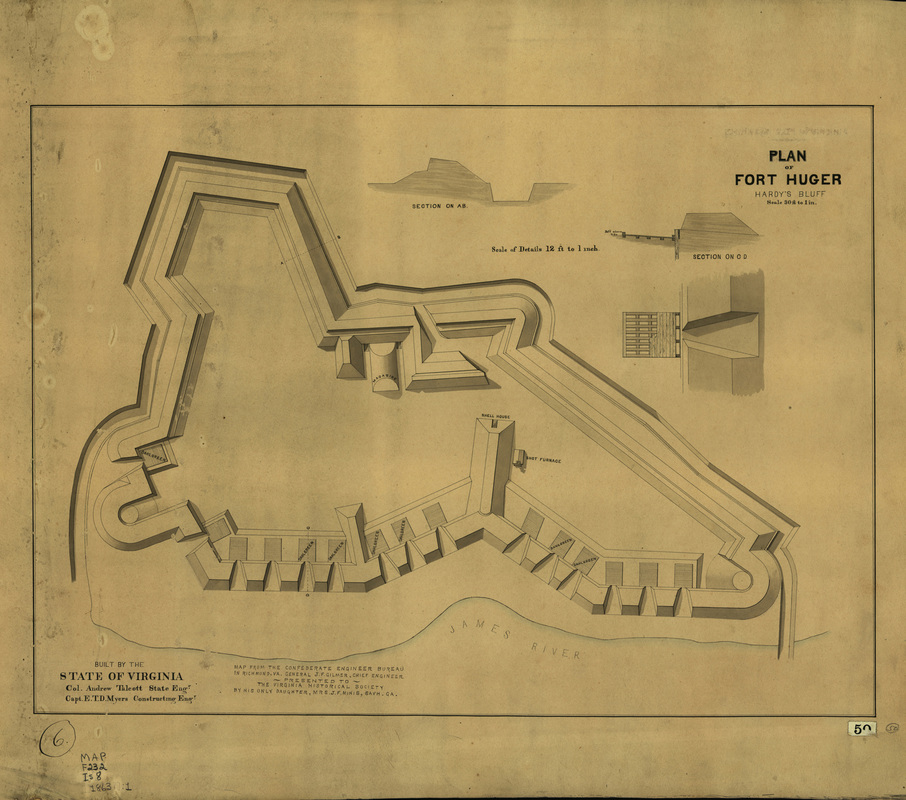

The destruction of CSS Virginia opened the James River pathway to Richmond. President Abraham Lincoln recognized that the Confederate capital was within the grasp of the Union Navy. He wanted to strike quickly into the heart of Confederate Virginia with the hopes that when Monitor and other Union ships attacked Sewells Point on May 8, 1862, USS Galena, captained by Commander John Rodgers, with several other ships, would engage and silence southside Confederate defenses, including Fort Boykins and Fort Huger. These forts were designed to fight wooden ships, not ironclads, and were abandoned. Richmond was only one day’s sail away, and once past Jamestown Island, there was nothing to stop the Union advance upriver.

The Union Flotilla

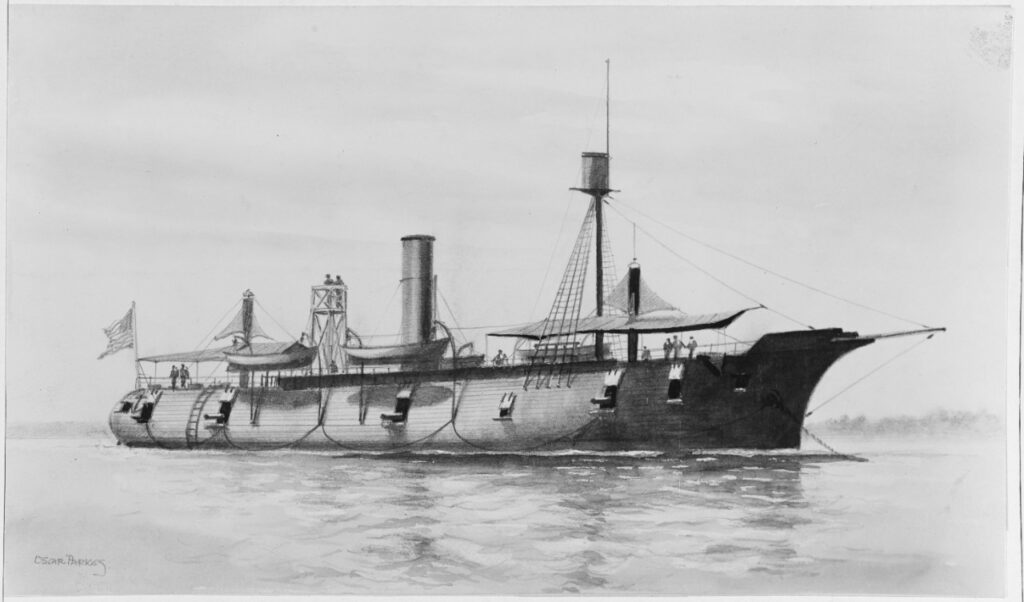

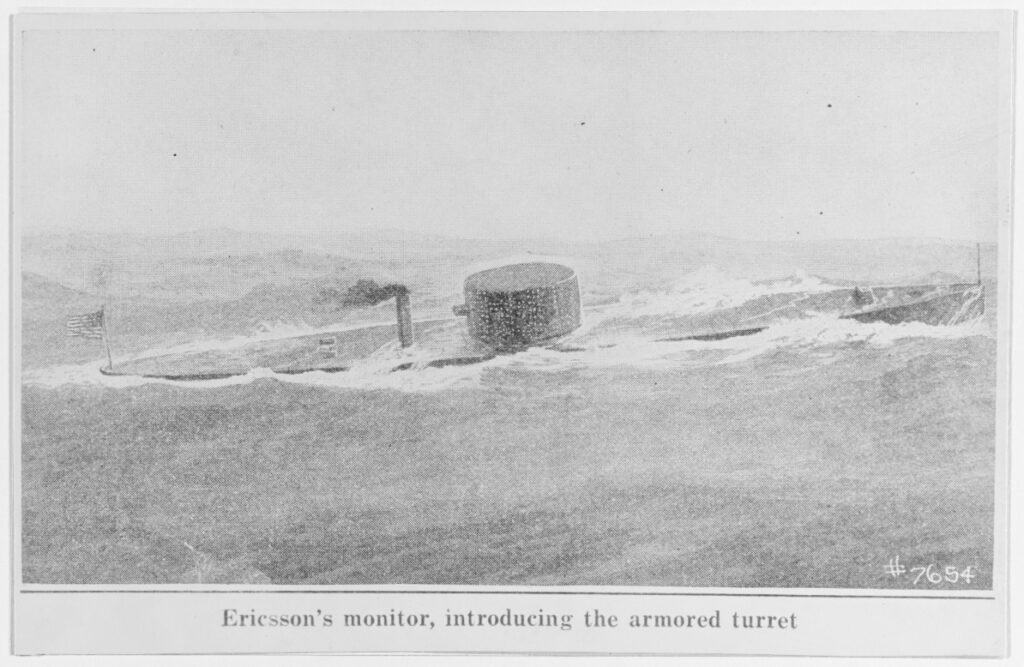

The flotilla was commanded by John Rodgers and would eventually include the ironclads USS Monitor, Galena, and Naugatuck. Galena was one of the three original ironclads and was poorly armored. This ironclad mounted six guns: two 100-pounder Parrott rifles and four XI-inch Dahlgren shell guns.

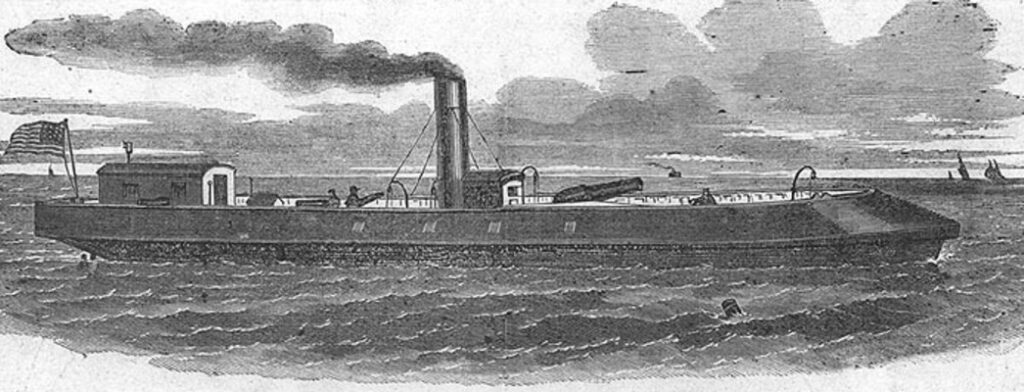

Naugatuck was an experimental ironclad originally conceived by Robert Stevens; however, technology changed before the ship neared completion. The Stevens family completed a smaller version in 1862; however, the US Navy refused to accept it, and Naugatuck joined the US Revenue Cutter Service.

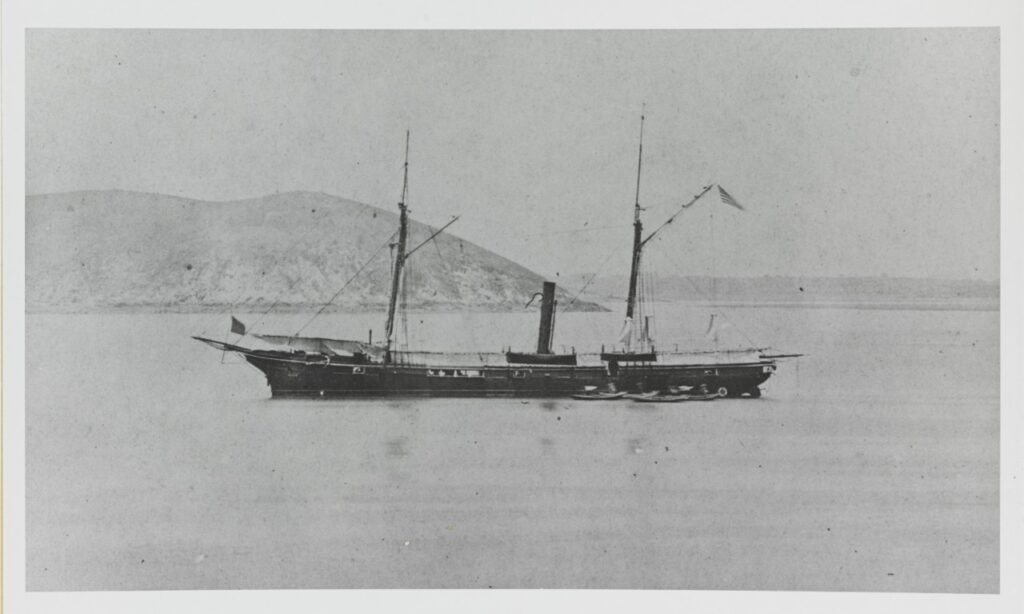

The ironclad was armed with one 100-pounder Parrott. The wooden ships assigned to the expedition were the 90-day gunboat USS Port Royal and the side-wheel double-ender Aroostook.Port Royal was armed with one 100-pounder Parrott rifle, one X-inch Dahlgren shell gun, and six 24-pounder howitzers. The double-ender’s armament included one XI-inch Dahlgren, one 24-pounder Parrott rifle, and two 24-pounder howitzers. [1] Despite the rush to reach Richmond, the squadron had to stop and disarm every Confederate position below City Point. The Union ships reached the confluence of the James and Appomattox rivers by May 13.

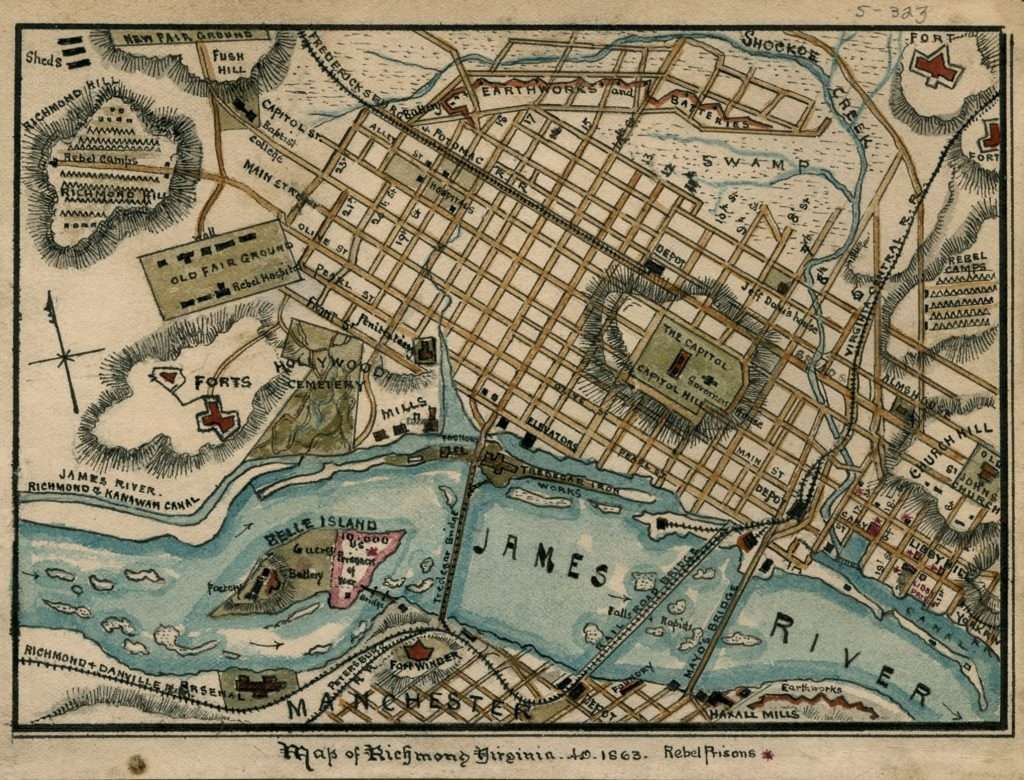

Meanwhile, the Confederate capital was in an uproar over the approach of the Union fleet. The Confederate government began preparations to abandon the capital, and the city’s administration vowed to burn Richmond rather than see it fall into Union hands. Richmond’s lack of river defenses had been an issue for several months. Heretofore, the city had felt secure with Virginia serving as the river’s gatekeeper. Now that the ironclad was gone and the fortifications on the lower James powerless to stop the Federal ironclads, all appeared lost. General Robert E. Lee, however, was determined that Richmond “shall not be given up” and turned his attention to Drewry’s Bluff. He sent his son, Colonel George Washington Custis Lee, there to rush forward the earthwork construction.

Fortifying the Bluff

Drewry’s Bluff was a natural defensive position on the south side of the James River, located eight miles below Richmond. The bluff, rising almost 100 feet above the river, commanded a sharp bend in the river and was the last place to effectively mount a defense before reaching Richmond. Capt. Alfred L. Rives of the Confederate Engineers Bureau had surveyed the James River defenses in March 1862. Rives and fellow engineer Lt. Charles Mason studied the river with Capt. Augustus Hermann Drewry, commander of the Southside Heavy Artillery, to identify a suitable location to fortify and obstruct the river. Property owned by Drewry himself was selected. Lt. Mason designed the fort and Capt. Drewry’s command was assigned to build and defend it. As the earthwork known as Ft. Darling began to take shape, three heavy guns, two XIII-inch and one X-inch Columbiads, were placed in battery. Little had been accomplished when Commander John Randolph Tucker’s James River Squadron steamed upriver on May 9, 1862. When Tucker passed the bluff, he noticed the unpreparedness of the defenses. He immediately wrote to Commander Ebenezer Farrand, CSN, the recently appointed commander of Ft. Darling: “I feel very anxious for the fate of Richmond and would be happy to see you about the obstructive placed there–I think no time should be lost in making this point impassable.” [2]

Farrand was ordered to “lose not a moment in adopting and perfecting measures to prevent the enemy’s vessels from passing the river.”[3] Rodgers, investigating each rebel fort below City Point, gave the Confederates precious time to enhance their defenses. Reinforcements sent to the bluff included the Bedford Artillery, some infantry from Brig. Gen. William Mahone’s brigade, and the crew of CSS Virginia. Catesby Jones and his shipmates arrived at Drewry’s Bluff on the morning of May 13. He understood that “the enemy is in the river, and extraordinary exertions must be made to reply to him.” [4]

Jones organized his crew members into work parties, assisting Commander John Randolph Tucker’s sailors in constructing new gun emplacements. The men worked diligently, in the rain and mud, for the next two days. By the morning of May 15, the seamen had mounted several heavy guns taken from CSS Patrick Henry and Jamestown. Tucker’s men mounted a seven-inch rifle in an earth-covered log casemate located near the entrance to Fort Darling.

The Confederates made other arrangements to block the Union ship’s ability to pass the bluff. Jamestown was sunk, along with several other stone-laden vessels, like the schooner John W. Roach, approximately 300 yards in front of Fort Darling. This effectively closed the river to the federal vessels. Tucker held above the obstructions the remaining James River Squadron gunboats: CSS Patrick Henry, Teaser, and Beaufort. These ships were ready to engage any Union warship that might make its way past the defenses. Capt. John D. Simms and his detachment of Marines dug rifle pits below the bluff. Lt. John Taylor Wood deployed sailors as sharpshooters on the opposite bank of the river to harass the Union ships as they neared Drewry’s Bluff.

The Battle Begins

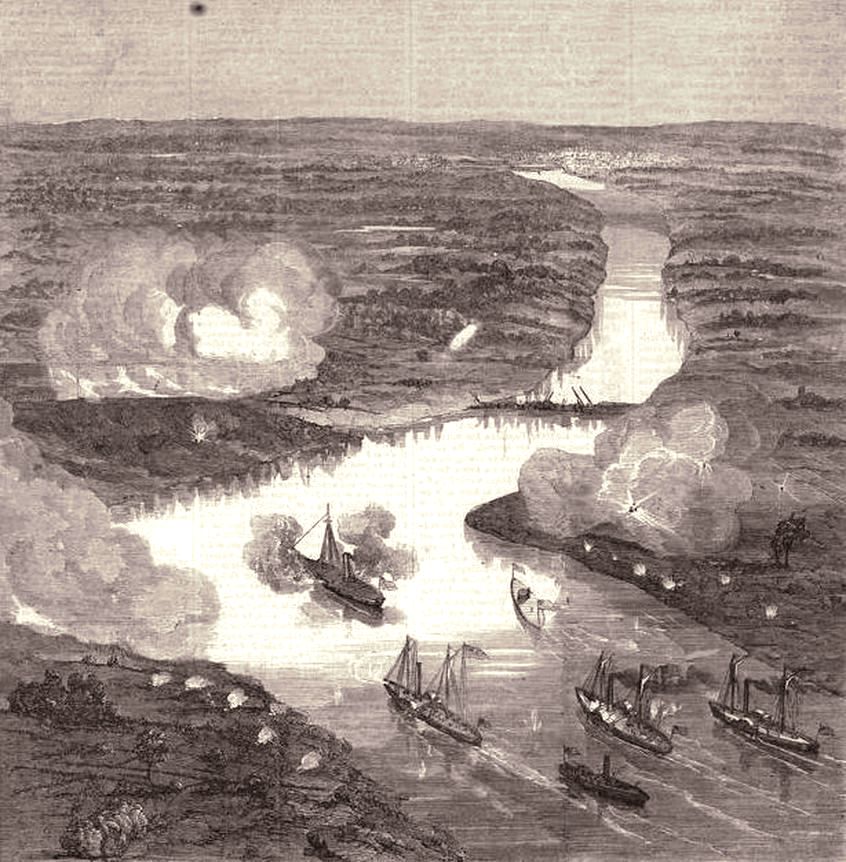

At about 6:30 am on May 15, Rodgers’s command got underway from its anchorage and steamed around the bend at Chaffin’s Bluff, with Rodgers in Galena taking the lead. The ironclad’s commander decided that Galena should be tested under fire.”I was convinced as soon as I came aboard that she would be riddled with shot,” Rodgers later wrote, “but the public thought differently, and I resolved to give the matter a fair trial.” [5] Galena had an experimental hull design, utilizing three overlapped one-inch plates for protection. The ironclad’s sides curved from the waterline to the top deck to give protection from opposing ships. However, this armor-clapboard design would provide inadequate protection against plunging shot, since the deck was built solely of wood.

Despite these weaknesses, Galena headed the squadron followed by Monitor, Aroostook, Port Royal, and Naugatuck. As the flotilla passed Chaffin’s Bluff Confederate, riflemen began to pepper the Union warships. One sharpshooter picked off the leadsman on Galena. His replacement was also wounded. Assistant Paymaster William Keeler of Monitor noted that one ball “passed between my legs & another just over Lieutenant Greene’s head.”[6] Monitor’s crew stayed within their ironclad, despite the heat, throughout the engagement, while the wooden gunboats had to contend with the constant sniping, which they countered with their 24-pounders.

Rodgers maneuvered his ironclad into position 600 yards from the shore. The river was very narrow at this point, but Rodgers gracefully swung into action. Virginia’s former boatswain Charles H. Hasker was amazed by how Rodgers placed Galena into action with such “neatness and precision.” Hasker, who had previously served in the Royal Navy, called the maneuver “one of the most masterful pieces of seamanship of the whole war.” [7]

Rodgers knew that he must reduce the batteries on the bluff and then disperse with the rebel sharpshooters before he could open the door to Richmond through the obstructions. The federal fleet was immediately at a disadvantage. The obstructions blocked any opportunity to run past the batteries toward Richmond. Monitor was anchored astern of Galena. The other gunboats anchored about a half mile downriver off the mouth of Cornelius Creek. These vessels had to use their howitzers to contend with snipers as well as their heavy guns to shell the bluff. After 17 rounds, Naugatuck’s 100-pounder Parrott rifle burst. Thereafter the experimental ironclad could only shell the shoreline with its 24-pounders. Port Royal was also damaged during the fight as one shot crashed through the port bow of the gunboat and had to break off action for repairs. Once the gunboat came back into action, Port Royal was struck again by a heavy shot amidships causing minor damage. Nevertheless, the ship remained in action.

Galena was the primary target for the Confederate gunners. The ironclad had anchored “within point-blank range” of Fort Darling’s batteries, and the cannonade began to take effect. Ebenezer Farrand noted: “Nearly every one of our shots telling upon her iron surfaces.” [8] Seeing that Galena was being pounded by shot, Lt. William Jeffers moved Monitor virtually abreast of the larger ironclad in an effort to draw some of the Confederate shot away from Galena. Monitor’s new position and the dimensions of the turret’s gun ports did not allow the ironclad to elevate its two powerful XI-inch shell guns enough to hit the rebel gun positions. The Drewry’s Bluff cannoneers, knowing about Monitor’s shot-proof qualities, wasted little ammunition on the ironclad. “Three shot struck us,” Paymaster Keeler noted, “making deep indentations but doing us no real harm.”[9] Eventually, Monitor backed downstream and continued a deliberate fire from its final position.

Monitor’s crew was safe from the sharpshooter’s fire and shot from the batteries; however, “all suffered terribly for the want of fresh air. It was one of those warm, muggy days with a very rare atmosphere which, shut up closely like we were, made ventilation very difficult. At times we were filled with powder smoke below threatening suffocation to us all.”[10] The outside humidity, coupled with the heat from the engines, led Jeffers to estimate that it was 140 degrees within the turret. The hell-like qualities of a mixture of coal fumes, smoke, as well as powder smoke and sulfuric smells, made it unbearable within Monitor. Some of the men had to be taken out of the turret or engine room in order to breathe less infected air.

When the Union ships first steamed into sight on May 15, Farrand readied his command. As Galena maneuvered into position, the three guns in the main battery opened fire. Captain Drewry fired the first shot, which passed over the ironclad into the east side of the river. Even though the Confederates appeared to have the advantage with their defensive position atop the bluff and their use of plunging shot, they still encountered numerous problems. The X-inch Columbiad manned by the Bedford Artillery was loaded with a double charge of powder. Consequently, when the Columbiad was fired, it recoiled off its truck.

This heavy gun was not brought back into action until near the end of the engagement. Also, the recent heavy rains caused the casemate protecting the seven-inch Brooke gun to collapse, burying the sailors manning the gun after firing just a few shots. The crew dug themselves out and somehow was able to bring the Brooke gun back into action just before the battle concluded.

Commander Tucker commanded the five naval guns manned by sailors from CSS Virginia and Patrick Henry, while Catesby Jones was stationed at the Southside Artillery’s position to assist the volunteer artillerists in managing their guns. Jones was so exhausted by his efforts of the past five days that he actually dozed off on a shell box during the engagement. The naval battle, despite mounting very powerful ordnance, did not play as major a role as the seaman wished. Positioned to the left of the fort on the bluff’s brow, the sailors continued to bang away at the Union vessels throughout the battle and often needlessly exposed themselves to enemy fire.

Union cannon fire was rather effective early in the battle and inflicted 13 casualties. Several men were killed by fragments from a 100-pounder shell from Galena. Thomas Mann of the Southside Artillery remembered:

Shells from the Galena passed just over the crest of our parapets and

Exploded in our rear, scattering their fragments in every direction, together

With the sounds of the shells from the others, which flew wide of the mark,

Mingled with the roar of our guns, was the most startling, terrifying, diabolical

Sound which I had every heard or ever expected to hear again.[11]

“We could see large clouds of dirt & sand fly as shell after shell from our guns exploded in the rebel works,” Keeler remembered, “& no sooner was a gun silenced apparently in one portion of the batteries than they opened from some other part or from some new & heretofore unseen battery.” [12] One way the Confederates avoided casualties was that the men retreated into bomb proofs during periods of heavy Union shelling. When federal fire slackened, the defenders would rush back to their guns to return fire. This action also helped to conserve the Confederates’ limited ammunition supply. Despite the Union flotilla sending “their iron messengers with remarkable accuracy,” the “batteries on the Rebel side were beautifully served,” noted John Rodgers, “and put shot through our sides with great precision.”[13]

Galena Under Fire

As the duel between the batteries and warships continued through the morning, Farrand noticed he was running low on ammunition, so he let the Southside Heavy Artillery soldiers take a half-hour break. When the Confederate gunfire slackened, Rodgers thought his squadron was about to silence the Confederate guns; however, he also learned that Galena was running out of ammunition for its XI-inch Dahlgrens. Rodgers had to switch from explosive shells to solid shot, which had little effect on the rebel works. Farrand ordered Drewry’s men back to their Columbiads, and they reopened their cannonade of Galena with terrible effect. Every shot from the Confederate cannons seemed to strike the Union ironclad. Galena’s armor was broken, bent, and pierced in many places.

Despite the advantages of the Southerners’ position, some of the defenders, like Thomas Mann, thought that the federals “would finally overcome us.”[14] Nevertheless, the battle was decided in the Confederates’ favor with their heavy ordnance, constantly sending shot and shell into the Union vessels. They almost never missed their targets. Galena was struck by 43 projectiles. Its weak iron plating was penetrated thirteen times during the engagement. At about 11:05 a.m., the telling shot struck the ironclad. A shell from one of Patrick Henry’s guns, manned by former Virginia crew members, crashed through Galena’s bow and exploded. The shell ignited a cartridge, then being handled by a powder monkey, killing three men and wounding several others. The explosion sent “volumes of smoke,” according to Paymaster Keeler, “…issuing from the Galena’s ports & hatches & the cry went through us that she was on fire, or a shot had penetrated her boilers—her men poured out of her open ports on the side opposite the batteries, clinging to the anchor, to loose ropes…We at once raised our anchor to go to her assistance but found that she did not need it.”[15]

When the Confederates saw the smoke and flames rise from Galena, the gunners on the bluff “gave her three hearty cheers as she slipped her cables and moved downriver.” [16]

It appeared to the Confederates that Galena was retreating because of the explosion. Rodgers, who had barely escaped injury when the final shell exploded on his ironclad’s gun deck, had already decided to hoist the signal to break off action. Rodgers knew that his ship was running low on ammunition and had barely survived a damaging hail of Confederate fire. The entire squadron retreated down the river toward City Point. As he watched his enemy steam away from Drewry’s Bluff, Lt. John Taylor Wood, formerly of CSS Virginia, hailed Monitor’s pilothouse from the riverbank shouting, “Tell Captain Jeffers that is not the right way to Richmond.”[17]

Rodgers’s squadron endured “a perfect tempest of iron raining down and around us.” Galena suffered the greatest damage: its railings were shot away, the smokestack was riddled, and 24 crew members were listed as casualties. The battle demonstrated that the ironclad was “not shot-proof.” [18]

William Keeler of USS Monitor commented that Galena’s iron sides were pierced through and through by the heavy shot, apparently offering no more resistance than an eggshell,” verifying the opinion that “she was beneath naval criticism.” When the paymaster went aboard Galena, he thought that the ship:

Looked like a slaughterhouse..of human beings. Here was a body with the

hand, one arm & part of the breast torn off by a bursting shell–another

With the top of his head taken off the brains still steaming on the deck,

Partly across him lay one with both legs taken off at the hips & at

a little distance was another completely disembowel. The sides & ceiling

, overhead, the ropes & guns were spattered with blood & brains & lumps

of flesh while the decks were covered with large parts of half coagulated

Blood & strewn with portions of skulls, fragments of shells, arms, legs,

Hands, pieces of flesh & iron, splinters of wood & broken weapons were

Mixed in one confused, horrible mass. [19 ]

Rodgers knew that Drewry’s Bluff could be taken with a joint army-navy assault. Unfortunately, Major General George McClellan advised Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough that he had no troops to spare for such an attack. The federal navy was just eight miles from Richmond and would not reach that close to Richmond until April 1865.

A Win for the Confederates

The Battle of Drewry’s Bluff was a dramatic Confederate victory. Richmond was under immediate threat of being captured or at least shelled and destroyed by the Union flotilla. Yet, the cannoneers at Drewry’s Bluff had saved the capital. Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis had both ridden to Drewry’s Bluff when they heard the sound of heavy artillery. They arrived near the battle’s conclusion and “seemed well pleased with the results of the engagement.” [20] Commander Ebenezer Farrand was even more exuberant: “There is no doubt we struck them a hard blow.” Farrand concluded his battle report, stating, “The last was seen of them they were steaming down river.”

One Southern patriot celebrated the Union repulse with a short poem:

The Monitor was astonished,

And the Galena admonished,

And their efforts to ascend the stream

We’re mocked at.

While the dreaded Naugatuck

With the hardest kind of luck,

Was very nearly knocked

Into a cocked-hat.[21]

“The people of Richmond seemed to realize that we had saved the city from capture.” Midshipman Hardin Littlpage remembered, “and early in the after-noon wagon-loads of good things came down–cakes and pies, and confections of all sorts accompanied by a delegation of Richmond ladies.” [22] Midshipman William F. Clayton recalled, “Surely, from the quantity and quality, the markets must have been raked clean and the dear girls sat up all night cooking.” [23]

While the battle saved Richmond from capture by the US Navy, Keeler considered:

We do not regard the matter in the light of a defeat as we accomplished

Our purpose, which was to make a reconnaissance [sic}, ascertain the nature

& extent of the obstructions, the position & strength of the batteries. We

found them of such a nature that it was an impossibility to force them with

the means at our command & the river so narrow it is equally impossible

to bring a much larger force to bear. [24]

It was indeed a major Union defeat, as Fireman George Geer wrote his wife: “We have been fighting all day and have come off 2nd best.”[25]

Drewry’s Bluff remained the sole gatekeeping blocking the James River approach to the Confederate capital until the commissioning of the ironclad ram CSS Richmond. The days immediately before and after this May 15 engagement should have been utilized by the Union for a more concentrated Army-Navy assault on Richmond. Once past Drewry’s Bluff, Richmond would have surrendered and, perhaps, the war might have been over.

Endnotes

1. Paul Silverston,Civil War Navies 1854-1882, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute press, 2001,

2.John M, Coski, Capital Navy: The Men, Ship’s, and Operations of the James River Squadron, Campbell, CA: Savas Woodbury Publishers, 1996, p.41

3. U.S, Department of the Navy, Official Records of the Union and Confederate in the War of the Rebellion, (hereinafter referred to as ORN), Washington, D.C.: U, S. Government Printing Office, 1894, Ser. 1, vol. 7, p. 636.

4. _____ Ser. 1, vol. 7, 799.

5. James Russell Soley, “The Navy in the Peninsular Campaign,” In Battle and Leaders of the Civil War, vol 2, edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, New York: Century Co., 1887, p.229-270

6. Robert W. Daley, How the Merrimac Won: The Strategic Story of the CSS Virginia, New York: Crowell Inc., 1957, p126’.

7, Soley, “The Navy in the Peninsular Campaign,” p.270.

8.ORN, ser. 1, vol.7,. 369.

9. Daley, Aboard the USS Monitor, p.126

10, IBID, p. 126.(

11. Samuel A. Mann, “New Light on the Great Drewry’s Bluff Fight,” SouthernHistorical Society Papers 34, p.92-93,

12. Daly, Aboard the USS Monitor, 128.

13. ORN, ser. I, vol. 7, p. 370.

14. Mann. “New Light on the Great Drewry’s Bluff Fight, p. 92.

15. Daly, Aboard the USS Monitor,” p. 128.

16. ORN, ser. 1, vol.7, 370.

17. Thomas J. Scharf, History of the Confederate States Navy from IT’S Organization to the Surrender of Its Last Vessel, New York: Rogers & Sherwood, 1887; reprint, New York; Grameray Books, Random House publishing, Inc., 1996, p.764.

18. ORN, I, 7, 357.

19. Daly, Aboard the USS Monitor, pp. 129-30.

20. Mann, “New Light on the Great Drewry’s Bluff Fight,’ p. 95.

21. IBID.

22. Hardin Beverly Littlepage, “With the Crew of the Virginia,” Civil War Times Illustrated (May 1974): p.42.

23. Coski, Capital Navy, p.47.

24. Daly, Aboard the USS Monitor, p.129.

25. Marvel, The Monitor Chronicles, p.72.