Sometimes it takes just one object in the Collection to open up a world of exciting stories. In this case, an oil painting caught my eye the other day and reminded me of a history that excited me when I first learned about it.

During the American Revolution the Americans had a fledgling Navy, made up of the small fleets that each state could muster together. These ships were not able to match the well-trained, battle-hardened British Navy, so the Americans turned to privateers to help in the fight. A privateer was a private citizen who owned a ship and offered to arm that ship to fight against the British merchants. They had a better chance of success fighting merchants than a ship of the line, plus we needed the merchants’ cargo and supplies. In return the privateers received a portion of the money from the sale of the captured prize ship and the goods it carried. The profits could be high, but so was the danger. Whether these sailors were pirates or not completely depended on the paperwork and whose side of the war you were on.

Privateering was not a new concept with the American Revolution and there were many well established laws and regulations that went back centuries. Privateers carried letters of marque, signed and stamped documents that gave them permission to attack enemy ships and bring the prize ship back to port to be sold. The letter of marque was what made it official and legal. Unless of course you were on the British side, in which case that made you a pirate in every sense of the word and destined for a punishment befitting such an outlaw. Their stance was that the Americans were not a legitimate country, just badly behaved colonies, and therefore had no legal standing to provide such letters. Poof went the letter and poof went your freedom, and often your life.

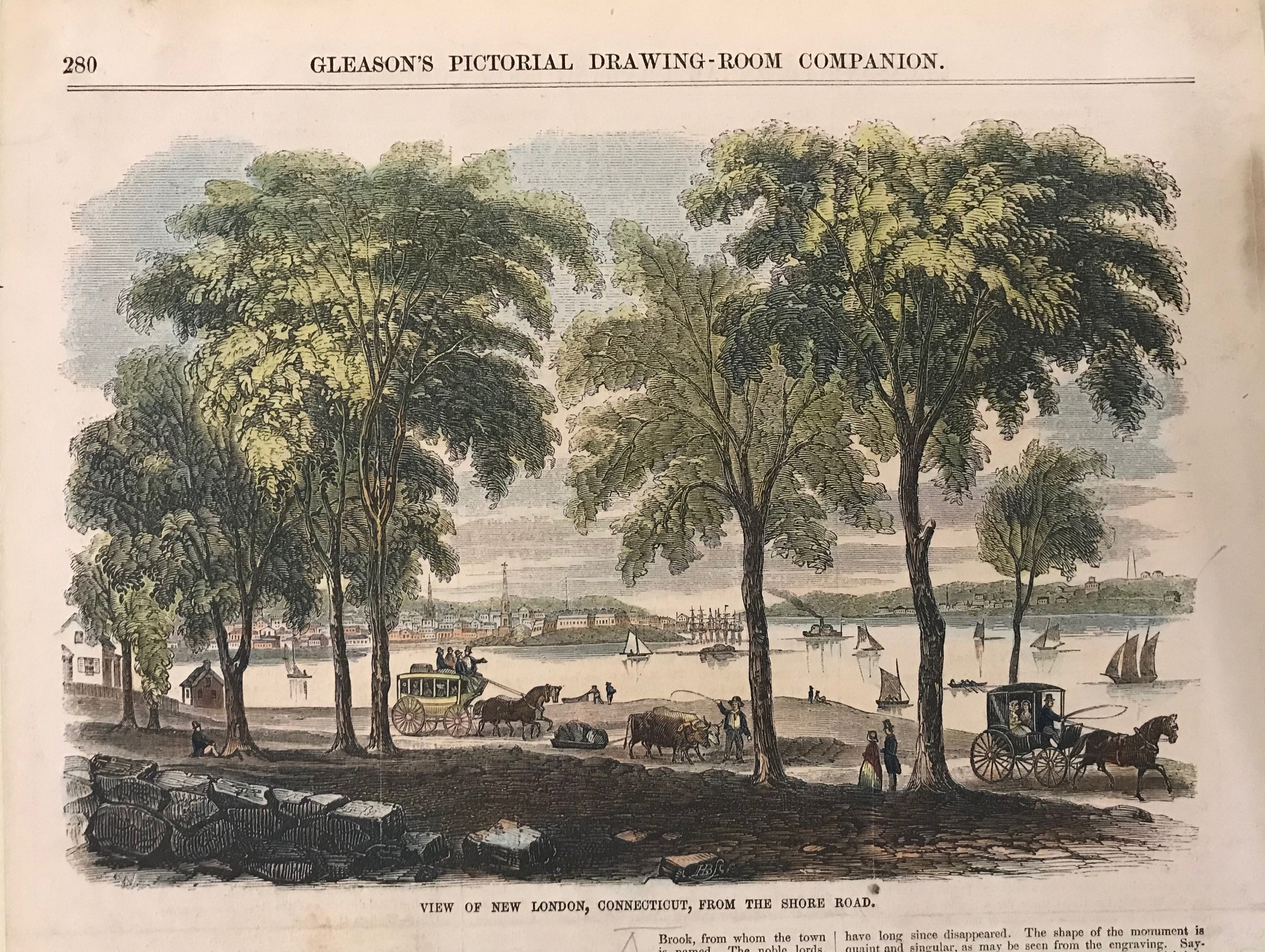

New London, Connecticut was a great home port for privateers. It has easy access to the Long Island Sound and the Atlantic Ocean, the depth of the Thames River (pronounced here like James, not like the River Thames over in London) is deep enough for larger ships, and it is near New York City, which the British occupied. To round out how great New London was for this, they were home to a large whaling industry with many ships and sailors already in the area.

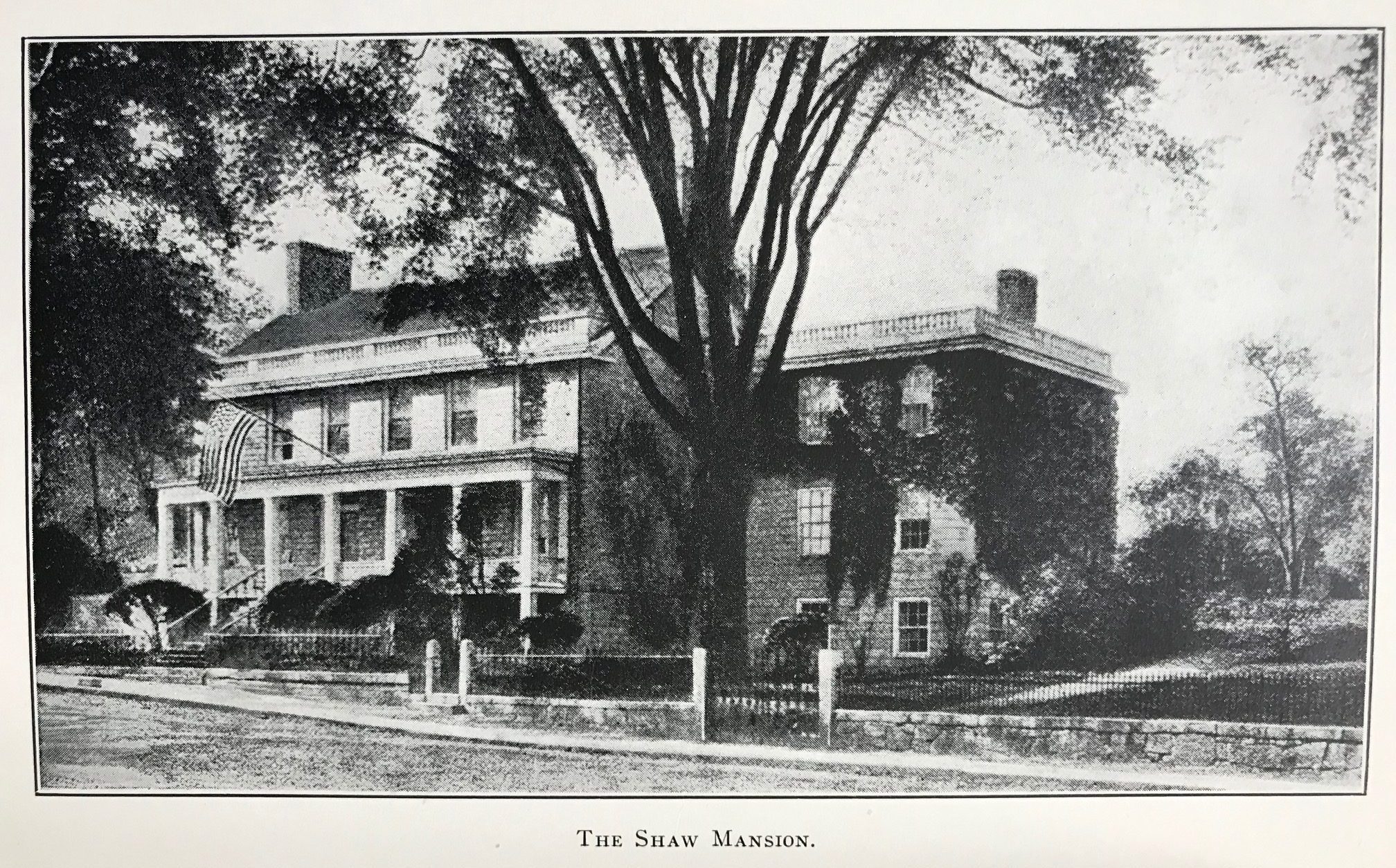

The local privateers who operated out of New London had to go first to the home of Connecticut’s Naval Agent, Nathaniel Shaw, Jr. His father was a wealthy sea captain of the same name who oversaw the construction of his home by French refugees from Nova Scotia in 1756. He provided them with jobs cutting the granite from his property near the river to then use to build the house. The stones come in handy later in this story.

Shaw Jr. used the house as his headquarters, issuing the letters of marque, organizing the sale of the prize ships, and operating his own privateering fleet. The privateers who sailed out of New London were incredibly successful and contributed to the $18 million loss of British shipping during the war ($302 million in today’s money, according to the National Park Service). As you can imagine, the British were more than ready to put an end to this “piracy.”

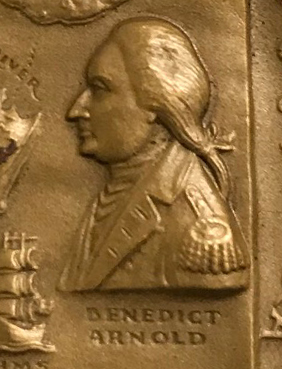

This is where we add the villain of our story, Benedict Arnold. Arnold was born in Norwich, CT, just about 15 miles north of New London. He knew the area, and he knew the people who lived there. After he joined the British he received a commission as a Brigadier General and Arnold led a raid on Richmond, Virginia. Then he and the British turned their sights on Connecticut, specifically New London and Groton, just across the Thames River.

New London was prepared for the British, or so they thought. There were two forts protecting the river, Fort Trumbull in New London built in 1777 and Fort Griswold on the Groton side of the river, built in 1775. On the morning of September 6, 1781 a lookout at Fort Griswold, Rufus Avery, saw the British fleet at the mouth of the river and sounded the alarm.

Remember when I said that Arnold knew the area and the people? He also knew their signals. Fort Griswold fired two cannon shots, the signal for an attack, but one of the British ships fired a perfectly timed third shot, which to anyone in the surrounding region would have meant that a privateer was returning with a prize ship. These were very different signals calling for very different reactions, so the local militia did not quickly run to protect the forts. The men who happened to be at the forts had to send someone out to explain the shots and call for help, which left even fewer defenders at the forts.

Arnold had arrived with ships full of approximately 1,700 British, Hessian, and loyalist troops, which he split between the two sides of the Thames River. Arnold chose to join the New London side of the attack possibly because it was the larger of the two towns, and the one with the home of Nathaniel Shaw, Jr. (the headquarters of the Connecticut Naval Agent and the privateers). Arnold knew Shaw, and they had even corresponded about Arnold possibly purchasing a share of Shaw’s privateer, the General Putnam. The cost for 1/16th ownership ended up being too much for Arnold to afford so he declined the partnership in 1778. However, Arnold was part owner of a privateering sloop, John. Arnold wrote to Shaw on August 10, 1780 asking for him to settle a financial dispute between himself as part owner and the captain of the John. A little over a year later he stood in New London on very different terms.

As Arnold and his troops approached, Captain Adam Shapley and his 23 soldiers at Fort Trumbull fired a volley and then quickly realized they were more than outnumbered, so they followed orders to spike the cannons and row across the river to help defend Fort Griswold. Arnold’s troops began burning New London, and made a point to set fire to the Shaw Mansion.

Thankfully for the Shaw family, the house was built of those granite stones that the French refugees had helped carve out just 25 years earlier. It’s more difficult to burn a stone house than wood, and while the British did set fire to it, the flames did not cause much damage and the house survived. The same could not be said for most of the other buildings on the New London waterfront, which became an inferno. According to an 1895 book by Frances Manwaring Caulkins, Arnold’s troops burned 65 homes, 31 stores and warehouses, 18 mechanic shops, the wharves, the custom house, the jailhouse, and the courthouse. They also burned approximately 10 armed ships, but most of the ships Arnold had hoped to take or destroy had managed to escape up the river toward his hometown of Norwich.

The situation in New London was bad (to put it mildly), but things were about to be devastating in Groton. The troops under Lieutenant Colonel Edmund Eyre and Major William Montgomery went to Fort Griswold after landing, and they found an earthen fort at the top of a steep hill with just over 160 men led by Colonel William Ledyard. Despite being way outnumbered the Americans in the fort managed to initially repulse the British attacks, but the fort fell quickly and the British entered. Both Eyre and Montgomery died, along with three other British officers for a reported total of 51 dead on the British side, plus nearly 130 wounded.

Ledyard called for the Americans to surrender, at which point the history is a little murky. The American reports state that few Americans had been wounded at the time when British Major Bromfield asked who commanded the fort. Ledyard’s response was, “I did sir, but you do now” as he handed his sword to Bromfield. Major Bromfield took the sword and immediately plunged it into Ledyard, killing him and setting off a massacre. The British reports make no mention of the events after the surrender. All told, the Battle of Groton Heights lasted approximately 40 minutes and left 88 Americans dead and 35 wounded, with the rest taken as prisoners. Out of 160 men this was a major loss.

Of the killed and wounded there were two black men and one Pequot man who fought that day. Lambo Latham was killed along with Jordan Freeman, a former slave who reportedly stabbed Major Montgomery as he climbed over the fort walls. Tom Wansuc, a Pequot Indian, received a wound to his neck but the British paroled him.

To make matters worse, as the British began to leave they loaded wounded Americans on a cart for transportation down the steep hill to the ships waiting in the river. The men holding the heavy cart lost control of it and the cart careened downhill, picking up speed until it crashed into a tree. The men from the cart were now twice wounded and in too bad of a condition to take as prisoners, so the British left them at a nearby home. That happened to belong to one of the wounded Americans, Ebenezer Avery, though it isn’t known if he was in the cart. His house became a makeshift hospital, and twenty two of the men who died or were wounded were from the Avery family.

The region remembers the Battle of Groton Heights today with a large granite obelisk constructed between 1826 and 1830. Rising 135’ atop the Groton hillside, the monument is visible in our painting and many other images of the two cities. In addition to that, both forts are now state parks and the Shaw Mansion and Ebenezer Avery House are museums. If you are ever in southeastern Connecticut, make sure to stop by to learn about and honor the events of September 6, 1781, just six weeks before the surrender at Yorktown (another place you could visit!). It’s amazing how quickly an area can go from a successful whaling fleet to successful privateering, thus earning the anger of the British who took their revenge nearly 239 years ago.